Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 3, 36-44Original Article

BIOCARRIERS AMPLIFYING ANTI-AGING: CARNOSINE LOADED NANOGEL ON D-GALACTOSE INDUCED SKIN AGING IN RAT MODEL

GOWTHAM SUNDARRAJAN*, ARIHARASIVAKUMAR G., PRIYANKA S.

1,2Department of Pharmacology, Kmch College of Pharmacy, Tamil Nadu, India. 3Department of Pharmaceutics, Senghundhar College of Pharmacy, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Gowtham Sundarrajan; *Email: gowthamkavur5@gmail.com

Received: 02 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 06 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of biocarriers in amplifying the anti-aging effects of Carnosine-Loaded Nanogel (CAR-HS) on D-Galactose (D-gal) induced skin aging in sprague dawley rats.

Methods: Thirty-four Sprague Dawley rats were divided into six groups: Group I (healthy control, no treatment), Group II (D-GAL positive control), Groups III to V (treated with carnosine-loaded gels), and Group VI (blank hydrosomes (HSblank)). Evaluation parameters included drug content, encapsulation efficiency, vesicle size, zeta potential, polydispersity index (PDI), in vitro drug release, antioxidant markers, histopathology, and hematological analysis.

Results: Carnosine Hydrosomes (CAR-HS) demonstrated significant de-aging effects. Antioxidant marker levels (Superoxide Dismutase (SOD): 56.8±3.4 U/mg, Catalase (CAT): 85.2±4.1 U/mg, GSH: 12.6±0.8 nmol/mg, MDA: 2.1±0.2 nmol/mg) showed significant improvements (p<0.05) compared to the positive control group (SOD: 32.3±2.7 U/mg, CAT: 49.5±3.2 U/mg, Glutathione (GSH): 6.8±0.6 nmol/mg, Malondialdehyde (MDA): 4.7±0.3 nmol/mg). Histopathological analysis revealed normal epidermal structures and minimal immune cell infiltration in the hydrosomes group, while the positive control exhibited extensive damage. Hematological analysis indicated improved Red Blood Cell (RBC) (6.7±0.4 million/µl) and Hemoglobin (Hb) levels (13.5±0.7 g/dl) in the hydrosomes group compared to the positive control (RBC: 4.8±0.3 million/µl, Hb: 9.2±0.5 g/dl). Spleen histology supported these findings, showing reduced age-related changes.

Conclusion: The present study revealed that anti-aging of CAR-HS holds significant potential for tissue repair, effectively reducing oxidative stress and associated inflammation, likely through mechanisms involving cellular-level damage repair.

Keywords: Skin aging, Nanogel, Biocarriers, Carnosine peptide, Hydrosomes, Cosmeceuticals

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i3.53570 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Skin aging is a complex biological process that extends beyond the visible laxity of the integument. It encompasses immunosenescence, dysbiosis, increased susceptibility to cutaneous malignancies, impaired wound healing, and stem cell senescence. These interconnected cellular and molecular pathways illustrate both the pathological aging phenotype and dysfunction within the skin, shedding light on how aging impacts extracutaneous tissues throughout the body. The classification of skin aging as a disease is complicated by historical, sociocultural, and diagnostic considerations, much like the evolution of osteoporosis from being viewed as a natural aging consequence to a treatable condition [1]. While intrinsic biological decline remains a primary driver of skin aging, environmental factors also significantly contribute, impacting overall organismal health and well-being. Lifelong exposure to external insults accelerates skin aging, reflecting a broader aging process that manifests through genetic, epigenetic, microbiome, and proteomic changes over time. Differentiating between chronological and environmentally-induced skin aging remains challenging, highlighting the multifactorial nature of this phenomenon [2-6].

The International Anti-Aging Systems recognizes several "Theories of Aging," with five being particularly prominent in personal care and cosmetic sciences [7]. The Wear and Tear Theory, proposed by Dr. August Weissman in 1882, attributes aging to the cumulative damage from toxins, radiation, and Ultraviolet (UV) light, surpassing the body's repair capacity and leading to visible signs like wrinkles [8]. Dr. Johan Bjorksten's Glycosylation Theory (1941) postulates that aging involves protein and molecule cross-linking, which reduces flexibility and functionality, contributing to stiff, yellowish skin and wrinkles [9]. The Neuroendocrine Theory by Dr. Vladimir Dilman (1954) suggests that hormonal imbalances due to hypothalamic dysfunction accelerate muscle breakdown and collagen loss, resulting in aged skin. Dr. Denham Harman's Free Radical Theory (1956) identifies highly reactive free radicals as culprits in cellular damage, disrupting Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) and protein synthesis, particularly affecting collagen and elastin, and leading to wrinkles and diminished self-repair [10]. Lastly, the Telomere Theory, proposed by Alexei Olovnikov and John Watson in 1972, highlights telomere shortening with each cell division, eventually halting cell renewal and contributing to aging and cellular senescence [11]. The incorporation of active constituents into protective delivery systems capable of mobilizing, dispersing, amplifying efficacy, and targeting biological barriers remains a pivotal strategy in the cosmetic industry. Encapsulation enhances ingredient performance by facilitating biological penetration, prolonging active duration, improving solubility, mitigating adverse effects, and concentrating actives at specific targets. Over the past three decades, encapsulation technologies have revolutionized drug delivery, with nanotechnology emerging as a key driver. Nano-sized systems, owing to their large surface area, are particularly suitable for skin applications, although they raise concerns regarding toxicological and environmental implications. Various nano-formulations used in cosmetics include nano-gels, nano-emulsions, nano-suspensions, nano-spheres, nano-tubes, nano-powders, nano-capsules, lipid nano-particles, and dendrimers [12-14]. In the 1960s, Bangham et al. demonstrated that dispersing natural phospholipids in aqueous solutions leads to the formation of "enclosed vesicle structures" resembling cellular morphology. Since 1975, vesicles have been synthesized from surfactants, with Mezei and Gulasekharam pioneering the study of liposome efficacy in skincare [15]. By 1986, the first commercial liposome-based products were introduced, accompanied by nonionic surfactant-based niosomes [16]. These vesicles, composed of concentric lipid bilayers interspersed with aqueous compartments, exhibit transcutaneous penetration based on lipid fluidity and negative charge. Transfersomes, developed in the 1990s, are more flexible than traditional liposomes due to their composition of fatty acids and surfactants, enabling rapid penetration through the stratum corneum via osmotic gradients. Ethosomes, another innovation, consist of flexible phospholipid vesicles capable of delivering diverse molecules to deep skin layers or systemically [17]. Hydrosomes, a water-based form of liposomes, enhance the delivery of water-soluble actives, improving stability, bioavailability, and moisture retention. This study aims to evaluate the topical effects of CAR-HS as an anti-aging nano-cosmeceutical gel in D-gal-induced skin aging in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Carnosine was procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium alginate was sourced from Isochem Laboratories. Carbopol was purchased from Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., while soy lecithin was obtained from Ashrip Enterprises. All materials required for the formulation were acquired within India.

