Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 5, 17-24Original Article

EFFICACY EVALUATION OF COMMERCIAL HAND SANITIZERS ON COMMON BACTERIAL PATHOGENS

MEBAAIHUN THANGKHIEW, VISHAL KUMAR MOHAN, NIRMALA AKOIJAM, SANTA RAM JOSHI*

Department of Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong-793022, India

*Corresponding author: Santa Ram Joshi; *Email: srjoshi2006@gmail.com

Received: 03 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 13 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The present study aimed to check the efficiency of commercially available hand sanitisers against some identified bacterial pathogens.

Methods: An agar well diffusion experiment was used to assess the anti-bacterial effectiveness of five commercially available hand sanitisers. Bacterial growth inhibition was evaluated, and the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of each sanitiser were determined. The effects of the sanitisers on bacteria were visually examined using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

Results: The agar well diffusion assay demonstrated highest inhibition of the pathogenic bacterial strains Staphylococcus aureusM96, Escherichia coliM730 and Bacillus subtilis M441 by sanitizer C1, whereas sanitizers C4, C2, and C5 showed no inhibition. Growth curve analysis of the test bacterial strains showed minimum OD when present with C3 indicating its potent anti-bacterial activity. C3 had the lowest values at 2% v/v, according to the MIC and MBC data, followed by C1, C4, and C2. Significant disruption and structural abnormalities were seen in SEM pictures of C3 and C1-treated bacterial cells.

Conclusion: Not all sanitizers that are commercially available are effective against common disease-causing bacteria or pathogens. There is an urgent need for establishment of stricter government regulations that ensures the availability of only effective sanitizers to curb the spread of communicable diseases.

Keywords: Sanitizers, Pathogens, MIC, MBC, SEM

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i5.53583 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Hand hygiene is a simple and effective measure to prevent infections and reduce disease transmission [1]. Hands can easily be contaminated through direct or indirect contact with pathogens and can cause health issues hence hand washing with water and soap has to be done in the proper way as described by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2, 3] to effectively remove all pathogens and other harmful substances. The outbreak of the recent Covid-19 pandemic and the increased demand for hand sanitizers have seen an upsurge in the development of hand sanitizers formulations, which validated the regulatory bodies such as Food and Drug Administration(FDA), WHO, United States Pharmacopeia (UPS) and Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), which have standard guidelines for the formulation of sanitizers [4]. Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of alcohol-based hand sanitizers against a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi and viruses but they have also been reported to have very poor activity against bacterial spores, protozoan oocysts and certain non-enveloped (non-lipophilic) viruses [5]. Alcohol alters protein function through direct protein interaction and lead to cell desiccation [6]. Ethanol forms hydrogen bonds with the lipids in the bilayer and these hydrogen bonds reduces the order parameter of the lipid hydrocarbon chains, resulting in the easy penetration of ethanol through the bilayer [7]. Absolute ethanol, a dehydrating agent is less bactericidal than mixtures of alcohol and water because proteins are denatured more quickly in presence of water [8]. However, higher concentrations of ethanol (e.g., 95%) generally have been found to have better viricidal activity than lower concentrations (60% to 80%), especially against naked viruses [9]. Gram-negative bacteria are more susceptible to alcohol as compared to Gram-positive bacteria with thick wall of peptidoglycan [10].

Non-alcohol-based hand sanitizers such as Benzalkonium chloride, a quaternary ammonium compound with a cationic head group is absorbed by the negative charged phosphate heads of phospholipid bilayers which disrupt the cell structural integrity [11]. The antibacterial mode of action of various alcohol-based hand sanitizer (ABHS) and non-alcohol-based hand sanitizer (NABHS) can be evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which provides the visual characteristics of surfaces of various cells. SEM able to monitor size, size distribution and morphology of cells with high magnification [12]. The present study used SEM for comparing the morphology of hand sanitizers treated and untreated cells and analysed the micrograph to understand the effects of the sanitizers on the bacterial cells apart from the observation made on the growth of bacteria in presence of sanitizers in agar diffusion assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Glutaraldehyde, sodium cacodylate, acetone, tetra-methyl silane, Mueller–Hinton agar, etc.

Agar well diffusion assay

The susceptibility of the test bacterial pathogens, namely, Staphylococcus aureus M96, Bacillus subtilis M441 and Escherichia coli M730, which was procured from IMTECH Chandigarh was tested against the five commercially available hand sanitizers and was investigated using the well variant of the agar diffusion method [13, 14]. Distilled water was used as a negative control.

