Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 7, 1-8Review Article

PHARMACEUTICAL POLYMERS IN DRUG DELIVERY: AN OVERVIEW

RANU BISWAS*, PRITAM KAPAT, ARINDAM GHOSH, SHOUNAK SARKHEL, TANIMA SARKAR, DIPANKAR DAS

Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata-32, WB, India

*Corresponding author: Ranu Biswas; *Email: rbiswas.pharmacy@jadavpuruniversity.in

Received: 07 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 09 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Polymers have significantly assisted to the advancement of the drug delivery devices by adjusting the drug release at consistent rates over extended durations, facilitating cyclic administration, and targeting to the desired site. Polymers are frequently utilized as taste-masking, stabilizing, and proactive agents. The key characteristics that render polymers appealing options for drug delivery include their safety, effectiveness, hydrophilicity, non-immunogenicity, biological inertness, favourable pharmaceutical kinetics, and the presence of functional groups that facilitate covalent crosslinking, targeting ligands, or copolymer formation. Natural polymers that are more commonly used, like arginine, collagen, chitosan, and carrageenans are discussed for their possible application in polymeric drug delivery systems. Synthetic polymers exhibit elevated immunogenicity, limiting their viability for prolonged application. Non-biodegradable polymers necessitate subsequent removal post-drug release at the intended site. Progress in polymer science has made possible in the emergence of various innovative drug delivery systems, including hydrogels, liposomes, nanoparticles, micelles, patches, implants, and others. Biodegradable polymers have garnered considerable interest because they can degrade into non-toxic monomers, enabling sustained drug release from biodegradable polymer-based controlled-release devices. This review delves into the commonly used synthetic and natural polymers that are used in drug delivery, consideration of selection of polymers and recent advancement in polymer research.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical polymers, Biodegradable polymers, Polysaccharides, Drug delivery

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i7.54498 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

The term "polymer" originated from a Greek word which signifies "multiple components [1]. Polymers are compounds consisting of a large number of units that constantly repeat itself that are compacted into molecules with high molar weights. Polymers possess the capacity to generate solid dosage form particles as well as modify the flow characteristics of liquid dosage forms [2]. Due to their special qualities that no other material can match, polymers are used extensively in the delivery of pharmaceuticals. Polyglycolic acid was the first synthetic polymer that was introduced for drug delivery purposes, and this increased interest in the production and design of biodegradable polymers [3]. Polymers can be manmade or naturally occurring. Proteins, starches, latex, and cellulose are some of the naturally occurring polymers. They are usually employed as taste-making, stabilizing, and proactive agents. They have an extended half-life than conventional medication molecules, which allows them to target tissue more precisely. Polymers have made great strides in reservoir-based drug delivery systems such as hydrogels and liposomes [4]. These are also integrated into polymer matrix. Factors including the kind of polymer matrix, the geometry of the matrix, the characteristics of the drug, the early loading of the drug, and the drug-matrix relationship, affect the drug release from such system [5]. Applications for polymers in biomedical sciences includes prosthetics, ophthalmology, dentistry, bone healing, implanting medical devices, artificial organs, and scaffold development in tissue engineering [6]. Responsive polymers adjust to fluctuations in temperature, pressure, pH, and various other factors, making them particularly effective for the precise delivery of drugs. Certain polymeric systems coupled to certain biomarkers or antibodies aid in the identification of molecular targets unique to malignancies [5]. The advancement of technology, including the chemical modification of pharmaceuticals, carrier-based drug delivery systems, and the entrapment of drugs in polymeric matrices or pumps, has greatly improved the efficacy of medication therapy, thereby benefiting human health. Given the abundance polymers available, our objective is to discuss about the commonly used polymers, and also addresses the different factors to be taken when choosing polymers for drug delivery applications [7].

All the data and information are collected from Science Direct, springer, Google Scholar, PubMed, Research Gate and other databases. These data and information are collected by using the following keywords like polymers, drug delivery, carriers, chitosan, biodegradable polymers, controlled release, targeted drug delivery, pharmaceutical excipients, biopolymers, smart polymers, bioresponsive polymers and natural polymers etc. The entire search was made from 2010 to 2024, which makes this review updated and comprehensive.

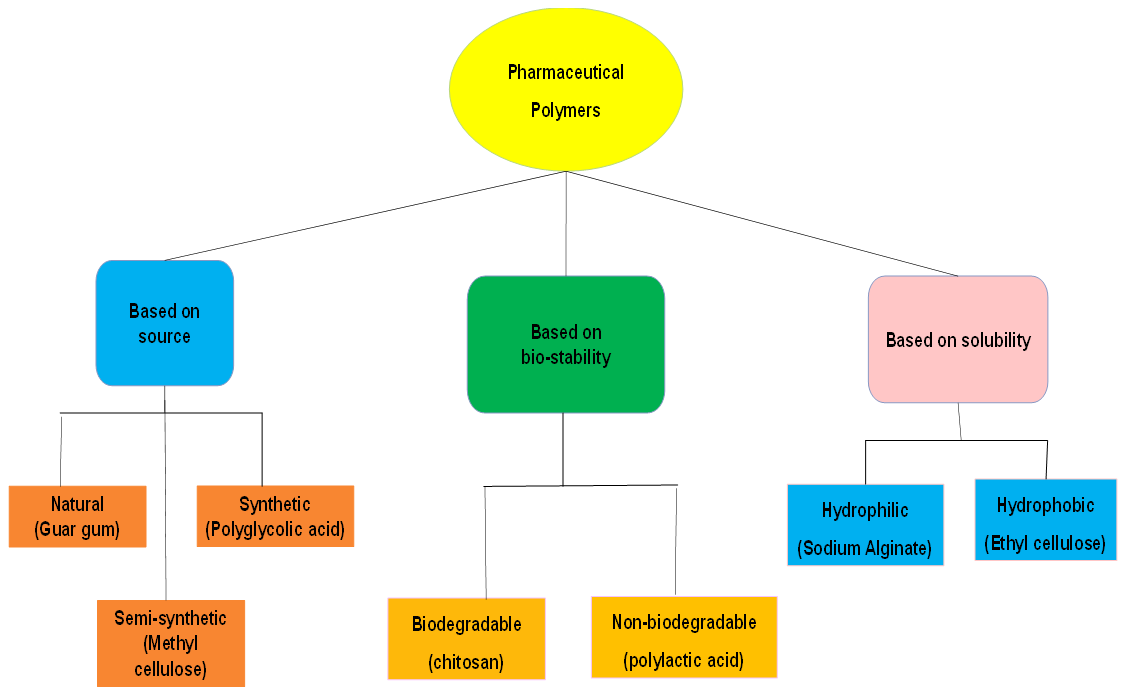

Classification of polymers used in drug delivery

Most widely used polymers in drug delivery systems are categorised based on their source, bio-stability and solubility (fig. 1) [7].

