Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 8, 53-63Original Article

MOLECULAR DOCKING AND IN SILICO STUDIES ON RIBULOSE-1,5-BISPHOSPHATE CARBOXYLASE PROTEIN FROM TECTICORNIA INDICA POSSESSING ANTICANCER PROPERTY, INHIBITORY FUNCTION AGAINST DHFR AND EGFR

SARANG TANVI, GUPTA PRAMODKUMAR P, MHATRE BHAKTI*

School of Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, D. Y. Patil Deemed to be University, Sector 15, CBD Belapur, Navi Mumbai-400614, Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding author: Mhatre Bhakti; *Email: bhaktiamhatre@gmail.com

Received: 03 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 11 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Tecticornia indica is a halophytic plant known for its remarkable tolerance to salinity, flooding, tidal conditions, and drought. Tecticornia indica (Willd.) subsp. indica, also referred to as Artrocnemum indica (Willd.) and Halosarcia indica (Willd.), is rich in vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds with notable antibacterial properties. In coastal regions, it is commonly consumed as a local vegetable. In this study, we employed DNA barcoding to accurately identify Tecticornia indica and explored its bioactive potential using in silico methods.

Methods: Barcoding was used to confirm the identity of Tecticornia indica. The Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO) protein sequence derived from this species was used to construct a three-dimensional model using Swiss-Model server. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using GROMACS (Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations) to analyze biomolecular interactions. Protein-protein docking was conducted with ClusPro server. We docked the RuBisCO protein with two cancer-related targets: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR). As controls, we also docked Tamoxifen, an established anticancer agent, with both EGFR and DHFR.

Results: Docking results revealed that the RuBisCO protein from Tecticornia indica exhibited favorable binding interactions with both EGFR and DHFR. Compared to Tamoxifen, RuBisCO demonstrated stronger binding affinities and more stable interactions, suggesting enhanced inhibitory potential.

Conclusion: Our docking studies indicate that the RuBisCO protein from Tecticornia indica may possess superior inhibitory properties against EGFR and DHFR compared to Tamoxifen. These findings suggest that Tecticornia indica holds promise as a natural source of bioactive compounds for anticancer drug development.

Keywords: Tecticornia indica, Bar coding, Epidermal growth factor receptor, Dihydrofolate reductase, Docking

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i8.54433 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

The chenopod Tecticornia indica (Willd.) subsp. indica, also known as Salicornia or Moq. is a member of the C4 photosynthetic group. It was later classified by Paul G. Wilson as Halosarcia indica (Willd.). This species exhibits anatomical characteristics typical of NAD-malic enzyme-type C4 plants, including mesophyll chloroplasts with reduced grana [1].

In dry or semi-arid regions, members of the Salicornioideae subfamily (Amaranthaceae) are considered underutilized plants, with Tecticornia spp. being notable representatives. The Amaranthaceae family includes several well-known and economically important food crops such as spinach, beets, chard, and quinoa. Interestingly, the Salicornioideae subfamily comprises approximately 110 species distributed across 11 genera, including Sarcocornia and Salicornia, which exhibit a wide range of climatic adaptations. Specifically, Tecticornia spp., like other halophytes, display exceptional salt tolerance and are well adapted to flood-prone, tidal, saline, and arid environments.

Fig. 1: Tecticornia indica plant

Tecticornia indica is a halophytic plant known to contain a range of natural compounds with demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, anti-atherosclerotic, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antimutagenic, and antiallergic properties [2]. It is also a rich source of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other bioactive compounds [3]. In recent years, marine-derived plants and algae have been increasingly explored to address food and feed shortages, especially in developing countries. These unconventional sources have emerged as promising long-term alternatives to traditional nutritional resources [4].

Researchers have recognized such non-conventional (wild) food crops as potentially rich sources of nutrients, comparable to or exceeding those found in traditionally cultivated crops [5]. Many of these species are valued for their therapeutic properties and high nutritional content, including essential minerals, proteins, fibers, and fatty acids [6]. The seeds and young leaves of T. indica are traditionally used as seasonings in a variety of dishes.

Despite their potential, wild edible plants remain underexplored. Information on their medicinal and nutritional value is scarce, and their use has historically been limited by ecological and cultural perceptions. Submerged plants, such as T. indica, are often mischaracterized as nuisances due to their challenging habitats [7]. These plants can significantly alter the physicochemical properties of aquatic environments, affecting both water quality and hydrosoil composition [8]. Furthermore, they may provide habitats for larvae of disease vectors, such as those that transmit malaria, thereby posing potential public health risks [9].

Nevertheless, the antioxidant capacity of such halophytic species may confer substantial therapeutic benefits, including anticancer potential [10]. Cancer remains a major global health challenge, affecting both developing and developed nations [11]. Current synthetic chemotherapeutic agents often fall short due to high development costs and limited accessibility. This underscores the need for alternative, cost-effective cancer treatments, particularly for low-income populations.

This study aims to evaluate the anticancer potential of biomolecules derived from Tecticornia indica using molecular docking techniques. We used DNA barcoding to obtain the sequence of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO) protein and constructed a three-dimensional model using the Swiss-Model server platform. Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using GROMACS to explore biomolecular interactions.

The RuBisCO protein model from T. indica was docked with two cancer-related protein targets: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR). EGFR plays a pivotal role in cellular differentiation and proliferation [13]. As a control, we also docked Tamoxifen, a widely used anticancer drug, with both EGFR and DHFR.

Docking studies revealed that the RuBisCO protein from T. indica demonstrated superior binding affinity and inhibitory properties compared to Tamoxifen when interacting with both EGFR and DHFR. These findings highlight the potential of T. indica as a source of novel anticancer compounds and support its further investigation in the development of low-cost, plant-based therapeutic agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After collection, the leaves and young twigs were removed, thoroughly washed with water, and oven-dried at 105 °C for 5–7 h. The dried plant material was ground into a fine powder, stored in a cool and dry place, and then submitted for DNA barcoding. The nucleotide sequence obtained for Tecticornia indica was accepted by GenBank and assigned the accession number bankit2721068: tecticornia_indica_btmp_cultivar1_OR246886.

