Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 4, 18-23Original Article Article

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS BETWEEN BROAD-SPECTRUM AND NARROW-SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS USED

NEHA KOTEKAR1*, VISHAL PAWAR1, ASHOK GIRI2

1Intern Department of Pharmacy Practice, Shivlingeshwar College of Pharmacy, Latur, Maharashtra, India. 2Clinical Pharmacologist at Apollo Multispeciality Hospital, Latur, Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding author: Neha Kotekar; *Email: kotekarn1@gmail.com

Received: 29 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 22 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The main objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of empiric treatment with broad-spectrum therapy versus narrow-spectrum therapy for a patient hospitalized in the intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital in Latur, Maharashtra, India.

Methods: An institutional-based retrospective observational study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in an intensive care unit from December 2023 to May 2024. The data was collected using a patient profile form and analyzed using the data analysis tool Microsoft Excel. Mann-Whitney U test was used to associate dichotomous variables. A P-value of (0.03) was of significant statistics.

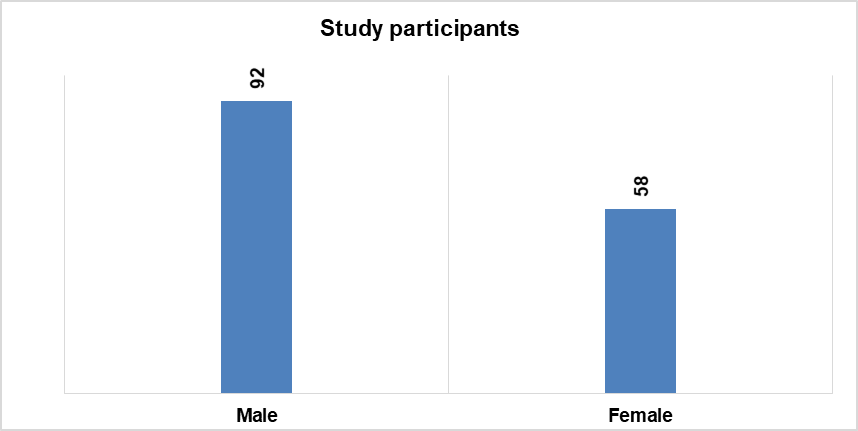

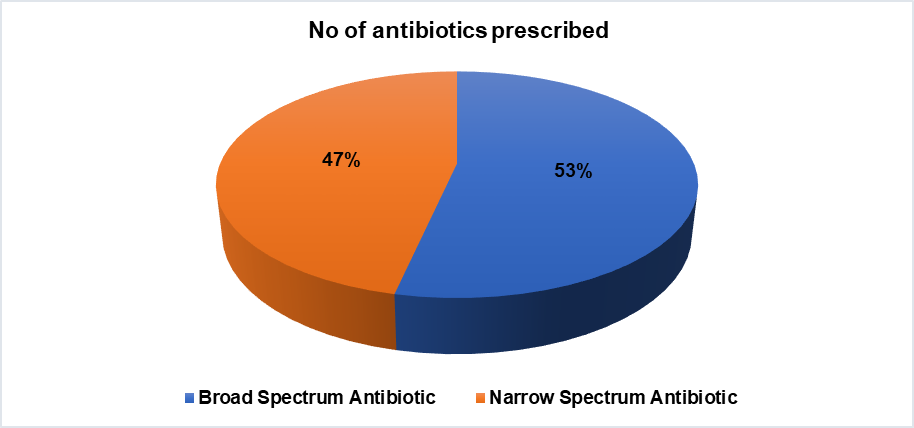

Results: A total of 150 patients were included in the study between December 2023 to May 2024. The majority of them were male 92(61%) and 58 (39%) were female. The majority of the study participants received broad-spectrum antibiotics. Broad-spectrum antibiotics prescribed were (53%) and the remaining (47%) were narrow spectrum. We highlighted the need for an antibiogram in the intensive care unit and also urged the policymakers to introduce antimicrobial stewardship programs and guidelines in healthcare institutes that will help with planning future initiatives among the tertiary care hospitals of India.

