Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 8, 8-24Review Article

MELATONIN: A FORGOTTEN MOLECULE TO PROTECT AGAINST SARS-COV-2 MEDIATED CARDIO-RESPIRATORY DISORDER

ABHIJIT GHOSH1, SUBHAMOY BANERJEE1, SHASHANKA DEBNATH2, ARNAB KUMAR GHOSH3*

1School of Biological Sciences and Technology, Department of Life Science-Microbiology, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, West Bengal-Main Campus, NH-12 (Old NH-34), Simhat, Haringhata, Nadia, West Bengal-741249, India. 2Department of Biotechnology and Bioinformatics-M. Tech Bioinformatics, University of Hyderabad, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, Telangana-500046, India. 3*School of Biological Sciences and Technology, Department of Applied Biology, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology-Main Campus, NH-12 (Old NH-34), Simhat, Haringhata, Nadia, West Bengal-741249, India

*Corresponding author: Arnab Kumar Ghosh; *Email: arnabkumar.ghosh@makautwb.ac.in

Received: 03 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 23 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

The worldwide pandemic of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains the worst disaster that modern times have experienced thus far. The dangerous virus has killed over a million individuals. The virulent virus destroys those individuals suffering from heart problems, along with their existing medical conditions. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) functions as the virus that causes COVID-19 and demonstrates fatal consequences on alveolar and cardiovascular performance, especially within hypertensive populations. Wild reactive oxygen species (ROS) develop throughout the process. The main role of the endogenous pineal gland-produced hormone melatonin is to regulate circadian rhythm patterns in all mammalian organisms and other vertebrate species. This molecule, with extensively reported antioxidant potential, is gradually decreasing in our bodies due to stress. Recent reports highlight its cardio-protective action in myocardial ischemia through receptor-dependent and also receptor-independent antioxidant mechanism(s). Furthermore, its effect on anti-inflammatory signaling pathways in cardiac diseases without any side effects intrigued us to consider it as a possible therapeutic agent against COVID-19-induced myocardial ischemia. This publication demonstrates, through molecular mechanisms, that melatonin functions as a promising therapeutic compound for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. The development of these melatonin-producing activities will generate additional physician availability to provide quality medical care to patients while upholding their health status.

Keywords: COVID-19, Melatonin, Myocardial ischemia, Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i8.54583 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

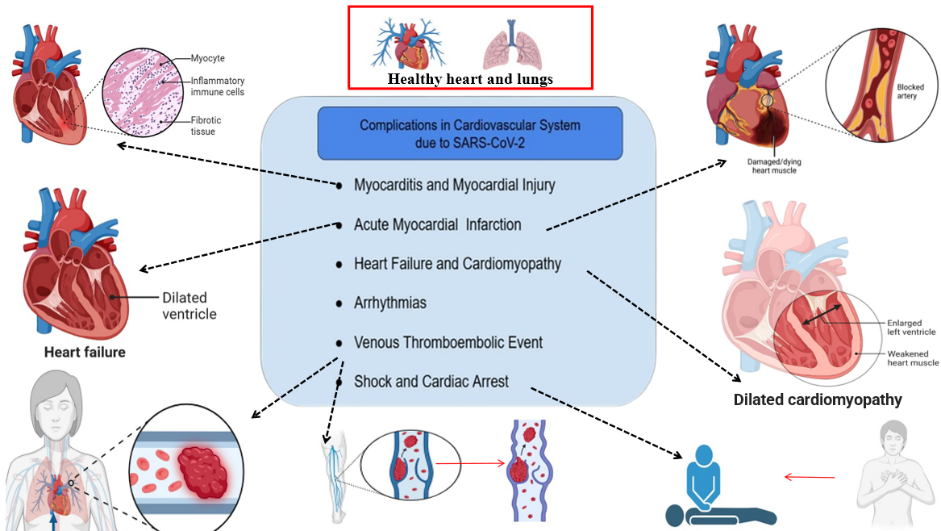

Millions of people have suffered severe impacts from numerous infectious disease outbreaks, which created massive public distress leading to vaccine development, while economists, scientists, and politicians faced substantial financial burdens. The disease appeared in late 2019 just as China approached its biggest yearly festival. The medical science community designated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as the official name when it confirmed the disease was caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). The global number of confirmed deaths and infected cases reached 48,539,872 in 215 different territories and countries worldwide in November 2020. History records COVID-19 as the deadliest event to date due to the large number of human fatalities from the coronavirus disease. The virus produces severe consequences for older individuals compared to younger ones in various population segments, which leads to higher death rates. The combination of COVID-19 infection with cardiovascular disease (CVD) causes patients to face an elevated mortality risk [1–6]. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) encompasses different acute myocardial ischemic (AMI) cases, which range from unstable angina to myocardial infarction. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 results in minor inflammation of major coronary vessels, together with non-occluding coronary diseases and whole-body inflammation. The administration of anti-COVID-19 medications leads to worsened ACS symptoms, while the virus results in deteriorated pre-existing ACS or triggers new type 2 myocardial infarction (T2MI) cases (fig. 1) [7]. Scientific evidence indicates that COVID-19 impacts microvascular properties through pericyte destruction and demonstrates heightened vulnerability in heart failure patients [8]. Patients receiving COVID-19 treatment must take immunosuppressive drugs, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and additional medications, but these medicines cause different heart-related side effects, such as myocardial ischemia (MI) events [9]. The pineal gland, located on the roof of the third ventricle in the brain, releases N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine, which is known as melatonin.