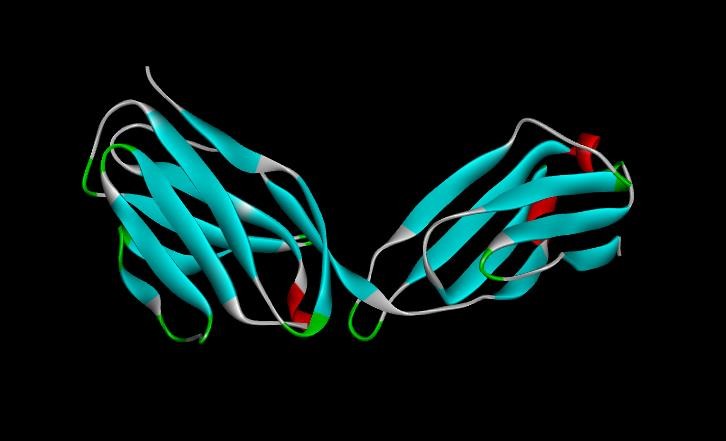

Protein structure modeling and molecular docking

The ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein sequence of Halosarcia (Accession No.: AAQ75644.1) was selected due to its sequence similarity to Tecticornia indica. This sequence was retrieved from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and used for homology modeling via the SWISS-MODEL server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/). The amino acid sequence was uploaded to the Swiss-Model server homepage, and a suitable template was selected based on sequence similarity. The 3D protein structure was generated through the automated modeling process and subsequently downloaded in PDB format.

To optimize the modeled structure, we employed GROMACS (GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations) for Molecular Dynamics Simulation (MDS). A 10-nanosecond simulation was performed to refine the structure of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase enzyme.

Protein-protein and ligand docking

-

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (PDB DOI: 10.2210/pdb1BOZ/pdb)

-

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) (PDB DOI: 10.2210/pdb3P0V/pdb)

As a control, the anticancer drug Tamoxifen was also docked (PDB DOI: 10.2210/pdb2EWP/pdb).

All 3D structures used in this study were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/). Prior to docking, ligands and water molecules were removed from each structure using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer, and the cleaned structures were saved in PDB format.

Docking was performed using the ClusPro server. Users are required to register, upload receptor and ligand files in PDB format, and initiate docking by selecting the “Dock” option. The results, including docked conformations, were typically received within 24 h to 8 d, depending on the queue and server load.

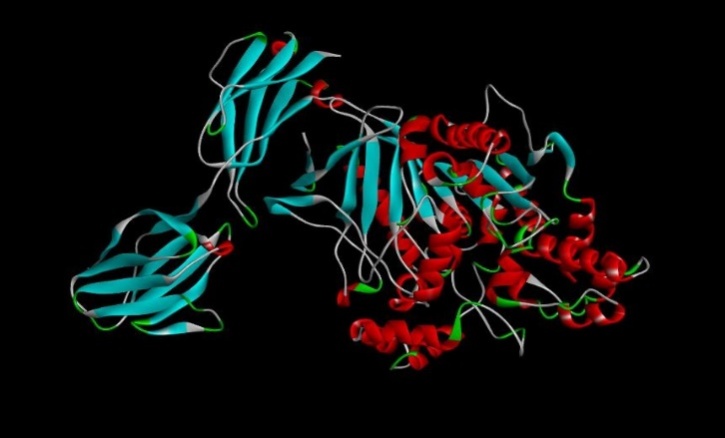

Fig. 2: 3D Structure of Ribulos-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase

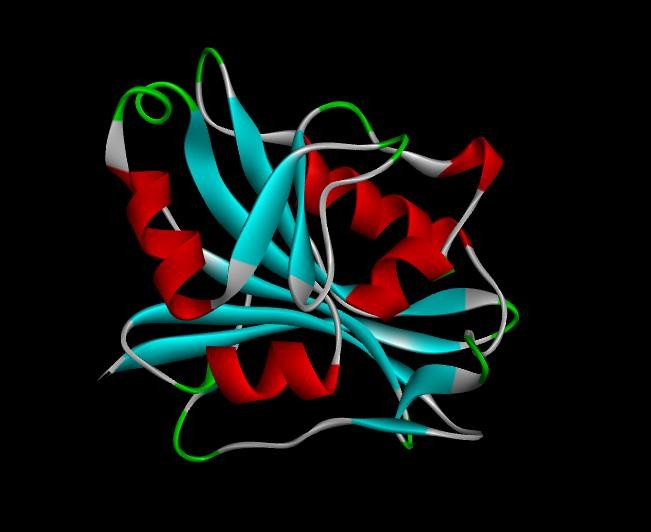

Fig. 3: 3D structure of EGF

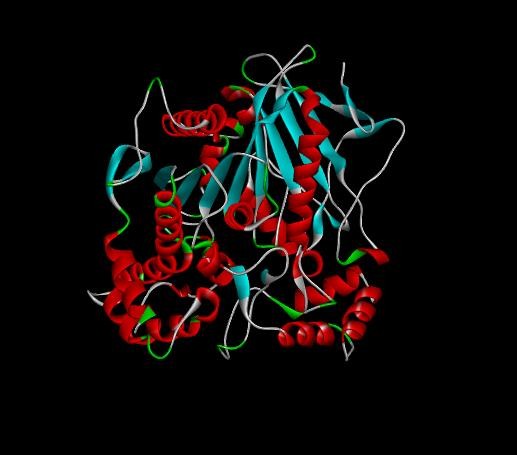

Fig. 4: 3D Structure of DHFR

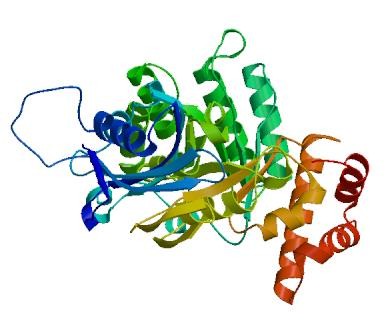

Fig. 5: 3D Structure of tamoxifen drug

RESULTS

Docking on Tecticornia indica (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein)

