Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 5, 1-7Review Article

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS: ELUSIVE PERSPECTIVES AND NOVEL VACCINATION APPROACHES

ASHISH S. RAMTEKE*

Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology, Nagpur-440010, India

*Corresponding author: A. S. Ramteke; *Email: asramteke1992@gmail.com

Received: 01 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 23 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

A Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) vaccine is a critical component in the effort to manage the global epidemic. To assess the current state of HIV vaccine development, we analyze the findings of effectiveness trials conducted to date, as well as the immunological principles that drove them. Four vaccine approaches have been evaluated in HIV-1 vaccine effectiveness trials. The results have offered valuable information for future vaccine development. While one of these trials demonstrated that a safe and effective HIV vaccine is feasible, numerous issues remain about the basis for the observed protection and the most effective strategy to stimulate it. Novel HIV vaccination techniques, such as inducing highly potent broadly neutralizing antibodies, novel homologous and heterologous vector systems, and vectored immunoprophylaxis, aim to expand and build on the knowledge obtained from previous trials.

Keywords: HIV, Vaccine, T-cells, B-cells, RV144, HVTN 505

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i5.53841 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Despite nearly 30 years of continuous research, there is still no Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) vaccine. Effective vaccinations often stimulate protective immunity equivalent to that observed during natural illness. However, naturally acquired immunity to HIV infection may not exist, posing an unprecedented barrier for vaccine development. As a result, the mechanism by which an HIV vaccine may provide protection remains unknown. An effective vaccination may necessitate the activation of an immune response that differs dramatically from that seen during natural infection [1]. The enormous diversity of HIV adds to the difficulty of vaccine development. Considering its recent origins, HIV, particularly HIV-1, has astonishing diversity. Within the primary HIV-1 subtype, Group M, there are nine clades as well as dozens of recombinant forms, with clades varying by up to 42% in amino acid sequence. A vaccine immunogen produced from one clade may be ineffective against others, offering a substantial challenge to the development of a worldwide HIV vaccine [2].

We explore the present state of HIV vaccine research by analyzing the outcomes of candidate HIV vaccine effectiveness trials and the immunologic ideas that drove them. We also examine novel strategies that aim to improve on the approaches used in those trials. Therefore, four vaccination ideas have been examined in efficacy trials [3]. The VAX004 and VAX003 trials assessed the initial concept, a protein subunit vaccination. The Step and HIV Vaccine Studies Network (HVTN) 503/Phambili trials examined the second approach, a recombinant adenovirus vector. The RV144 trial investigated the third strategy, which involved priming a canarypox vector with a protein subunit boost [4]. The HVTN 505 study recently evaluated the fourth approach, which is a DNA prime followed by a recombinant adenovirus vector boost (table 1).

Table 1: HIV vaccine effectiveness trials and immunological response

| Trial | Vaccine | Population | N | Efficacy | Immune response | Reference |

| VAX004 | AIDSVAX B/B | Primarily high-risk MSM | 5403 | None | Weak nAb response | [26] |

| VAX003 | AIDSVAX B/E | Injection drug users | 2546 | None | Weak nAb response | [50] |

| HVTN 503/Phambili | MRKAd5 HIV-1 | Primarily heterosexuals | 801 | None | CD8+T-cell response | [31] |

| RV144 | ALVAC prime followed by AIDSVAX B/E boost | Primarily low-risk heterosexuals |

16,402 | 31.2% overall efficacy | Weak nAb response | [17] |

| HVTN 505 | VRC-HIVDNA 16-00-VP boost | High-risk MSM | 2504 | None | Awaiting final trial results | [10] |

Viral diversity, glycans, and latency

The search for a HIV vaccine has been a rocky 40 y path fraught with difficulties. One of the most critical obstacles is the HIV-1 virus's rapid evolution, which has the greatest recorded biological mutation rate known to science. This is due to the unstable nature of reverse transcriptase, key for viral replication but lacking proofreading capabilities, short generation times, and recombination [5]. This leads to widespread viral diversity both within and between hosts, making it challenging for the immune system to remove the virus and researchers to create treatments and vaccines to combat it. Although it is relatively simple to create a vaccine against one strain of HIV-1, the vaccination will only be effective against that one strain due to the hundreds of thousands of distinct strains. HIV-1 has developed strategies to evade the immune system due to its rapid mutation rate [6].

The main way that HIV-1 evades the immune system is by heavily glycosylating its Envelope Protein (Env). Env found on the virion envelope's surface enables HIV-1's entry into target immune cells by attaching to its major host receptor CD4. Host antibodies target Env because it is the only viral protein that is visible on the surface. Approximately half of its mass is made up of host-derived glycans; HIV-1 Env is one of the most densely glycosylated proteins known and evolved several glycan sites to evade antibody neutralization [7]. Since the host-derived glycans make Env seem less like a foreign invader and are harder for antibodies to recognize. They form a shield around it that inhibits antibody identification and binding. In certain CD4+T-cells, HIV-1 remains latent and virtually undetectable to the immune system, but it can re-emerge from these cells at any point in the future. HIV-1 also swiftly integrates itself into host chromosomes [8].