Conclusion: There was a difference in the prescribing pattern of antibiotics on their spectrum of activity. Most broad-spectrum antibiotics were prescribed in the hospital to assess early health benefits. Treatment regimens for patients should be selected based on their safety profile and their tendency for antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: Comparative analysis, Anti-microbial resistance, Treatment regimen, Prevalence

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i4.53548 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Antibiotics are the greatest contribution of the 20th century to therapeutics. Their discovery changes the perspective of physician on drugs effect on diseases. Antibiotics either kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria. Antibiotics are substances that are produced by microorganisms and used to kill or inhibit the growth of other microorganisms [1, 2].

Antibiotics are classified based on the spectrum of action into two types – narrow-spectrum and broad-spectrum. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used against a larger number of bacterial infections than narrow-spectrum, which is effective against a small number of bacteria. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are mostly useful when the infection's cause is unknown. The appropriate use of antibiotics is necessary for minimizing the spread of antimicrobial resistance in the world [3–5].

Antibiotic stewardship program balances the benefits and risks of empiric antibiotic prescription, to curtail the emergence of antibiotic resistance and reduce overall health costs. The first important step in this direction is perhaps to collect data on “motives for antibiotic use”. Only a handful of studies have focused on these crucial aspects of the type of antibiotic prescription in the community [6–8].

Many studies were conducted to Investigate and analyze the effectiveness of narrow versus broad-spectrum antibiotics in the treatment of patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. The finding proposed that routine use of penicillin or ampicillin does not contribute to a considerable increase in hospitalization cost despite the increased dosing frequency of the third-generation cephalosporins, such as once daily [9, 10].

A pilot project was conducted in Latur, Maharashtra, India, to quantify the greater use of narrow-spectrum or broad-spectrum antibiotics. The pilot project was conducted by us in Latur, Maharashtra, India, and utilized the methodology as the study that monitored the pattern of prescribing the narrow-spectrum versus the broad spectrum in a community of 150 people [2]. This study was conducted from December 2023 to May 2024. The primary aim of the study was to determine the pattern of prescription and consumption of broad-spectrum versus Narrow-spectrum antibiotics in the Intensive Care Unit. The study involved the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, leading to about 53% as compared to narrow-spectrum antibiotics up to47%out of which antimicrobial resistance is shown by 6% of the people [11–13].

The primary objective and aim of a comparative analysis of broad-and narrow-spectrum antibiotics is to compare the prescribing pattern and the effectiveness of the two types of antibiotics and to understand the outcome of the usage of broad-spectrum antibiotics over narrow-spectrum antibiotics [14, 15].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surveillance of the antibiotics was done by collecting the data from the Intensive Care Unit of the community named Guru Mauli Multi-specialty Hospital located in Latur, Maharashtra, India. The study was done in an intensive Care Unit and 2 different wards of the same community in conjunction with another study i. e. (Prescription pattern of antibiotics for intensive care unit patients) to measure the prescription pattern of broad and narrow-spectrum antibiotics for the patients admitted in Tertiary care Hospital Latur, Maharashtra. Hence, the data was collected by filling out the patient profile form for each individual with an informed consent form (ICF).

Study design

A retrospective, observational study design was conducted whereby prescription and order of all the in-patients from December 2023 to May 2024 were screened and retrieved for further investigation. The data was collected during six months and screening was based on the prescription pattern of antibiotics. The orders for the prescribed broad-spectrum or narrow-spectrum antibiotics on the patient file were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria

All patients anticipated to remain in the ICU for 24 h or more were prospectively evaluated. Patients receiving new antibiotics for confirmed or presumed infection during their stay were included for further analysis.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who are not cooperative and are free to respond are excluded. For patients with a limited duration of stay (less than 24 h), and pregnant women, antibiotics started before admission.

The criteria listed above were excluded from the study as we wanted to minimize the uncertainty.

Study setting

The research was conducted at the In-Patient Department of Guru Mauli multi-specialty Hospital. A Tertiary Care Hospital, private sector was included in the study. It was owned and run by the private owners.