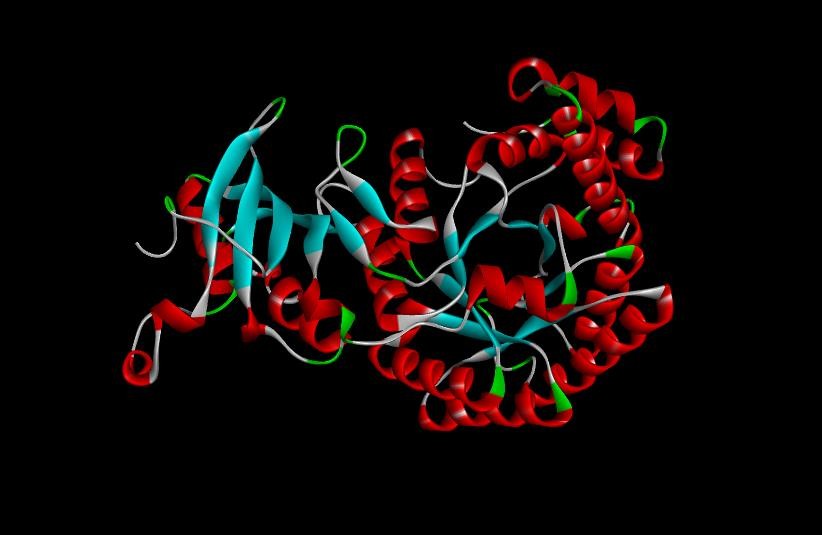

Constructed ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase 3D structure

We used the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein sequence from Tecticornia indica (GenBank Accession No.: AAQ75644.1) to construct a three-dimensional protein model. The structure was generated using Swiss-Model server, an automated web-based homology modeling platform (fig. 6).

Swiss-Model server is a widely used tool for predicting the three-dimensional structures of proteins based on their amino acid sequences. It employs comparative (homology-based) modeling techniques, aligning target sequences with experimentally determined protein structures. The platform utilizes a comprehensive library of known protein structures to generate high-quality structural models for proteins whose structures have not yet been resolved experimentally.

Optimization of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase's 3D structure by GROMACS

We utilized GROMACS (GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations), a widely used molecular dynamics simulation software, to study the movement and interactions of biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. Although GROMACS is primarily recognized for its simulation capabilities, it also provides robust tools for protein structure optimization, including energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations (MDS).

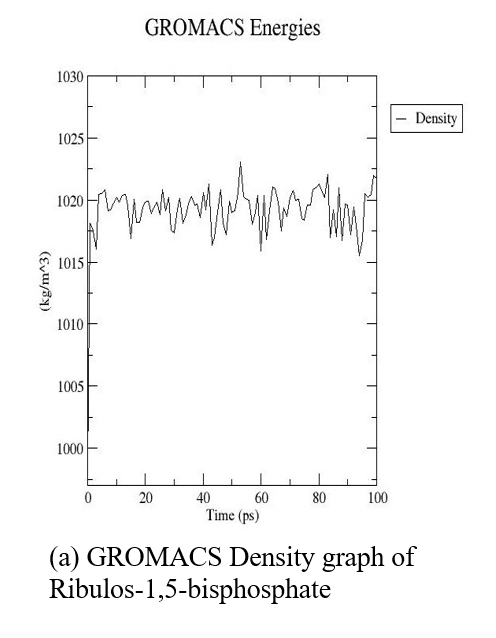

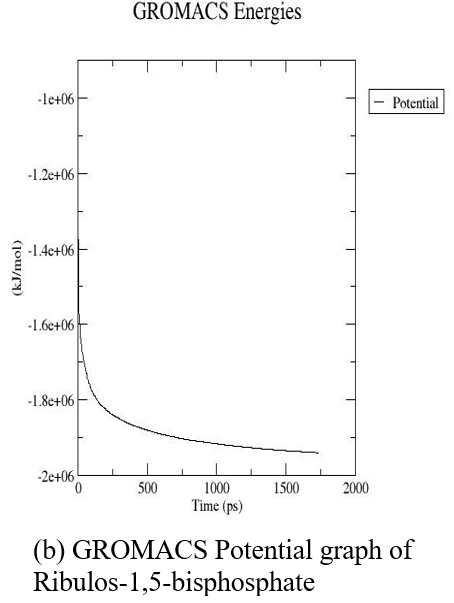

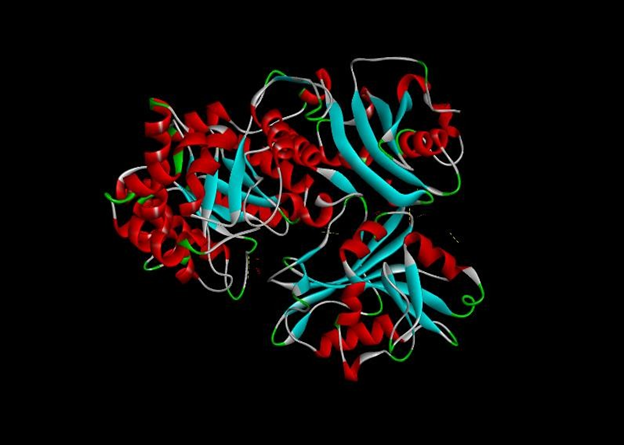

The three-dimensional structure of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase was subjected to MDS for 10 nanoseconds on a high-performance computing system (supercomputer). Following the simulation, we obtained key output parameters such as density, pressure, and potential energy, along with the final optimized 3D protein structure (fig. 7 and 8).

Fig. 6: Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase 3D structure constructed by SWISS-MODEL

Fig. 7: GROMACS graphs (Density, pressure, potential) of ribulos-1.5-bisphosphate carboxylase

Fig. 8: A 3D structure of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase after GROMACS and molecular dynamics simulation (MDS)

Protein-protein docking to check anticancer effects

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) play a central role in numerous biological processes, including signal transduction, enzyme regulation, and immune responses [14]. Understanding the structural basis of these interactions is essential for elucidating functional mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

To investigate these interactions, we employed ClusPro server a widely used and validated tool for protein–protein docking. In this study, the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein and the anticancer drug Tamoxifen (used as a control) were docked separately with two cancer-related targets:

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (PDB DOI: 10.2210/pdb1BOZ/pdb)

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) (PDB DOI: 10.2210/pdb3P0V/pdb)

These docking experiments were designed to evaluate the interaction profiles and inhibitory potential of the plant-derived protein in comparison with the established anticancer drug.