While latency is established during the initial weeks of infection, HIV-1 is only eradicable for a comparatively short time. This suggests that vaccine candidates must elicit an immune response that can eradicate the virus in the first few weeks before latency develops. This has proven challenging, especially for T-cell-based vaccinations, because the virus has already seeded itself in cells all over the body by the time a T-cell response takes to control it [9]. The virus must actually have infected cells in order for the T-cell response to occur. Before immunity takes over and eradicates the illness, there must be a specific amount of infection. The virus has already seeded itself in numerous cells throughout the body by the time a T-cell response takes to effectively control it, and it is virtually too late [10].

The transition to broadly neutralizing antibodies

Due to the difficulties in developing T-cell and conventional antibody vaccines against HIV-1, research has shifted to Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies (bnAbs). The naturally occurring antibodies known as bnAbs are capable of neutralizing a wide variety of viral types. Unlike non-bnAbs, which target different epitopes, bnAbs target conserved portions of Env, which remain constant across strains and do not alter when the virus mutates. This allows them to overcome the variability barrier [11]. Research has investigated that between 10 and 25% of those with HIV-1 who are chronically infected develop bnAbs. Nevertheless, they only make up a small portion of a person's HIV-1 antibody response. According to trials, bnAbs can assist in treating an existing infection and stop HIV-1 from acquiring bnAb-sensitive viruses when given passively. But just like ART, protection is only temporary, and regular administration of bnAbs is required. When an infected person is exposed to several strains of the virus, antibodies are developed to recognize structures shared by different strains of HIV-1 [12].

To research and produce the immunogens, a wide range of technologies and methodologies are required. Single-cell methods are used to "mine" bnAbs from sick people. Crystallography and cryoEM are then used to determine the structure of the antibodies in relation to Env. Computational and artificial intelligence techniques use these structures to propose structures for the virus shape that the antibodies attach to. The germline targeting strategy employs a series of immunogens that can generate HIV-1-specific bnAbs [13]. Using yeast or mammalian display, large libraries of suggested designs are created, and the forms that bnAbs recognize the best are selected as immunogens. Since non-human primates do not manufacture the same antibodies as humans, the selected immunogens are tested in animal models, including non-human primates and knock-in mice, which are mice altered using CRISPR-Cas9 to create human antibodies [14].

Protein subunit vaccine: vax trials and neutralizing antibody hunt

Protein subunit vaccines were the first HIV vaccine candidates to go into clinical investigations. Both attenuated and inactivated vaccines had been investigated in Non-Human Primates (NHPs) prior to the invention of protein subunit vaccines. Compared to other vaccination methods like viral vectors and DNA plasmids, protein subunits provide the benefit of substantial expertise pertaining to vaccine design and production, as an effective protein subunit vaccine has been created for influenza A and B viruses [15]. The HIV envelope serves as the basis for HIV protein subunit vaccines. Early HIV vaccine clinical trials investigated Recombinant gp160 (rgp160) and Recombinant gp120 (rgp120) monomers as immunogens. The rgp160 vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies against the homologous vaccine strain but not against heterologous strains, and it caused minimal antibody responses overall. A rgp120 vaccine demonstrated somewhat increased immunogenicity and a neutralizing effect against a heterologous strain in a phase-I investigation [16].

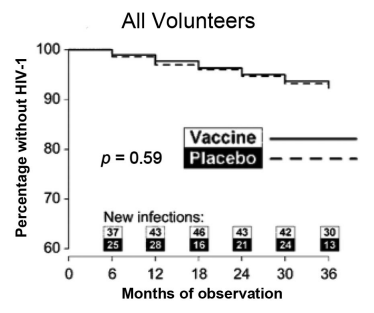

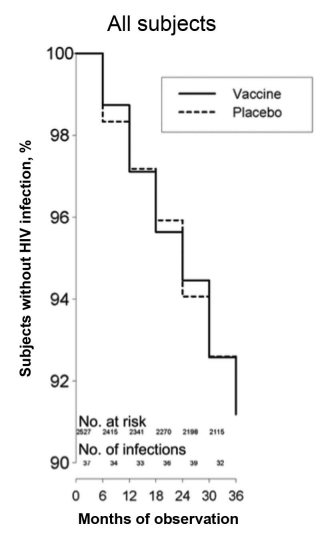

A similar rgp120 immunogen made from a different strain of HIV-1 (MN) was found to be safe and immunogenic in humans, and it protected chimpanzees against heterologous strains. The AIDSVAX vaccinations used in the VAX004 and VAX003 studies were based on this immunogen. The rgp120 immunogens from strains MN and GNE8 were present in AIDSVAX B/B. AIDSVAX B/E, which included rgp120 immunogens from strains MN and A244, was assessed [17]. MN was a laboratory-modified strain, while GNE8 and A244 were primary isolates. Experimental evidence that laboratory-adapted viruses differ from primary isolates in several respects, such as using the CXCR4 coreceptor instead of the CCR5 and being more sensitive to neutralization, led to the inclusion of the primary isolates [18]. Neither experiment showed efficacy against infection acquisition (fig. 1 and fig. 2).