Preparation of carnosine hydrosomes

CAR-HS were prepared using an ultrasonic encapsulation technique. Briefly, carnosine and sodium alginate were dissolved in an aqueous phase and subsequently incorporated into a soy lecithin dispersion. The mixture underwent overnight hydration followed by ultrasonic irradiation to encapsulate the carnosine. HSblank were produced using the same method but omitting carnosine. The final formulations were sealed and refrigerated, and CAR-HS were subsequently optimized for drug content and encapsulation efficiency. This technique offers the advantages of simplicity, and cost-effectiveness and avoids the use of organic solvents, making it suitable for pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical applications [18].

Preparation of carnosine conventional gel

A Carbopol-Based Control Gel (CAR-GEL) containing carnosine was prepared via a solvent-based gelation method. Carbopol 940 was dispersed in an aqueous carnosine solution using magnetic stirring at room temperature. Subsequent addition of triethanolamine neutralized the Carbopol and adjusted the pH to 5.5, promoting gel formation and maintaining a favourable skin microbiome environment. Finally, bath sonication was performed to eliminate air bubbles to ensure formulation homogeneity [19].

In vitro characteristics

pH measurement

The in-situ pH of the gel formulation was determined using a digital pH meter. The glass electrode was fully immersed to ensure complete contact with the gel system, and the measurement was performed in triplicate to enhance data reliability. The final reported value represents the average of the three individual pH readings [20].

Drug content and encapsulation efficiency

CAR-HS containing a known amount of drug was dissolved in a phosphate buffer solution with a pH of 5.5 to create 10 micrograms per millilitre stock solution. The resulting solution's absorbance was then measured using a UV spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu corporation, Japan) at the wavelength (273 nm) where the drug exhibits its maximum absorbance.

To assess the entrapment efficiency of carnosine within the nanogels, a centrifugation process was employed. Aliquots of 2.5 ml from the CAR-HS formulation were subjected to centrifugation for 20 min at 3000 rpm at room temperature within a standard Eppendorf tube. The supernatant was then analysed using UV-spectrophotometry at a wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) of 273 nm to quantify the amount of free carnosine. This indirect measurement allows for the determination of the amount of carnosine entrapped within the nanocarriers [21].

Vehicle size, zeta potential and polydispersity index

The physicochemical properties of Carnosine hydrosomes were assessed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique using Zeta sizer Nano ZS. (Malvern, Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK). The sample was sonicated (5 min) then dilution was performed for the developed formulation with freshly filtered distilled water. DLS was employed to assess the PDI of CAR-HS, a crucial metric for characterizing the uniformity of the drug carrier system. PDI is a dimensionless value that reflects the size distribution of particles within the sample. PDI values closer to 0.1 indicate a monodisperse system, while if it is above 0.3 then it shows PDI of the nanocarriers [22].

Field emission – scanning electron microscopy

The morphology of CAR-HS and HSblank was investigated using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). To prepare the samples for analysis, a thin film was generated from each formulation. This involved depositing a small amount of each formulation onto a microscope slide and subjecting it to vacuum drying to remove the solvent without altering the structural integrity of the hydrosomes. This process creates a film suitable for FE-SEM analysis, allowing for visualization of the morphology of the CAR-HS and HSblank [23].

In vitro drug diffusion study

A comparative in vitro diffusion study was conducted to assess the release characteristics of CAR-HS versus a CAR-GEL. The beaker method with magnetic stirring was employed. Briefly, one millilitre samples of each formulation containing equivalent amounts of carnosine (2% w/v) were placed in a donor cylinder sealed with a dialysis membrane. This donor compartment was then immersed in 70 ml of release medium (phosphate-buffered saline, pH 5.5) and continuously stirred at 10 rpm. To maintain sink conditions, mimicking absorption into the bloodstream, 1 ml aliquots were withdrawn from the release medium at predetermined time points (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h) and replaced with fresh medium. The concentration of carnosine released in the withdrawn samples was then quantified spectrophotometrically at its maximum absorbance wavelength (λmax 273 nm). This approach allowed for the determination of the diffusion profiles of carnosine from both the hydrosomes and the gel formulation [24].

In vivo characteristics

Animals

Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Biogen laboratory animal facility, Bengaluru, Reg. no. KMCRET/ReRc/M. Pharm/69/2023. Rats were kept in separate cages (6 animals per cage) and housed with husk as a bedding material under normal room temperature (25±20 °C), 24 h light and dark cycle as well as constant relative humidity (55±5%) throughout the experimental period according to Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA) guidelines.

Induction of skin aging on rats

Rats were subcutaneously injected with D-gal at a dose of 1000 mg/kg for a period of six weeks to induce skin aging. Subsequently, skin, spleen, and blood samples were collected from the positive control group at the study endpoint. Treatment: Following D-gal administration to induce a relevant model, rats underwent a six-week topical treatment regimen on their shaved dorsal area. Treatment groups received CAR-GEL, 1% and 2% CAR-HS, and HSblank, respectively. Subsequently, blood samples, skin tissues, and spleens were collected for in vivo validation of the treatment effects [25].