Most commonly used pharmaceutical polymers

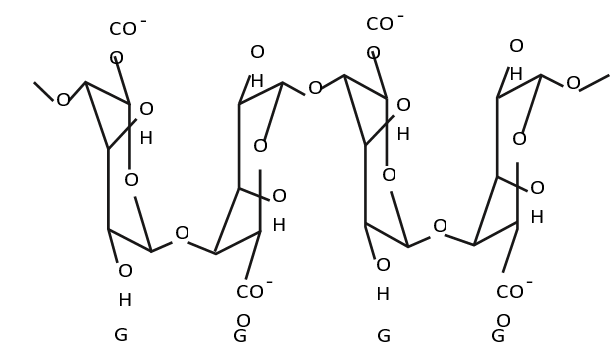

Alginate

The common sources of the polysaccharide alginate include Laminaria hyperborea, Laminaria digitata, Laminaria japonica. It is a biodegradable polymer with very low cytotoxicity that is frequently employed in formulations as an excipient or a stabilizer. Because alginate contains COOH groups at pH greater than 3–4 it shows solubility in neutral and basic environments. Alginate hydrogels are used in the manufacturing of wound dressings as part of wound healing therapy. Alginate hydrogels are also frequently utilized in cell encapsulation and tissue regeneration procedures [8]. Konwarh et al. used alginate for utilizing alginate-based nanocomposites as platforms for delivering genes and nucleic acids to address a range of biological problems [9]. Alginates have proven useful in nanomedicines for a number of applications, including solid lipid nanoparticles, micelles, liposomes, dendrimers, nanocrystals, emulsions, and polymeric nanoparticles [8]. Duong et al. used alginate to study alginate aerogels using spray gelation to improve beclomethasone dipropionate solubilization and pulmonary administration [10].

Fig. 1: Classification of polymers

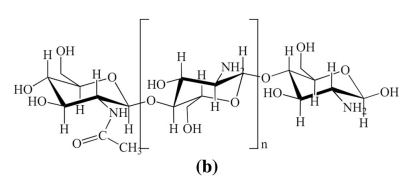

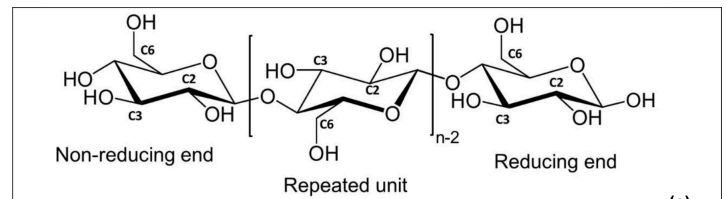

Chitosan

Chitosan is a promising natural organic versatile biopolymer. It has been widely used in pharmaceutical, biomedical, cosmetics and food industries due its biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity and widespread availability [11]. Shrimp, crab, and lobster shells contain chitin, which is the source of chitosan. Chitosan can be utilized as a disintegrant, tablet coating, parenteral formulation delivery platform, drug carrier, and tablet excipient [12]. Rahaman et al. designed polymer-prodrug nanomicelles containing succinyl curcumin conjugated chitosan for controlled release of curcumin for effective management of Type-II diabetes [13]. Lucero et al. used chitosan to study innovative aqueous chitosan-based dispersions as excellent drug delivery techniques for topical application. Chitosan has the ability to facilitate the administration of chemotherapeutics, including antibiotics, antiparasitics, anesthetics, pain relievers, and growth promotants, in the veterinary field. Protonated chitosan can boost the paracellular accessibility of peptide, carboxymethyl derivative provides gelling qualities, whereas the trimethyl derivative improves the permeability of neutral and cationic peptide counterparts. Additionally, nonionic surfactants such as sorbitan esters can be used with chitosan to form emulsions or creams. Hongdan et al. used chitosan to study the possible application of innovative deformable liposomes covered with chitosan in a medicine delivery system for the eyes [14].

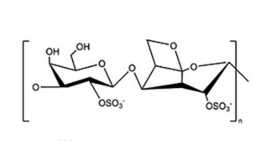

Carrageenan

Carrageenan is extracted from certain red seaweed species that are from the Rhodophyceae family, namely Chondrus crispusspp. The three fundamental forms of carrageenan are λ-type, ι-type and κ-type. The λ-type produces viscous solutions but does not gel, in contrast to the κ-type carrageenan, which forms a crumbly gel. Elastic gels are produced by the γ-type. A combination of crosslinked alginate and κ-carrageenan with potassium and calcium was used to create hydrogel beads. The hydrogel's carrageenan components significantly improved the polymeric network's thermostability [15]. Sagil et al. used carrageenan to study on calcium alginate, gelatin, and κ-carrageenan composite hydrogel combination for 3D bioprinting [16].