Fig. 1: The VAX004 kaplan-meier graph depicts the time to HIV-1 infection [18]

Fig. 2: The VAX003 kaplan-meier graph depicts the time to HIV-1 infection [18]

These investigations demonstrated that in a high-risk group, rgp120 monomers did not prevent HIV infection and only produced weak neutralizing antibody responses. The goal of current HIV protein component immunogens is to better mimic the native viral envelope to elicit better neutralizing antibody responses. While lacking the conformational features of the native envelope trimer, the rgp120 monomers used in the VAX trials have the advantage of being relatively easy to assemble. The CD4-binding site is one of many crucial epitopes that neutralizing antibodies target [19]. These epitopes are conformational in nature and heavily rely on the envelope trimer's three-dimensional shape. Recombinant trimers have been stabilized using various techniques to make them acceptable for large-scale manufacture. The majority of recombinant trimers examined to date have only shown slightly improved immunogenicity when compared to monomers. Glycosylation is another characteristic of the native viral envelope that might be crucial for the production of neutralizing antibodies [20].

Certain human cell lines must create immunogens in order for protein subunits to be properly glycosylated. These cell lines were not used in the production of the AIDSVAX vaccines. A stable envelope trimer that more nearly mimics the glycosylation and other antigenic characteristics of the natural envelope trimer was recently created. For example, it has been demonstrated that this trimer produces better neutralizing antibody responses in guinea pigs than monomers. Phase-I trials are likely to begin within the next year or two, and clinical-grade material is already being produced [21]. The discovery of compelling bnAbs against HIV-1 has been a recent significant development with significant ramifications for vaccine design. For instance, 10E8 neutralizes 98% of studied viruses, VRC-01, which has a breadth of about 90%, and PG9 and PG16, which have a breadth of about 80%. Although they do not achieve the same level of neutralizing breadth, some bnAbs have been found to be more than ten times as effective as PG9, PG16, and VRC01 [22].

Another bnAb, VRC07, has likewise had its efficacy and breadth further increased through the use of structural modification techniques. Several traits are shared by the bnAbs that have been characterized thus far. The membrane-proximal exterior section of gp41, the glycan-V3 site on gp120, the first and second variable regions (V1/V2) on gp120, or the CD4 binding site on gp120 are the four different places on the viral envelope spike that they all recognize. Furthermore, all bnAbs have peculiar characteristics, such as a large somatic mutation, an unusually lengthy complementarity-determining region, or both [23]. Passive immunization with bnAbs has been demonstrated to offer NHPs strong defense against infection by the chimeric Simian/Human Immunodeficiency Virus (SHIV). It is likely that new approaches will be needed to create vaccinations that can stimulate bnAbs against HIV-1. Another barrier to the production of bnAbs is the fact that some of them are polyreactive to host antigens. Only 10-30% of people develop bnAbs after two to four years, even in the case of chronic HIV-1 infection [24].

Because the immune system may either prevent the production of these antibodies or fail to make them without considerable somatic mutation, it is uncertain whether standard immunization approaches may induce bnAbs. A new strategy called B-cell-lineage vaccine design seeks to improve the elicitation of bnAbs by encouraging antibody responses along the desired B-cell maturation route [25]. Finding out which B-cells produce bnAbs and analyzing how those cells differ from their naive B-cell progenitor are the first steps in creating a B-cell-lineage vaccine. Vaccine immunogens would then be developed to suitably direct the development of B-cells. Interestingly, the antigen that stimulates the mature B-cell may differ from the one that first activated the naive B-cell [26]. Similarly, different antigens may be required at each stage of B-cell maturation, resulting in a vaccination schedule that includes several different immunogens. The recently reported evolution of the bnAb CH103 in a chronically infected individual may serve as a roadmap for developing a vaccination based on the B-cell-lineage approach. Another possible tactic to increase the possibility of activating bnAbs is to employ adjuvants to activate the enzymes that regulate somatic mutation [27].

The cellular immunological response to viral vector vaccines

The cellular immunity is crucial to the immune response against HIV infection. This was demonstrated in rhesus macaques infected with the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), where the depletion of CD8+T-cells caused by chronically infected macaques treated with an anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody resulted in a marked rise in viremia and disease development [28]. Research on elite controllers of HIV-1 infection has also shown the importance of cellular immunity in controlling viremia. HLA-B*57, HLA-B*27, and HLA-B*5701 are the specific Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) alleles that have been associated with the capacity to control viral replication. Indeed, differences in HLA-B*27-restricted CD8+T-cells between individuals with and without disease have been reported recently [29]. Since Natural Killer (NK) cells may also play a role in the HLA-mediated control of viral replication, examining the NK cell response may also be essential in assessing the immunogenicity of vaccine candidates. One technique for triggering a cellular immune response by vaccination is the use of recombinant viral vectors, in which a virus is altered to produce a desired gene [30].

Replication-incompetent or poorly competent viruses that replicate in mammalian cells or viruses that have been rendered such by gene deletion or in vitro adaptation (adenoviruses, Modified Vaccinia Ankara) are among the viral vectors that have been examined as HIV vaccine candidates. The Step and HVTN 503/Phambili investigations employed Recombinant Adenovirus Serotype 5 (rAd5) as the vector because it has been demonstrated to be highly immunogenic. It is the first efficacy trial to evaluate an HIV vaccine designed to elicit T-cell responses [31]. Step and HVTN 503/Phambili evaluated the same immunization, a rAd5 vector carrying genes for Gag, Pol, and Nef from clade B viruses. The trial was stopped at the first interim analysis when it met predefined efficacy futility boundaries. Remarkably, during long-term follow-up, male vaccinees who were both uncircumcised and Ad5 seropositive had a statistically significant increased risk of HIV infection, which declined over time (fig. 3) [32].