Docking of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase with DHFR

Protein–protein docking was performed between ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) to evaluate their molecular interactions and investigate the potential anticancer activity of the plant-derived protein. The docking procedure was conducted using the ClusPro server (https://cluspro.bu.edu/login.php).

Among the generated docking models, the one exhibiting the lowest binding energy was selected for analysis, as it represents the most energetically favorable interaction between the two molecules. This suggests that the docking substrate (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase) may facilitate a stable and spontaneous interaction with DHFR.

Table 1 presents the top ten docking poses with the lowest binding energies between DHFR and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase, indicating favorable binding conformations. Fig. 9 illustrates the binding interface of the best-docked complex.

The purpose of this docking study was to assess whether ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase can bind effectively to DHFR in a low-energy, biologically relevant conformation. The observed negative binding energies support the hypothesis that this plant-derived protein could act as a potential DHFR inhibitor, making it a promising candidate for anticancer research.

Docking of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase with EGFR

To investigate the interaction between ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)-a key regulator of cell proliferation and survival-protein–protein docking was carried out using the ClusPro server (https://cluspro.bu.edu/login.php). This study aimed to evaluate the anticancer potential of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase through its interaction with EGFR.

Among the docking models generated, the one with the lowest binding energy was selected for further analysis, indicating the most energetically favorable interaction. This suggests that the protein substrate may facilitate a spontaneous and stable interaction with EGFR (fig. 10). The top ten binding conformations based on energy scores are presented in table 3, highlighting the predicted binding affinity between ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and EGFR.

The docking analysis demonstrated negative binding energies, which typically indicate spontaneous binding and favorable interaction in thermodynamic terms. Based on these results, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase shows potential as a candidate EGFR inhibitor, supporting its role in anticancer activity.

Table 1: Binding energies of top 10 models of Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase with DHFR

| S. No. | Members | Binding energy |

| 0 | 169 | -1019.9 |

| 1 | 141 | -782.7 |

| 2 | 111 | -745.3 |

| 3 | 108 | -1097.2 |

| 4 | 78 | -772.1 |

| 5 | 55 | -692.8 |

| 6 | 30 | -733.7 |

| 7 | 29 | -797.0 |

| 8 | 28 | -882.6 |

| 9 | 28 | -742.1 |

| 10 | 28 | -736.4 |

Fig. 9: Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein docked with DHFR

Table 2: Interaction table of Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase with DHFR (Intermolecular within the molecules)

| Name | Visible | Color | Parent | Distance | Category | Type | From | From chemistry | To | To Chemistry | Angle DHA | Angle HAY | Angle XDA | Angle DAY |

| A: LYS107:HZ3-A: GLU101:OE2 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.88242 | Hydrogen Bond; Electrostatic | Salt bridge; Attractive Charge | A: LYS107:HZ3 | H-Donor; Positive | A: GLU101:OE2 | H-Acceptor; Negative | 130.101 | 127.875 | ||

| A: LYS156:NZ-A: GLU143:OE2 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.35709 | Electrostatic | Attractive charge | A: LYS156:NZ | Positive | A: GLU143:OE2 | Negative | ||||

| A: GLN24:HE21-A: ASP94:OD2 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.96981 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional hydrogen bond | A: GLN24:HE21 | H-Donor | A: ASP94:OD2 | H-Acceptor | 140.768 | 106.624 | ||

| A: GLY105:H-A: ASN126:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.60629 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional hydrogen bond | A: GLY105:H | H-Donor | A: ASN126:O | H-Acceptor | 112.467 | 111.611 | ||

| A: HIS127:CD2-A: GLY105:O | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.98709 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-hydrogen bond | A: HIS127:CD2 | H-Donor | A: GLY105:O | H-Acceptor | 104.983 | 139.561 | ||

| A: PRO128:CD-A: GLY105:O | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.63776 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-hydrogen bond | A: PRO128:CD | H-Donor | A: GLY105:O | H-Acceptor | 122.413 | 95.403 | ||

| A: VAL279-A: PRO149 | Yes | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.28166 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: VAL279 | Alkyl | A: PRO149 | Alkyl | ||||

| A: PHE106-A: PRO128 | Yes | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.47704 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | A: PHE106 | Pi-Orbitals | A: PRO128 | Alkyl |

Table 3: Binding energies of top 10 models of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase with EGFR

| S. No. | Members | Binding energy |

| 0 | 85 | -892.4 |

| 1 | 79 | -793.6 |

| 2 | 42 | -800.0 |

| 3 | 42 | -833.7 |

| 4 | 36 | -774.3 |

| 5 | 32 | -750.4 |

| 6 | 32 | -746.1 |

| 7 | 31 | -718.8 |

| 8 | 31 | -795.1 |

| 9 | 30 | -799.4 |

| 10 | 24 | -841.1 |

Table 4: Interaction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase with EGFR (Intermolecular within the molecules)

| Name | Visible | Color | Parent | Distance | Category | Type | From | From Chemistry | To | To Chemistry | Angle DHA | Angle HAY | Angle XDA | Angle DAY | Theta |

| L: LYS190:HZ1-A: GLU89:OE2 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.74233 | Hydrogen Bond; Electrostatic | Salt Bridge; Attractive Charge | L: LYS190:HZ1 | H-Donor; Positive | A: GLU89:OE2 | H-Acceptor; Negative | 138.938 | 103.809 | |||

| L: LYS190:HZ2-A: GLU89:OE1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.75536 | Hydrogen Bond; Electrostatic | Salt Bridge; Attractive Charge | L: LYS190:HZ2 | H-Donor; Positive | A: GLU89:OE1 | H-Acceptor; Negative | 132.488 | 108.129 | |||

| A: ARG58:HH21-L: ASP122:OD2 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.91866 | Hydrogen Bond; Electrostatic | Salt Bridge; Attractive Charge | A: ARG58:HH21 | H-Donor; Positive | L: ASP122:OD2 | H-Acceptor; Negative | 140.345 | 110.256 | |||