The evolutionary molecule known as melatonin exhibits crucial importance for conservation. The chemical compound melatonin exists throughout almost all organic entities, including vegetables and animals. The production of melatonin by mammals leads to multiple vital physiological impacts, including reproductive cycle control, immunity improvement, together with light signal transmission management and age-related changes [10]. Furthermore, melatonin plays a vital role through its antioxidant potential [11]. Scientific findings show that both melatonin and its metabolites guard cellular systems against reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as nitrogen-induced oxidative deterioration. The reactants will use one or more antioxidant mechanisms based on their specific properties [12, 13]. The ability of melatonin to stop apoptotic mitochondrial pathways emerges from its antioxidant properties, together with its possible influence on redox signals and ROS generation [14, 15]. Melatonin acts as a protective agent to stop hydroxyl radical (•OH) from damaging protein molecules, along with lipids and DNA, thereby preventing diverse health issues [16]. The protective mechanism of melatonin includes detoxification of cellular-damaging molecules, including superoxide anion radical (O2•-) [17], nitric oxide (NO•), peroxynitrite anion [18], hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [19], 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS+) cation radical [20], hemoglobin oxyferryl radical [21], and possibly the peroxyl radical (LOO•) [22, 23]. The compound also reduces the activities of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [24] while promoting multiple antioxidant enzymes [25]. The creation of free radicals occurs at lower rates, and electron leak prevention becomes more effective because of the protective role melatonin plays in the electron transport chain [26]. ROS exists as an essential diagnostic marker used for identifying various diseases, which include circulatory disruption and cardiovascular damage [12]. Various research has shown that ROS trapping during COVID-19 infection leads to myocardial ischemia by limiting blood flow to myocardial tissue below essential levels [17]. The cardiovascular protective capabilities of melatonin are currently being investigated because its therapeutic quantities appear without detrimental outcomes. The present review analyzes how melatonin might protect against illnesses affecting the heart and lungs caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

SARS-CoV-2 and cardiovascular complications

The newest virus entry route for SARS-CoV-2 occurs through ACE2 (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2) receptors existing in kidney tissue, along with intestinal tissue, cardiac cells, and pulmonary tissues [27, 28]. SARS-CoV-2 hijacks its receptor (ACE2) better during infection to block angiotensin II conversion into angiotensin III by the enzyme. The process also leads to the buildup of angiotensin II [20]. This can worsen the pulmonary and cardiovascular conditions that would otherwise be stable due to the anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrosis, anti-oxidation, and vasodilatory activities of ACE2 [29-31]. Several studies have suggested that complications in coagulopathy cause an immense risk for the development of venous and arterial thromboembolism in the case of coronavirus-infected patients [32]. SARS-CoV-2 uses Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors of endothelial cells to enter and trigger a substantial release of plasminogen activators [33]. Thereby, the elevated levels of fibrinogen and activated platelets result in the increased production of fibrin, resulting in a pro-coagulant shift. Unlike a healthy system, ACE2 is bound and occupied by SARS-CoV-2, which leads to the accumulation of angiotensin II and can also cause vasoconstriction, cellular damage, and clot formation [34]. During this, complications like coagulopathy and thrombosis readily occur. Myocardial attacks and pulmonary embolism can be a result of thrombosis. SARS-CoV-2-infected patients are generally observed to consist of an increased level of fibrinogen [35]. Furthermore, the high Interleukin-6 (IL-6) serum level present in the patient causes hepatic fibrinogen synthesis. Patients suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to COVID-19 require proper oxygen therapy that provides various advantages [36, 37]. Hence, there is an obstruction in proper cellular aerobic metabolism that can support the progression of cardiac arrhythmias due to disturbances in ionic currents and concentrations in the cell [38]. As a result, the patients probably acquire hypoxemia, which causes inflammation and injuries to the lung [3, 39, 40]. The respiratory tissues and vascular system receive damage after a minor attack has occurred (fig. 3). The occurrence of hypoxemia due to multiple pulmonary problems leads to this condition. High levels of ROS production, along with intracellular acidosis, damage cell membrane integrity through cardiomyocyte dependence on energy sources [41].

Fig. 1: Cardiovascular complications resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infections, which include medical issues arising from coronavirus infection, may result in arrhythmias, as well as venous thromboembolic events, heart failure, myocarditis, acute myocardial infarction, shock, and cardiac arrest