Fig. 3: The Kaplan-Meier graph from the Step investigation's extended follow-up (p = 0.02 for the first 18 mo) demonstrates the time to HIV-1 infection in Ad5 (seropositive, uncircumcised) men [32]

The rAd5 vaccination used in Step elicited modest CD8+T-cell responses from the majority of vaccinees, although these responses were limited to targeting a few specific epitopes. However, in a sample of infected individuals with protective HLA alleles, the mean viral load gradually dropped in vaccination recipients compared to placebo recipients [33]. A second experiment, known as HVTN 503/Phambili, was conducted in South Africa, primarily on heterosexuals who were deemed low-risk. Because of the high prevalence of HIV infection in Step, participation was halted after only 801 of the 3000 participants were enrolled. Vaccinees had a greater rate of HIV infections than placebo users; however, the difference was not statistically significant [34]. Vectors based on different adenovirus serotypes with lower seroprevalence rates than Ad5 have been assessed in light of Step's findings. Phase-I tests revealed that recombinant vectors utilizing Ad26 and Ad35 were immunogenic. Several poxvirus vectors have also been assessed in addition to adenovirus vectors. Phase I and II trials revealed that a canarypox vector had reduced immunogenicity. Several early-phase trials are now being conducted to assess NYVAC and MVA, which seem to be more immunogenic than canarypox [35].

Investigations in animal models using combinations of MVA, rAd26, and rAd35 have generally demonstrated improved cellular immune responses and increased protection against infection when compared to similar regimens. Although clinical trials have only looked at HIV vaccines based on viral vectors that are either incapable or have low replication capabilities, replication-competent vectors may be more immunogenic and are now being evaluated [36]. The distinction between effector memory and central memory CD8+T-cells has been the subject of additional study on vaccinations intended to induce a CD8+T-cell response. Although HIV vaccine candidates have frequently elicited a central memory T-cell response, it has been proposed that an effector memory T-cell response may be more capable of lowering viremia following infection. Effector memory T-cell responses are primarily caused by persistent infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections [37]. In a recent study, rhesus macaques were vaccinated against CMV and then challenged with SIVmac239, a highly pathogenic variant of SIV. The majority of macaques that got the CMV-vectored vaccine demonstrated notable control of viremia following multiple mucosal challenges, in contrast to none of the macaques that received a DNA/rAd5 vaccine [38].

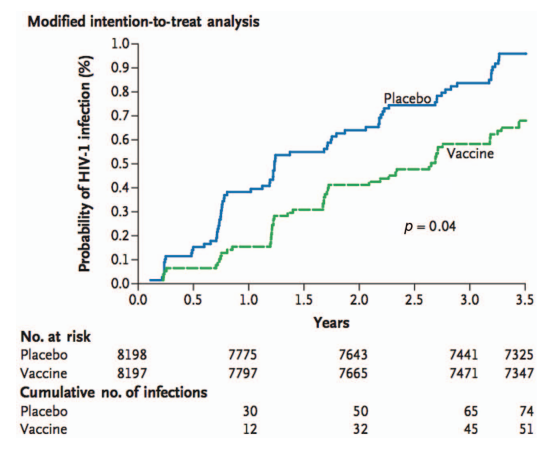

Heterologous prime-boost regimens: non-neutralizing antibody and RV144

RV144 utilized the heterologous prime-boost therapy strategy, which involved priming a canarypox viral vector that expressed Env, Gag, and Pol (ALVAC) followed by an AIDSVAX B/E boost. In Thailand, low-risk heterosexual men and women were the main recipients of the vaccinations [39]. According to the modified intention-to-treat analysis, the vaccine's effectiveness against infection acquisition was 31.2% (fig. 4). There was no discernible impact on CD4+T-cell counts or viral load in vaccination recipients who did contract the infection. According to a later analysis, there was a substantial correlation between vaccine efficacy and risk. Comparatively, to 5% of those in the high-risk group, 68% of those who maintained low or medium risk during the investigation saw efficacy [40]. Furthermore, efficacy seemed to peak in the first 12 mo before sharply declining after that. The investigation of immunological correlates of risk revealed that IgG binding to V1/V2 was associated with a decreased risk of infection, while plasma IgA directed against Env neutralized this protection. Perhaps this latter effect was brought on by IgA's disruption of IgG effector activities, which has been observed in the setting of both infection and cancer [41].

Fig. 4: The kaplan-meier graph from RV144 illustrates the time to HIV-1 infection in the modified intention-to-treat evaluation [40]

IgG-mediated Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC) effectors may be inhibited by specific Env-directed IgA antibodies that were recovered from RV144 vaccinees. Further investigations of immunogenicity showed that the RV144 regimen evoked a CD4+T-cell response against V2, but only a moderate T-cell response and a minor neutralizing antibody response [42]. An examination of breakthrough viral strains also demonstrated the potential impact of the immune response against V2. The V2 region of Env contains both of these amino acids. Since the immunological correlates investigation of RV144 did not identify neutralizing antibodies or cellular immune responses linked to a lower risk, it is possible that non-neutralizing antibodies against V1/V2 contribute to protection [43]. Following the results of RV144, non-neutralizing antibodies against V2 were found to correlate with protection against a demanding SIV challenge in rhesus macaques vaccinated with DNA/MVA, rAd26/MVA, or MVA/rAd26 regimens. Because effector activities like ADCC occur in conjunction with innate immune system cells, non-neutralizing antibodies against V1/V2 may offer protection [44].