Data collection

At admission, the questionnaire was adapted from previously conducted similar studies. It was divided into two parts the first part consisted of the patient’s socio-demographic data (age, gender, weight, comorbidities, etc.) and the second type consisted of clinical characteristics of the patients (type of admission, type of antibiotic prescribed, duration of stay, total cost of treatment)were recorded. To get the complete details of the antibiotic prescribed in the community; the patient was selected who was willing to cooperate. The data collectors were (Pharm D Interns) who collected antibiotics-prescribed data. The patient was interviewed about chief complaints and the type of diagnosis made by the doctors. A brief history of the patients was taken whether they might have taken any other antibiotics in the past days. Data was collected and recorded directly on the patient profile form and after completion of the patient profile form the data was also entered into the Excel sheet. A pre-designed proforma was used to collect data regarding the name of an antibiotic, the type, the strength, the dose the number of units prescribed by the doctor, and the number of units dispensed or purchased. For the patient who started a new antibiotic prescription, the parameters above were recorded during the treatment course. At the end of follow-up for each episode of a type of antibiotic prescription, suspected and confirmed.

Measurement of sample size

The total number of patient count was headed to be 150, out of which 92 were Male and 58 were female. The distribution was made according to the age groups, highest age group was recorded to be age group between 21 y to 40 y. Data collector’s schedules were randomly prepared for the day and time (two hours) of each visit. During each visit, all the patients receiving any antibiotic were interviewed. Data were collected and recorded at each visit to the hospital. Data was collected from the same facility throughout the study period.

Statistics

The data was collected by interviewing the In-patients, the collected data was maintained in the format of a patient profile form and entered into a data analysis tool by Microsoft Excel 2023 for further analysis. The P value testing was done to find the normality of the prescription of broad and narrow-spectrum antibiotics. Both descriptive and inferential analysis was done for data elaboration. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize the whole data. Mann-Whitney U test was used to associate dichotomous variables. A P-value of (0.03) was of significant statistics. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Statistical software Graph Pad Prism was used for the analysis of data and Microsoft Word and Excel to generate graphs and tables.

Data management

All the data collected was entered into a Data Analysis tool, Microsoft Excel, and filled in a patient profile form for each individual; informed consent was also obtained from each of the individuals; the same was used to analyze the data and find the interpretations of the study.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Guru Mauli Multi-specialty Hospital, Latur. Informed consent was obtained from each one of the individuals who were willing to cooperate, and the facilities involved in the study.

RESULTS

A total of 150 patients were included in the study between December 2023 to May 2024. The majority of them were male 92(61%) and 58 (39%) were female.

Fig. 1: Study participants according to sex

The majority of the study participants received a total number of 216 broad-spectrum antibiotics out of 404, while the remaining received 188 narrow-spectrum antibiotics. Broad-spectrum antibiotics prescribed were (53%) and the remaining (47%) were narrow spectrum. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics target a few types of bacteria; they are more specific and are generally preferable when the effect on other bacteria is limited. Only affect either a kind of bacteria, neither g positive nor g negative.

Fig. 2: Broad and narrow-spectrum antibiotics prescribed

Out of a total number 216 broad-spectrum antibiotics were prescribed. The broad-spectrum antibiotic was chosen widely because of its early health benefits and are often used when the cause of the infection is unknown in the patients admitted to the Intensive Care unit. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are often considered “magic bullets” for treating several life-threatening infectious when the causative pathogen is unknown.

