Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 6, 1-6Review Article

ROLE OF PLANT-BASED FLAVONOIDS AS DRUG CANDIDATES FOR INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE-A SHORT REVIEW

SAMRITI FAUJDAR1, PRABHA HULLATTI1*, NABARUN MUKHOPADHYAY2, A. P. BASAVARAJAPPA3, SARASWATI PATEL4

1Department of Pharmacy, Banasthali Vidyapith, Rajasthan, India. 2Department of Chemical Sciences (Natural Products), National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER), Hyderabad, Telangana, India. 3Department of Pharmacology, Bapuji Pharmacy College, Davangere, Karnataka, India. 4Department of Pharmacology, Saveetha College of Pharmacy, Thandalam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Prabha Hullatti; *Email: prabha4vin@gmail.com

Received: 01 Feb 2025, Revised and Accepted: 25 Apr 2025

ABSTRACT

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a chronic disorder caused due to several factors. Out of these, inflammation is one of the major causative factors, and several inflammatory markers, like pro-inflammatory cytokines enzymes play an essential role in the progression and development of IBD. The existing therapies against IBD have severe adverse effects, and drug resistance can also occur. Hence, novel therapies against IBD need to be developed for the treatment and prevention of IBD. Natural products, specifically flavonoids, can be an excellent alternative to get better therapeutic efficacy. Hence, flavonoids can be utilized more bitterly as a drug candidate for IBD. Our review work mainly discussed the potential flavonoids and their role in treating IBD and also focussed on it by inhibiting inflammatory markers.

Keywords: Plant-based flavonoids, Phytoconstituents, Drugs, Inflammatory bowel disease

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i6.53851 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a complicated disease that is known for its prolonged conditions and occurrence throughout life. Nowadays, it is one of the major health concerns worldwide with less known pathophysiology and has become a burden for a larger population [1]. Usually, IBD is subdivided into two types: Ulcerative Colitis (UC) and Crohn’s Disease (CD); in the case of CD, the inflammation affects any portion of the intestine but is usually detected at the colon and ileum. UC is a general chronic inflammatory condition of the colon and rectum that mainly affects the submucosa and large intestinal mucosa [2, 3]. Generally, IBD is treated by easily available marketed anti-inflammatory drugs and monoclonal antibodies targeting Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α). Also, surgeries also used to be done to treat the same [4, 5]. Several research studies also suggested that a balanced diet can help to control and prevent IBD to a certain extent [6]. However, there are several disadvantages associated with existing therapies, as malignancy can happen due to TNF-α inhibitory agents, whereas intestinal perforation and hemorrhages can occur due to surgeries [7, 8]. So, nature-derived therapies can act as a potential alternative in this context and medicinal plants can be utilized as a lead for the same. Phenolics or polyphenolics are an important class of natural products which is generally identified by their aromatic or phenol ring structure. Further, they are classified into different sub-classes based on the phenolic rings present and the bonds that help to join those rings. Some important classes of phenolic compounds are flavonoids, lignans, stilbenes, hydroxycinnamic acids, etc., and usually, they act as anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory agents [9, 10]. Phenolics, specifically flavonoids, are predominantly abundant in several dietary sources like carrots, strawberries, berries, grapes, apples, and tea [11, 12]. There are different experimental models of IBD are available, which are generally utilized to evaluate the inhibitory potential of medicinal plants, plant extracts, fractions, and isolated compounds against IBD [13]. Generally, inflammations are induced in rodent IBD models in different ways like immune cell transfer, chemical agents etc. Several chemical agents like 2, 4,6-Trinitrobenzene Sulphonic Acid (TNBS), Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS), etc. used to administer to express the inflammatory conditions [13]. Hence, this review summarizes the potential mechanism behind the inhibition potential of flavonoids against IBD, highlighting different experimental preclinical models (in vitro and in vivo) of IBD and it may also help researchers in their future studies in the same.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present review work has been done by thoroughly assessing research articles retrieved from different online databases like Wiley online library, PubMed, Springer link, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, etc and in this work, different experimental animal models of IBD, evaluation of therapeutic potentials of flavonoids against IBD, clinical trials were covered. For this purpose, different keywords were utilized, like “Inflammatory bowel disease,” “Pathophysiology of IBD,” “Treatment for IBD,” “Medicinal plants,” “Phenolics, “Phenolics for IBD, ”and “Animal models for IBD” etc.