HVTN 505 and DNA vaccinations

A plasmid encoding a desired protein makes up DNA vaccines. The same genes that are delivered by a live vectored vaccination can also be delivered by a DNA vaccine without the development of immunity against the vector, which could prevent the insert from being expressed. When tested in humans for several viruses (including HIV), early candidate DNA vaccines were illustrated to be insufficiently immunogenic [45]. Techniques like electroporation and the use of molecular adjuvants have been employed in later-generation DNA vaccines to increase immunogenicity. A heterologous DNA/rAd5 regimen performed better than a homologous rAd5/rAd5 regimen in a phase-I trial in terms of CD4+T-cell responses and CD8+T-cell interleukin 2 production [46]. In another phase-I investigation, a DNA/rAd5 regimen significantly improved T-cell and antibody responses compared to either DNA or rAd5 alone. Additionally, a DNA/MVA regimen was demonstrated to improve the T-cell immune response in comparison to MVA alone. In the United States, the most recent HIV vaccine efficacy trial (HVTN 505, a phase IIb research) evaluated a DNA prime followed by a rAd5-vectored boost in MSM [47].

Gag, Pol, Nef, and Env were expressed by the DNA plasmid, while Gag, Pol, and Env were expressed by the rAd5 boost. In contrast, Env was not expressed by the rAd5 vaccine utilized in Step. The inclusion criteria were limited to men who were circumcised and Ad5 seronegative to mitigate the potential for elevated HIV infection risk associated with the use of the rAd5 vector in Step [48]. The 505 investigations, which had enrolled 2504 patients, were terminated due to lack of efficacy in 2013, according to the HVTN, because both the HIV acquisition and the post-acquisition viral load setpoint futility criteria were satisfied. HIV infection rates among vaccinees and placebo recipients were not statistically different at the time the trial was stopped, with 27 HIV infections among vaccine recipients and 21 HIV infections among placebo recipients. The HVTN 505 trial participants will be continuously monitored for further research outcomes [49].

Perspectives from the transmission incident

A single person harbors a quasi-species of virus throughout a prolonged infection. However, research on sexual transmission has demonstrated that just one strain of the virus is spread in about 80% of cases. Several investigations have discovered that founder viruses, another name for transmitted viruses, seem to possess specific characteristics. In a preliminary investigation of three mother-infant pairs, the viral sequences of the infants were less diverse than those of the mothers, and the V3 virus had a conserved N-linked glycosylation site [50]. Compared to viruses detected during chronic infection, transmitted clade C viruses exhibited shorter, less glycosylated envelope variable loops and were more neutralization-susceptible. Furthermore, transmitted clade C viruses can have a significantly lower representation of the glycan at amino acid position 332 than viruses that are present during chronic infection. Variants observed early in the donor's infection course appeared to be more closely connected to transmitted strains than to those circulating in the donor near the time of transmission [51].

The number of viruses that spread appears to depend on the viral lineage and the mode of transmission, and their distinct traits make the previously indicated conclusions more difficult to understand. In a cohort of MSM, only 46% of transmitted viruses seemed to originate from a single version, but in about 80% of heterosexual transmission events, only one variety is transmitted. In rhesus macaques, intravenous inoculation of SIV resulted in a more complicated founder population than intravaginal injection. In a study of a small heterosexual African cohort, it was discovered that in the vast majority of cases, only one strain of the virus was transferred [52]. While genital infections were associated with a higher transmission of virus strains, limiting the genetic variety of the infecting virus may need an intact mucosal barrier. Although the specific traits of clade C viruses were also present in clade a viruses, neither clade B nor clade D viruses exhibited these traits. Transmitted viruses in all clades and transmission methods cannot yet be identified by a single viral signature. If these variants are significantly different from other HIV strains, future vaccines may be designed to target transmitted viruses specifically [53].

Interpose of mosaic sequence

The diversity of HIV poses a significant obstacle to the eventual goal of creating a global vaccine. In an attempt to address this problem, mosaic sequences have been developed for use in viral vector vaccines. These sequences were generated by computer algorithms to maximize the coverage of possible T-cell epitopes from worldwide HIV-1 strains. T-cell epitopes are amino acid sequences that are recognized by CD8+T lymphocytes and that HLA class I molecules present on the surface of infected cells [54]. Mosaic sequences can stimulate immune responses capable of recognizing viruses from different clades by maximizing the representation of global viral strains. Investigations on rhesus macaques demonstrated that mosaic sequences improve the breadth and depth of the T-cell response compared to consensus or natural sequences. However, the immunological response that mosaic sequences will elicit has not yet been tested on humans. Interestingly, phase-I clinical trials using mosaic sequence inserts will be conducted for vaccines vectored by orthopox and adenovirus [55].