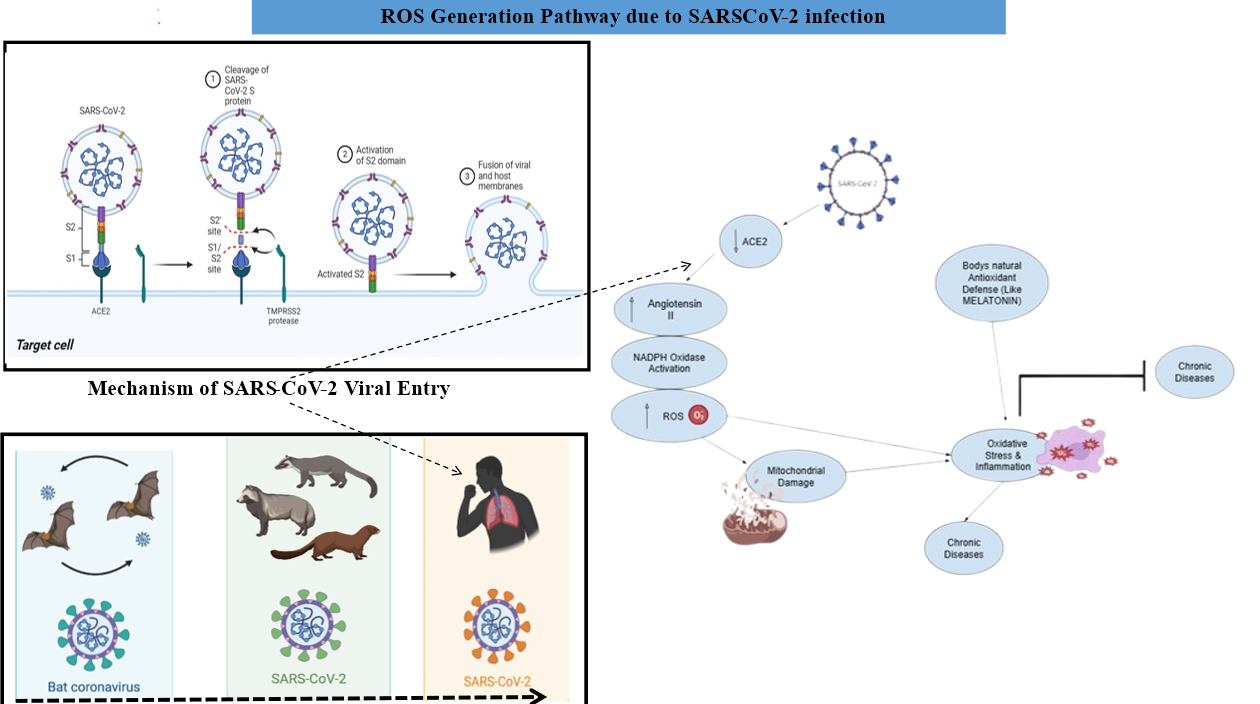

Generation of ROS upon infection of SARS-CoV-2

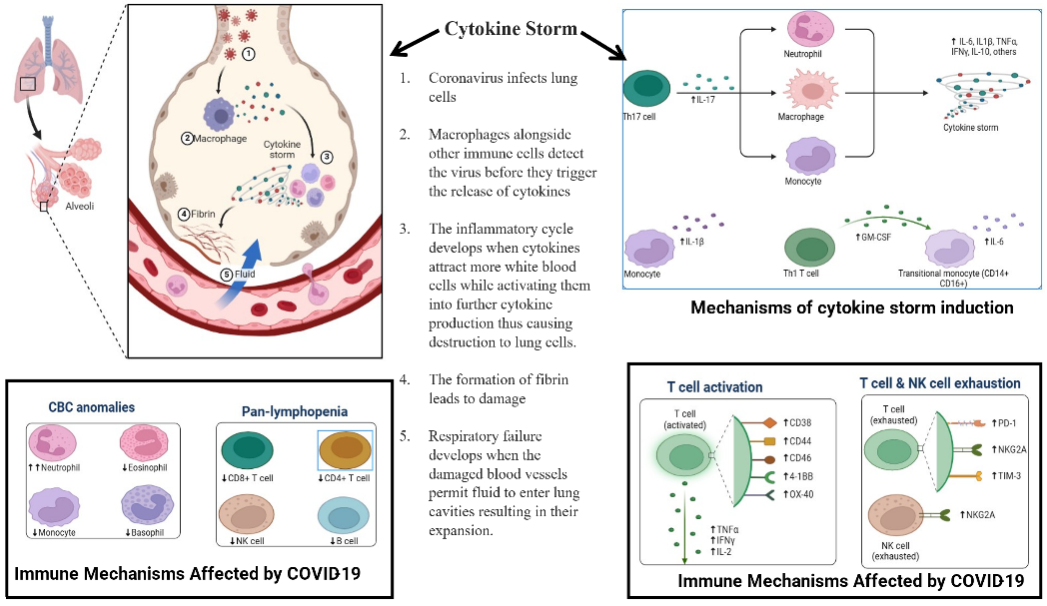

The unpaired electrons distinguish ROS, which include O2•-, NO•, •OH, and ONOO-, as simple molecules. Rational response pathways can be attributed to their strong binding capacity with cellular proteases that contain cysteine residues [42]. Uncontrolled reactive oxygen species production from SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers the host immune response process. Neutrophils, together with macrophages, produce excess reactive oxygen species after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cells create Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) through their activated state because of the oxidative burst to get rid of viral particles [43]. The virus spike protein alters the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) performance through receptor attachment to ACE2 [44]. The amount of angiotensin II rises. The main enzyme generating ROS functions through nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, whose activity rises following harmful disruptions to the body [45, 27]. Oxidative stress occurs when ROS accumulate, leading to cellular component damage, including proteins, DNA, and lipids, which worsens inflammatory activity. SARS-CoV-2 infects mitochondria, which induces dysfunction that worsens ROS production into a harmful feedback loop between oxidative damage and inflammation [47]. The development of COVID-19 symptoms becomes more severe primarily due to excessive ROS levels, particularly among patients who experience either cytokine storm or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Several research studies agree that intense ROS production leads to COVID-19 development, most notably when accompanied by severe symptoms involving cytokine storm and acute respiratory distress condition. Oxidative stress comes from different viral mechanisms that cause cell damage [48]. Further studies have corroborated that viral infections, including respiratory diseases, produce oxidative stress [49, 45]. When infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus activates innate immune response mechanisms by stimulating dendritic cells and macrophages through Toll-like and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) like receptors (NLRs), which prevents virus replication and minimizes harmful inflammatory responses of inflammatory cytokines and ROS [51]. The bodily entry of erythrocytes due to triggered ROS along with inflammatory processes that damage these cells and generate free iron together with heme (fig. 2). The spread activates both neutrophil cells and macrophage cells through this mechanism. Free radicals and hydrogen peroxide production through respiratory bursts create the oxidative stress that occurs in the body [52]. The plasma process of converting fibrinogen to abnormal fibrin clots becomes possible through both oxidative stress and free iron formation. The process creates micro-thrombosis that develops in both pulmonary microcirculation and the vascular system [53]. The cytokine storm (fig. 8) is produced due to the upregulation of cytokine expression through nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kβ). This causes the induction of oxidative stress through the activities of macrophage and neutrophil respiratory bursts, thereby causing damage to several tissues. Moreover, mitochondria also produce ROS that elevate the expression of iNOS through the NF-kβ pathway, and therefore NO• is produced. In addition, the virus inhibits nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which upregulates the expression of antioxidant enzyme-encoding genes, thus developing oxidative stress. ROS are mainly produced intracellularly as by-products in mitochondria during electron transport chain reactions, via various oxidoreductases, and by metal-catalyzed oxidation of metabolites. The electron-accepting ability to form superoxide anion radicals occurs because of decreased enzyme activity. The enzymes xanthine oxidase and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases, along with other electron transport chain enzymes, exhibit their activity in the presence of xanthine oxidase (XO) and NADPH oxidases. The dismutation process of O2•-creates H2O2. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) raises O2 non-enzymatically. Recent research indicates that a reaction rate increase of 104-fold will produce dismutation [54]. The reaction of H2O2 occurs rapidly when metals with elevated oxidation states combine. The combination of Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions leads to the production of superoxide anions and •OH (hydroxyl radical). The free radical OH ranks as the most potent radical that cells can produce [55]. The target cells containing type I and type II pneumocytes of alveoli experience lipid peroxidation, together with protein carbonylation and DNA damage, because general free radicals and specific •OH radicals attack all living cell contents at faster reaction rate constants. The effects of this reaction produce harmful situations that further cause serious alveolar disorders, triggering respiratory issues [56–58].