Review

Role of flavonoids as therapeutic agents against IBD

Flavonoids, an important class of natural product, majorly isolated from medicinal plants, play an important role in the treatment of IBD. One of the key contributors to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an imbalance in gut microbiota, which leads to excessive production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in intestinal epithelial cells. This ROS overload can damage tight junctions and increase intestinal epithelial permeability, ultimately compromising the intestinal barrier, triggering gastrointestinal inflammation, and contributing to the onset of IBD. Flavonoids, known for their potent antioxidant properties, help counteract these effects primarily by modulating the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway, inhibiting Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) activation, and regulating cell apoptosis [14, 15]. Several research works proved that different classes of flavonoids like flavones, is flavones, flavanols, flavanones, etc. showed moderate to significant inhibition against IBD in different experimental models. In this section, the protective role of different classes of plant-based flavonoids was discussed.

Flavonols

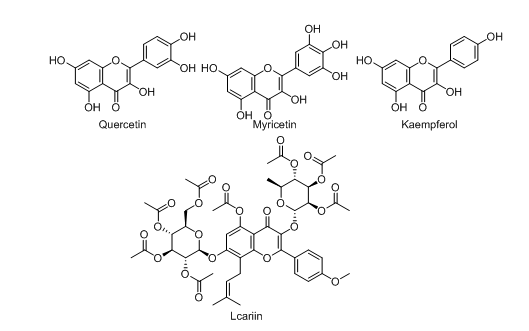

Quercetin

Quercetin (fig. 1.) is one of the most abundantly found flavonoids in nature and is present in numerous medicinal plants. It commonly exists in its glycosylated forms like quercitrin and rutoside [16]. An experimental rat model developed by Comalada M et al. proved that quercetin offered excellent protection against DSS-induced colitis [17]. Some in vitro and in vivo studies successfully proved the inhibition potential of pro-inflammatory cytokines by quercetin [18]. Dodda et al. explained that quercetin rectifies colon damage, controls the regulation activities of MDA (Malondialdehyde) and MPO (Myeloperoxidase), and also the glutathione content was increased by it in a TNBS-induced mouse colitis model [19]. This phytoconstituent also treats DSS-induced colon injury in rats by downregulating the colonic NOS activity, and intestinal oxidative stress was also improvised by reducing the expression of iNOS (Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase) protein [20]. Quercetin helps in the enhancement of particular protein expressions that are involved in the tight intestinal junctions, showing enhancement and reduction of intestinal integrity and intestinal permeability. It also protects the intestinal mucosal barrier [21-23].

Myricetin and kaempferol

Kaempferol (fig. 1) is an important flavonol class of phytocompound that helps in the effective treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. It was reported that kaempferol was successfully utilized as a supplement in a diet to mitigate DSS-induced colitis by decreasing several important inflammatory markers like iNOS, COX-2, IL-6 (Interleukin 6), TNF-α and it also helps to reduce the prostaglandin and nitric oxide levels in colonic mucosa [24].

Myricetin (fig. 1) is an important flavonol class of compound that is majorly isolated from the barks, leaves, and seeds of Myrica rubra [25, 26]. One research work stated that at the dose of 80 mg/kg this phytoconstituent effectively reduces ulcerative colitis and also plays an important role in the elevation of the levels of regulatory T cells [27].

Lcariin

Lcariin (fig. 1) is a flavonoid class of compounds (specifically 8-phenylflavonoid glycoside), and it is mainly isolated from the dried leaves and stems of Epimedium koreanum, Epimedium pubescens, etc. One research study showed that this phytocompound showed effective protection against DSS-induced enteritis in mice. While administered orally, Lcariin improves colitis-related pathological conditions and also disease progression will be postponed. It also decreases the pro-inflammatory mediators and isoforms of STAT enzymes in colonic tissues [28].