Experimental groups

Group I (Negative Control): Rats were untreated and maintained as a healthy control group.

Group II (Positive Control): Rats received subcutaneous injections of D-gal for 6 w to induce skin aging.

Group III (D-gal+2% CAR-GEL): Following 6 w of D-gal administration, 2% CAR-GEL was topically applied to the dorsal skin of rats for an additional 6 w.

Group IV (D-gal+1% CAR-HS): Following 6 w of D-gal administration, 1% CAR-HS was topically applied to the dorsal skin of rats for an additional 6 w.

Group V (D-gal+2% CAR-HS): Following 6 w of D-gal administration, 2% CAR-HS was topically applied to the dorsal skin of rats for an additional 6 w.

Group VI (D-gal+HSblank): Following 6 w of D-gal administration, HSblank was topically applied to the dorsal skin of rats for an additional 6 w [26].

Biochemical analysis

In a pilot study, the antioxidant potential of CAR-HS was evaluated against CAR-GEL and HSblank at the conclusion. This assessment employed enzymatic antioxidant markers, including SOD and CAT, alongside non-enzymatic antioxidant markers, such as GSH and MDA [26].

Haematological assessment

Evaluating the complete blood count (CBC) in this study serves to assess the systemic health of the animals, ensuring that neither the D-gal-induced aging model nor the CAR-HS treatment causes adverse effects or toxicity. CBC provides critical insights into inflammation and oxidative stress, both key contributors to aging, by analysing parameters such as white blood cell counts (WBC), leucocytes, red blood cell counts (RBC) and haemoglobin (Hb). It helps validate the D-gal model by detecting aging-related systemic changes and demonstrates the potential protective effects of carnosine hydrosomes by normalizing or improving CBC abnormalities. Additionally, CBC results can reveal immunomodulatory effects and systemic anti-inflammatory benefits of carnosine hydrosomes, highlighting their efficacy in mitigating aging-related oxidative damage beyond localized skin treatment.

Histological assessment

Histopathology of skin

In a dermal assessment for signs of reversed aging, histopathological evaluation serves as the gold standard diagnostic technique. This method involves collecting a skin sample via biopsy, fixation, sectioning, staining with specific dyes, and microscopic examination to identify any pathological deviations indicative of age reversal.

Histopathology of spleen

In the context of D-gal-induced aging, histopathological evaluation of the spleen can reveal age-related changes like lymphocyte depletion, macrophage activation, extracellular matrix expansion, hemosiderosis, potential amyloid deposition, and megakaryocytes. Either of these findings can help assess the impact of D-gal on the spleen's structure and cellularity, potentially supporting the thesis of D-gal-induced aging.

Collection of materials

In a comparative analysis, dorsolateral skin specimens were obtained from areas exhibiting visible signs of senescence alongside control samples of unaffected tissue. As well as spleens were collected in individual groups. Fixation: Kept the tissue in fixative for 24-48 h at room temperature The fixation was useful in the following ways: a) Serves to harden the tissues by coagulating the cell protein; b) Prevents autolysis; c) Preserves the structure of the tissue; d) Prevents shrinkage and Common Fixatives: 10% Formalin.

Haematoxylin and eosin method of staining

The tissue section underwent deparaffinization in xylene for 5-10 min, followed by washes in absolute alcohol and tap water. Haematoxylin staining was performed for 3-4 min, followed by another tap water wash. The section was then counterstained with eosin for 15-30 seconds until a light pink colour was observed. After rinsing with tap water, the section was dehydrated through a series of alcohols, cleared with xylene, and mounted using Canada balsam or DPX (Distyrene Plasticizer Xylene) mounting medium. The slide was allowed to dry completely, ensuring the absence of air bubbles.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were manifested as the mean of triplicate experiments±SD. Statistical analyses of the data were conducted using a one-way ANOVA test then the Tukey test for multiple comparisons was conducted. The GraphPad Prism® (Version 5.0) software was used (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). The differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

This study explored the development and application of CAR-HS-based nanoplatforms as an innovative topical nanogel designed to enhance the diffusion of carnosine into the skin layers for anti-aging therapy.

Development of blank and carnosine hydrosomes

2% (w/v) CAR-HS were prepared by dissolving 0.5 g sodium alginate and 0.2 g carnosine in 10 ml of distilled water, followed by stirring for 5 h at room temperature. This drug-polymer solution was combined with 1.0 g of soy lecithin and 1 ml of glycerine then allowed to hydrate overnight. The mixture was stirred for an additional 5 h and subjected to sonication for 30 min using a high-intensity ultrasonic probe sonicator at room temperature. HSblank were prepared using the same method without carnosine. Both formulations were sealed and stored overnight in a refrigerator for stabilization. For comparison, a CAR-GEL containing 2% carnosine was formulated. Carbopol 940 (0.5 g) was dispersed in an aqueous carnosine solution (2%) at room temperature, neutralized with triethanolamine to adjust the pH to 5.5, and sonicated in a bath sonicator to remove air bubbles.

pH of the gel formulation

The pH of the gel formulation determined at room temperature and was found to be 5.5.

Physiochemical properties measurements vesicle size, zeta potential and polydispersity index

The 2% CAR-HS formulation was analyzed for vesicle size, zeta potential, and PDI. The average vesicle size was found to be 544.1 nm. The zeta potential was measured at-29.3 mV, indicating a strong negative surface charge. Vesicle size distribution analysis revealed a PDI of 0.363, reflecting a moderately uniform population of nanocarriers [26].

Drug contend and encapsulation efficiency

Both 1% CAR-HS and 2% CAR-HS formulations demonstrated promising drug delivery characteristics. The drug content ranged from 71.4% to 80.30%, while encapsulation efficiency was between 69.33% and 77.89%, indicating effective loading of carnosine within the biocarriers [27].