Vectored immunoprophylaxis

The method called vectored immunoprophylaxis delivers bnAbs via a viral vector containing immunoglobulin gene inserts. Performing this, the difficult procedure of producing these rare antibodies using immunogens is avoided. In a study of this approach, genes encoding a bnAb against HIV-1 were inserted into the vector, an Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) [56]. Since AAV is not known to cause disease and has been designed to not integrate into the human genome, it has been thoroughly investigated as a possible gene therapy vector. When a humanized mouse was administered an AAV vector containing human immunoglobulin genes intramuscularly, it produced bnAb consistently and protected against high-dose intravenous HIV challenges. The AAV vector has the potential for long-lasting protection and is comparatively cheap to create [57].

Future prospect

The mosaic sequence inserts, which may elicit a more thorough immune response than native HIV-1 sequence inserts, will also be investigated in subsequent experiments. A new recombinant glycoprotein trimer will be evaluated as a protein boost and may elicit a higher neutralizing antibody response than rgp120 monomers. Future research assessing comparable regimens may include longer immunization schedules, especially to promote antibody responses, to extend the period of protection, as the protection explored in RV144 was only temporary [58]. An important finding for the creation of an HIV vaccine is the identification of potent bnAbs against HIV-1. Novel strategies, such as vectored immunoprophylaxis and B-cell-lineage vaccine design, are being investigated to generate or induce these antibodies. The HIV vaccine efficacy investigations that have been carried out thus far have demonstrated that a safe and effective HIV vaccine is achievable and have significantly advanced our knowledge of the development process for such a vaccine. Future progress will depend on an ongoing connection between preclinical research findings and properly planned out, effectively carried out clinical trials [59].

CONCLUSION

All four HIV vaccine hypotheses have produced useful evidence, even if only one has demonstrated potency. For a short time, a prime-boost approach that combined a canarypox vector prime with a rgp120 boost (RV144) displayed a moderate level of effectiveness (31.2%). Genetic features in the V2 region were also connected to vaccine efficacy in an investigation of new virus strains. Interestingly, vaccination is anticipated to influence the sequencing of breakthrough HIV strains in Step and VAX003. This implies that there may have been some selective pressure on transmitted viruses from the vaccinations employed in those experiments. In a low-risk heterosexual population, RV144 showed efficacy; however, it is uncertain how population risk variables affect the regimen's eventual success in RV144. As a result, a proposed vaccine given to this group might only need to block one strain of the virus, which might increase its efficacy. These investigations will evaluate viral-vector prime and protein-subunit boost regimens in addition to introducing novel vectors, inserts, and protein subunits. Vectors such as Ad26, MVA, and NYVAC will be investigated both individually and in combination due to their high immunogenicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is thankful to the Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology, Nagpur, for motivating the research work and writing the article. The author is also thankful to the Faculty of Science, Janata Junior College, Nagbhid, for encouraging research work.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The author is solely responsible for conducting the research and writing of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Alt FW, Zhang Y, Meng FL, Guo C, Schwer B. Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell. 2013;152(3):417-29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.007, PMID 23374339.

Baden LR, Blattner WA, Morgan C, Huang Y, Defawe OD, Sobieszczyk ME. Timing of plasmid cytokine (IL-2/Ig) administration affects HIV-1 vaccine immunogenicity in HIV-seronegative subjects. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(10):1541-9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir615, PMID 21940420.

Baden LR, Walsh SR, Seaman MS, Tucker RP, Krause KH, Patel A. First-in-human evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 HIV-1 Env vaccine (IPCAVD 001). J Infect Dis. 2013;207(2):240-7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis670, PMID 23125444.

Balazs AB, Chen J, Hong CM, Rao DS, Yang L, Baltimore D. Antibody-based protection against HIV infection by vectored immunoprophylaxis. Nature. 2011;481(7379):81-4. doi: 10.1038/nature10660, PMID 22139420.

Ramteke AS. Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus, effective treatment and prevention strategy. Int J Pharm Sci. 2024;2:703-17.

Barouch DH, Liu J, Li H, Maxfield LF, Abbink P, Lynch DM. Vaccine protection against acquisition of neutralization-resistant SIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2012;482(7383):89-93. doi: 10.1038/nature10766, PMID 22217938.

Barouch DH, O’Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF. Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat Med. 2010;16(3):319-23. doi: 10.1038/nm.2089, PMID 20173752.

Beddows S, Franti M, Dey AK, Kirschner M, Iyer SP, Fisch DC. A comparative immunogenicity study in rabbits of disulfide-stabilized, proteolytically cleaved, soluble trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp140, trimeric cleavage-defective gp140 and monomeric gp120. Virology. 2007;360(2):329-40. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.032, PMID 17126869.

Berman PW, Murthy KK, Wrin T, Vennari JC, Cobb EK, Eastman DJ. Protection of MN-rgp120-immunized chimpanzees from heterologous infection with a primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(1):52-9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.52, PMID 8537682.

Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the step study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9653):1881-93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3, PMID 19012954.

Burton DR, Poignard P, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science. 2012;337(6091):183-6. doi: 10.1126/science.1225416, PMID 22798606.

Carrington M, O’Brien SJ. The influence of HLA genotype on AIDS. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:535-51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152346, PMID 12525683.