Fig. 1: Chemical structures of flavonols

Flavones

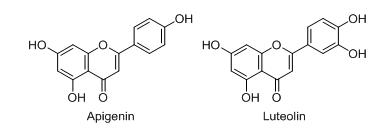

Apigenin

Apigenin (fig. 2) is a vital flavonoid that is majorly present in several fruits and vegetables, specifically in citrus fruits found in higher quantities [29, 30]. Several pieces of research demonstrated that apigenin can be useful for treating inflammatory bowel disease due to its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. Out of these, one interesting study stated that apigenin offered excellent protection against colitis in DSS-induced mice. This effect may come due to the inhibition of several inflammatory markers like MMP-3 (Matrix Metalloproteinase 3), iNOS, IL-1b (Interleukin 1 Beta), COX-2 (Cyclooxygenase 2), and TNF-α [31].

Luteolin

Luteolin (fig. 2), also known as 3’,4’,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone, is an important class of flavonoids that is majorly isolated from different plants like honeysuckle, garden bitter melon stems, celery, etc. [32, 33]. In several experimental models of IBD, it was observed that luteolin showed a potent protective effect. Out of these studies, an in vivo study done by Karrasch et al. stated that this phytoconstituent exhibited excellent protective action against colitis in IL-10 (Interleukin 10) deficient mice [34]. Nunes et al. proved that after treatment with luteolin, intracellular inflammatory signalling was modulated by the inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway in HT-29 colonic epithelial cells [35].

Fig. 2: Chemical structures of flavones

Flavanones

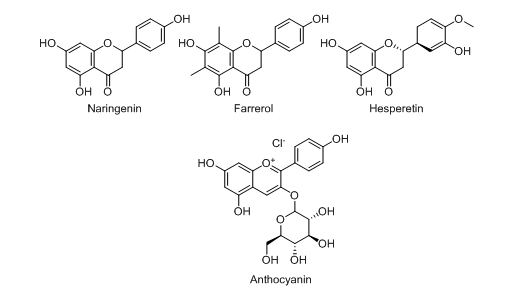

Naringenin

Naringenin (fig. 3), an aglycon part of naringin, is most commonly found in grapefruit and different research proved that it showed significant inhibition potential in different models of IBD [36-38]. A mouse model developed by Dou et al. exhibited that naringenin showed an excellent protective response against DSS-induced colitis. This protection may occurdue to the reduction of mRNA expressions of different factors responsible for inflammation like COX-2, IL-6, and TNF-α, etc [39]. It also reduced the expression of other inflammatory markers like Nitric Oxide (NO), prostaglandin, IL-1b, and IL-6 [40].

Farrerol

It is a 2, 3-dihydro flavonoid (fig. 3.) usually obtained from the Indian medicinal plant named rhododendron. One research study done by Ran et al. demonstrated that this phytoconstituent showed a significant reduction in several important inflammatory mediators like Il-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in RAW 264.7 cells [41]. It also can offer protection against TNBS-induced colitis in a mouse model [42].

Hesperetin

Hesperetin (fig. 3.) is an important flavanone glycoside, also known as 5,7,3ʹ-trihydroxy-4ʹ-methoxy flavanone is most commonly found in citrus fruits like oranges, limes, mandarins and lemons, etc. [43-45]. At the doses of 50 and 100 mg/kg, hesperetin showed significant improvement in the TNBS-induced colitis symptoms in the experimental rat models like recovering from macroscopic colon damage [46]. One more piece of research work proved that this phytoconstituent can successfully alleviate colitis by blockade of the intestinal epithelial necroptosis in the DSS-induced experimental mice model [47]. Hesperetin (at the dose of 100 mg/kg) also offered excellent protection against TNBS-induced colitis in the respective rat model [48].

Anthocyanin

Anthocyanin (fig. 3.) is a water-soluble flavonoid and is mainly obtained from fruits like red grapes, Murray, purple cabbage, blueberries, blackberries, etc. Basically, it is a coloured aglycone formed after hydrolyzing anthocyanins [49-51]. Wu et al. developed a TNBS-induced experimental mice modeland reported that at the doses of 40, 20, and 10 mg/kg, blueberry-derived anthocyanins exhibited a significant role in the same [52]. It was also observed that the anthocyanins extracted from bilberries and black rice showed potent efficacy in the relief of colitis [53, 54].