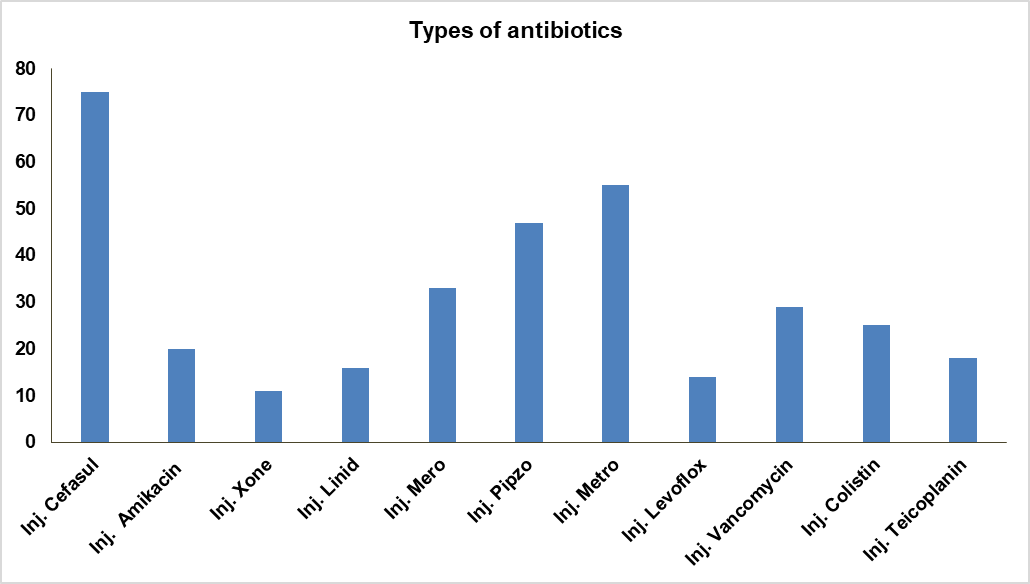

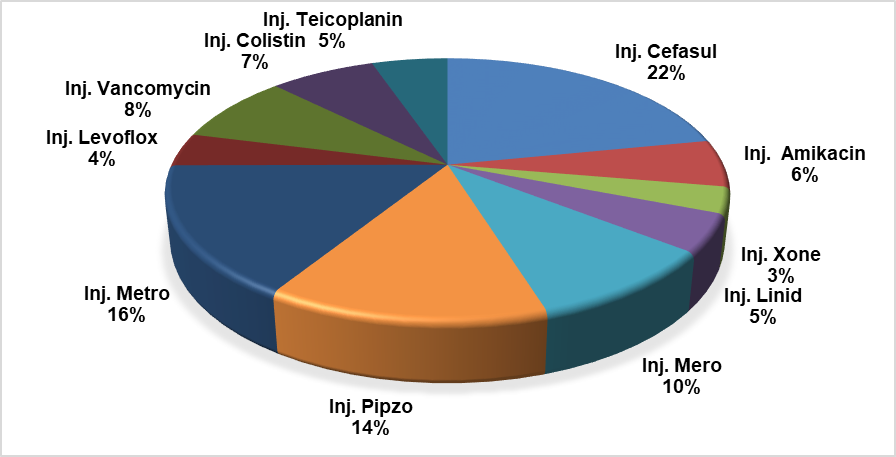

Participants with comorbidities have been recorded in the study, (26) patients with Type 2 diabetes followed by (31) with hypertension, COPD (4), and Hepatitis (2). About half of the participants in the study were exposed to antibiotics before admission. Even several different treatment regimens have been employed for the 150 patients hospitalized with their diagnosis. Cefasul (22%), Metronidazole (16%), Piperacillin (14%), and Amikacin (6%) were the most frequently prescribed medications.

Patients administered broad-spectrum antibiotics had developed antibiotic resistance to the medication, the total count of the patients was (4), remaining (144) were non-resistance patients. Cefasul (75), a most prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic over the past 6 mo in the tertiary care hospital. There was a huge difference between broad and narrow spectrum treatment groups in the main treatment outcomes, on the type of antibiotic therapy administered after admission to the hospital.

Fig. 3: Total number of types of antibiotics prescribed

Sub-group analysis

The sub-group analysis based on the type of antibiotic treatment after hospitalization revealed that patient received either broad-spectrum or narrow-spectrum antibiotics during their hospital stay. The above-enlisted data gives information about the type of antibiotic prescribed to several patients. There was a huge difference between broad and narrow spectrum treatment groups in the main treatment outcome after admission to the hospital.