Fig. 2: The particular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to increased oxidative stress levels in patients. After infecting ACE2 proteins, the SARS-CoV-2 virus disables their ability to break down Ang II, thus activating O2•− production. Body cells generate additional O2•− radicals and •OH radicals through the NADPH oxidase pathway after SARS-CoV-2 infection, while concurrently producing existing radicals

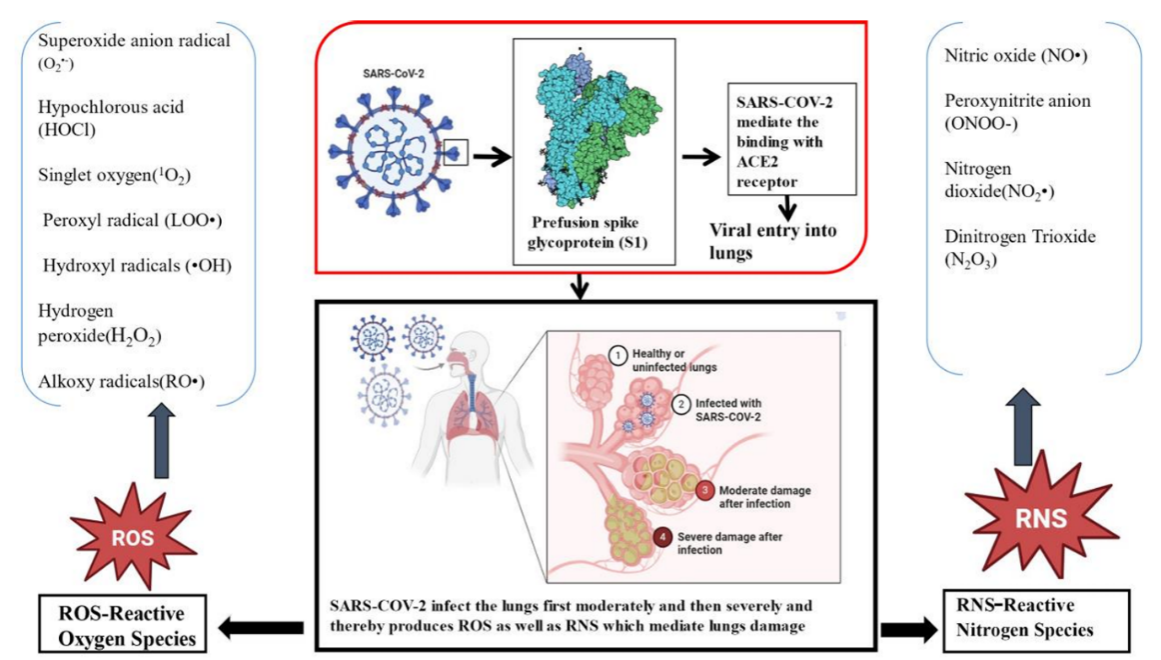

SARS-CoV-2 mediates myocardial ischemia and acute lung injury (ALI)

Medical studies demonstrate that SARS-CoV-2 causes more intense acute lung injury (ALI) symptoms and myocardial ischemic conditions than Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [59]. The lung receptors named angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) start their activation process after the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein attaches to them. The processes of blood vessel dilation and reduced inflammation occur due to these stimulations (fig. 3), while simultaneously increasing systemic oxidative stress (fig. 4) [60]. The virus can directly bind to ACE2 receptors, which facilitates endothelial tissue dysfunction [60]. Type II pneumocytes contain the highest expression of ACE2, and they secrete alveolar surfactant; moreover, they also supply stem cells for type I pneumocytes, which produce gas [61, 62]. A decrease in lung elasticity occurs through spike protein binding to ACE2, which impairs type II pneumocytes, resulting in less alveolar surfactant secretion. The damaged type I pneumocytes experience a reduced ability to repair gas exchange due to a decrease in their ability to regenerate [63]. Pathological differences in the pulmonary vasculature and lung alveoli occur due to alterations in gas exchange. COVID-19-affected lungs [64] are categorized by arteritis, vasodilation, and dysfunction of endothelial cells, which independently and jointly intensifies ventilation-perfusion incompatibility [33]. Autopsy studies of patients' lungs infected with COVID-19 demonstrate findings of diffuse alveolar damage, exemplified by extensive hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes, necrosis of epithelial tissue, fibrin deposition, and formation of the hyaline membrane [65–67]. The extent of CD4+helper T lymphocyte and CD8+cytotoxic T lymphocyte infiltration depends on the number of CD68+macrophages in the area [67, 68]. More inflammatory cytokines belonging to the TH1 group link to pathological changes within lung parenchymal cells by triggering interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-1β, in addition to IL-6. The majority of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients display limited severe symptoms from the excessive inflammatory reactions throughout their bodies and lungs. Multiple inflammatory markers increase in the blood, such as ferritin, D-Dimer, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, and macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α, as well as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [69]. SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to deadly outcomes through lung oxidative stress that manifests as increased reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and ROS levels [51]. Violent infections, along with transmission incidents, result in the production of oxidized substances. The production of excessive IL-6 in the alveoli by oxidized low-density lipoprotein functions as an inflammatory trigger in acute lung injury (ALI), according to research evidence [70].