Polylactic acid

Polylactic acid (PLA) is made of renewable resources like sugarcane or tapioca roots, chips, or starch as well as corn starch. By changing PLA's stereochemistry, one may change its mechanical, thermal, and biological characteristics [2, 3]. It is considered to be the perfect material for medication delivery systems that are microencapsulated. PLA is a great option for regulated drug administration in parenteral preparations because of a variety of advantages, including as biological degradation and biological compatibility. With respect to their PLGA equivalents, PLA parenteral microparticle compositions were shown to have prolonged drug release behaviour. Furthermore, depending on the PLA's molecular weight, microparticle size, drug loading, dissolution capacity, and diffusing ability, drug release rates may be regulated by PLA microparticles for a variety of durations, ranging from a few days to several months up to a year [17]. Farnaz-sadat et al. used polylactic acid to study on a scientific perspective on polylactic acid nanoparticle synthesis for novel therapeutic applications [18].

Poly (glycolic acid) (PGA)

It is an aliphatic polyester and a thermoplastic polymer that is biodegradable. PGA has been frequently employed as absorbable sutures. PGA can be eliminated through regular metabolic routes, making it a useful material for medication administration. PGA has been recognized as a desirable alternative for transplant cells in a range of configurations, including fibergrids. It has been discovered that PGA has a low resistance to compressional stresses. PGA is a good material for internal fixation devices for bones. PGA is also commonly used material for biodegradable stents [19]. Alastair et al. used Poly(glycolic acid) to investigate the creation and assessment of Poly(adipate-co-butylene terephthalate) and Poly(glycolic acid-co-butylene succinate) copolymers with elevated glycolic acid content and improved elasticity[20].

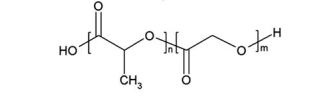

Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA)

It has applications both in drug delivery and tissue engineering. For targeting, visualizing, and therapy, PLGA Nano Structures (NS) offer enormous promise. PLGA has drawn a lot of attention due to its notable qualities, which include aqueous degradation, biological degradation and biological compatibility, drug delivery systems approved by European Medicine Agency and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), can be easily modified into sustained release, and effective biological interactions, defence against drug deterioration, well-described synthesis methods and preparations for hydrophilic or hydrophobic macromolecules or small compounds, potential to target certain cells or organs. Currently, FDA-authorized biodegradable polymeric nano drug delivery systems are developed using PLGA. It can be made into micro and nanoparticles, which enhance their interactions with biological materials [21]. Lu et al. used PLGA to study the significance of the production and the composition affecting the mechanical strength and penetration in PLGA nanoparticle-facilitated drug delivery in microneedles [22]. Additionally, in order to reach certain tissues or cells, they can bind with particular target proteins. It can be used in vaccinations and therapies for neurological conditions, cancer, inflammation, and other illnesses [23]. Malihe et al. used PLGA to study the latest advances in PLGA-based microfibers as anticancer drug delivery techniques [24].

Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC)

It is a linear polymer made from anhydrous glucose that is an aqueous, ionic derivative of cellulose. They are valuable in many different industries, including medical, pharmaceutical products, fabrics, nutrition, building, plastics, beauty products, paper, and oil, because of their readily available basic components, distinctive surface properties, low cost of synthesis, and adaptability. For example, CMC and its analogs are widely employed in the medical industry for a variety of purposes, such as surgical dressings, tissue engineering, bone-tissue engineering, the creation of 3D scaffolds for biocompatible implants, prosthetic organs, or replicas of the external polymeric network. Particularly for drug delivery, drug emulsification, and stabilization applications, the outstanding biological compatibility, excellent stability, pH sensitivity, and binding capability of CMC-based materials have drawn a lot of interest [25]. Nádia et al. used carboxymethyl cellulose to study crosslinked hydrogels of superabsorbent carboxymethyl cellulose-PEG for possible use as wound dressings [26]. Sujie et al. used carboxymethyl cellulose to study the development of carboxymethyl cellulose aerogels for use as a drug delivery system [27].

a b

c d

e f

Fig. 2: Chemical structure of a) alginate b) Chitosan c) Carrageenan d) PLGA e) HPMC f) CMC [8, 13, 15, 21, 25, 28]

Hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC)

Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose is a free-flowing, fibrous or granular, white powder with no flavour or odour. Its extensive acceptance can be linked to several factors, including (1) The ability to dissolve in aqueous and organic solvent systems, as well as in GI fluid; (2) the film's no impact on tablet breakdown and drug accessibility; (3) its durability against chips, flexibility, and taste or odor; (4) its ability to hold up when exposed to sunlight, heated air, or moderate moisture; and (5) Its ease in adding color and other ingredients. Because of these characteristics of HPMC, it’s applicability to the dietary supplementsas binders, emulsion and foam stabilizers, fat substitutes, non-caloric bulking agents, oil barriers, and moisture retainers [28, 29]. Chen et al. used hydroxypropyl methylcellulose to study the creation of a sticky film for the buccal mucosa that is made using an interpolymer mixture of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and polyacrylic acid to aid in the delivery of insulin for the treatment of diabetes. It has a very low order of toxicity [30].

Ethyl cellulose (EC)

EC, cellulose derivative, is a versatile polymer as it has no smell, melting point 240-255 C, specific density 1.07 to 1.18 and a fire point of 330-360 C, soluble in numerous organic solvents, such as ketone, ester, etc but insoluble in water, biocompatible, stable to heat, light, oxygen, moisture, and chemicals, non-irritating, non-toxic, used as a tablet binder to give particles plastic flow characteristics. EC can be used to protect drugs against oxidation, hydrolysis, and active interactions. Additionally, it is used as a coating agent or matrix for extended-release [31]. Michael et al. used ethyl cellulose examined the use of ethyl cellulose for temperature-responsive drug administration by using biocompatible fatty acids as phase transition materials in ethyl cellulose nanofibers [32]. EC can be utilized in formulations for transdermal, ophthalmic, vaginal applications, among other external applications. Drug dosage forms with prolonged release, including hydrogels, inserts, contact lenses, or minitablets, are created to increase intraocular bioavailability [33].