On an MHA plate, 100 μl of each bacterial microbiological culture was swabbed separately. A sterile borer was used to create wells that were 5 mm in diameter. Each well was filled with 80 μl of the control, 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% concentration of hand sanitizers [14]. For twenty-four hours, the plates were incubated at 37±2 °C. The zone formation surrounding the wells was detected on the plates. The diameter of the inhibition zone surrounding the well (in millimetres), including the well diameter, was used to compute the zone of inhibition [15].

Measurement of bacterial growth

Assessment of the chosen bacterial growth in presence of the sanitizers in broth culture was done by measuring the optical density at 600 nm following standard protocols of Oke et al., 2013 [5] and Aburayan et al., 2020 [16]. 100 μl of 0.5 McFarland solution of bacterial inoculum was added to the broth, and the inoculated flasks were incubated at 37 °C at 120 rpm. Absorbance (Eppendorf BioPhotometer® D30) was recorded every 30 min for 5 h to obtain a microbial growth curve.

Assessment of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) approach and zone of inhibition calculation, the antibacterial activity of sanitisers against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria was determined as described by Gupta, 2021 [17]. The MBC of the selected hand sanitizers were determined against the three bacterial strains, namely, S. aureus M96, B. subtilis M441 and E. coli M730 following the method of Aodah et al. 2021 [11] with minor modifications. Different dilutions of the sanitizers were prepared in Mueller-Hinton broth according to their inhibitory effects observed in the test. 100μl of 0.5 McFarland bacterial inoculum was added to each tube and the culture tubes along with the control (bacteria without sanitizer) were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a shaker incubator at 120 rpm for 24 h [18]. Absorbance was taken at 600 nm (Eppendorf BioPhotometer® D30).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of treated cells

Scanning electron microscopy was performed following the protocol of Yong et al., 2014 [19] and Dey,1993 [20]. The common pathogens S. aureus, B. subtilis and E. coli were grown overnight in Mueller Hinton Broth. Agar well diffusion assay was performed overnight by incubating the treated cultures at 37 °C. The cells from the periphery of the zone of inhibition were collected in centrifuge tubes along with the colonies from the control. The samples were then centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 15 min and the pellet was further processed for SEM analysis. All of the eight samples were fixed with 2.5% w/v aqueous glutaraldehyde overnight at 4 °C. The samples were then washed in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer for three changes with 15 min each at 4 °C with the centrifugation of the sample. The fixed samples were then dehydrated by rinsing with increasing concentration of acetone from 30, 50, 70, 80, 90, 95 and 100% for 15 min twice for each concentration. The dehydrated samples were then immersed in Tetra Methyl Silane for 10 min for two changes at 4 °C and brought to room temperature (25-26 °C) for drying. After keeping the samples at room temperature overnight, the samples were crushed gently and powdered and kept in the dry bath at 50 °C for proper drying. Then the dried sample materials were mounted onto stubs and coated by a sputter Coater (Ion Sputter JFC-1100) with gold. The samples were then examined in Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL JSM-6360) at 5000x and 10000x magnification each.