Isoflavones

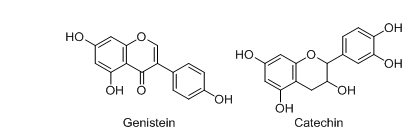

Genistein

Genistein (fig. 4) is an important class of isoflavone, which is also known as 4′, 5, 7-trihydroxy isoflavone is commonly obtained from soy milk, soy cheese, etc. [49, 50]. Zhang et al. observed that at the dose of 600 mg/kg, genistein reduced gut dysfunction and colonic inflammatory conditions in the DSS-induced colitis BALB/C mice model [55]. Abron et al. proved that at the dose of 10 mg/kg, this phytoconstituent effectively reduced the progression of ulcerative colitis in a DSS-induced experimental mice model [56].

Fig. 3: Chemical structures of flavanones

Catechins

Catechins (fig. 4.) generally contain the parent structure of flavonoids and are mainly found in medicinal plants like grapes, apples, legumes, buckwheat, tea, etc. [57-59] and generally classified into different types, such as epicatechin, epicatechin gallate, (2)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, etc. Du et al. 2019 observed that at the dose of 20 mg/kg, epigallocatechin exhibited better efficacy in the DSS-induced colitis model [60]. It also helps to mitigate the DSS-induced colitis (at the dose of 50 mg/kg) in the experimental rat model by showing potent inhibition of inflammatory markers [61, 62].

Fig. 4: Chemical structures of isoflavones

Through this discussion, it became evident that flavonoids can be further utilized for the development of novel therapies against IBD. However, flavonoid-based drug development often faces challenges related to low bioavailability, poor absorption, and other issues. To overcome these challenges, researchers suggested several techniques so that more efficient therapies can be developed. Absorption efficiency is influenced by glycosylation; for instance, quercetin in its glycosylated form is more readily absorbed, whereas catechin, a non-glycosylated flavonoid, is absorbed with comparable efficiency. For example, the reduced absorption of certain flavonoids, leading to higher colonic concentrations, suggests their potential role in mitigating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathogenesis [63]. To increase the bioavailability of flavonoids in vivo, scientists focus on improving some metabolic processes related to bioavailability, such as boosting intestinal absorption, improving metabolic stability, moving absorption site, and so on. Nano-delivery techniques have been used to achieve the aforementioned goals with flavonoids. Recently, with the discovery of biodegradable polymers, flavonoid-loaded polymeric NPs have become an increasingly popular therapeutic approach for IBD, as they can increase stability and absorption while also changing the absorption site [64]. While flavonoids have health advantages, many data have also confirmed that flavonoids have exhibited significant liver-protection and renal-protection properties in vitro and in vivo [65]. Few studies have even highlighted the toxicity issues related to the usage of flavonoids. One such study stated that large doses of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) may cause hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. The specific causes are unknown, although it is suggested that high ingestion may cause oxidative stress, which contributes to liver and kidney damage. Similarly, quercetin has been associated with kidney damage. Flavonoids may also have an effect on thyroid function, with the effects varying depending on the duration of consumption and exposure. Although multiple in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that flavonoids can interfere with thyroid metabolism, the underlying mechanisms are complex and warrant additional exploration. Notably, quercetin has been reported to have thyroid-disrupting effects [66].

CONCLUSION

Inflammatory bowel disease is one of the most prevalent diseases spreading all over the world, and novel therapies need to be developed to treat it. Natural products, specifically plant-based, play an important role in the same and can be utilized for developing safer and more efficacious treatments against IBD. In our current review work, the role of plant-based flavonoids in the treatment of IBD was explained by demonstrating the published scientific works that showed this class of phytocompound showed moderate to good results in different in vitro and in vivo models. Our work also described that inflammation exerts a key role in the progression of IBD, and the same can be inhibited by decreasing or downregulating different inflammatory markers like IL-1b, IL-6, TNF-α, etc. Also, information related to some experimental animal models was discussed which may help the researchers to do future work in this direction. However, further clinical studies need to be done in order to get more information regarding the safety, clinical efficacy, and dosage of the natural flavonoid compounds so it helps for further drug development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors like to acknowledge Bapuji Pharmacy College, Davangere and Department of pharmacy, Banasthali University, Rajasthan for their continuous support by providing necessary information related to this work.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Samriti Faujdar: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review andamp; editing

Prabha Hullatti: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Nabarun Mukhopadhyay: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft.