P value analysis

By investigating the prevalence of broad-spectrum vs narrow-spectrum antibiotic therapy, we found that out of 150 patients, only 47% of the population is prescribed by the narrow-spectrum activity. Broad spectrum antibiotics are prescribed by 53% among which the commonly prescribed antibiotics are cefaperazone+sulbactam, Piperacillin+tazobactam, Meropenem, Amikacin, Levofloxacin. Cefoperazone was the most common empirical antibiotic prescribed. The p-value was calculated to be (*P=0.03). Since the (**P<0.05, *P<0.03), we can reject the Null Hypothesis. This result provides significant evidence in favour of the alternative hypothesis, which states that the p-value is statistically significant. A total of 404 antibiotics were prescribed among 150 patients, (n=216) were transitioned to spectrum antibiotics and (n=188) were narrow-spectrum antibiotics used. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are mostly prescribed over narrow-spectrum antibiotics. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are preferred to access early health benefits in patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

Table 1: Total number of antibiotics

| Commonly prescribed antibiotics antibiotic | No. of prescription of prescriptions |

| Inj. Cefasul | 75 |

| Inj. Amikacin | 20 |

| Inj. Xone | 11 |

| Inj. Linid | 16 |

| Inj. Mero | 33 |

| Inj. Pipzo | 47 |

| Inj. Metro | 55 |

| Inj. Levoflox | 14 |

| Inj. Vancomycin | 29 |

| Inj. Colistin | 25 |

| Inj. Teicoplanin | 18 |

DISCUSSION

This is one of the studies from a developing country that describes, a large, comprehensive surveillance of antibiotic use in an intensive care unit over the past 6 mo. A prescription by a doctor may be taken as a reflection of the doctor’s attitude towards the disease and the role of the drug in the treatment. It provides valuable insight into the nature of the healthcare delivery system of the country. Quality of life can be raised by enhancing standards of medical treatment at all levels. Setting regulations and assessing the quality of health care through performance reviews and audits should become a part of everyday clinical practice. Aiming to look for an appropriate mapping of the antibiotic prescription process in an Indian tertiary care hospital, our study could make several important observations. This one of the studies from a developing country that describes the comprehensive surveillance of antibiotic use in the facility to get a complete picture of the type of antibiotic over 6 mo in an urban community. The quality of antimicrobials and an increased frequency of antimicrobial resistance have emerged as major healthcare [16–18].

Antimicrobial resistance has spread almost to all countries and regions, including India, owing to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics and poor infection control practices. Several factors contribute to the development of AMR and among those irrational prescribing, free availability of antibiotics, and patient-related factors are commonly highlighted in the study. In one study from Europe, it is concluded that antibiotics are highly prescribed in tertiary care as well as in primary care and there is a need for urgent action to improve the prescription practices, starting from the integration of WHO treatment recommendations and the awareness classification into national guidelines. Therefore, the primary objective of the current study was to assess the prescribing practices of physicians while choosing the type of spectrum of antibiotics [19].

The present study fills the gap, and the methodology used can be utilized in any developing country to collect data on in-patient antibiotic usage [20]. In our study mostly broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed without establishing the targeted drug therapy. By investigating the prevalence of broad-spectrum vs narrow-spectrum antibiotic therapy, we found that out of 150 patients, only 47% of the population is prescribed by the narrow-spectrum activity. Broad spectrum antibiotics are prescribed by 53% among which the commonly prescribed antibiotics are cefaperazone+sulbactam, Piperacillin+tazobactam, Meropenem, Amikacin, Levofloxacin. Cefoperazone was the most common empirical antibiotic prescribed, with 22% followed by Inj. Piperacillin and tazobactam 14% to ICU patients.

Empirical use of broad-spectrum antibiotics had been observed. To avoid these, guidelines recommended switching intravenous to oral antibiotics once clinical stability is achieved, as this strategy decreases the length of stay without sacrificing patient safety [21].