RESULTS

Agar-well diffusion assay

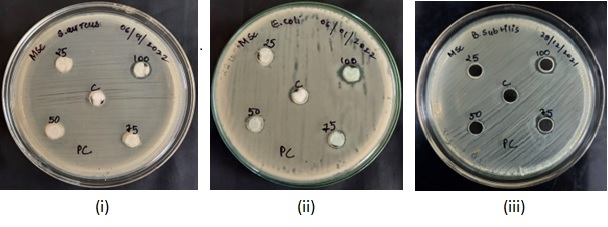

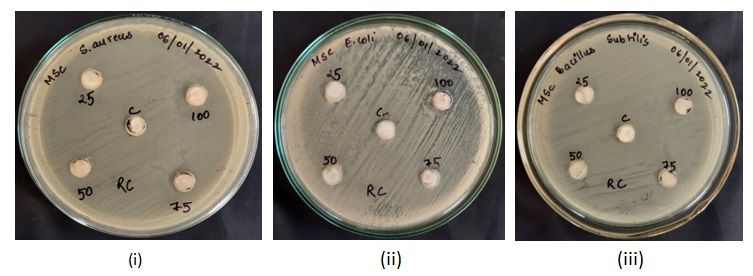

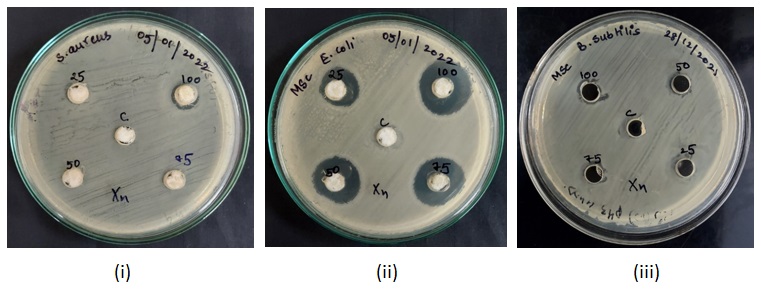

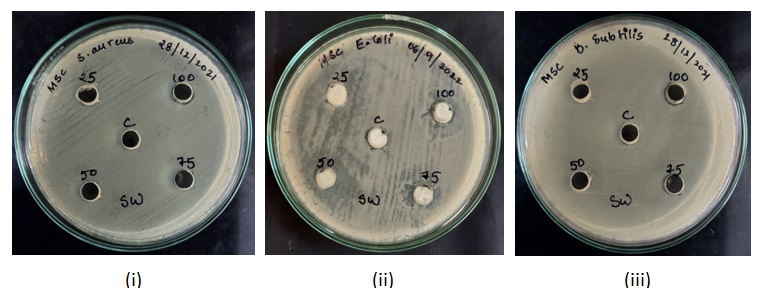

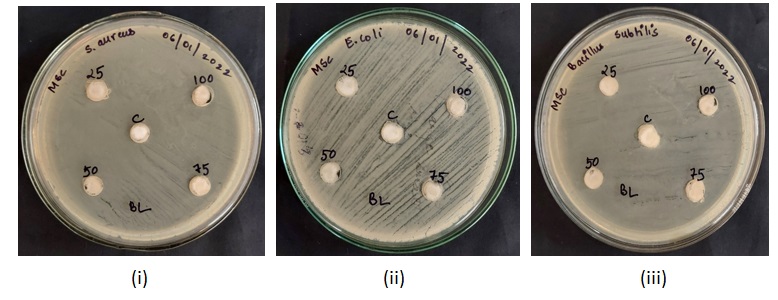

The diameters of well-defined zones of inhibition i. e., areas of no bacterial growth increased with increasing concentration of the hand sanitizers (table 1, 2 and 3).50% concentration of sanitizer C1 inhibited the growth of Escherichia coli and at 100% concentration, it showed a uniform trend of inhibition zones (around 11 mm in diameter) (table 1). Similarly, sanitizers C3 and C4 also demonstrated highest inhibitions at 100% concentration (tables 2 and 3).

Table 1: Zone of inhibition observed for commercially available hand sanitizer C1

| Bacterial strain | Zone of inhibition diameter (mm) | ||||

| Control | 25% concentration | 50% concentration | 75% concentration | 100% concentration | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.10±0.021 | 11.30±0.058 |

| Escherichia coli | 0 | 0 | 8.54±0.033 | 9.05±0.025 | 11.00±0.023 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.15±0.045 | 11.20±0.033 |

Each value is represented as mean±standard error of mean (n=3)

Fig. 1: MHA plates showing zones of inhibition caused by sanitizer C1 against (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Fig. 2: MHA plates showing zones of inhibition caused by sanitizer C2 against (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Table 2: Zones of inhibitions observed for the commercially available hand sanitizer C3

| Bacterial strain | Zone of inhibition (mm) | ||||

| Control | 25% concentration | 50% concentration | 75% concentration | 100% concentration | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.22±0.022 |

| Escherichia coli | 0 | 15.10±0.034 | 19.25±0.054 | 21.89±0.031 | 23.42±0.023 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0 | 0 | 8.33±011 | 9.21±0.011 | 10.11±0.042 |

Each value is mean±standard error of mean (n=3)