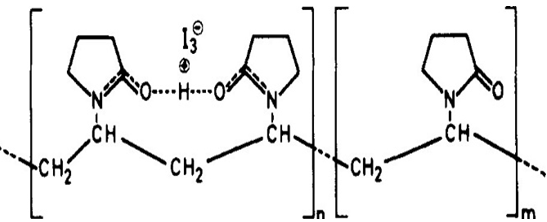

Polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP)

It is a hydrophilic polymer that has outstanding binding qualities, excellent solubility in polar solvents, and a stabilizing influence on suspensions and emulsions. PVP has unique physical as well as chemical characteristics, including being primarily chemically inert, pH-stable, temperature-resistant, and colourless. It has been used to develop a range of drug delivery techniques, such as oral, topical, transdermal, and ocular administration, in the pharmaceutical and biomedical industries [34]. Sammour et al. used polyvinyl pyrrolidone to study on production and upgrading of pills that dissolve in the mouth containing rofecoxib solid dispersion [35]. In addition, PVP can be combined with metal particles for targeted delivery or used in gene delivery for regenerative medicine. Borji et al. developed Polyvinyl Pyrrolidone/Starch/Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposite for targetted delivery of Doxorubicin in Cancer Therapy [36].

Xanthan gum

Xanthan gum (XG) is natural exogenous heteropolysaccharide and fermentation byproduct of the g-negative, aerobic pathogen Xanthomonas campestris. It is water soluble and one amongst the most important commercially available microbial polysaccharides. It serves as a potent thickening agent that enhances the stability of emulsions in the food and cosmetics sectors. For the extended-release of pharmaceuticals, XG is considered an active excipient. A carrier system called XG is used to transfer genes, proteins, and drugs. Improved and characterized multiparticulate formulation based on xanthan gum for colon targeting was studied by Koteswara et al. using xanthan gum. It has two key features: (i) stable at low pH, preventing drug degradation in gastric fluid, and (ii) the capacity to modify both the ionic and pH strength of the dissolution medium in order to control the speed at which the drug is released. It is currently used as hydrogels, microspheres, tablets, and mucoadhesive gels [37]. Singnorini et al. prepared polymeric micelles using crosslinked xanthan gum as a sterile platform for delivering neuroprotective drugs to the posterior segment of the eye [38].

a b

c d

e f

g

Fig. 3: Chemical structure of a) Polyvinyl pyrrolidone b) Ethyl cellulose c) Xanthan gum d) Guar gum e) Eudragit f) Cyclodextrin g) Cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) [31, 34, 39, 42, 45]

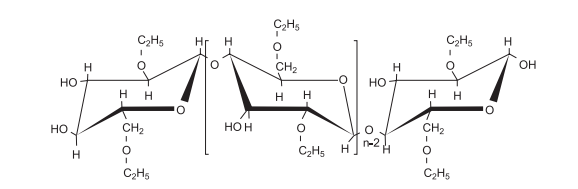

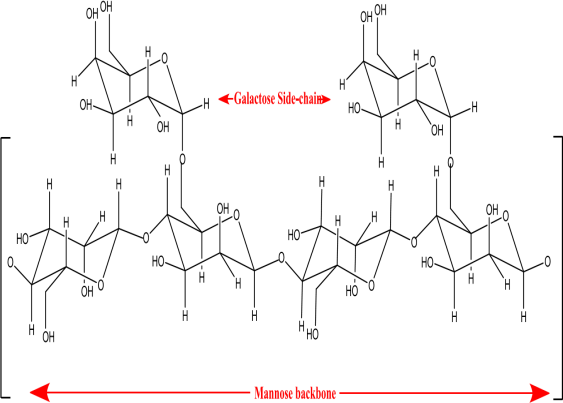

Guar gum

It is one of the most affordable sources of galactomannan. It is a hydrophilic carbohydrate polymer that is non-ionic. It is soluble in water and is non-ionic. It has been employed as a vehicle for colon targeting and oral drug delivery investigations. By cross-linking polyethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (PEGDGE) with polymer chains, the researchers created GG hydrogel. GG hydrogel's suitability for use as a drug delivery device has been demonstrated by rheological research and in vitro release tests [39]. Zarbab et al. developed guar gum-based biopolymeric hydrogels as vehicles for the controlled delivery of methotrexate in the treatment of colon cancer [40]. Roy et al. investigated the creation and assessment of carboxymethyl guar gum-chitosan interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) nanoparticles for the regulated administration of drugs using guar gum [41].

Eudragit

Eudragit is based on acrylic acid and its derivatives. It has been used to GI targeting, enteric coatings, pulsed release, transdermal formulations, film coating, granulation, direct compression, melt extrusion, and technical mastery to manufacture instant or sustained release [42]. Furuishi et al. formulated transdermal drug delivery system using Eudragit® E adhesive and an innovative eptazocine salt [43]. There are different grades of Eudragit, like Eudragit E100, E12.5 and EPO. Low viscosity, strong pigment coupling ability, good adherence, and minimal polymer weight growth are some of their qualities. They are frequently employed in moisture and light protection, film coating, and taste and odor masking. Eudragit E 100 has been utilized in transdermal spray, ophthalmic solution, floating drug delivery systems, and nanoparticles. Eudragit L100 has been employed in various formulations, such as microspheres, nanoparticles, liposomes etc for enteric coating, sustain release, insulin permeation, bioavailability enhancement etc [42]. Anwar et al. used eudragit to prepare hydrogel that would allow for the regulated release of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs to treat wound infections [44].

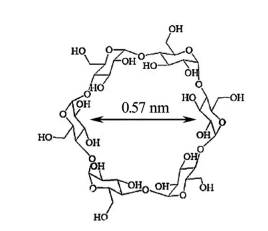

Cyclodextrins (CDs)

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are prepared by the enzymatic breakdown of starch. CDs have an exterior surface that is hydrophilic and an interior chamber that is somewhat hydrophobic. It has two possible uses: 1) they can act as hosts when lipophilic substances, such as medicines, small molecules, and polymers, combine to create inclusion complexes (ICs); and 2) they can operate as active building blocks when creating functional materials. In order to provide stimuli that are responsive and tailored drug-release behavior, pharmaceuticals can be grafted into the hydroxy groups of CDs employing stimuli-responsive linkages in cyclodextrin-based polyrotaxane. By precisely regulating CDPs' molecular weight and hydrophilic-hydrophobic ratio, they may also self-assemble into vesicles and micelles [45]. Pineli et al. used cyclodextrin to study agarose-based hydrogels functionalized with β-cyclodextrin for various regulated medication delivery of ibuprofen [46].