A P Basavarajappa: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft.

Saraswati Patel: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Park SC, Jeen YT. Genetic studies of inflammatory bowel disease focusing on Asian patients. Cells. 2019 May 1;8(5):404. doi: 10.3390/cells8050404, PMID 31052430.

Martin DA, Bolling BW. A review of the efficacy of dietary polyphenols in experimental models of inflammatory bowel diseases. Food Funct. 2015 May 13;6(6):1773-86. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00202h, PMID 25986932.

Duan L, Cheng S, LI L, Liu Y, Wang D, Liu G. Natural anti-inflammatory compounds as drug candidates for inflammatory bowel disease. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jul 14;12:684486. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.684486, PMID 34335253.

Fakhoury M, Negrulj R, Mooranian A, Al Salami H. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and treatments. J Inflamm Res. 2014 Jun 23;7:113-20. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S65979, PMID 25075198.

Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Nov 1;169(11):1053-60. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1982, PMID 26414706.

Lee D, Albenberg L, Compher C, Baldassano R, Piccoli D, Lewis JD. Diet in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jan 15;148(6):1087-106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.007, PMID 25597840.

Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, Hamilton B, Bewshea C, Walker GJ. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal crohns disease: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Feb 27;4(5):341-53. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30012-3, PMID 30824404.

Bhakta A, Tafen M, Glotzer O, Ata A, Chismark AD, Valerian BT. Increased incidence of surgical site infection in IBD patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016 Apr;59(4):316-22. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000550, PMID 26953990.

Hounsome N, Hounsome B, Tomos D, Edwards Jones GE. Plant metabolites and nutritional quality of vegetables. J Food Sci. 2008 Apr 2;73(4):R48-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00716.x, PMID 18460139.

Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Remesy C, Jimenez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 May 1;79(5):727-47. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727, PMID 15113710.

Han X, Shen T, Lou H. Dietary polyphenols and their biological significance. Int J Mol Sci. 2007 Sep 12;8(9):950-88. doi: 10.3390/i8090950.

Huang WY, Cai YZ, Zhang Y. Natural phenolic compounds from medicinal herbs and dietary plants: potential use for cancer prevention. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62(1):1-20. doi: 10.1080/01635580903191585, PMID 20043255.

Wirtz S, Neurath MF. Mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007 Sep 30;59(11):1073-83. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.07.003, PMID 17825455.

Gao X, Feng X, Hou T, Huang W, MA Z, Zhang D. The roles of flavonoids in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and extra intestinal manifestations: a review. Food Biosci. 2024 Nov 8;62:105431. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105431.

Deshmukh CD. A review on inflammatory bowel disease. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023 Jun 7;16(6):11-4. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i6.47124.

Tao F, Qian C, Guo W, Luo Q, XU Q, Sun Y. Inhibition of Th1/Th17 responses via suppression of STAT1 and STAT3 activation contributes to the amelioration of murine experimental colitis by a natural flavonoid glucoside icariin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(6):798-807. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.12.002, PMID 23261528.

Caddeo C, Nacher A, Diez Sales O, Merino Sanjuan M, Fadda AM, Manconi M. Chitosan xanthan gum microparticle based oral tablet for colon targeted and sustained delivery of quercetin. J Microencapsul. 2014 Jun 6;31(7):694-9. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2014.913726, PMID 24903450.

JU S, GE Y, LI P, Tian X, Wang H, Zheng X. Dietary quercetin ameliorates experimental colitis in mouse by remodeling the function of colonic macrophages via a heme oxygenase-1-dependent pathway. Cell Cycle. 2018 Jan 2;17(1):53-63. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1387701, PMID 28976231.