Fig. 3: MHA plates showing zones of inhibition caused by sanitizer C3 against (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Table 3: Zones of inhibition observed for commercially available hand sanitizer C4

| Bacterial strain | Zone of inhibition diameter (mm) | ||||

| Control | 25% concentration | 50% concentration | 75% concentration | 100% concentration | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.11±0.013 |

| Escherichia coli | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.78±0.030 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.76±0.022 | 10.24±0.024 |

Each value is mean±standard error of mean (n=3)

Fig. 4: MHA plates showing zones of inhibition caused by sanitizer C4 against (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Fig. 5: MHA plates showing zones of inhibition caused by sanitizer C5 against (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

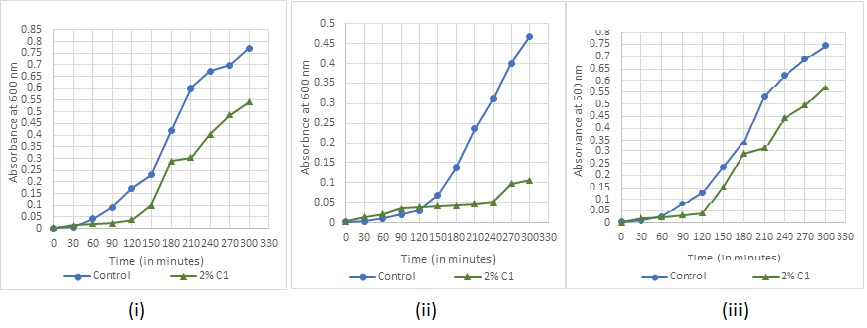

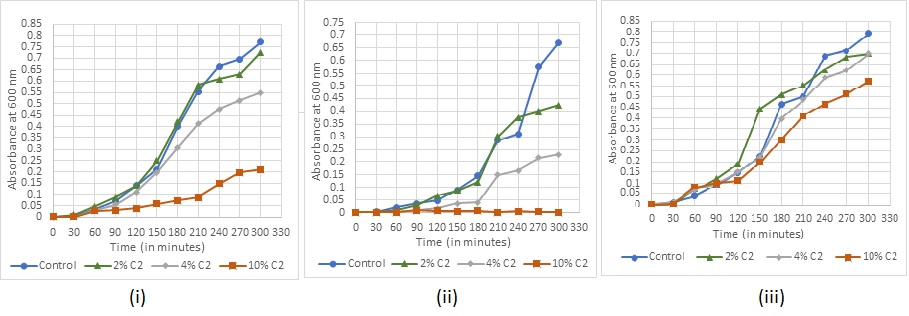

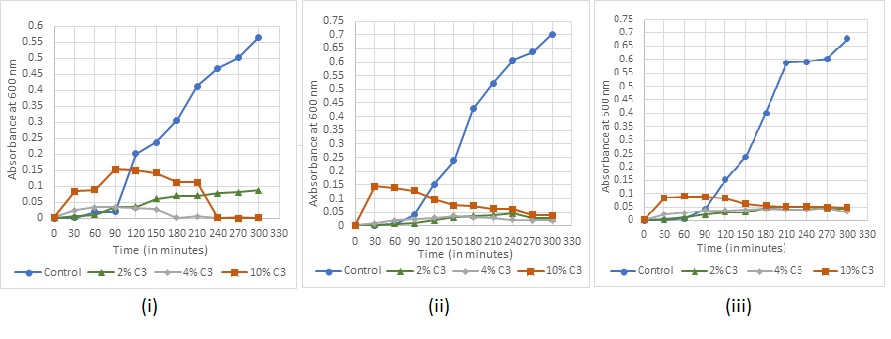

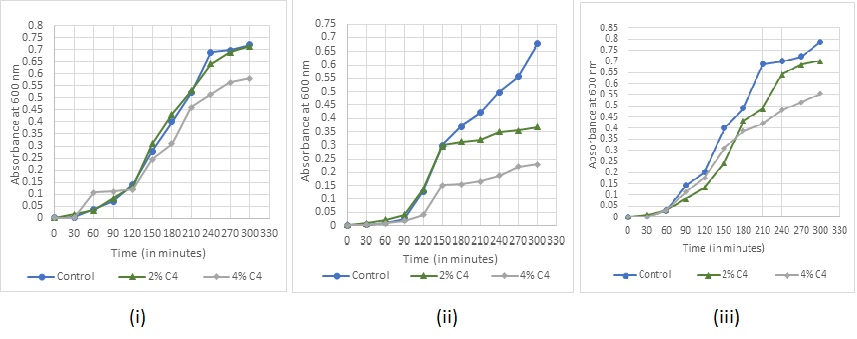

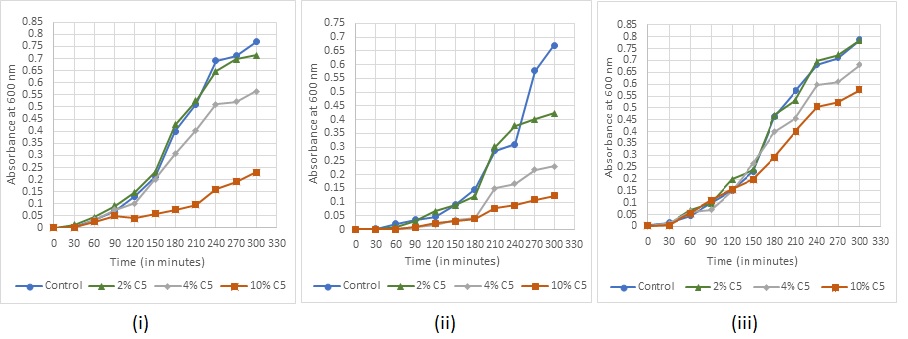

Growth measurement of the bacteria under treatment

Absorbance readings for detection of growth in the various concentrations of the sanitizers were taken at every 30 min for (fig. 7-11). The recorded growth curves further validate the efficacy of the sanitizers against inhibiting the growth of the test pathogens. It can be observed that with increasing concentrations of the sanitizer, there is a proportionate decrease in the growth of the pathogens thereby reaffirming the bactericidal activity of these selected sanitizers.

Fig. 7: Bacterial growth under sanitizer C1 treatment for (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Fig. 8: Bacterial growth under sanitizer C2 treatment (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Fig. 9: Bacterial growth under sanitizer C3 treatment (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Fig. 10: Bacterial growth under sanitizer C4 treatment (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Fig. 11: Bacterial growth under sanitizer C5 treatment (i) Staphylococcus aureus (ii) Escherichia coli (iii) Bacillus subtilis