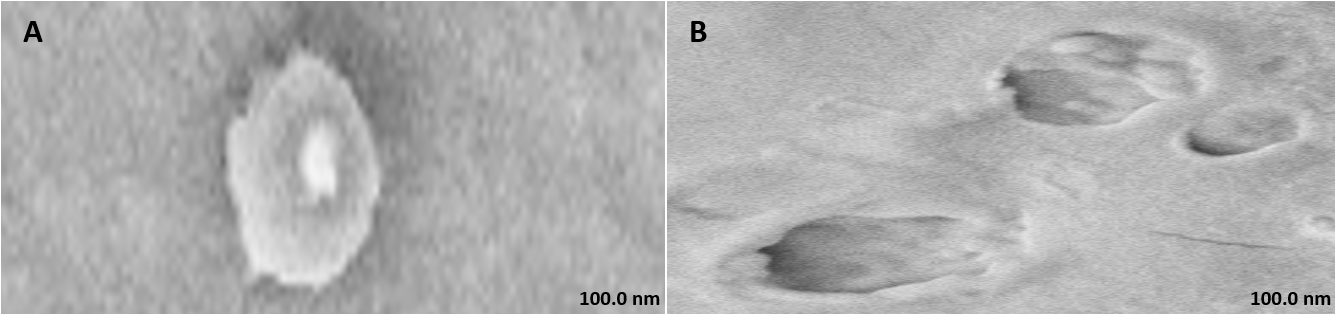

Field emission – scanning electron microscopy

FE-SEM analysis revealed characteristically dispersed, spherical vesicles for both CAR-HS and HSblank formulations. The CAR-HS micrographs displayed a distinct "shady coat and core" morphology [28].

Fig. 1: FE-SEM of (A) Carnosine hydrosomes and (B) HS blank (magnification: 5.00 K X and 10.00 K X respectively)

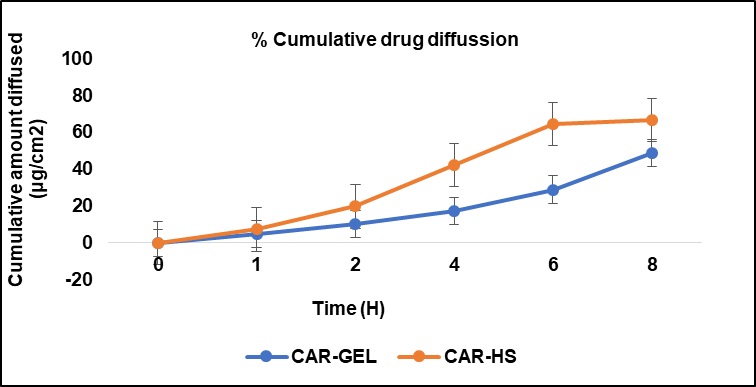

In vitro drug diffusion study

The in vitro drug diffusion study showed that both CAR-GEL and CAR-HS exhibited an increase in percentage cumulative drug diffusion over an 8-hour period, indicating sustained release of carnosine from both formulations. CAR-HS demonstrated a faster initial release of carnosine compared to CAR-GEL, as indicated by a steeper slope in the diffusion curve during the first 2 h. After this initial burst phase, CAR-GEL displayed a slower and more gradual release of carnosine compared to CAR-HS [29].

Fig. 2: In vitro release profile of CAR-GEL and Carnosine hydrosomes with same concentrations (2% w/v) in phosphate buffer saline (pH 5.5). Results are represented as mean±SD, n = 3

In vivo studies

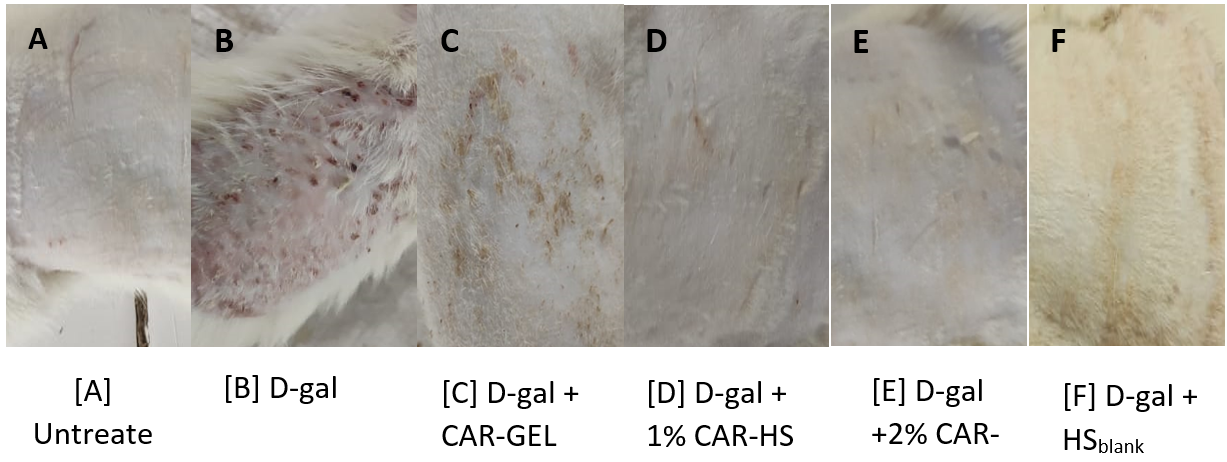

Aging induction and treatment

Following topical application, the dorsal skin of rats was evaluated visually. The negative control group exhibited an unimpaired and smooth epidermal surface, while the positive control group showed signs of aging, including edema (localized fluid accumulation), erythema (redness), and epidermal thickening with prominent scars after D-gal induction. CAR-GEL treatment resulted in minimal scar formation, and HSblank application displayed a potential de-aging effect. Notably, CAR-HS treatment led to visibly intact and wrinkle-free skin.