| A: ARG58:HH22-L: ASP122:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.17678 | Hydrogen Bond; Electrostatic | Salt Bridge; Attractive Charge | A: ARG58:HH22 | H-Donor; Positive | L: ASP122:OD1 | H-Acceptor; Negative | 119.529 | 112.616 | |||

| A: LYS107:HZ1-L: ASP170:OD2 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.83783 | Hydrogen Bond; Electrostatic | Salt Bridge; Attractive Charge | A: LYS107:HZ1 | H-Donor; Positive | L: ASP170:OD2 | H-Acceptor; Negative | 117.699 | 106.236 | |||

| A: ARG58:NH1-L: ASP122:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.06399 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG58:NH1 | Positive | L: ASP122:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| L: SER114:HG-A: GLU39:OE1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.97185 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: SER114:HG | H-Donor | A: GLU39:OE1 | H-Acceptor | 159.376 | 138.904 | |||

| L: SER121:H-A: LEU53:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.02086 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: SER121:H | H-Donor | A: LEU53:O | H-Acceptor | 146.097 | 160.803 | |||

| L: SER121:HG-A: LEU53:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.85264 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: SER121:HG | H-Donor | A: LEU53:O | H-Acceptor | 159.215 | 129.719 | |||

| L: ASN138:HD22-A: GLU39:OE1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.02334 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: ASN138:HD22 | H-Donor | A: GLU39:OE1 | H-Acceptor | 148.996 | 127.894 | |||

| L: LYS207:HZ1-A: SER40:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.73788 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: LYS207:HZ1 | H-Donor | A: SER40:O | H-Acceptor | 122.309 | 139.947 | |||

| L: LYS207:HZ1-A: SER41:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.33515 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: LYS207:HZ1 | H-Donor | A: SER41:O | H-Acceptor | 127.959 | 107.179 | |||

| L: LYS207:HZ2-A: THR97:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.704 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: LYS207:HZ2 | H-Donor | A: THR97:O | H-Acceptor | 167.244 | 141.033 | |||

| L: SER208:H-A: ASN94:OD1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.28696 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: SER208:H | H-Donor | A: ASN94:OD1 | H-Acceptor | 140.618 | 119.091 | |||

| L: SER208:HG-A: GLU88:OE2 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.86857 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: SER208:HG | H-Donor | A: GLU88:OE2 | H-Acceptor | 177.305 | 95.601 | |||

| L: ASN210:H-A: ASP85:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.53037 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: ASN210:H | H-Donor | A: ASP85:O | H-Acceptor | 155.672 | 166.472 | |||

| L: ASN210:H-A: PHE87:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.07463 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: ASN210:H | H-Donor | A: PHE87:O | H-Acceptor | 94.506 | 142.349 | |||

| L: ASN210:HD21-A: PHE87:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.98828 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | L: ASN210:HD21 | H-Donor | A: PHE87:O | H-Acceptor | 162.028 | 150.169 | |||

| A: TRP45:H-L: ASN137:OD1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.36267 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: TRP45:H | H-Donor | L: ASN137:OD1 | H-Acceptor | 170.42 | 90.963 | |||

| A: TRP45:HE1-L: SER174:OG | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.09006 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: TRP45:HE1 | H-Donor | L: SER174:OG | H-Acceptor | 132.245 | 96.373 | |||

| A: TRP49:HE1-L: SER176:OG | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.91113 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: TRP49:HE1 | H-Donor | L: SER176:OG | H-Acceptor | 148.565 | 112.789 | |||

| A: THR54:HG1-L: PRO119:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.78428 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: THR54:HG1 | H-Donor | L: PRO119:O | H-Acceptor | 166.387 | 150.131 | |||

| A: SER55:HG-L: ASP122:OD1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.36021 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: SER55:HG | H-Donor | L: ASP122:OD1 | H-Acceptor | 152.833 | 149.049 | |||

| A: ASN102:HD21-L: SER114:OG | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.9852 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ASN102:HD21 | H-Donor | L: SER114:OG | H-Acceptor | 166.587 | 121.603 | |||

| A: ASN102:HD22-L: ALA112:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.12729 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ASN102:HD22 | H-Donor | L: ALA112:O | H-Acceptor | 136.254 | 143.102 | |||

| L: LYS207:CE-A: SER98:OG | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.40284 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-Hydrogen Bond | L: LYS207:CE | H-Donor | A: SER98:OG | H-Acceptor | 98.669 | 111.366 | |||

| A: TRP45:CD1-L: ASN137:OD1 | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.92664 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-Hydrogen Bond | A: TRP45:CD1 | H-Donor | L: ASN137:OD1 | H-Acceptor | 119.949 | 129.392 | |||

| L: ASP167:OD1-A: TRP45 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.91885 | Electrostatic | Pi-Anion | L: ASP167:OD1 | Negative | A: TRP45 | Pi-Orbitals | 22.44 | ||||

| A: TYR59-L: PRO119 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.77592 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | A: TYR59 | Pi-Orbitals | L: PRO119 | Alkyl |

Table 5: Binding energies of top 10 models of tamoxifen drug with DHFR

| S. No. | Members | Binding energy |

| 0 | 85 | -504.3 |

| 1 | 68 | -503.4 |

| 2 | 53 | -567.6 |

| 3 | 46 | -522.2 |

| 4 | 44 | -526.9 |

| 5 | 42 | -486.9 |

| 6 | 33 | -670.6 |

| 7 | 32 | -539.5 |

| 8 | 29 | -520.7 |

| 9 | 29 | -498.4 |

| 10 | 27 | -533.0 |

Fig. 10: Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein docked with EGFR

Docking of tamoxifen with DHFR

To evaluate the interaction and anticancer potential of Tamoxifen, a well-known chemotherapeutic agent, protein–ligand docking was performed with Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) using the ClusPro server (https://cluspro.bu.edu/login.php).

Among the resulting docking models, the conformation with the lowest binding energy was selected, as it represents the most thermodynamically favorable interaction. This docking pose suggests that Tamoxifen may effectively bind to DHFR (fig. 11). The top ten binding energies between DHFR and Tamoxifen are summarized in table 5.