Dodda D, Chhajed R, Mishra J, Padhy M. Targeting oxidative stress attenuates trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid induced inflammatory bowel disease like symptoms in rats: role of quercetin. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014 Jun;46(3):286-91. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.132160, PMID 24987175.

Dodda D, Chhajed R, Mishra J. Protective effect of quercetinagainst acetic acid induced inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) like symptoms in rats: possible morphological and biochemical alterations. Pharmacol Rep. 2014 Feb 19;66(1):169-73. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2013.08.013.

Diez Echave P, Ruiz Malagon AJ, Molina Tijeras JA, Hidalgo Garcia L, Vezza T, Cenis Cifuentes L. Silk fibroin nanoparticles enhance quercetin immunomodulatory properties in DSS-induced mouse colitis. Int J Pharm. 2021;606:120935. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120935, PMID 34310954.

Dong Y, Lei J, Zhang B. Dietary quercetin alleviated DSS-induced colitis in mice through several possible pathways by transcriptome analysis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2020;21(15):1666-73. doi: 10.2174/1389201021666200711152726, PMID 32651963.

Yan B, LI X, Zhou L, Qiao Y, WU J, Zha L. Inhibition of IRAK 1/4 alleviates colitis by inhibiting TLR4/ NF-κB pathway and protecting the intestinal barrier. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2022 Oct 23;22(6):872-81. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2022.7348, PMID 35699749.

Semwal DK, Semwal RB, Combrinck S, Viljoen A. Myricetin: a dietary molecule with diverse biological activities. Nutrients. 2016 Feb 16;8(2):90. doi: 10.3390/nu8020090, PMID 26891321.

Jones JR, Lebar MD, Jinwal UK, Abisambra JF, Koren J, Blair L. The diarylheptanoid (+)-aR,11S-myricanol and two flavones from bayberry (Myrica cerifera) destabilize the microtubule associated protein tau. J Nat Prod. 2011 Jan 28;74(1):38-44. doi: 10.1021/np100572z, PMID 21141876.

Wang L, WU H, Yang F, Dong W. The protective effects of myricetin against cardiovascular disease. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2019;65(6):470-6. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.65.470, PMID 31902859.

QU X, LI Q, Song Y, Xue A, Liu Y, QI D. Potential of myricetin to restore the immune balance in dextran sulfate sodium induced acute murine ulcerative colitis. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2020 Jan 1;72(1):92-100. doi: 10.1111/jphp.13197, PMID 31724745.

CI X, Chu X, Wei M, Yang X, Cai Q, Deng X. Different effects of farrerol on an OVA-induced allergic asthma and LPS-induced acute lung injury. Plos One. 2012;7(4):e34634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034634, PMID 22563373.

Nabavi SF, Khan H, D Onofrio G, Samec D, Shirooie S, Dehpour AR. Apigenin as neuroprotective agent: of mice and men. Pharmacol Res. 2018 Feb;128:359-65. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.10.008, PMID 29055745.

YU T, Xiong Y, Luu S, You X, LI B, Xia J. The shared KEGG pathways between icariin targeted genes and osteoporosis. Aging. 2020 May 7;12(9):8191-201. doi: 10.18632/aging.103133, PMID 32380477.

Marquez Flores YK, Villegas I, Cardeno A, Rosillo MA, Alarcon-de-la-Lastra C. Apigenin supplementation protects the development of dextran sulfate sodium induced murine experimental colitis by inhibiting canonical and non canonical inflammasome signaling pathways. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;30:143-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.12.002, PMID 27012631.

Aziz N, Kim MY, Cho JY. Anti-inflammatory effects of luteolin: a review of in vitro-in vivo and in silico studies. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018 Oct 28;225:342-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.019, PMID 29801717.

Imran M, Salehi B, Sharifi Rad J, Aslam Gondal T, Saeed F, Imran A. Kaempferol: a key emphasis to its anticancer potential. Molecules. 2019 Jun 19;24(12):2277. doi: 10.3390/molecules24122277, PMID 31248102.