Fig. 3: Images of the dorsal skin of rats: (A) Untreated group; (B) D-gal-administered group after 6 w; (C) D-gal-induced group treated topically with 0.2 g CAR-GEL for 6 w; (D) D-GAL-induced group treated topically with 1% CAR-HS for 6 w; (E) D-gal-induced group treated topically with 2% CAR-HS for 6 w; (F) D-gal-induced group treated topically with HSblank for 6 w

Biochemical analysis

Anti-oxidant markers

D-gal administration (positive control) resulted in a statistically significant decrease in antioxidant marker levels, including GSH, SOD, and CAT, and an increase in MDA levels compared to the negative control group. Topical application of CAR-GEL (Group III) led to significant improvements in antioxidant markers, as revealed by ANOVA analysis, with increased CAT, SOD, and GSH levels and decreased MDA levels compared to the positive control group. HSblank administration also showed improvements in CAT, SOD, and GSH levels and reduced MDA levels compared to the positive control group, indicating intrinsic antioxidant activity of the hydrosomes.

The CAR-HS group demonstrated a synergistic effect, showing significantly higher CAT, SOD, and GSH levels and lower MDA levels compared to both CAR-GEL and HSblank formulations. Compared to CAR-GEL, CAR-HS exhibited greater improvement in all antioxidant markers, substantiating their enhanced antioxidant potential [30].

Haematological assessment

The study investigated the levels of RBC, Hb, WBC, and lymphocytes across different groups, including a positive control group. The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in mean RBC and Hb levels (p<0.001) and in WBC and lymphocyte levels (p<0.01) between at least one of the experimental groups and the positive control group.

Histopathological examination

Histopathology of skin

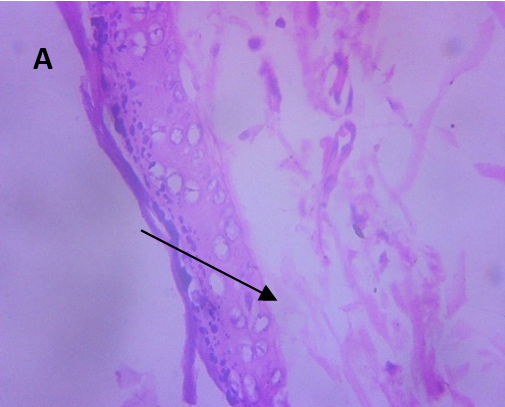

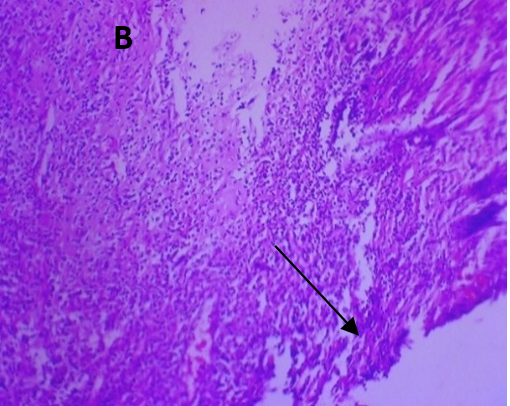

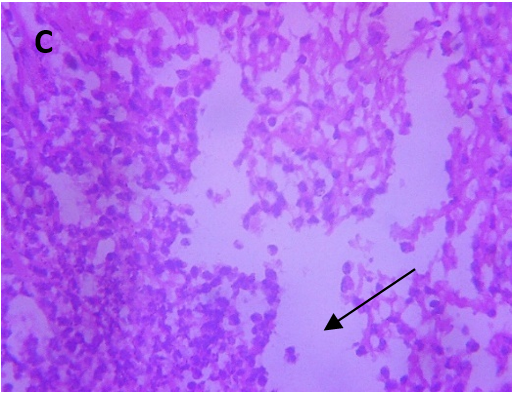

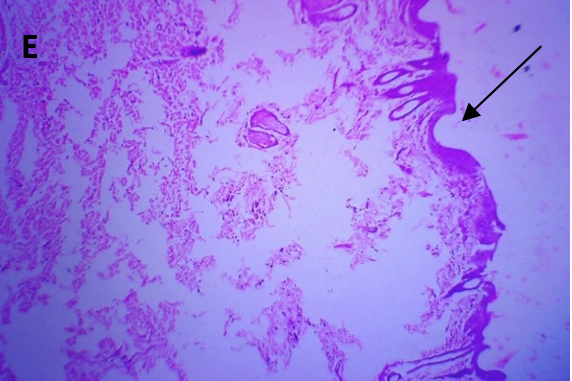

Microscopic examination of the skin revealed healthy tissue architecture in the control group (A), characterized by an intact epidermis and minimal immune cell infiltration. The positive control group (B) exhibited significant tissue damage, with females showing localized areas of focal surface ulceration, dense immune cell infiltration, and thin-walled congested blood vessels in the dermis. The positive control group displayed scattered immune cell infiltration, mild dermal edema, and thickening of the epidermis (exuberant epidermis). The CAR-GEL groups (C) demonstrated reduced inflammatory cell infiltrates compared to the positive control group. Notably, all CAR-HS-treated groups (D) showed increased collagen fiber deposition (fibro-collagenous stroma) in the dermis, indicating tissue repair. HSblank treated (E) samples exhibited a reduction in epidermal thickness and fewer signs of abnormal immune cell infiltration or congested blood vessels compared to the positive control group.

Fig. 4: The antioxidant activities of (A) SOD, (B) CAT, (C) GSH, and (D) MDA were evaluated and presented as mean±SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test with Prism 5.0 software. Statistical significance was set at ***P<0.001 when compared to both positive and negative control groups and ^^P<0.01 when compared to the negative control group

Fig. 5: The levels of RBC, Hb, WBC, and lymphocytes were assessed and expressed as Mean±SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test with Prism 5.0 software. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ***P<0.001 for comparisons against the positive control group for RBC, Hb, and WBC levels; **P<0.01 for lymphocyte levels compared to the positive control group

Fig. 6: Micrographs demonstrating histopathological changes in groups under investigation using light microscopy and determination of the mean morphometric analysis of skin

Histopathology of spleen

Microscopic examination of the spleen in negative control, carnosine-treated (A), and HSblank treated (B) groups displayed normal histoarchitecture, including intact red and white pulp. The white pulp exhibited lymphoid aggregates forming germinal centres, and the penicillar arteries appeared normal without evidence of toxic changes. In the D-gal-induced (positive control) group (C, D), mild stromal congestion was observed, suggesting increased blood flow within the spleen. Additionally, the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages was noted, indicating macrophages containing hemosiderin, a byproduct of red blood cell breakdown.