Fig. 3: This schematic illustrates the progression of lung injury following a viral respiratory infection in a single integrated view. a. Moderate damage is characterized by inflammatory signaling, type II alveolar cell infection, fluid accumulation, reduced surfactant, and vasodilation, while the other displays severe damage marked by extensive protein-rich fluid buildup, neutrophilic infiltration, surfactant loss, cellular debris accumulation, and beginning scar tissue formation; the bottom section features succinct annotations explaining that while most patients develop moderate injury with limited compromise in gas exchange, a minority experience severe lung damage leading to critical respiratory failure. b. The spike proteins on the virus gain their initial cellular transformation series by carrying glycans that mucins in airways accommodate

Fig. 4: The infection moves from moderate to serious stages after the virus gains access through the ACE2 receptor, as illustrated on the left side with ROS such as the superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), hypochlorous acid (HOCl), and other radicals. Simultaneously, the right panel shows RNS featuring nitrogen oxide (NO•), peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), alongside NO₂• and N₂O₃. Through a united analysis, it becomes clear that unbalanced redox signaling produces both inflammatory and lung-damaging effects, which help explain COVID-19 disease mechanisms

Melatonin as a protective agent

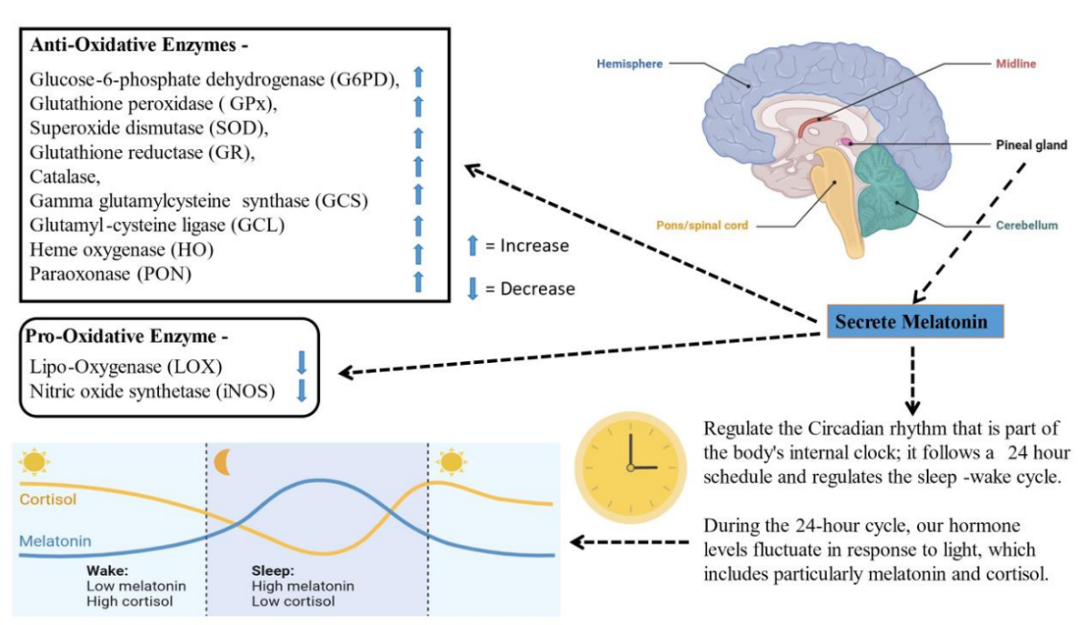

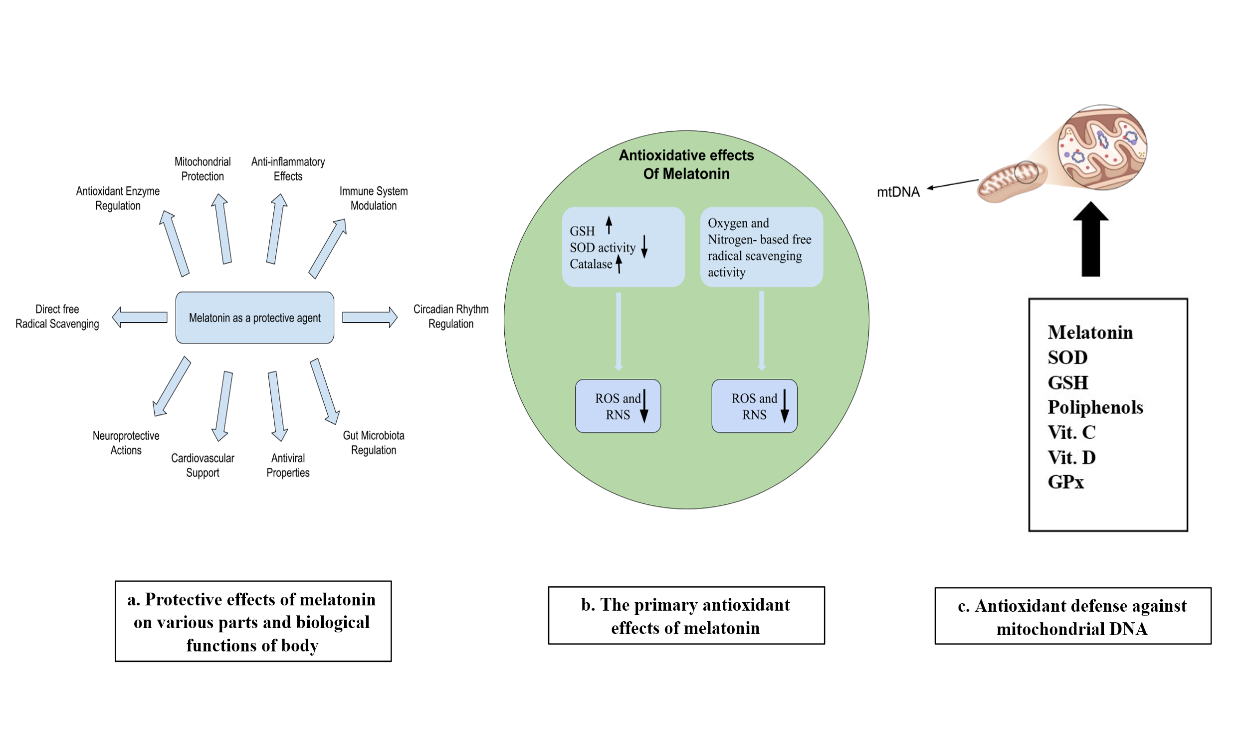

The research demonstrates that melatonin functions as an effective agent that scavenges oxygen-based and nitrogen-based reactive molecules, including ONOO– [71–77]. Scientific research indicates that melatonin demonstrates superior performance compared to other standard antioxidants in blocking free radical-mediated breakdown of certain molecules (fig. 5). Multiple in vivo studies demonstrate that melatonin exceeds natural antioxidants, including vitamin E, β-carotene, and vitamin C, as well as garlic oil [78–83]. The use of melatonin is proven to be superior to garlic oil, according to research findings [84]. The anti-inflammatory properties and antioxidant effects were previously demonstrated by research studies [85]. The effects of melatonin treatment on the lung health of premature infants who experience respiratory issues have been examined in scientific research [86, 87]. The strategy of using melatonin to control SARS-CoV-2-induced oxidation and inflammation remains strongly supported by research. Patients with COVID-19 benefit from this. The restoration of body glutathione (GSH) levels through melatonin consumption helps fight oxidative stress conditions in which GSH levels typically decrease. GSH suffers oxidation while the process creates glutathione disulfide (GSSG). The essential enzyme γ-glutamyl cysteine synthetase allows melatonin to activate glutathione reductase (GR) for the fast conversion of GSSG into GSH through disulfide bond reduction or hydrogenation [88].

Fig. 5: The body can regulate sleep-wake cycles through the creation of the melatonin hormone in the pineal gland and activate antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) simultaneously. The antioxidant properties of melatonin stem from its inhibitory effects on the enzymes LOX and iNOS, as well as its stimulatory effects on catalase, gamma-glutamylcysteine synthase (GCS), glutathione reductase (GR), heme oxygenase (HO), glutamylcysteine ligase (GCL), and paraoxonase (PON). A 24-hour integrated analysis of cortisol levels and daily melatonin produces vital insights into the hormonal processes that maintain anti-light defenses for the body's homeostatic oxidation mechanisms

Specific antioxidant enzymes with activities regulated by melatonin include cardiac tissue catalase and both entities of Cu-Zn-SOD, together with Mn-SOD within mitochondria