The goal of this docking study was to determine whether Tamoxifen could stably bind to DHFR in its most energetically favorable conformation. The observed negative binding energies indicate that Tamoxifen likely binds spontaneously, without requiring additional energy input. Based on these results, Tamoxifen can be considered a potent DHFR inhibitor, reinforcing its role in anticancer therapy.

Docking of Tamoxifen with EGFR

To evaluate the interaction between Tamoxifen and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), a protein–ligand docking study was performed using the ClusPro server (https://cluspro.bu.edu/login.php). This investigation aimed to assess the potential anticancer properties of Tamoxifen, particularly its ability to inhibit EGFR. It is well known that growth factors such as oncogenes, mutated tumor suppressor genes, and hormonal receptors (e. g., estrogen and progesterone) play crucial roles in cancer cell growth and proliferation through receptor-mediated signaling pathways.

The docking model with the lowest binding energy was selected for further analysis, as it represents the most energetically favorable interaction between Tamoxifen and EGFR (fig. 12). The top ten binding energies for this interaction are presented in table 7. In docking analysis, a negative binding energy typically indicates that the ligand (in this case, Tamoxifen) binds spontaneously and stably to the receptor. The observed negative binding energies in this study suggest that Tamoxifen interacts efficiently with EGFR, supporting its role as a potential EGFR inhibitor and affirming its effectiveness as an anticancer agent.

Fig. 11: Tamoxifen drug docked with DHFR

Fig. 13: Tamoxifen drug docked with EGFR

Table 6: Interaction of Tamoxifen drug with DHFR (Intermolecular within the molecules)

| Name | Visible | Color | Parent | Distance | Category | Type | From | From Chemistry | To | To Chemistry | Angle DHA | Angle HAY | Angle XDA | Angle DAY | Theta |

| A: ARG186:NH1-A: GLU143:OE1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.24201 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG186:NH1 | Positive | A: GLU143:OE1 | Negative | |||||

| A: ARG199:NH2-A: ASP21:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.44931 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG199:NH2 | Positive | A: ASP21:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| A: LYS18:NZ-A: ASP324:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.29829 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: LYS18:NZ | Positive | A: ASP324:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| A: ARG65:NH2-A: ASP203:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.90777 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG65:NH2 | Positive | A: ASP203:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| A: GLN69:HE21-A: ASP145:OD2 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.82404 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: GLN69:HE21 | H-Donor | A: ASP145:OD2 | H-Acceptor | 140.771 | 93.953 | |||

| A: ARG186:HH21-A: ASP141:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.9602 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG186:HH21 | H-Donor | A: ASP141: O | H-Acceptor | 120.289 | 110.658 | |||

| A: ARG199:HE-A: GLY20:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.62993 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HE | H-Donor | A: GLY20: O | H-Acceptor | 94.96 | 114.79 | |||

| A: ARG199:HH11-A: PHE58:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.51553 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HH11 | H-Donor | A: PHE58: O | H-Acceptor | 135.025 | 125.223 | |||

| A: ARG199:HH21-A: PHE58:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.46243 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HH21 | H-Donor | A: PHE58: O | H-Acceptor | 136.159 | 125.57 | |||

| A: ARG199:HH22-A: SER59:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.57678 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HH22 | H-Donor | A: SER59: O | H-Acceptor | 110.754 | 101.967 | |||

| A: GLN202:HE22-A: GLU62:OE1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.73138 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: GLN202:HE22 | H-Donor | A: GLU62:OE1 | H-Acceptor | 108.417 | 144.232 | |||

| A: ARG28:HH21-A: ASN340:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.77325 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG28:HH21 | H-Donor | A: ASN340: O | H-Acceptor | 101.182 | 111.394 | |||

| A: THR66:CA-A: GLU143:OE2 | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.04656 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | A: THR66:CA | H-Donor | A: GLU143:OE2 | H-Acceptor | 97.175 | 133.466 | |||

| A: ARG199:CD-A: ASN19:O | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.93401 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:CD | H-Donor | A: ASN19: O | H-Acceptor | 109.071 | 136.47 | |||

| A: PRO25:CD-A: GLY325:O | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.23162 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | A: PRO25:CD | H-Donor | A: GLY325: O | H-Acceptor | 101.133 | 159.832 | |||

| A: ARG186:NH2-A: PHE142 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.52237 | Electrostatic | Pi-Cation | A: ARG186:NH2 | Positive | A: PHE142 | Pi-Orbitals | 39.679 | ||||

| A: PRO67-A: LYS18 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.62908 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: PRO67 | Alkyl | A: LYS18 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: PRO234-A: PRO25 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.44989 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: PRO234 | Alkyl | A: PRO25 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: PRO25-A: LEU329 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.40277 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: PRO25 | Alkyl | A: LEU329 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: LYS173-A: LEU329 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.61158 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: LYS173 | Alkyl | A: LEU329 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: PHE142-A: MET326 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.29592 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | A: PHE142 | Pi-Orbitals | A: MET326 | Alkyl |

Table 7: Binding energies of top 10 models of Tamoxifen drug with EGFR

| S. No. | Members | Binding energy |

| 0 | 65 | -629.1 |

| 1 | 49 | -578.3 |

| 2 | 47 | -558.7 |

| 3 | 47 | -574.6 |

| 4 | 33 | -556.2 |

| 5 | 32 | -621.6 |

| 6 | 31 | -566.9 |

| 7 | 31 | -554.6 |

| 8 | 30 | -560.1 |

| 9 | 30 | -538.0 |

| 10 | 28 | -576.5 |

Table 8: Interaction of Tamoxifen drug with EGFR (Intermolecular within the molecules)

| Name | Visible | Color | Parent | Distance | Category | Type | From | From Chemistry | To | To chemistry | Angle DHA | Angle HAY | Angle XDA | Angle DAY | Theta |

| A: ARG186:NH1-A: GLU143:OE1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.24201 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG186:NH1 | Positive | A: GLU143:OE1 | Negative | |||||