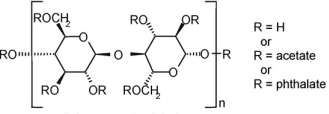

Cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP)

Ethers and ester derivatives of cellulose have been crucial in developing sustained, controlled-release oral dosages because they can be used as hydrophobic matrices that slow down the rate at which the active drug dissolves; they can act as a barrier that can aids in sustained release and coatings that can adapt to alterations in the physiological environment. CAP is non-toxic, water-soluble, and economical [47]. For decades, enteric-coated of oral formulations has been accomplished using cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP), an FDA-approved polymer that is physiologically inert and permits drug release in the more basic environment of the intestine while preventing premature drug release in the stomach which is acidic. The ionizable phthalate group is the reason of CAP's pH dependency [48]. Hua et al. developed pH-responsive electrospun fiber consisting of cellulose acetate phthalate (shell) and polyurethane (core) for intravaginal delivery of drug [49]. The discovery that CAP interferes with Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 (HIV-1), Herpes Simplex Virus-1 (HSV-1), and Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-2) virility suggests that it may find application as a topical microbicide. It was recently demonstrated that CAP possesses strong antiviral properties against pathogenic microorganisms, a variety of HIV clades and subtypes, herpes virus, and SIV. Reshmi et al. investigated the formation, characterization, and dielectric studies of carbonyl iron/cellulose acetate hydrogen phthalate core/shell nanoparticles for possible medicinal uses using cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) [50].

Biomimetic and bio-inspired polymers

When it comes to drug delivery, biomimetic and bioinspired systems enhance biocompatibility. Certain elements, like as form, surface, texture, movement, and preparation techniques, are critical to the efficacy of such a drug delivery device. Because of their significant interaction, high biocompatibility, low toxicity, and other qualities, the systems have a significant impact on biological systems. The innovative advancements in dendritic polymers-based targeted micro-scale drug delivery carriers that are presented here offer a great deal of promise for improving therapeutic indices and minimizing adverse effects in cancer treatment. Kulshrestha et al. designed polyaniline's bioinspired organizational framework serves as a pH-sensitive smart material on the porous surface of polymer films through interfacial polymerization. Regardless of the development of artificial carriers for drugs, it is still necessary to investigate natural particulates, which include pathogens and the mechanisms of mammalian cells. Because of their special chemical and physical characteristics, biocompatible polymeric nanoparticles are extremely attractive carrier candidates for the transport of genes and medications [51]. Men et al. used biomimetic polymers to study on high specificity Near-Infrared (NIR-II) fluorescence visualization of gliomas using biomimetic semiconducting polymer nanoparticles [52].

Responsive polymers

A family of materials known as environmentally-responsive polymers are made up of a wide range of conjugated polymer array. The ability of responsive polymers to dramatically alter physically or chemically in accordance to external stimuli is one of their distinguishing characteristics. While temperature, as well as pH alterations, are frequently employed to induce behavioural shifts, other triggers can also be employed, including ultrasound, electromagnetic radiation, and biochemical agents. Lee et al. used responsive polymers to develop targeted and stimuli-responsive drug delivery using cellulose nanocrystals adorned with a functional polymeric Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) nanostructure [53]. These stimuli fall into distinct categories that are: i) Physical stimuli that have the ability to directly alter the energy level of the solvent/polymer system and trigger a polymer reaction at a critical energy level. These stimuli include things like light, magnetic and electrical fields, temperature, and ultrasonic waves. ii) The chemical stimuli include ionic strength, pH, redox potential, and chemical agents that can change the molecular binding between a polymer and solvent, changing the water-loving (hydrophilic)/water-hating (hydrophobic) balance or between polymer chains, which can affect the tendency for hydrophobic interactions, the electrostatic repellent effect, or structural integrity [5].

Smart polymers

These are excellent performer polymers that adjust to their living circumstances. The characteristics of the polymer can alter significantly in accordance with slight environmental changes. In reaction to pH changes, they can alter their conformation, adhesiveness, and water retention qualities. They are employed in the creation of many materials, including hydrogels. Crosslinking pH-sensitive smart polymeric chains gives rise to formation of smart polymers. The cross-linking density and the solute's permeability are inversely connected; the higher the cross-linking density, the lower the permeability. Alginate gel beads with a physiologically active substance co-precipitate to produce gels with extended-release. This offers the advantage of a high drug loading and enhances protein stability. One particular polymer that has been studied for the control of drug delivery networks is LCST. By fortifying its mechanical properties, copolymerization with alkyl methacrylates preserves N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAAm's) temperature sensitivity. The mobility of the bioactive molecules out of the polymers is decreased by thickly coating the LCST with poly NIPAAm polymer [4]. Ullah et al. used smart polymers to design a pH-responsive polymer-coated microneedle array in intelligent medication delivery for wound healing [54].