The objective was to measure accurately population exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, but rather to measure trends in use as part of a surveillance system. The most important strength of the study is that it clearly shows that it is possible to collect useful data for antibiotic use in an intensive care unit and all facilities from wherever it is prescribed, at the individual patient level in resource-constrained settings. The study has some inherent weaknesses. Firstly, it was conducted in only one residential locality of one urban area, so generalization should be done with caution for the rest of Latur and cannot be done for other areas of India [22–24].

Fig. 4: Broad versus narrow-spectrum antibiotics

The difference in rates of broad versus narrow-spectrum antibiotics prescribed could be explained by different natures of the denominator used in these studies as well as the study setting, data collection period, and the difference in types and availability of antibiotics. Additionally, patient’s expectations and demands of an antibiotic during the consultation are also frequently reported in the literature as a major reason for inappropriate antibiotic prescribing [25, 26].

LIMITATIONS

In a single-centered study, the generalizability of the findings is always an issue. Our study was conducted at only one tertiary care hospital; therefore, it might not capture the variations in antibiotics prescribing practices on their spectrum of activity across different institutions or regions. We looked at drug use patterns over 6 mo only. Reviewing of the patient records, important patient information may be missing due to poor documentation, and/or recording error/bias. The study was devoid of making a temporal relationship (cause and effect relationship) between the outcome variable (improvement of signs and symptoms) and the different independent variables.

CONCLUSION

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are mostly used, particularly for minor infections, misused for self-limiting viral infections and narrow-spectrum antibiotics are underused due to financial crises. Extensive surveillance programs have been used to study patterns of antibiotic resistance and use in developed countries. These systems have made it possible to stimulate the implementation of nationwide interventions to improve antibiotic use. The prescribing pattern of the antibiotics for the management of the patient in the hospital was inconsistent with current guidelines. Quality use of antibiotics can help prevent the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. A better understanding of appropriate antibiotic prescribing must be fostered among prescribers. Strict adherence to guidelines must be ensured and provide the rationale and target drug therapy for broad-spectrum antibiotics. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are mostly in critically ill ICU patients to access early health benefits. The methodology can collect useful data that reveal the usage and pattern of antibiotic use in the community. Treatment regimens for patients should be selected based on their safety profile and their tendency for antibiotic resistance. We highlighted the need for antibiograms in the intensive care unit and also urged the policymakers to introduce antimicrobial stewardship programs and guidelines in healthcare institutes that will help with planning future initiatives among the tertiary care hospitals of India.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We sincerely acknowledge the support of the B. Sc. Nursing Students and the RMO of the Guru Mauli Multi-speciality Hospital, Latur in the data collection process. Sincere thanks and regards to Dr. Sunita Patil for supervising the data collection process. Thanks to the Department, Principal, and Teaching Facilities of Shivlingeshwar College of Pharmacy, Almala, Latur.

FUNDING

The author declares that they did not have any funding source or grant to support the research work.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, visualization, Manuscript writing, and original draft: Neha Kotekar

Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and validation: Vishal Pawar

Investigation, data analysis, and data interpretations: Dr. Ashok Giri

Final approval of manuscript: Neha Kotekar, Vishal Pawar, Dr. Ashok Giri

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in the paper.

REFERENCES

Borah M, Khanikar D, Chakraborty SS, Charkraborty A, Devi D, Dudhraj V, Bahl A. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial consumption in a Tertiary Care Hospital of North East India. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024 Dec 1;16(12):31–6. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i12.52442

Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):742-50. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7, PMID 25022435.

Bhat P, Bhumbla U, Kaur J. War in the middle ear: microbiology of chronic suppurative otitis media with special reference to anaerobes and its antimicrobial susceptibility pattern: optimizing antimicrobial therapy in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Rural India. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2025 Jan 1;17(1):12-20. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i1.52692.

Williams A, Mathai AS, Phillips AS. Antibiotic prescription patterns at admission into a tertiary level intensive care unit in Northern India. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011 Oct;3(4):531-6. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90108, PMID 22219587.