Fig. 7: Micrographs demonstrating histopathological changes in groups under investigation using light microscopy and determination of the mean morphometric analysis of spleen

DISCUSSION

The preparation of CAR-HS utilized a phospholipid-based approach that supports efficient encapsulation and stability of carnosine, aided by sodium alginate and soy lecithin [31], which provide structural integrity and hydration properties. The sonication step likely played a significant role in reducing particle size and achieving uniform dispersion of the hydrosomes. Similarly, the CAR-GEL formulation demonstrated the importance of pH adjustment (pH 5.5) to maintain skin microbiome equilibrium, with triethanolamine serving as a neutralizing agent to ensure proper gel consistency. These methods underscore the importance of specific formulation strategies in tailoring drug delivery systems for topical applications.

The vesicle size of 544.1 nm suggests that the 2% CAR-HS formulation falls within an appropriate range for topical drug delivery systems, allowing for effective skin penetration. Comparable studies have demonstrated that nanocarriers with vesicle sizes under 600 nm achieve improved permeation through the stratum corneum [32]. The zeta potential of −29.3 mV indicates a stable formulation, as a zeta potential within ±30 mV provides sufficient repulsive force to prevent aggregation, ensuring the stability of the nanocarrier system. The PDI value of 0.363, indicative of a moderately uniform size distribution, is acceptable for many drug delivery applications. However, a lower PDI value would further enhance consistency in drug loading and delivery, as observed in optimized formulations for other topical antioxidants [33].

The observed drug content and encapsulation efficiency suggest that the employed phospholipid matrix plays a critical role in achieving these favourable outcomes. The matrix likely provides a biocompatible and hydrophilic environment that facilitates efficient drug incorporation and enhances the stability of carnosine within the nanovesicles. Similar findings have been reported in the development of phospholipid-based nanocarriers for antioxidants like resveratrol, which showed improved encapsulation efficiency and stability [34]. These characteristics highlight the potential of CAR-HS formulations as efficient carriers for topical drug delivery.

The "shady coat and core" morphology observed in the CAR-HS micrographs likely indicates successful carnosine incorporation within the hydrosomes. This morphology suggests that carnosine is adsorbed on the vesicle surface and possibly embedded within the gel core, confirming efficient drug loading. Such structural characteristics align with other studies where nanoscale carriers demonstrated layered morphologies indicative of successful drug incorporation [35]. These features are indicative of a well-designed nanocarrier system optimized for stability and drug delivery functionality.

The faster initial release observed with CAR-HS can be attributed to the presence of nanocarriers (hydrosomes), which likely enhance the diffusion of carnosine compared to the CAR-GEL formulation. The hydrosomes may facilitate a rapid release of surface-adsorbed carnosine in the initial phase, followed by a sustained release from the gel core. In contrast, CAR-GEL relies on the diffusion of carnosine through the gel matrix, resulting in a slower release rate after the initial phase. This release profile aligns with studies on ethosomes and other vesicular carriers, which demonstrate similar biphasic release behaviours suitable for applications requiring rapid and prolonged action [36]. These findings highlight the potential of CAR-HS for applications requiring a faster onset of action, while CAR-GEL might be preferable for prolonged, controlled drug delivery.

The observed effects of CAR-HS treatment on skin rejuvenation can be attributed to the unique properties of hydrosomes. These nanoscale carriers create a hydrated microenvironment, support structural integrity, and promote wound healing. The enhanced transdermal penetration of carnosine encapsulated within hydrosomes likely plays a crucial role in skin hydration, repair, and wrinkle reduction. Similar findings have been reported in formulations utilizing ceramide-based nanocarriers, which demonstrated enhanced barrier repair and hydration [37]. Furthermore, the ability of CAR-HS to overcome the permeability limitations of the stratum corneum enhances its therapeutic potential as an anti-aging treatment. These findings highlight the synergistic benefits of carnosine and hydrosome technology in promoting skin rejuvenation and repair.

The significant reduction in MDA levels and improvement in CAT, SOD, and GSH levels highlight the robust antioxidant properties of carnosine, particularly when delivered via hydrosomes. The intrinsic antioxidant activity observed in HSblank suggests that hydrosomes themselves contribute to the overall oxidative stress reduction, likely due to the properties of their phospholipid components. A similar contribution of carrier systems to antioxidant effects was noted in lipid-based formulations containing tocopherol, where the carriers themselves exhibited additional protective properties [38].

The enhanced antioxidant activity of CAR-HS compared to CAR-GEL and HSblank can be attributed to several factors: the integration of carnosine with phospholipid vesicles that possess free radical scavenging potential, improved skin penetration facilitated by the nanoscale size of hydrosomes, and alterations in the stratum corneum bilayer structure. These characteristics collectively enable effective delivery of carnosine across the skin barrier, amplifying its protective and anti-glycation effects. In conclusion, the CAR-HS demonstrate significant potential as a nanocarrier system for the topical delivery of natural antioxidant agents, offering a promising therapeutic strategy for reversing D-gal-induced skin aging [39].

The observed statistically significant differences in RBC, Hb, WBC, and lymphocyte levels suggest the impact of the experimental treatments on hematological parameters. The improved RBC and Hb levels in treated groups may indicate a reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation caused by D-gal administration, supporting tissue repair and systemic recovery. Enhanced WBC and lymphocyte levels could reflect immunomodulatory effects of the treatments, potentially mediated by the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of carnosine or the hydrosomes. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the systemic benefits of nanocarriers loaded with bioactive agents, including improved hematological profiles in oxidative stress-induced models [40].