Consideration for the selection of polymers in drug delivery

Due to diverse structure selecting and developing a polymer may be challenging and necessitate a thorough understanding of the material's bulk and surface characteristics in order to deliver the required physical, chemical and biological functions. The choice of a polymer depends not only on its physico-chemical properties but also on the need for detailed biochemical analysis and specific preclinical research to confirm its safety. The surface properties of the polymers also affect their capacity to absorb water. However, materials intended for long-term use, such as dental and orthopedic implants, need to be water-repellent in order to prevent deterioration or erosion processes that result in changes to the material's toughness and mechanical strength. Bulk factors, including molecular weight, adhesion, solubility based on the release process, and the region of action, must be considered for controlled delivery systems. While polymers for ocular devices must be hydrophilic or lipophilic in addition to having strong film-forming ability and structural stability. It is important to realize that, in the case of biodegradable polymers, erosion is something that is dependent on the processes of dissolution and diffusion, while degradation is a chemical process. The type of erosion that occurs whether surface erosion or bulk erosion depends on the molecular structure of the polymer backbone. Because of its extremely reproducible kinetics of erosion and drug release (zero order), surface erosion is desired. By altering the DDS's surface area or including hydrophobic monomer units into the polymer, the erosion process may be managed. Numerous polymer topologies, such as linear, branching, star-like, or comb-like polymers, as well as mix of polymer species that are chemically bound (copolymers) or physically combined (polymer blends or interpenetrating networks), provide an enormous amount of flexibility as delivery methods. While choosing the right polymers is crucial, particularly in terms of their compatibility with the medication, the production process must also be taken into account because the additives used during polymerization have the potential to destroy the drug. Although natural polymers are often biodegradable and provide excellent biocompatibility, their purification challenges lead to batch-to-batch variation. Conversely, synthetic polymers come in an extensive range of compositions and easily customizable qualities [3, 7].

Current thrust in drug delivery

Molecularly imprinted polymers

In the intriguing field of molecular imprinting, specialized polymer networks are engineered to selectively recognize a specific target molecule. This process involves selecting functional monomers that can interact with the target through either covalent or noncovalent bonds. During polymerization, the target template is integrated with the monomers, and after the template is extracted, a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) is created, which contains binding sites specifically designed for the template molecule. This method presents considerable benefits compared to traditional drug delivery systems, allowing for a zero-order release of medication over prolonged durations. As a result, there is no longer a need for frequent high-dose treatments since the optimal MIP drug delivery system (DDS) can sustain the medication concentration within its therapeutic range. Given the drawbacks of conventional methods, such as low bioavailability (~5%), the requirement for frequent high doses, short-term discomfort, and vision impairment, the ocular route emerges as a promising application for MIPs. By utilizing the enhanced interaction between the drug and the polymer's functional groups, MIPs can effectively tackle issues like improved bioavailability, extended retention times, and the maintenance of therapeutic levels by moderating the release rate [5].

Endosmolytic polymers

Carriers are essential for guiding sensitive molecules to their designated sites of action. The emergence of highly targeted biological agents, including proteins like enzymes, hormones, monoclonal antibodies, nucleic acids such as plasmid DNA, antisense oligonucleotides, and small interfering RNA (siRNA), underscores this necessity. The delivery of this delicate therapeutics faces significant challenges due to both extracellular and intracellular trafficking barriers, which calls for innovative approaches. As a result, there has been an increase in the creation of biomimetic polymers aimed at mimicking the membrane-disrupting properties of toxins and viruses that contain fusogenic peptides. Recent systematic research has illuminated the factors that affect membrane interactions, indicating that the characteristics of polymers, such as their composition, surface charge, hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance, and functional group distribution play a crucial role in their interactions with cell membranes and their overall endosomolytic effectiveness [5].

Future prospects

An area of research that is advancing rapidly is the creation of drug-delivery vehicles using synthetic and natural polymers. The field of responsive delivery systems is where the most significant progress in polymeric drug delivery is occurring, facilitating the targeted administration of drugs based on specific locations or blood level readings. The researchers foresee various applications for these copolymers, such as lining artificial organs, conducting immunology tests, and serving as drug-targeting agents, functioning in chemical reactors, and providing substrates for cell growth [2]. With the use of a specific polymeric system, implanted devices may be developed that distribute drugs locally or precisely to target sites, therefore achieving the appropriate blood levels. There is great promise for the future of biomimetic and bioinspired systems since they have the ability to overcome several challenges related to polymeric drug delivery. It will have successfully facilitated the integration of biocompatible and bio-related copolymers and dendrimers in cancer therapies, especially in their function as carriers for potent anti-cancer agents such as doxorubicin and cisplatin. Dendrimers are a potential new scaffold for polymeric drug delivery systems due to their special properties, which include their well-defined molecular weight, globular topology, high degree of branching, and multivalence. Future drug delivery systems may allow us to employ a wider range of polymer combinations owing to the design and synthesis of novel polymers [51].

CONCLUSION

Over the past few decades, advancements in polymer science have made easy to safely and efficiently deliver bioactive to target sites. Thus, the selection of suitable polymers plays a vital role in the creation of a delivery system. The ultimate goal is to create polymers that are biodegradable, biocompatible, affordable, and have multiple applications. The focus of polymer research will be on transforming the chemical and physical properties of polymers to create unique and imaginative copolymer combinations. These combinations will include bioresponsive and targeted components that can offer a variety of bioactive chemicals in future. Molecular imprinting supercritical fluid technology and nanoscale engineering are among of the most recent fabrication and production techniques that will undoubtedly transform the creation, application, and functionality of polymer-based DDSs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

RB-Conceptualization, reviewing and editing; PK, AG and DD-Writing and reviewing; SS and TS-Reviewing. All the authors are agreed for the publication of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

Kumar N, Pahuja S, Sharma R. Pharmaceutical polymers a review. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2019;9(1):27-33. doi: 10.25258/ijddt.9.1.5.

Bejenaru C, Radu A, Segneanu AE, Bita A, Ciocilteu MV, Mogoşanu GD. Pharmaceutical applications of biomass polymers: review of current research and perspectives. Polymers. 2024;16(9):1182. doi: 10.3390/polym16091182, PMID 38732651.

Pramanik S, Chakraborty P. Interpenetrating polymer network in drug delivery formulations: revisited. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12(6):5-11. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i6.33117.

Parameshwar K, Sahoo SK. A review of merely polymeric nanoparticles in recent drug delivery system. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(4):4-12. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i4.43239.

Nagam SP, Jyothi AN, Poojitha J, Aruna S, Nadendla RR. A comprehensive review on hydrogels. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2016;8(1):19-23.

Zorah M, Mudhafar M, Naser HA, Mustapa IR. The promises of the potential uses of polymer biomaterials in biomedical applications and their challenges. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(4):27-36. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i4.48119.