Hashmi H, Sasoli NA, Sadiq A, Raziq A, Batool F, Raza S. Prescribing patterns for upper respiratory tract infections: a prescription-review of primary care practice in Quetta, Pakistan and the implications. Front Public Health. 2021 Nov 19;9:787933. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.787933, PMID 34869195.

Kotwani A, Holloway K. Trends in antibiotic use among outpatients in New Delhi, India. BMC Infect Dis. 2011 Apr 20;11:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-99, PMID 21507212.

Prost M, Rockner ME, Vasconcelos MK, Windolf J, Konieczny MR. Outcome of targeted vs empiric antibiotic therapy in the treatment of spondylodiscitis: a retrospective analysis of 201 patients. Int J Spine Surg. 2023;17(4):607-14. doi: 10.14444/8482, PMID 37460238.

Ghosh S, Salhotra R, Singh A, Lyall A, Arora G, Kumar N. New antibiotic prescription pattern in critically ill patients (‘ant-critic’): prospective observational study from an Indian Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022 Dec 1;26(12):1275-84. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24366, PMID 36755637.

Driessen RG, Groven RV, Van Koll J, Oudhuis GJ, Posthouwer D, Van der Horst IC. Appropriateness of empirical antibiotic therapy and added value of adjunctive gentamicin in patients with septic shock: a prospective cohort study in the ICU. Infect Dis (Lond). 2021;53(11):830-8. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1942543, PMID 34156899.

BG D, D CA, NN M, HN P. Study of prescribing pattern of antimicrobial agents in medicine intensive care unit of a Tertiary Care Hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2020 Mar 20:136-40.

Mettler J, Simcock M, Sendi P, Widmer AF, Bingisser R, Battegay M. Empirical use of antibiotics and adjustment of empirical antibiotic therapies in a university hospital: a prospective observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2007 Mar 26;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-21, PMID 17386104.

Alharthi N, Kenawy G, Eldalo A. Antibiotics’ prescribing pattern in intensive care unit in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Sci. 2019;8(1):47. doi: 10.4103/sjhs.sjhs_12_19.

Ghafur A. The chennai declaration: a solution to the antimicrobial resistance problem in the Indian subcontinent. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1190. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1224, PMID 23307765.

Hutchings MI, Truman AW, Wilkinson B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;51:72-80. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008, PMID 31733401.

Zhu Y, Huang WE, Yang Q. Clinical perspective of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:735-46. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S345574, PMID 35264857.

Ganguly NK. Professor of biotechnology D, Nair Kapoor A, Joshi PC, Joglekar S, Arora NK. India: Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (GARP. India) National Working Group (NWG) GARP-India staff; 2008.

WHO library cataloging-in-publication data global action plan on antimicrobial resistance; 2015.

Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Robinson TP. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015 May 5;112(18):5649-54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112, PMID 25792457.

Jain S, Das Chugh T. Antimicrobial resistance among blood culture isolates of Salmonella enterica in New Delhi. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(11):788-95. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3030, PMID 24240035.

Antibiotic Resistance: multi-country public awareness survey; 2015.

Adhikari L. High-level aminoglycoside resistance and reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in nosocomial enterococci. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2(3):231-5. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.68534, PMID 20927283.

Mehta A, Rosenthal VD, Mehta Y, Chakravarthy M, Todi SK, Sen N. Device-associated nosocomial infection rates in intensive care units of seven Indian cities. Findings of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC). J Hosp Infect. 2007 Oct;67(2):168-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.07.008, PMID 17905477.

D’Souza N, Rodrigues C, Mehta A. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus with emergence of epidemic clones of sequence type (ST) 22 and ST 772 in Mumbai, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 May;48(5):1806-11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01867-09, PMID 20351212.

Blair JM, Webber MA, Baylay AJ, Ogbolu DO, Piddock LJ. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(1):42-51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3380, PMID 25435309.

Dutta S, Haque M. COVID-19: questions of antimicrobial resistance. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2021;20(2):221-7. doi: 10.3329/bjms.v20i2.51527.

Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health. 2015;109(7):309-18. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030, PMID 26343252.