The histopathological findings highlight the potential therapeutic effects of carnosine formulations, particularly CAR-HS, in promoting skin tissue repair and mitigating the effects of D-gal-induced aging. The observed increase in collagen fiber deposition in CAR-HS-treated groups suggests enhanced extracellular matrix remodeling, which is critical for skin rejuvenation and structural integrity. The reduction in epidermal thickness and inflammatory markers in HSblank treated groups indicates that the hydrosome carriers themselves may possess inherent anti-inflammatory and tissue-repair properties. These effects, combined with carnosine's known antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, likely contribute to the observed reversal of skin aging markers. Such findings are consistent with reports of other antioxidant-loaded nanocarriers, where enhanced collagen deposition and reduced inflammation were noted [41]. Overall, these results suggest that both CAR-GEL and CAR-HS formulations support healing and reduce inflammation, with CAR-HS providing additional benefits due to its nanocarrier design, promoting enhanced therapeutic outcomes in skin rejuvenation and anti-aging applications.

The histopathological analysis of the spleen suggests that the D-gal-induced positive control group experienced oxidative stress-related damage. The presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages highlights the increased clearance of damaged red blood cells, likely resulting from oxidative stress induced by D-gal treatment. This aligns with the known effects of D-gal, which include increased oxidative stress and potential RBC damage. The normal histoarchitecture observed in carnosine and HSblank treated groups indicates the protective effects of these formulations against D-gal-induced spleen damage. The absence of toxic changes and maintenance of spleen structure in treated groups suggest that both carnosine and HSblank formulations mitigate oxidative stress and maintain spleen functionality, highlighting their potential therapeutic role in systemic protection. Similar protective effects on the spleen and other organs have been reported in studies evaluating antioxidant nanocarriers in oxidative stress models [42].

CONCLUSION

This study successfully developed and evaluated a CAR-HS designed to address D-gal-induced skin aging in a rat model. By leveraging the biocarrier system, CAR-HS exhibited superior physicochemical properties, sustained drug release, and significant anti-aging effects. The nanogel demonstrated enhanced antioxidant activity, reduced inflammation, and promoted tissue repair, outperforming conventional carnosine gel. Histopathological analysis further confirmed its safety. This innovative hydrosome nanoplatform highlights the potential of biocarrier technologies to amplify the therapeutic benefits of hydrophilic molecules like carnosine, offering a promising advancement in cosmetic dermatology for combating skin aging.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Gowtham Sundarrajan was responsible for the study design, manuscript preparation, and overall research coordination. Ariharasivakumar G contributed to data analysis and supervision, while Priyanka S focused on experimental execution and provided assistance in conducting the research.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Thakur R, Batheja P, Kaushik D, Michniak B. Structural and biochemical changes in aging skin and their impact on skin permeability barrier. In: Dayan N, editor. Skin aging handbook: an integrated approach to biochemistry and product development. Norwich (NY): William Andrew Publishing Incorporated; 2008.

Elias JJ. The microscopic structure of the epidermis and its derivatives. In: Barel AO, Paye M, Maibach HI, editors. Handbook of cosmetic science and technology. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2001.

Cohen J. Dermis epidermis and dermal papillae interacting. In: Montagna W, Dobson RL, editors. Advances in biology of skin. Vol. IX, Hair Growth. Oxford: Pergamon; 1969. p. 1-18.

Scully JL. What is a disease? EMBO Rep. 2004;5(7):650-3. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400195, PMID 15229637.

Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC, German National Genome Research Network 2. The skin as a mirror of the aging process in the human organism state of the art and results of the aging research in the German National Genome Research Network 2 (NGFN-2). Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(9):879-86. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.07.002, PMID 17689905.

Lener T, Moll PR, Rinnerthaler M, Bauer J, Aberger F, Richter K. Expression profiling of aging in the human skin. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(4):387-97. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.01.012, PMID 16530368.

Chiang YJ, Difilippantonio MJ, Tessarollo L, Morse HC, Hodes RJ. Exon 1 disruption alters tissue-specific expression of mouse p53 and results in selective development of B cell lymphomas. Plos One. 2012;7(11):e49305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049305, PMID 23166633.

Kimball AB, Alora Palli MB, Tamura M, Mullins LA, Soh C, Binder RL. Age-induced and photoinduced changes in gene expression profiles in facial skin of caucasian females across six decades of age. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.012.

Laga AC, Murphy GF. The translational basis of human cutaneous photoaging: on models methods and meaning. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(2):357-60. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081029, PMID 19147830.

Wilson N. Market evolution of topical antiaging treatments. In: Dayan N, editor. Skin aging handbook: an integrated approach to biochemistry and product development. Norwich (NY): William Andrew Publishing Incorporated; 2008.

Klatz R, Goldman R. Stopping the clock. New Canaan (CT): Keats Publishing; 1997.

Ward DM. Cross linkage theory of aging: Part IV. Vitam Res Prod; 2000.

South J. The free radical theory of aging. Int Aging Syst; 2005.

Magalhaes JP. Telomeres Telomerase; 2005.

Lehn JM. Toward self-organization and complex matter. Science. 2002;295(5564):2400-3. doi: 10.1126/science.1071063, PMID 11923524.

Donaldson K, Stone V, Tran CL, Kreyling W, Borm PJ. Nanotoxicology. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(9):727-8. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.013243, PMID 15317911.

Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(7):823-39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339, PMID 16002369.

Mezei M, Gulasekharam V. Liposomes a selective drug delivery system for the topical route of administration. Lotion dosage form. Life Sci. 1980;26(18):1473-7. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90268-4, PMID 6893068.

Handjani Vila RM, Ribier A, Rondot B, Vanlerberghie G. Dispersions of lamellar phases of non ionic lipids in cosmetic products. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1979;1(5):303-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.1979.tb00224.x, PMID 19467076.