Chen H, Ndhlovu ZM, Liu D, Porter LC, Fang JW, Darko S. TCR clonotypes modulate the protective effect of HLA class I molecules in HIV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(7):691-700. doi: 10.1038/ni.2342, PMID 22683743.

Chohan B, Lang D, Sagar M, Korber B, Lavreys L, Richardson B. Selection for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycosylation variants with shorter V1–V2 loop sequences occurs during transmission of certain genetic subtypes and may impact viral RNA levels. J Virol. 2005;79(10):6528-31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6528-6531.2005, PMID 15858037.

Cox KS, Clair JH, Prokop MT, Sykes KJ, Dubey SA, Shiver JW. DNA gag/adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) gag and Ad5 gag/Ad5 gag vaccines induce distinct T-cell response profiles. J Virol. 2008;82(16):8161-71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00620-08, PMID 18524823.

Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Bibollet Ruche F, Mokili JL, Muldoon M, Denham SA. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science. 2004;303(5666):2019-22. doi: 10.1126/science.1093137, PMID 15044802.

De Souza MS, Ratto Kim S, Chuenarom W, Schuetz A, Chantakulkij S, Nuntapinit B. The thai phase III trial (RV144) vaccine regimen induces T cell responses that preferentially target epitopes within the V2 region of HIV-1 envelope. J Immunol. 2012;188(10):5166-76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102756, PMID 22529301.

Dolin R, Graham BS, Greenberg SB, Tacket CO, Belshe RB, Midthun K. The safety and immunogenicity of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) recombinant gp160 candidate vaccine in humans. NIAID AIDS Vaccine Clinical Trials Network Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(2):119-27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-2-119, PMID 1984386.

Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Shiver JW, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:617-48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.617, PMID 9143702.

Excler JL, Parks CL, Ackland J, Rees H, Gust ID, Koff WC. Replicating viral vectors as HIV vaccines: summary report from the IAVI-sponsored satellite symposium at the AIDS vaccine 2009 conference. Biologicals. 2010;38(4):511-21. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2010.03.005, PMID 20537552.

Fadda L, O’Connor GM, Kumar S, Piechocka Trocha A, Gardiner CM, Carrington M. Common HIV-1 peptide variants mediate differential binding of KIR3DL1 to HLA-Bw4 molecules. J Virol. 2011;85(12):5970-4. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00412-11, PMID 21471246.

Ferraro B, Morrow MP, Hutnick NA, Shin TH, Lucke CE, Weiner DB. Clinical applications of DNA vaccines: current progress. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(3):296-302. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir334, PMID 21765081.

Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, Bhattacharya T, Yusim K, Funkhouser R. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat Med. 2007;13(1):100-6. doi: 10.1038/nm1461, PMID 17187074.

Flynn NM, Forthal DN, Harro CD, Judson FN, Mayer KH, Para MF. Placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine to prevent HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(5):654-65. doi: 10.1086/428404, PMID 15688278.

Frost SD, Liu Y, Pond SL, Chappey C, Wrin T, Petropoulos CJ. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope variation and neutralizing antibody responses during transmission of HIV-1 subtype B. J Virol. 2005;79(10):6523-7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6523-6527.2005, PMID 15858036.

Gilbert P, Wang M, Wrin T, Petropoulos C, Gurwith M, Sinangil F. Magnitude and breadth of a nonprotective neutralizing antibody response in an efficacy trial of a candidate HIV-1 gp120 vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(4):595-605. doi: 10.1086/654816, PMID 20608874.

Girard MP, Osmanov S, Assossou OM, Kieny MP. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) immunopathogenesis and vaccine development: a review. Vaccine. 2011;29(37):6191-218. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.085, PMID 21718747.

Goepfert PA, Elizaga ML, Sato A, Qin L, Cardinali M, Hay CM. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity testing of DNA and recombinant modified vaccinia Ankara vaccines expressing HIV-1 virus-like particles. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(5):610-9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq105, PMID 21282192.

Goepfert PA, Horton H, McElrath MJ, Gurunathan S, Ferrari G, Tomaras GD. High-dose recombinant canarypox vaccine expressing HIV-1 protein, in seronegative human subjects. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(7):1249-59. doi: 10.1086/432915, PMID 16136469.

Gomez CE, Perdiguero B, Garcia Arriaza J, Esteban M. Poxvirus vectors as HIV/AIDS vaccines in humans. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(9):1192-207. doi: 10.4161/hv.20778, PMID 22906946.

Gorny MK, Stamatatos L, Volsky B, Revesz K, Williams C, Wang XH. Identification of a new quaternary neutralizing epitope on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virus particles. J Virol. 2005;79(8):5232-7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5232-5237.2005, PMID 15795308.

Gottlieb GS, Heath L, Nickle DC, Wong KG, Leach SE, Jacobs B. HIV-1 variation before seroconversion in men who have sex with men: analysis of acute/early HIV infection in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(7):1011-5. doi: 10.1086/529206, PMID 18419538.

Greenier JL, Miller CJ, Lu D, Dailey PJ, Lu FX, Kunstman KJ. Route of simian immunodeficiency virus inoculation determines the complexity but not the identity of viral variant populations that infect rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3753-65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3753-3765.2001, PMID 11264364.