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) study

The MIC and MBC of the 5 sanitizers varied for different bacteria (table 4 and 5). The lowest MIC recorded was 2% v/v for sanitizer C3 against all the 3 bacterial strains, followed by C1, C4 and C2 while the highest was for C5 with MIC values of 15% v/v for S. aureus and E. coli and 25% v/v for B. subtilis (table 4).

The lowest MBC recorded was 8% v/v, where there was no growth on the agar plate for C1 and C3 against E. coli. Highest MBC recorded was 30% for C5 (table 5).

Table 4: Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the 5 commercially available hand sanitizers (C1, C2, C3, C4 and C5) against S. aureus, E. coli and B. subtilis

| Bacterial strain | Commercially available hand sanitizers and concentration used (%) | ||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6.21±0.021 | 15.28±0.023 | 2.45±0.011 | 6.71±0.043 | 15.77±0.021 |

| Escherichia coli | 2.33±0.014 | 10.15±0.022 | 2.49±0.04 | 4.76±0.033 | 15.00±0.6 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 4.17±0.16 | 20.23±0.3 | 2.21±0.01 | 6.34±0.2 | 25.20±0.9 |

Each value is mean±standard error of mean (n=3)

Table 5: MBC of the 5 commercially available hand sanitizers (C1, C2, C3, C4 and C5) against S. aureus, E. coli and B. subtilis

| Bacterial strain | Commercially available hand sanitizers and concentration used | ||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 10.12±0.014 | 25.26±0.038 | 10.29±0.2 | 10.81±0.046 | 30.91±0.4 |

| Escherichia coli | 8.73±0.023 | 30.60±0.6 | 8.61±0.04 | 10.58±0.1 | 30.46±0.6 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 10.72±0.16 | 20.62±0.3 | 10.52±0.2 | 15.82±0.012 | 30.38±0.9 |

Each value is mean±standard error of mean (n=3)