Touitou E, Dayan N, Bergelson L, Godin B, Eliaz M. Ethosomes novel vesicular carriers for enhanced delivery: characterization and skin penetration properties. J Control Release. 2000;65(3):403-18. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00222-9, PMID 10699298.

Elsheikh MA, Gaafar PM, Khattab MA, A Helwah MK, Noureldin MH, Abbas H. Dual effects of caffeinated hyalurosomes as a nano cosmeceutical gel counteracting UV induced skin ageing. Int J Pharm X. 2023;5(1):100170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2023.100170, PMID 36844895.

Aiyalu R, Govindarjan A, Ramasamy A. Formulation and evaluation of topical herbal gel for the treatment of arthritis in animal model. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2016;52(3):493-507. doi: 10.1590/s1984-82502016000300015.

Khazaeli P, Pardakhty A, Shoorabi H. Caffeine loaded niosomes: characterization and in vitro release studies. Drug Deliv. 2007;14(7):447-52. doi: 10.1080/10717540701603597, PMID 17994362.

Kumari A, Rana V, Yadav SK, Kumar V. Nanotechnology as a powerful tool in plant sciences: recent developments challenges and perspectives. Plant Nano Biol. 2023 Aug;5:100046. doi: 10.1016/j.plana.2023.100046.

Ahmed N, Sohail MF, Khurshid Z, Ammar A, Saeed AM, Shazia F. Synthesis characterization and in vivo distribution of 99mTc radiolabelled docetaxel loaded folic acid thiolated chitosan enveloped liposomes. Bio Nano Science. 2023;13(1):134-44. doi: 10.1007/s12668-022-01053-2.

r48

Thrix

If this is a journal title, it’s unknown to Thrix.

Kumari A, Rana V, Yadav SK, Kumar V. Nanotechnology as a powerful tool in plant sciences: recent developments challenges and perspectives. Plant Nano Biol. 2023 Aug;5:100046. doi: 10.1016/j.plana.2023.100046.

Khazaeli P, Pardakhty A, Shoorabi H. Caffeine loaded niosomes: characterization and in vitro release studies. Drug Deliv. 2007;14(7):447-52. doi: 10.1080/10717540701603597, PMID 17994362.

Ahmed N, Sohail MF, Khurshid Z, Ammar A, Saeed AM, Shazia F. Synthesis characterization and in vivo distribution of 99mtc radiolabelled docetaxel loaded folic acid thiolated chitosan enveloped liposomes. Bio Nano Science. 2023;13(1):134-44. doi: 10.1007/s12668-022-01053-2.

Salunkhe SS, Bhatia NM, Pokharkar VB, Thorat JD, Bhatia MS. Topical delivery of idebenone using nanostructured lipid carriers: evaluations of sun protection and anti-oxidant effects. J Pharm Investig. 2013;43(4):287-303. doi: 10.1007/s40005-013-0079-y.

Ghanbarzadeh B, Babazadeh A, Hamishehkar H. Nano phytosome as a potential food-grade delivery system. Food Bioscience. 2016 Sep 1;15:126-35. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2016.07.006.

Abd El Alim SH, Kassem AA, Basha M, Salama A. Comparative study of liposomes ethosomes and transfersomes as carriers for enhancing the transdermal delivery of diflunisal: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2019 May 30;563:293-303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.04.001, PMID 30951860.

Dragovic RA, Gardiner C, Brooks AS, Tannetta DS, Ferguson DJ, Hole P. Sizing and phenotyping of cellular vesicles using nanoparticle tracking analysis. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(6):780-8. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.003, PMID 21601655.

Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani FH, Javanmard R, Dokhani A. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057, PMID 29783687.

Rabbani M, Pezeshki A, Ahmadi R, Mohammadi M, Tabibiazar M, Ahmadzadeh Nobari Azar F. Phytosomal nanocarriers for encapsulation and delivery of resveratrol preparation characterization and application in mayonnaise. LWT. 2021;151:2021.112093. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112093.

Zhang W, Taheri Ledari R, Ganjali F, Mirmohammadi SS, Qazi FS, Saeidirad M. Effects of morphology and size of nanoscale drug carriers on cellular uptake and internalization process: a review. RSC Adv. 2022;13(1):80-114. doi: 10.1039/d2ra06888e, PMID 36605676.

Touitou E, Dayan N, Bergelson L, Godin B, Eliaz M. Ethosomes novel vesicular carriers for enhanced delivery: characterization and skin penetration properties. J Control Release. 2000 Apr 3;65(3):403-18. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00222-9, PMID 10699298.

Vovesna A, Zhigunov A, Balouch M, Zbytovska J. Ceramide liposomes for skin barrier recovery: a novel formulation based on natural skin lipids. Int J Pharm. 2021 Mar 1;596:120264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120264, PMID 33486027.

LU H, Zhang S, Wang J, Chen Q. A review on polymer and lipid based nanocarriers and its application to nano pharmaceutical and food based systems. Front Nutr. 2021 Dec 1;8:783831. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.783831, PMID 34926557, PMCID PMC8671830.

Parameshwaran K, Irwin MH, Steliou K, Pinkert CA. D-galactose effectiveness in modeling aging and therapeutic antioxidant treatment in mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13(6):729-35. doi: 10.1089/rej.2010.1020, PMID 21204654.

Jarmila P, Veronika M, Peter M. Advances in the delivery of anticancer drugs by nanoparticles and chitosan based nanoparticles. Int J Pharm X. 2024 Aug 28;8:100281. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2024.100281, PMID 39297017.

Nasrullah MZ. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester loaded PEG-PLGA nanoparticles enhance wound healing in diabetic rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Dec 27;12(1):60. doi: 10.3390/antiox12010060, PMID 36670922, PMCID PMC9854644.

MU J, LI C, Shi Y, Liu G, Zou J, Zhang DY. Protective effect of platinum nano-antioxidant and nitric oxide against hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury. Nat Commun. 2022 May 6;13(1):2513. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29772-w, PMID 35523769, PMCID PMC9076604.