Griffiss JM, Goroff DK. IgA blocks IgM and IgG-initiated immune lysis by separate molecular mechanisms. J Immunol. 1983;130(6):2882-5. PMID 6854021.

Grundner C, Li Y, Louder M, Mascola J, Yang X, Sodroski J. Analysis of the neutralizing antibody response elicited in rabbits by repeated inoculation with trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. Virology. 2005;331(1):33-46. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.022, PMID 15582651.

Hansen SG, Ford JC, Lewis MS, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Coyne Johnson L. Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T-cell vaccine. Nature. 2011;473(7348):523-7. doi: 10.1038/nature10003, PMID 21562493.

Hemelaar J. The origin and diversity of the HIV-1 pandemic. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(3):182-92. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.12.001, PMID 22240486.

Hessell AJ, Poignard P, Hunter M, Hangartner L, Tehrani DM, Bleeker WK. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal SHIV challenge in macaques. Nat Med. 2009;15(8):951-4. doi: 10.1038/nm.1974, PMID 19525965.

Huang J, Ofek G, Laub L, Louder MK, Doria Rose NA, Longo NS. Broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by a gp41-specific human antibody. Nature. 2012;491(7424):406-12. doi: 10.1038/nature11544, PMID 23151583.

Jarvis GA, Griffiss JM. Human IgA1 blockade of IgG-initiated lysis of Neisseria meningitidis is a function of antigen-binding fragment binding to the polysaccharide capsule. J Immunol. 1991;147(6):1962-7. PMID 1909736.

Johnston MI, Fauci AS. HIV vaccine development-improving on natural immunity. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):873-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1107621, PMID 21899447.

Keefer MC, Graham BS, Belshe RB, Schwartz D, Corey L, Bolognesi DP. Studies of high doses of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 recombinant glycoprotein 160 candidate vaccine in HIV type 1-seronegative humans. The AIDS Vaccine Clinical Trials Network AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10(12):1713-23. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1713, PMID 7888231.

Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar Gonzalez JF, Decker JM, Pham KT, Salazar MG. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(21):7552-7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105, PMID 18490657.

Kim M, Qiao ZS, Montefiori DC, Haynes BF, Reinherz EL, Liao HX. Comparison of HIV type 1 ADA gp120 monomers versus gp140 trimers as immunogens for the induction of neutralizing antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2005;21(1):58-67. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.58, PMID 15665645.

Korber B, Gaschen B, Yusim K, Thakallapally R, Kesmir C, Detours V. Evolutionary and immunological implications of contemporary HIV-1 variation. Br Med Bull. 2001;58:19-42. doi: 10.1093/bmb/58.1.19, PMID 11714622.

Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature. 2013;496(7446):469-76. doi: 10.1038/nature12053, PMID 23552890.

MacGregor RR, Boyer JD, Ugen KE, Lacy KE, Gluckman SJ, Bagarazzi ML. First human trial of a DNA-based vaccine for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: safety and host response. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(1):92-100. doi: 10.1086/515613, PMID 9652427.

Mathew GD, Qualtiere LF, Neel HB, Pearson GR. IgA antibody, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and prognosis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1981;27(2):175-80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910270208, PMID 6169655.

McElrath MJ, Haynes BF. Induction of immunity to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 by vaccination. Immunity. 2010;33(4):542-54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.011, PMID 21029964.

Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Huang Y, Ahmed H, Gilbert P, de Souza MS. Magnitude and breadth of the neutralizing antibody response in the RV144 and Vax003 HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(3):431-41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis367, PMID 22634875.

Moore PL, Gray ES, Sheward D, Madiga M, Ranchobe N, Lai Z. Potent and broad neutralization of HIV-1 subtype C by plasma antibodies targeting a quaternary epitope including residues in the V2 loop. J Virol. 2011;85(7):3128-41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02658-10, PMID 21270156.

Moore PL, Gray ES, Wibmer CK, Bhiman JN, Nonyane M, Sheward DJ. Evolution of an HIV glycan-dependent broadly neutralizing antibody epitope through immune escape. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1688-92. doi: 10.1038/nm.2985, PMID 23086475.

Pantophlet R, Burton DR. GP120: target for neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:739-69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090557, PMID 16551265.

Santra S, Liao HX, Zhang R, Muldoon M, Watson S, Fischer W. Mosaic vaccines elicit CD8+T lymphocyte responses that confer enhanced immune coverage of diverse HIV strains in monkeys. Nat Med. 2010;16(3):324-8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2108, PMID 20173754.

Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, Sasseville VG, Simon MA, Lifton MA. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283(5403):857-60. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857, PMID 9933172.

Schwartz DH, Gorse G, Clements ML, Belshe R, Izu A, Duliege AM. Induction of HIV-1-neutralising and syncytium-inhibiting antibodies in uninfected recipients of HIV-1IIIB rgp120 subunit vaccine. Lancet. 1993;342(8863):69-73. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91283-r, PMID 8100910.

Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011;477(7365):466-70. doi: 10.1038/nature10373, PMID 21849977.

Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326(5950):285-9. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746, PMID 19729618.

Wolinsky SM, Wike CM, Korber BT, Hutto C, Parks WP, Rosenblum LL. Selective transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 variants from mothers to infants. Science. 1992;255(5048):1134-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1546316, PMID 1546316.