Medical science has established that melatonin provides therapeutic effects for many physiological conditions, including heart disease [12, 89]. Research analyzes the effects of melatonin pretreatment in reducing oxidative stress on rat cardiovascular tissues caused by isoproterenol bitartrate (ISO) [88]. The synthetic catecholamine ISO functions as a β-adrenergic receptor agonist when administered intraperitoneally in doses twice to rat cardiac tissues at 24 h intervals. The experimental animals died from ischemia exactly 24 h following their second drug administration [88, 90, 91]. ISO-treated animals likely show elevated activity of SOD (both cytosolic and mitochondrial), which results in oxidative stress in their cardiac tissues. High production of O2•-due to oxidative stress can deactivate the activities of these essential cardiovascular enzymes. However, the elevated expression of SODs is restored to the standard level upon pretreatment of the animals with melatonin [88]. Other researchers have confirmed these findings by studying streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat testicles [92]. Research indicates that melatonin affects the catalase activity levels in rats that receive ISO treatment. Studies indicate that ISO-induced cardiac tissues in rats show a substantial decrease in catalase activity compared to the measured SOD activity [93, 94]. Additional production of ROS creates an inhibition of enzymes that supposedly trigger this reaction. The rats pretreated with melatonin show regular catalase levels despite receiving ISO treatment [88]. These results are subsequently confirmed by another group of scientists in streptozotocin-induced diabetic testes [92, 95]. Multiple research studies provide evidence supporting the protective effect of melatonin as an antioxidant mechanism, which restores organ antioxidant enzyme activity to nearly normal levels.

Fig. 6: a. The various therapeutic characteristics of melatonin allow it to stabilize antioxidant enzymes and preserve mitochondrial structure and maintains anti-inflammatory balance for immune rhythm regulation and gut microbiome management as well as viral protection and heart health and brain defense while increasing antioxidant strength. b. Melatonin's main antioxidant properties enable it to produce GSH and catalase and activate SOD, which results in decreased oxidative and nitrosative particles. c. Melatonin and Super Oxide Dismutase SOD together with Glutathione GSH as well as vitamins C and D and Glutathione Peroxidase GPx protect mitochondrial DNA by working in mitochondrial processes against oxidative damage

The biochemical impact of melatonin on two stress indicators that are on the cardiac tissue lipid peroxidation (LPO) and reduced glutathione level (GSH)

Research indicates that melatonin shields against oxidative stress by adjusting different biomarkers in the body. Available research demonstrates that the administration of ISO to rats brings about oxidative stress conditions [88]. Two essential biomarkers, namely lipid peroxidation (LPO) and GSH reduction, appear abnormal when detecting cardiac tissue biomarkers [96-98]. The study demonstrates that administering ISO to rats leads to higher levels of lipid peroxidation (LPO) in their heart tissue. Scientific studies show that melatonin pretreatment of rats before ISO drug exposure helps avoid increases in LPO levels in their heart tissue. This experimental outcome is confirmed through multiple research studies. The research includes two groups of rats that received radiation treatment and a diabetes diagnosis. Similarly, the reduced glutathione content is observed to increase in the case of ISO induction in the cardiac tissue of rats [99-100]. Nevertheless, pretreatment with melatonin is beneficial for restoring the reduced glutathione content in them [88].