Pillai O, Panchagnula R. Polymers in drug delivery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5(4):447-51. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00227-1, PMID 11470609.

Bustos Terrones YA. A review of the strategic use of sodium alginate polymer in the immobilization of microorganisms for water recycling. Polymers. 2024;16(6):788. doi: 10.3390/polym16060788, PMID 38543393.

Konwarh R, Singh AP, Varadarajan V, Cho WC. Harnessing alginate based nanocomposites as nucleic acid/gene delivery platforms to address diverse biomedical issues: a progressive review. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications. 2024 Jun;7:100404. doi: 10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100404.

Duong T, Vivero Lopez M, Ardao I, Alvarez Lorenzo C, Forgacs A, Kalmar J. Alginate aerogels by spray gelation for enhanced pulmonary delivery and solubilization of beclomethasone dipropionate. Chem Eng J. 2024 Apr 1;485:149849. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.149849.

Sk Mosiur R, Dutta G, Biswas R, Sugumaran A, M Salem M, Gamal M. Succinyl curcumin conjugated chitosan polymer prodrug nanomicelles: a potential treatment for type-II diabetes in diabetic BALB/c mice. Acta Chim Slov. 2024;71(2):421-35. doi: 10.17344/acsi.2024.8658, PMID 38919100.

Parambil A, Maanvizhi S, Kuttalingam A, Chitra V. Spray-dried chitosan microspheres for sustained delivery of trifluoperazine hydrochloride: formulation and in vitro evaluation. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(3):200-7. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i3.47222.

Biswas R, Mondal S, Ansari MA, Sarkar T, Condiuc IP, Trifas G. Chitosan and its derivatives as nanocarriers for drug delivery. Molecules. 2025;30(6):1297. doi: 10.3390/molecules30061297, PMID 40142072.

Lucero MJ, Ferris C, Sanchez Gutierrez CA, Jimenez Castellanos MR, De Paz MV. Novel aqueous chitosan-based dispersions as efficient drug delivery systems for topical use. Rheological textural and release studies. Carbohydr Polym. 2016 Oct 20;151:692-9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.006, PMID 27474615.

Cheng C, Chen S, Su J, Zhu M, Zhou M, Chen T. Recent advances in carrageenan-based films for food packaging applications. Front Nutr. 2022 Sep 9;9:1004588. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1004588, PMID 36159449.

James S, Moawad M. Study on composite hydrogel mixture of calcium alginate/gelatin/kappa carrageenan for 3D bioprinting. Bioprinting. 2023;31:17:e00273. doi: 10.1016/j.bprint.2023.e00273.

Vlachopoulos A, Karlioti G, Balla E, Daniilidis V, Kalamas T, Stefanidou M. Poly(lactic acid) based microparticles for drug delivery applications: an overview of recent advances. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(2):359. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14020359, PMID 35214091.

Fattahi F, Zamani T. Synthesis of polylactic acid nanoparticles for the novel biomedical applications: a scientific perspective. Nanochem Res. 2020 Jan;5(1):1-13. doi: 10.22036/ncr.2020.01.001.

Nifantev IE, Tavtorkin AN, Shlyakhtin AV, Ivchenko PV. Chemical features of the synthesis degradation molding and performance of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) and PLGA-based articles. Eur Polym J. 2024 Jul 24;215:1-33. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2024.113250.

Little A, Ma S, Haddleton DM, Tan B, Sun Z, Wan C. Synthesis and characterization of high glycolic acid content poly(glycolic acid-co-butylene adipate-co-butylene terephthalate) and poly(glycolic acid-co-butylene succinate) copolymers with improved elasticity. ACS Omega. 2023;8(41):38658-67. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c05932, PMID 37867663.

Gentile P, Chiono V, Carmagnola I, Hatton PV. An overview of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) based biomaterials for bone tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(3):3640-59. doi: 10.3390/ijms15033640, PMID 24590126.

Lu G, Li B, Lin L, Li X, Ban J. Mechanical strength affecting the penetration in microneedles and PLGA nanoparticle assisted drug delivery: importance of preparation and formulation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 Apr;173:116339. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116339, PMID 38428314.

Loureiro JA, Pereira MC. PLGA based drug carrier and pharmaceutical applications: the most recent advances. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(9):903. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12090903, PMID 32971970.

Razavi MS, Abdollahi A, Malek Khatabi A, Ejarestaghi NM, Atashi A, Yousefi N. Recent advances in PLGA-based nanofibers as anticancer drug delivery systems. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023 Aug;85:1-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104587.

Rahman MS, Hasan MS, Nitai AS, Nam S, Karmakar AK, Ahsan MS. Recent developments of carboxymethyl cellulose. Polymers. 2021;13(8):1345. doi: 10.3390/polym13081345, PMID 33924089.

Capanema NS, Mansur AA, De Jesus AC, Carvalho SM, De Oliveira LC, Mansur HS. Superabsorbent crosslinked carboxymethyl cellulose-PEG hydrogels for potential wound dressing applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018 Jan;106:1218-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.124, PMID 28851645.

Yu S, Budtova T. Creating and exploring carboxymethyl cellulose aerogels as drug delivery devices. Carbohydr Polym. 2024 May 15;332:121925. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.121925, PMID 38431419.

Tundisi LL, Mostaco GB, Carricondo PC, Petri DF. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose: physicochemical properties and ocular drug delivery formulations. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021 Apr 1;159:105736. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2021.105736, PMID 33516807.

Zainal SH, Mohd NH, Suhaili N, Anuar FH, Lazim AM, Othaman R. Preparation of cellulose-based hydrogel: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;10:935-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.12.012.

Chen Y, Zhang L, Xu J, Xu S, LiY, Sun R. Development of a hydroxypropyl methylcellulose/polyacrylic acid interpolymer complex formulated buccal mucosa adhesive film to facilitate the delivery of insulin for diabetes treatment. Macromol. 2024 Jun 2;269:1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131876, PMID 38685543.