Karrasch T, Kim JS, Jang BI, Jobin C. The flavonoid luteolin worsens chemical induced colitis in NF-κBEGFP transgenic mice through blockade of NF-κB-dependent protective molecules. Plos One. 2007 Jul 4;2(7):e596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000596.

Nunes C, Almeida L, Barbosa RM, Laranjinha J. Luteolin suppresses the JAK/STAT pathway in a cellular model of intestinal inflammation. Food Funct. 2017;8(1):387-96. doi: 10.1039/c6fo01529h, PMID 28067377.

Zaidun NH, Thent ZC, Latiff AA. Combating oxidative stress disorders with citrus flavonoid: naringenin. Life Sci. 2018 Sep 1;208:111-22. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.07.017, PMID 30021118.

Zeng W, Jin L, Zhang F, Zhang C, Liang W. Naringenin as a potential immunomodulator in therapeutics. Pharmacol Res. 2018 Sep;135:122-6. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.002, PMID 30081177.

Pinho Ribeiro FA, Zarpelon AC, Fattori V, Manchope MF, Mizokami SS, Casagrande R. Naringenin reduces inflammatory pain in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2016 Jun;105:508-19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.02.019, PMID 26907804.

Dou W, Zhang J, Sun A, Zhang E, Ding L, Mukherjee S. Protective effect of naringenin against experimental colitis via suppression of toll-like receptor 4/NF-κB signalling. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(4):599-608. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512005594, PMID 23506745.

Al Rejaie SS, Abuohashish HM, Al Enazi MM, Al Assaf AH, Parmar MY, Ahmed MM. Protective effect of naringenin on acetic acid induced ulcerative colitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep 14;19(34):5633-44. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5633, PMID 24039355.

Ran X, LI Y, Chen G, FU S, HE D, Huang B. Farrerol ameliorates TNBS-induced colonic inflammation by inhibiting ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):2037. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072037, PMID 30011811.

Azuma T, Shigeshiro M, Kodama M, Tanabe S, Suzuki T. Supplemental naringenin prevents intestinal barrier defects and inflammation in colitic mice. J Nutr. 2013 Jun;143(6):827-34. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.174508, PMID 23596159.

Liu D, WU J, Xie H, Liu M, Takau I, Zhang H, Xiong Y, Xia C. Inhibitory effect of hesperetin and naringenin on Human UDP-glucuronosyl transferase enzymes: implications for herb drug interactions. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016;39(12):2052-9. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00581.

Gonzalez Alfonso JL, Miguez N, Padilla JD, Leemans L, Poveda A, Jimnez Barbero J. Optimization of regioselective α-glucosylation of hesperetin catalyzed by cyclodextrin glucanotransferase. Molecules. 2018 Nov 5;23(11):2885. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112885, PMID 30400664.

Shirzad M, Heidarian E, Beshkar P, Gholami Arjenaki M. Biological effects of hesperetin on interleukin-6/phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway signaling in prostate cancer PC3 cells. Pharmacogn Res. 2017;9(2):188-94. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.204655, PMID 28539744.

Elhennawy MG, Abdelaleem EA, Zaki AA, Mohamed WR. Cinnamaldehyde and hesperetin attenuate TNBS induced ulcerative colitis in rats through modulation of the JAk2/STAT3/SOCS3 pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021 May;35(5):e22730. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22730, PMID 33522063.

Zhang J, Lei H, HU X, Dong W. Hesperetin ameliorates DSS-induced colitis by maintaining the epithelial barrier via blocking RIPK3/MLKL necroptosis signaling. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020 Apr 15;873:172992. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.172992, PMID 32035144.

Polat FR, Karaboga I, Polat MS, Erboga Z, Yilmaz A, Guzel S. Effect of hesperetin on inflammatory and oxidative status in trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid induced experimental colitis model. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2018 Aug 30;64(11):58-65. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2018.64.11.11, PMID 30213290.

Jaakola L. New insights into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18(9):477-83. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.06.003, PMID 23870661.