The impact of melatonin on the production of hydroxyl radicles in cardiac tissue and pro-oxidant enzymes such as xanthin oxidase

Xanthine oxidase significantly affects the production of ROS [101]. The effects of melatonin on O2 synthesis and pro-oxidant enzymes like xanthine oxidase (XO) and xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) were examined in the research. The study revealed that •O2 developed in the heart tissues of rats, thereby creating the final product •OH [88]. Their study clearly evidenced the increased levels of both XO and XDH in ISO-induced heart tissue compared to normal tissue. The measurements show a significant increase in superoxide anion radical production as a result. Pre-treating rats with melatonin helps maintain normal levels of the two pro-oxidant enzymes. Scientific research shows that rats treated with melatonin generate regular •OH amounts, but this value increases several times when their heart tissue undergoes ISO exposure [88]. This is highly significant of melatonin’s efficacy in neutralizing free radicals and is also evident in several other reports [102, 103].

Melatonin effects on the viability of cardiac mitochondria

Researchers have extensively studied how melatonin affects the survival of cardiac mitochondria [104]. Melatonin demonstrates stronger protective molecular properties that exceed the visible damage done to mitochondria from oxidative stress. The examinations confirmed the existence of living mitochondria in goat hearts through Janus Green B staining performed on cardiac mitochondrial tissues following the use of ISO and melatonin (fig. 7). The supravital mitochondrial stain of Janus Green B occurs because oxygen exists within the tissue. Several scientific investigations have proven that oxygen affects Janus Green B, turning it blue. The compound turns into a pale pink shade or becomes colorless when either ischemia or conditions without oxygen occur [105]. Observations under a fluorescent microscope demonstrate that damaged tissues lack green fluorescence, while intact tissues still show green fluorescence after Janus Green B staining. The goat heart mitochondrial structure stands at a much lower integrity level than typical mitochondrial tissues because of ISO management. The application of melatonin to cardiac mitochondria prevents tissue deterioration. Research clearly demonstrates how melatonin acts as protection against oxidative stress generated by cardiac mitochondria [104].

Fig. 7: Graphical representation of changes in fluorescence intensity of janus green B-stained mitochondrial sections. Numerical values above error bars indicate coefficients of variation. #P<0.001 versus Control; p<0.001 vs ISO µM [107]

Effect of melatonin on electron transport chain (ETC) and Kreb’s cycle enzyme in cardiac tissue

Scientists conclude that mitochondria both produce energy within cells and represent the main site where oxidative stress occurs [107]. The biochemical sequences within mitochondria, which science has confirmed exist are Kreb's cycle and the electron transport chain (ETC). Oxidative phosphorylation represents the cellular process through which mitochondria produce most cellular energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate. The production of ATP depends on electron transporting complexes (NADH-cytochrome C oxidoreductase and cytochrome C oxidase) together with protein complexes (ATP-synthase complex and ETC complexes I through IV) and oxidation-reduction series as well as molecular oxygen that reduces to produce water. The damaging effects of mitochondrial ROS occur through their reaction with protein thiols and iron-sulfur clusters to block the normal activity of ETC complexes [108–110]. Moreover, inhibition of enzymes associated with Kreb’s cycle enhances free radical formation [111]. During COVID-19 infection elevated oxidative stress altered the function of Kreb's cycle and ETC-associated enzymes in heart tissue, which caused free electrons to leak and resulted in higher ROS production levels [112]. Rats receiving ISO show decreased activity levels in both the PDH complex and other respiratory enzymes of the Krebs cycle. The activity level of every enzyme within the rats' bodies diminishes after they receive an ISO injection [113]. Rats who received melatonin treatment before the experiment showed higher activity levels of enzymes. The previous study showed that rats receiving ISO had decreased ETC activity levels. The enzymes Cytochrome C oxidase and NADH-Cytochrome C Oxidoreductase. The decreased activity of these enzymes proves that mitochondrial oxidative stress has elevated to harmful levels. The activity of enzymes restores to normal levels in rats who receive melatonin before analysis [113]. The research demonstrates how melatonin's strong redox potential enables it to join or leave electron flows between the complexes because of its beneficial characteristics [15]. This ability of melatonin to provide protection to the mitochondrial functions is also validated by other group of scientists [114].

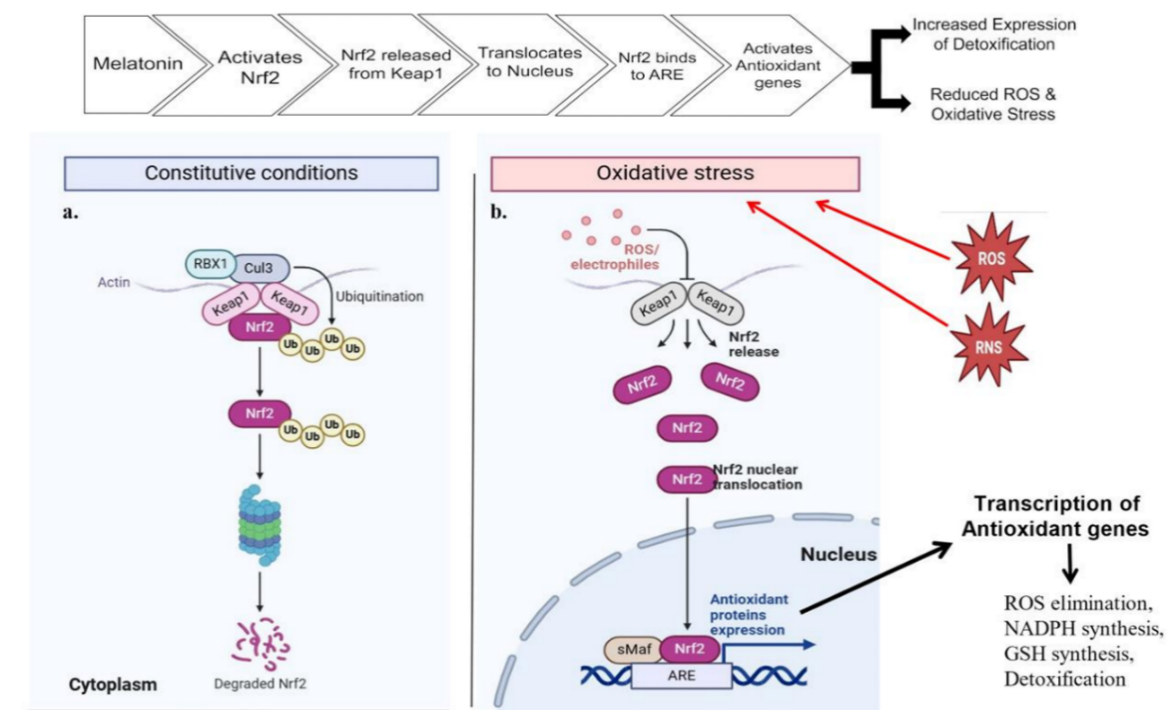

The antioxidant properties of melatonin activate nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)