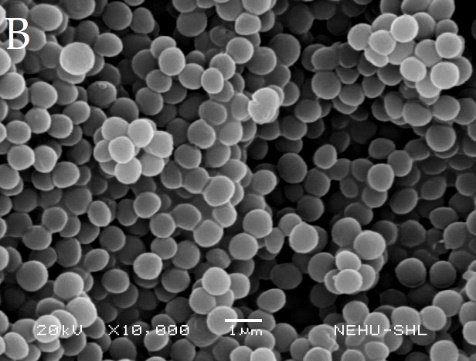

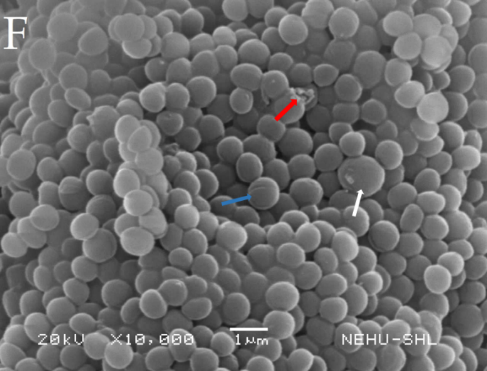

Scanning electron microscopy study

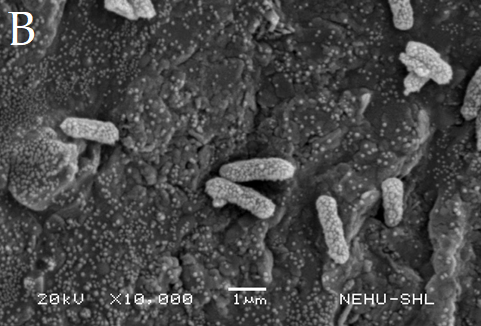

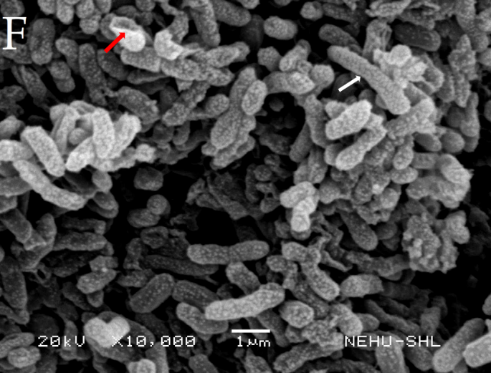

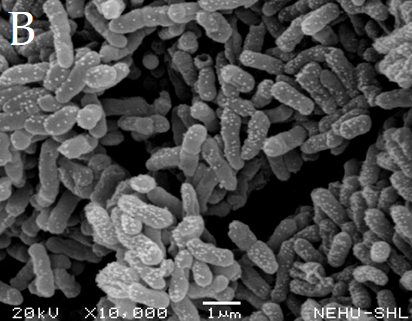

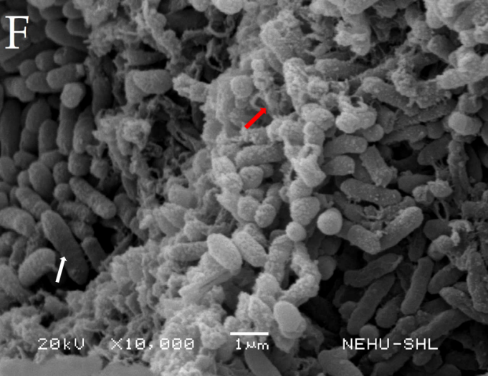

Significant changes were observed in the cell membrane of the treated cells when compared with the control (fig. 12, 13, 14 and 15). There were changes associated with the cell size along with cell membrane rupture.

S. aureus treated with 75% of C1, when compared to the control (B) showed increased size of some cells and a few ruptured cells (F). There are cells with cleavage on the surface (F) (fig. 12).

E. coli treated with 75% of C1 developed elongated rod-shaped cells (D) when compared to the control (B) there are a few cells that developed rupture after sanitizer treatment (fig. 13)

E. coli treated with 25% of sanitizer C3, showed elongation of the cells and rupture in the cell membrane (F) as compared to the control (B) (fig. 14)

B. subtilis treated with 75% of sanitizer C3 has a large number of ruptured cells. The cell membrane is punctured and the cell components look degraded (F) as compared to the control (B) (fig. 15).