Sui X, Zhang Y, Zhou W. Bread fortified with anthocyanin richextract from black rice as nutraceutical sources: its quality attributes and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2016 Apr 1;196:910-6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.113.

Silva S, Costa EM, Calhau C, Morais RM, Pintado ME. Anthocyanin extraction from plant tissues: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017 Sep 22;57(14):3072-83. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1087963, PMID 26529399.

WU LH, XU ZL, Dong D, HE SA, YU H. Protective effect of anthocyanins extract from blueberry on TNBS induced IBD model of mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011 Apr 14;2011:525462. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq040, PMID 21785630.

Piberger H, Oehme A, Hofmann C, Dreiseitel A, Sand PG, Obermeier F. Bilberries and their anthocyanins ameliorate experimental colitis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011 Nov;55(11):1724-9. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100380, PMID 21957076.

Zhao L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Hao S, Wang C, Wang Y. Black rice anthocyanin rich extract and rosmarinic acid alone and in combination protect against DSS induced colitis in mice. Food Funct. 2018 Apr 18;9(5):2796-808. doi: 10.1039/c7fo01490b, PMID 29691532.

Zhang J, Lei H, HU X, Dong W. Hesperetin ameliorates DSS induced colitis by maintaining the epithelial barrier via blocking RIPK3/MLKL necroptosis signaling. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020 Apr 15;873:172992. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.172992, PMID 32035144.

Abron JD, Singh NP, Price RL, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS, Singh UP. Genistein induces macrophage polarization and systemic cytokine to ameliorate experimental colitis. Plos One. 2018 Jul 18;13(7):e0199631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199631, PMID 30024891.

Fathima A, Rao JR. Selective toxicity of catechin a natural flavonoid towards bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016 Apr 6;100(14):6395-402. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7492-x, PMID 27052380.

Martinez Leal J, Valenzuela Suarez L, Jayabalan R, Huerta Oros J, Escalante-Aburto A. A review on health benefits of kombucha nutritional compounds and metabolites. CyTA J Food. 2018 Feb 12;16(1):390-9. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2017.1410499.

Cardoso RR, Neto RO, Dos Santos D, Almeida CT, DO Nascimento TP, Pressete CG, Azevedo L. Kombuchas from green and black teas have different phenolic profile which impacts their antioxidant capacities antibacterial and antiproliferative activities. Food Res Int. 2020 Feb;128:108782. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108782, PMID 31955755.

DU Y, Ding H, Vanarsa K, Soomro S, Baig S, Hicks J. Low dose epigallocatechin gallate alleviates experimental colitis by subduing inflammatory cells and cytokines and improving intestinal permeability. Nutrients. 2019 Jul 29;11(8):1743. doi: 10.3390/nu11081743, PMID 31362373.

Mascia C, Maina M, Chiarpotto E, Leonarduzzi G, Poli G, Biasi F. Proinflammatory effect of cholesterol and its oxidation products on CaCo-2 human enterocyte like cells: effective protection by epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010 Dec;49(12):2049-57. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.033, PMID 20923702.

Sergent T, Piront N, Meurice J, Toussaint O, Schneider YJ. Anti-inflammatory effects of dietary phenolic compounds in an in vitro model of inflamed human intestinal epithelium. Chem Biol Interact 2010;188(3):659-67. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.08.007, PMID 20816778.

Louis Jean S. Clinical outcomes of flavonoids for immunomodulation in inflammatory bowel disease: a narrative review. Ann Gastroenterol. 2024 Jun 14;37(4):392-402. doi: 10.20524/aog.2024.0893, PMID 38974082.

LI M, Liu Y, Weigmann B. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles loaded with flavonoids: a promising therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 23;24(5):4454. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054454, PMID 36901885.

Kandemir FM, Yıldırım S, Kucukler S, Caglayan C, Darendelioglu E, Dortbudak MB. Protective effects of morin against acrylamide induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity: a multi biomarker approach. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020 Apr;138:111190. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111190, PMID 32068001.

Tang Z, Zhang Q. The potential toxic side effects of flavonoids. Biocell. 2022 Oct 20;46(2):357-66. doi: 10.32604/biocell.2022.015958.