Murtaza G. Ethylcellulose microparticles: a review. Acta Pol Pharm. 2012;69(1):11-22. PMID 22574502.

Wildy M, Wei W, Xu K, Schossig J, Hu X, La Cruz DS. Exploring temperature-responsive drug delivery with biocompatible fatty acids as phase change materials in ethyl cellulose nanofibers. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;266(1):131187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131187, PMID 38552686.

Wasilewska K, Winnicka K. Ethylcellulose a pharmaceutical excipient with multidirectional application in drug dosage forms development. Materials (Basel). 2019;12(20):3386. doi: 10.3390/ma12203386, PMID 31627271.

Ingole SA, Kumbharkhane A. Temperature-dependent broadband dielectric relaxation study of aqueous polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K-15, K-30 and K-90) using a TDR. Phys Chem Liq. 2021;59(5):806-16. doi: 10.1080/00319104.2020.1836641.

Sammour OA, Hammad MA, Megrab NA, Zidan AS. Formulation and optimization of mouth dissolve tablets containing rofecoxib solid dispersion. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2006;7(2):E55. doi: 10.1208/pt070255, PMID 16796372.

Borji BK, Pourmadadi M, Tajiki A, Abdouss M, Rahdar A, Diez Pascual AM. Polyvinyl pyrrolidone/starch/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite: a promising approach for controlled release of doxorubicin in cancer therapy. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024;95:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105516.

Sandu MK, Majumdar S, Chatterjee S, Mazumder R. Optimization and characterization of xanthan gum-based multiparticulate formulation for colon targeting. Intelligent Pharmacy. 2024;2(3):339-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2024.02.007.

Signorini S, Delledonne A, Pescina S, Bianchera A, Sissa C, Vivero Lopez M. A sterilizable platform based on crosslinked xanthan gum for controlled release of polymeric micelles: ocular application for the delivery of neuroprotective compounds to the posterior eye segment. Int J Pharm. 2024 May 25;657:124141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124141, PMID 38677392.

Yagoub NA, Nur AO, Aleanizy FS, Osman Z. Evaluation of different grades of guar gum acacia gum and polyvinyl pyrrolidone as cross-linkers in producing submicron particles. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(6):136-43. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022v15i6.44923.

Zarbab A, Sajjad A, Rasul A, Jabeen F, Javaid Iqbal M. Synthesis and characterization of guar gum based biopolymeric hydrogels as carrier materials for controlled delivery of methotrexate to treat colon cancer. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2023;30(8):103731. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103731, PMID 37483836.

Roy C, Gandhi A, Manna S, Jana S. Fabrication and evaluation of carboxymethyl guar gum chitosan interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery. Med Nov Technol devices. 2024;22:2-7. doi: 10.1016/j.medntd.2024.100300.

Patra CN, Priya R, Swain S, Kumar Jena GK, Panigrahi KC, Ghose D. Pharmaceutical significance of eudragit: a review. Future J Pharm Sci. 2017;3(1):33-45. doi: 10.1016/j.fjps.2017.02.001.

Furuishi T, Kunimasu K, Fukushima K, Ogino T, Okamoto K, Yonemochi E. Formulation design and evaluation of a transdermal drug delivery system containing a novel eptazocine salt with the eudragit® E adhesive. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019 Dec;54:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101289.

Anwar MZ, Kathuria H, Chiu GN. Development of a eudragit-based hydrogel for the controlled release of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs for the treatment of wound infections. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024;94:1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105484.

Liu Z, Ye L, Xi J, Wang J, Feng Z. Cyclodextrin polymers: structure synthesis and use as drug carriers. Prog Polym Sci. 2021;118:1-24. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2021.101408.

Pinelli F, Ponti M, Delleani S, Pizzetti F, Vanoli V, Vangosa FB. β-Cyclodextrin functionalized agarose-based hydrogels for multiple controlled drug delivery of ibuprofen. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Dec 1;252:126284. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126284, PMID 37572821.

Mandal S, Khandalavala K, Pham R, Bruck P, Varghese M, Kochvar A. Cellulose acetate phthalate and antiretroviral nanoparticle fabrications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Polymers. 2017;9(9):423. doi: 10.3390/polym9090423, PMID 30450244.

Vidal Romero G, Rocha Perez V, Zambrano Zaragoza ML, Del Real A, Martinez Acevedo L, Galindo Perez MJ. Development and characterization of pH-dependent cellulose acetate phthalate nanofibers by electrospinning technique. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(12):3202. doi: 10.3390/nano11123202, PMID 34947551.

Hua D, Liu Z, Wang F, Gao B, Chen F, Zhang Q. pH responsive polyurethane (core) and cellulose acetate phthalate (shell) electrospun fibers for intravaginal drug delivery. Carbohydr Polym. 2016 Oct 20;151:1240-4. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.066, PMID 27474676.

Reshmi G, Mohan Kumar P, Malathi M. Preparation characterization and dielectric studies on carbonyl iron/cellulose acetate hydrogen phthalate core/shell nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. Int J Pharm. 2009;365(1-2):131-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.08.006, PMID 18775769.

Sung YK, Kim SW. Recent advances in polymeric drug delivery systems. Biomater Res. 2020;24:12. doi: 10.1186/s40824-020-00190-7, PMID 32537239.

Men X, Geng X, Zhang Z, Chen H, Du M, Chen Z. Biomimetic semiconducting polymer dots for highly specific NIR-II fluorescence imaging of glioma. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16:100383. doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100383, PMID 36017109.

Lee Y, Nam K, Kim YM, Yang K, Kim Y, Oh JW. Functional polymeric DNA nanostructure decorated cellulose nanocrystals for targeted and stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;340:122270. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122270, PMID 38858000.

Ullah A, Jang M, Khan H, Choi HJ, An S, Kim D. Microneedle array with a pH-responsive polymer coating and its application in smart drug delivery for wound healing. Sens Actuators B. 2021 Oct 15;345:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2021.130441.