| A: ARG199:NH2-A: ASP21:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.44931 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG199:NH2 | Positive | A: ASP21:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| A: LYS18:NZ-A: ASP324:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.29829 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: LYS18:NZ | Positive | A: ASP324:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| A: ARG65:NH2-A: ASP203:OD1 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.90777 | Electrostatic | Attractive Charge | A: ARG65:NH2 | Positive | A: ASP203:OD1 | Negative | |||||

| A: GLN69:HE21-A: ASP145:OD2 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.82404 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: GLN69:HE21 | H-Donor | A: ASP145:OD2 | H-Acceptor | 140.771 | 93.953 | |||

| A: ARG186:HH21-A: ASP141:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 1.9602 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG186:HH21 | H-Donor | A: ASP141:O | H-Acceptor | 120.289 | 110.658 | |||

| A: ARG199:HE-A: GLY20:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.62993 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HE | H-Donor | A: GLY20:O | H-Acceptor | 94.96 | 114.79 | |||

| A: ARG199:HH11-A: PHE58:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.51553 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HH11 | H-Donor | A: PHE58:O | H-Acceptor | 135.025 | 125.223 | |||

| A: ARG199:HH21-A: PHE58:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.46243 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HH21 | H-Donor | A: PHE58:O | H-Acceptor | 136.159 | 125.57 | |||

| A: ARG199:HH22-A: SER59:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.57678 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:HH22 | H-Donor | A: SER59:O | H-Acceptor | 110.754 | 101.967 | |||

| A: GLN202:HE22-A: GLU62:OE1 | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.73138 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: GLN202:HE22 | H-Donor | A: GLU62:OE1 | H-Acceptor | 108.417 | 144.232 | |||

| A: ARG28:HH21-A: ASN340:O | Yes | 0 255 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.77325 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG28:HH21 | H-Donor | A: ASN340:O | H-Acceptor | 101.182 | 111.394 | |||

| A: THR66:CA-A: GLU143:OE2 | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.04656 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-Hydrogen Bond | A: THR66:CA | H-Donor | A: GLU143:OE2 | H-Acceptor | 97.175 | 133.466 | |||

| A: ARG199:CD-A: ASN19:O | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 2.93401 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-Hydrogen Bond | A: ARG199:CD | H-Donor | A: ASN19:O | H-Acceptor | 109.071 | 136.47 | |||

| A: PRO25:CD-A: GLY325:O | Yes | 220 255 220 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.23162 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon-Hydrogen Bond | A: PRO25:CD | H-Donor | A: GLY325:O | H-Acceptor | 101.133 | 159.832 | |||

| A: ARG186:NH2-A: PHE142 | Yes | 255 150 0 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.52237 | Electrostatic | Pi-Cation | A: ARG186:NH2 | Positive | A: PHE142 | Pi-Orbitals | 39.679 | ||||

| A: PRO67-A: LYS18 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.62908 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: PRO67 | Alkyl | A: LYS18 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: PRO234-A: PRO25 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.44989 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: PRO234 | Alkyl | A: PRO25 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: PRO25-A: LEU329 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 3.40277 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: PRO25 | Alkyl | A: LEU329 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: LYS173-A: LEU329 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 4.61158 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | A: LYS173 | Alkyl | A: LEU329 | Alkyl | |||||

| A: PHE142-A: MET326 | No | 255 200 255 | Non-bond Monitor 1 | 5.29592 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | A: PHE142 | Pi-Orbitals | A: MET326 | Alkyl |

A comparative docking analysis was conducted between the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein from Tecticornia indica and the standard anticancer drug Tamoxifen, which was used as a control to evaluate the anticancer potential of the plant-derived protein.

The results demonstrated that ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase exhibited stronger binding affinities (i. e., more negative binding energies) in comparison to Tamoxifen when docked with both DHFR and EGFR (table 9). These findings suggest that the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein may possess superior inhibitory potential against key cancer-related targets.

Based on these results, it can be proposed that ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Tecticornia indica holds promise as a natural anticancer agent, potentially offering an effective and plant-based alternative to conventional chemotherapy drugs such as Tamoxifen.

Table 9: Comparing the binding features of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and Tamoxifen drug

| Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase. | Tamoxifen drug (control). | |

| DHFR | -1019.9 | -504.3 |

| EGFR | -892.4 | -629.1 |

DISCUSSION

The interaction between ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO) and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) was investigated using protein-protein docking via the ClusPro server. The results suggest that RuBisCO exhibits promising potential as an inhibitor of DHFR, a well-established target in cancer therapy. Similar findings were reported by Yue Meng (2023) [14], supporting the hypothesis that RuBisCO could serve as a functional modulator of DHFR.

Previous computational analyses have examined conformational changes, binding affinities, and the interaction of RuBisCO with various inhibitors under physiological conditions, including the presence of CO₂ and H₂O. Notably, xylulose-1,5-bisphosphate (XuBP) has been identified as an endogenous inhibitor that binds the active site of RuBisCO, reducing its catalytic efficiency [15]. In our study, the docking results demonstrated a low binding energy configuration between RuBisCO and DHFR, suggesting spontaneous and energetically favorable binding. These negative binding energies reinforce the potential inhibitory activity of RuBisCO, proposing its candidacy as a natural anticancer agent through the inhibition of DHFR activity.

Since DHFR plays a crucial role in nucleotide biosynthesis and cell proliferation, it is considered an essential enzyme in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. Thus, it continues to attract attention as a molecular target in anticancer drug discovery [16].

In a parallel docking study, RuBisCO also demonstrated strong binding affinity toward the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). EGFR is a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase family and is known to be overexpressed in various malignancies, including ovarian, prostate, breast, bladder, lung, and colon cancers [18]. The negative binding energies observed in the docking analysis further support the favorable interaction of RuBisCO with EGFR, suggesting a dual inhibitory potential against both DHFR and EGFR.

For comparison, the binding properties of Tamoxifen, a widely used anticancer drug, were also evaluated against both DHFR and EGFR. Tamoxifen primarily functions as a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), and is most effective in treating ER+ and PR+ breast cancers [19]. Tamoxifen and similar compounds have also been shown to target DHFR in various studies [20].