Fig. 12: Electron micrographs of untreated Staphylococcus aureus (B), Treated with 75% sanitizer C1 (F). White arrow indicates cell increased in size, red arrow indicates ruptured cell and blue arrow indicates cells with cleavage on the surface

Fig. 13: Electron micrographs of untreated Escherichia coli (B) Treated with 75% sanitizer C1 (D). White arrow indicates cell increased in size and red arrow indicates ruptured cell

Fig. 14: Electron micrographs of untreated Escherichia coli (B) Treated with 25% sanitizer C3 (F). White arrow indicates cell increased in size and red arrow indicates ruptured cell

Fig. 15: Electron micrographs of untreated Bacillus subtilis (B), Treated with 75% sanitizer C3 (F). White arrow indicates cell increased in size and red arrow indicates ruptured cell

DISCUSSION

The necessity for efficient antimicrobial formulations has been highlighted by the growing usage of hand sanitisers, especially during the COVID-19 epidemic. Alcohol-based hand sanitisers are well known for their quick bactericidal action, which is mostly achieved via lipid breakdown, membrane disruption, and protein denaturation [21]. However, it seems that they are not very effective against viruses that are not enclosed [22]. Alcohol also evaporates quickly, which lessens its potency over time.

Hand hygiene is critical in reducing healthcare-associated infections, which cause an estimated 90,000 fatalities in the United States each year [23]. Pathogen cross-transmission, particularly between g-negative bacteria like E. coli and Pseudomonas and g-positive bacteria like S. aureus, is a major cause of nosocomial infections [23]. The abundance of germs on human skin (10² to 10⁶ CFU/cm²) emphasises the need for appropriate hand sanitisation treatments.

On evaluation of the efficacy of the commercially available sanitizers (Name withhold for business ethics), Sanitiser C3 (non-alcohol-based) was found to be the most efficient against a variety of pathogens, outperforming alcohol-based choices such as Sanitiser C1. This finding shows that the active compounds in C3, which could include antibacterial agents such as benzalkonium chloride or chlorhexidine [11], provide a stronger, long-lasting antimicrobial action than alcohol, which evaporates fast and loses effectiveness when dried [5]. While alcohol-based hand sanitisers are efficient for immediate pathogen control, non-alcohol alternatives such as Sanitiser C3 may provide greater overall efficacy, particularly in environments with specific microbiological difficulties or where long-term protection is needed. The other sanitizers, namely, C4, C2 and C5 did not show zones of inhibition in the agar well diffusion assay and were not able to show inhibition at lower concentrations, even in broth, when tested against all the bacterial strains.

These findings underline the importance of strict quality assurance in the sanitiser sector, as well as the potential for long-term microbial suppression with non-alcohol-based formulations. While alcohol-based sanitisers are still efficient at eradicating pathogens quickly, non-alcohol alternatives may be better suited for places that require long-term antimicrobial protection, such as healthcare facilities. Additional research is needed to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of these formulations in real-world settings.

CONCLUSION

Compared to alcohol-based Sanitiser C1, non-alcohol-based Sanitiser C3 was more effective against a variety of infections and provided longer-lasting protection. The lack of antibacterial activity displayed by the other sanitisers (C2, C4, and C5) suggests that many commercially available solutions might not be very helpful at preventing diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Sophisticated Analytical Instrumentation Facility (SAIF), NEHU, Shillong for providing the facilities to perform SEM.

FUNDING

No funding was taken during the study.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

FDA-Food and Drug administration, WHO-World Health Organization, UPS-United States Pharmacopeia, CDSCO-Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, CDC-Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, MIC-Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, MBC-Minimum Bactericidal concentration, ABHS-alcohol based hand sanitizer, NABHS-non-alcohol-based hand sanitizer, SEM-Scanning electron microscope, Mm-Millimetre

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

S. R. Joshi and Vishal Kumar Mohan designed the experiments for the study, Mebaaihun Thangkhiew performed the necessary experimental works and Nirmala Akoijam performed the sample preparation for SEM followed by data analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

CDC. Hand sanitizer use out and about; 2021. Available from: www.cdc.gov/handwashing/hand-sanitizer-use.html.

WHO. Guide to local production: WHO-recommended hand rub formulations; 2010. Available from: www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Guide_to_Local_Production.pdf.

WHO. List of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed; 2017. Available from: www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed.

Singh D, Joshi K, Samuel A, Patra J, Mahindroo N. Alcohol-based hand sanitisers as first line of defence against SARS-CoV-2: a review of biology, chemistry and formulations. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e229. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002319, PMID 32988431.

Oke MA, Bello AB, Odebisi MB, Ahmed El-Imam AM, Kazeem MO. Evaluation of antibacterial efficacy of some alcohol-based hand sanitizers sold in Ilorin (North-central Nigeria). Life J Sci. 2013;15:111-7.

Ingólfsson HI, Andersen OS. Alcohol’s effects on lipid bilayer properties. Biophys J. 2011;101(4):847-55. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.013, PMID 21843475.

Patra M, Salonen E, Terama E, Vattulainen I, Faller R, Lee BW. Under the influence of alcohol: the effect of ethanol and methanol on lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2006;90(4):1121-35. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062364, PMID 16326895.

McKeen L. Introduction to food irradiation and medical sterilization. In: The effect of sterilization on plastics and elastomers. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. p. 1-40. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-2598-4.00001-0.

Kampf G, Kramer A. Epidemiologic background of hand hygiene and evaluation of the most important agents for scrubs and rubs. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):863-93. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.863-893.2004, PMID 15489352.

Man A, Gaz AS, Mare AD, Berţa L. Effects of low-molecular-weight alcohols on bacterial viability. Rev Romana Med Lab. 2017;25(4):335-44. doi: 10.1515/rrlm-2017-0028.

Aodah AH, Bakr AA, Booq RY, Rahman MJ, Alzahrani DA, Alsulami KA. Preparation and evaluation of benzalkonium chloride hand sanitizer as a potential alternative for alcohol-based hand gels. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(8):807-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.06.002, PMID 34408542.

Wen S, Liu J, Deng J. Methods for the detection and composition study of fluid inclusions. In: Fluid inclusion effect in flotation of sulfide minerals. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. p. 27-68. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-819845-2.00003-X.

Valgas C, de Souza SM, Smânia EF, Smania Jr A. Screening methods to determine antibacterial activity of natural products. Braz J Microbiol. 2007;38(2):369-80. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822007000200034.

Thamaraikani V, Amala S Divya, Sekar T. Analysis of the phytochemicals, antioxidants, and antimicrobial activity of ficustsjahelaburm. F leaf, bark, and fruit extracts; 2021. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021v14i2.40185.

Jyothi D, Priya S, James JP. Antimicrobial potential of hydrogel incorporated with plga nanoparticles of crossandra infundibuliformis. Int J Appl Pharm. 2019;11:1-5. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2019v11si2.31289.

Aburayan WS, Booq RY, BinSaleh NS, Alfassam HA, Bakr AA, Bukhary HA. The Delivery of the novel drug ‘Halicin’ using electrospun fibers for the treatment of pressure ulcer against pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(12):1189. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121189, PMID 33302338.

Gupta M. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using catharanthus roseus and their antibacterial efficacy in synergy with antibiotics; a future advancement in nanomedicine. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2021;14:2. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021v14i2.39856.

Kamgang R, Gaetanolivier F, Tetkajacqueline N, Kamgahortense G, Andchristine M. Antimicrobial and antidiarrheal effects of four cameroon medicinal plants: dichrocephala integrifolia, dioscoreapreusii, melenisminutiflora, and tricalysiaokelensis; 2015.

Yong AL, Ooh KF, Ong HC, Chai TT, Wong FC. Investigation of antibacterial mechanism and identification of bacterial protein targets mediated by antibacterial medicinal plant extracts. Food Chem. 2015;186:32-6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.103, PMID 25976788.

Dey S. A new rapid air-drying technique for scanning electron microscopy using tetramethylsilane: application to mammalian tissue. Cytobios. 1993;73(292):17-23. PMID 8500345.

Jain VM, Karibasappa GN, Dodamani AS, Prashanth VK, Mali GV. Comparative assessment of antimicrobial efficacy of different hand sanitizers: an in vitro study. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2016;13(5):424-31. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.192283, PMID 27857768.

Foddai AC, Grant IR, Dean M. Efficacy of instant hand sanitizers against foodborne pathogens compared with hand washing with soap and water in food preparation settings: a systematic review. J Food Prot. 2016;79(6):1040-54. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-492, PMID 27296611.

Sickbert Bennett EE, Weber DJ, Gergen Teague MF, Sobsey MD, Samsa GP, Rutala WA. Comparative efficacy of hand hygiene agents in the reduction of bacteria and viruses. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33(2):67-77. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.08.005, PMID 15761405.