However, our docking data indicate that RuBisCO demonstrated more negative binding energies compared to Tamoxifen for both targets. While Tamoxifen remains a clinically validated and effective agent, RuBisCO’s superior binding affinity indicates it may serve as a potential alternative or complementary molecule in anticancer therapy.

This comparative analysis sheds light on the therapeutic promise of RuBisCO, not only as a candidate inhibitor of cancer-related proteins but also as a target for further structural and functional studies. Given the growing interest in plant-derived natural compounds for cancer treatment, RuBisCO represents a compelling subject for further preclinical investigation.

Our study emphasizes the utility of protein-protein docking in uncovering novel anticancer compounds and highlights the potential of RuBisCO as a natural inhibitor of DHFR and EGFR. The findings support future in vitro and in vivo validation to assess RuBisCO’s efficacy and mechanism of action in cancer models.

CONCLUSION

In this study, marine plant Tecticornia indica has been found to possess anticancer property against DHFR and EGFR. It was carried out using the Clus-Pro software for protein-protein docking, and the binding energies of Tamoxifen and Tecticornia indica were compared. (GenBank: AAQ75644.1) Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein from Tecticornia indica has been used for generating a model. The Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and Tamoxifen drug (control)were docked with DHFR and EGFR, respectively. DHFR is one of the common targets for the treatment of several illnesses, including cancer. Similarly, Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Tecticornia indica has been found as a candidate molecule that can inhibit DHFR and EGFR based on the negative binding energy.

Tamoxifen drug, when used as a control to compare its efficiency with ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase protein of Tecticornia indica, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase has been found to be effective as an anti-cancer. Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase has higher binding energy in comparison to the Tamoxifen drug. We can say that Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase can be used as an anti-cancers medicine.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Bhakti Mhatre designed the experimental work, reviewed the manuscript, and improved the quality of the manuscript. Dr. Pramod Kumar Gupta carried out all docking study, Ms Tanvi Sarang carried out all the laboratory work and data collections.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Rabhi M, Castagna A, Remorini D, Scattino C, Smaoui A, Ranieri A. Photosynthetic responses to salinity in two obligate halophytes: Sesuvium portulacastrum and Tecticornia indica. S Afr J Bot. 2012;79:39-47. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2011.11.007.

Mahlo SM, Chauke HR, McGaw L, Eloff J. Antioxidant and antifungal activity of selected medicinal plant extracts against phytopathogenic fungi. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2016;13(4):216-22. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v13i4.28.

Abu Hafsa SH, Khalel MS, El Gindy YM, Hassan AA. Nutritional potential of marine and freshwater algae as dietary supplements for growing rabbits. Ital J Anim Sci. 2021;20(1):784-93. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2021.1928557.

Overland M, Mydland LT, Skrede A. Marine macroalgae as sources of protein and bioactive compounds in feed for monogastric animals. J Sci Food Agric. 2019;99(1):13-24. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9143.

Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Phcog Rev. 2010;4(8):118-26. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902.

Srivarathan SA, Phan AD, Hong HT, Chua ET, Wright O, Sultanbawa Y. Tecticornia sp. (Samphire) a promising underutilized Australian indigenous edible halophyte. Front Nutr. 2021 Feb;8:607799. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.607799.

Dewanji A, Chanda S, Si L, Barik S, Matai S. Extractability and nutritional value of leaf protein from tropical aquatic plants. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1997;50(4):349-57. doi: 10.1007/BF02436081.

Barua CC. Nutritional evaluation of few selected medicinal plants. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):539-47.

Wemegah JT. Nutritional composition of aquatic plants and their potential for use as animal feed: a case study of the Lower Volta Basin, Ghana. Biofarmasi Biochemist Nat J Producer. 2018;16(2):99-112. doi: 10.13057/biofar/f160205.

Sansone C, Brunet C. Marine algal antioxidants. Antioxidants. 2020;9(3):206. doi: 10.3390/antiox9030206.

Preethi HK, Vishal B. Overview of mitoxantrone a potential candidate for treatment of breast. Int J App Pharm. 2022;14(2):10-22. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2022v14i2.43474.

Mohamed AS, Mohamed DM, Irfan N. Biochemical evaluation of Indus Viva I Pulse Natural Ayurvedic Syrup and it’s in silico interaction analysis. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(12):31-42. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i12.49266.

Kunal R, Sachin K, Vishal P. Design of potent anticancer molecules comprising pyrazolyl thiazolinone analogs using molecular modelling studies for pharmacophore optimization. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(8):85-93. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i8.47665.

Meng Y, Liu R, Wang L, Li F, Tian Y, Lu H. Binding affinity and conformational change predictions for a series of inhibitors with RuBisCO in a carbon dioxide gas and water environment by multiple computational methods. J Mol Liq. 2023 Apr 15;376:121478. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2023.121478.

Pasch V, Leister D, Ruhle T. Synergistic role of RuBisCO inhibitor release and degradation in photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2025;245(4):1496-511. doi: 10.1111/nph.20317.

Sehrawat R, Rathee P, Khatkar S, Akkol E, Khayatkashani M, Nabavi SM. Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitors: a comprehensive review. CMC. 2024;31(7):799-824. doi: 10.2174/0929867330666230310091510.

Nasab RN, Mansourian M, Hassanzadeh F, Shahlaei M. Exploring the interaction between epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase and some of the synthesized inhibitors using combination of in silico and in vitro cytotoxicity methods. Res Pharma Sci. 2018;13(6):509-22. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.245963.

Shikov AN, Flisyuk EV, Obluchinskaya ED, Pozharitskaya ON. Pharmacokinetics of marine-derived drugs. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(11):557. doi: 10.3390/md18110557.

Alex MJ. Docking studies on anticancer drugs for breast cancer using hex. In: Proceedings of the International Multi Conference of Engineers and Computer Scientists; 2009;1:18-20.

Mhatre B, Gupta PP, Marar T. Evaluation of drug candidature of some anthraquinones from Morinda citrifolia L. as inhibitor of human dihydrofolate reductase enzyme: molecular docking and in silico studies. Comp Toxicol. 2017;1:33-8. doi: 10.1016/j.comtox.2016.12.001.