Scientists evaluated the immunotoxicity activated through the enhanced capacity of melatonin to interact with aluminium chloride (AlCl3) [115]. The research reveals the process by which melatonin activates the nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway to reduce AlCl3-induced splenic oxidative stress by lowering ROS production and elevating SOD activity levels. The activity of Nrf2 toward melanin speeds up through the nuclear translocation of Nrf2. The research demonstrates that melatonin protects testicular cells against oxidative stress and apoptosis triggered by stress [116]. The study indicates that melatonin works as an iNOS regulator while promoting SOD and reduced glutathione (GSH) levels and reducing ROS levels and tumor necrosis factor alpha [117]. The research demonstrates how Nrf2/HO-1 signaling becomes activated during laboratory experiments. The research demonstrates that melatonin produces antioxidant effects on pancreatic acinar cells obtained from mice [114]. The activation process of Nrf2 signaling by melatonin happens through the protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca²⁺ signaling pathways, which leads to less oxidative stress production in these cells [118]. The research established that melatonin provides defense against manganese (Mn)-induced oxidative damage. Multiple brain disorders, such as those affecting motor functions and neuronal cells, and apoptosis, together with ROS production, develop because of Mn exposure and GSH decreases. Exposure to Mn becomes less harmful to cells when treated with melatonin because this hormone triggers Keap1 inhibition and activates the Nrf2/ARE signaling cascade (fig. 10).

Melatonin and its anti-inflammatory effects

Through antioxidative mechanisms, melatonin enhances SOD enzyme activity while suppressing the production of the enzyme nitric oxide synthase [119]. It can also interact with the generated free radicals directly, thus operating as a free radical scavenger [120]. The main indication of inflammation is elevated concentrations of cytokines and chemokines. Treatment with melatonin leads to both new production and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-8 (IL-8). Higher therapeutic melatonin levels lead the body to generate enhanced anti-inflammatory cytokines, with interleukin-10 (IL-10) being among the most important [121, 122]. Multiple studies explore how melatonin exerts its anti-inflammatory effects. The mechanism by which melatonin reduces inflammation involves SIRT1 activation, which decreases the activation of the protein HMGB1 to limit macrophage transformation into pro-inflammatory cells [123]. Activation of NF-κB is often accompanied by pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative responses in cases of ALI. Meanwhile, melatonin causes a reduction in activated NF-κB through its anti-inflammatory activities in T lymphocytes (T-cells) and lung tissue [124-126]. Nrf2, being an important factor, is induced by melatonin, showing therapeutic effects in cardiovascular diseases [127]. In COVID-19 ALI, Nrf2 activation becomes essential due to melatonin because of its anti-inflammatory properties. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 show signs of an inflammatory cytokine storm during COVID-19 infection [41, 128–130]. The pathological definition of COVID-19 as a diagnosis stands as the most accepted theory in medical research. When inflammatory cytokines activate in regions of inflammation, they send signals to immune cells, which stimulate a response while free radicals form alongside vascular leakage. According to research findings, COVID-19 patients demonstrate enhanced levels of interferon γ (IFN-γ), IL-1β, and the two distinct proteins monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) in their bloodstream. A greater amount of IL-4 and IL-10 appears during these conditions according to body production. The anti-inflammatory effect of melatonin becomes powerful through the prevention of the cytokine storm and inflammatory cell recruitment.

Fig. 8: This illustration shows that neutrophils, monocytes, and TH17 cells, along with transitional monocytes, lead to a cytokine storm, while neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils experience changes in pan-lymphopenia, including CD4 and CD8 T cells, as well as B cells. Another part of the schematic illustrates the relationship between CD38 and T cell activation and NK cell exhaustion, as well as alterations in the expression of CD44, CD69, 4-1BB, OX-40, PD-1, NKG2A, and TIM-3. The development of integrative treatment strategies benefits from human immune responses that create pathophysiological patterns in COVID-19 infections.

Anti-inflammatory action of melatonin by inhibiting TLR4 pathway

Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor/Resistance protein (TIR)-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) triggers TLR4 activation, which leads to the activation of NF-κB and the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3). The activation pathway of NF-κB drives the expression levels of NLRP3 molecules upward. The inflammatory response becomes more intense through NLRP3 activation because the process leads to proinflammatory cytokine production and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis. The protein complex NF-κB activates cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). Microglia and phagocytes become active through the combined substances Aβ, COX-2, and NO. Neural and inducible forms of NO synthase (nNOS and iNOS) generate NO molecules, and Aβ is synthesized by β and γ-secretase enzymes. Phagocytes, along with microglia, activate myeloperoxidase (MPx) and NADPH oxidase (Nox2) after activation [127]. The process forms free oxygen radicals as its end-product. ETC leaks of reactive nitrogen species cause the formation of ROS particles. Under hypoxic conditions, ROS formation occurs as a natural result. Enhanced ROS levels enable thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) to activate and consequently initiate the cascade of Nox4, NF-κB, and NLRP3 activity. When Nox4 gets activated, it leads to greater production of ROS. Melatonin proves its ability to minimize inflammation by reducing the expression levels of β-APP, TRIF, TLR4, NF-κB, iNOS, nNOS, and β and γ-secretase. The suppression of both phagocyte and microglia activation is achieved by melatonin through direct or indirect mechanisms that prevent free oxygen radical formation. By increasing Nrf2 levels, melatonin contributes to lowering ROS amounts [132–175].

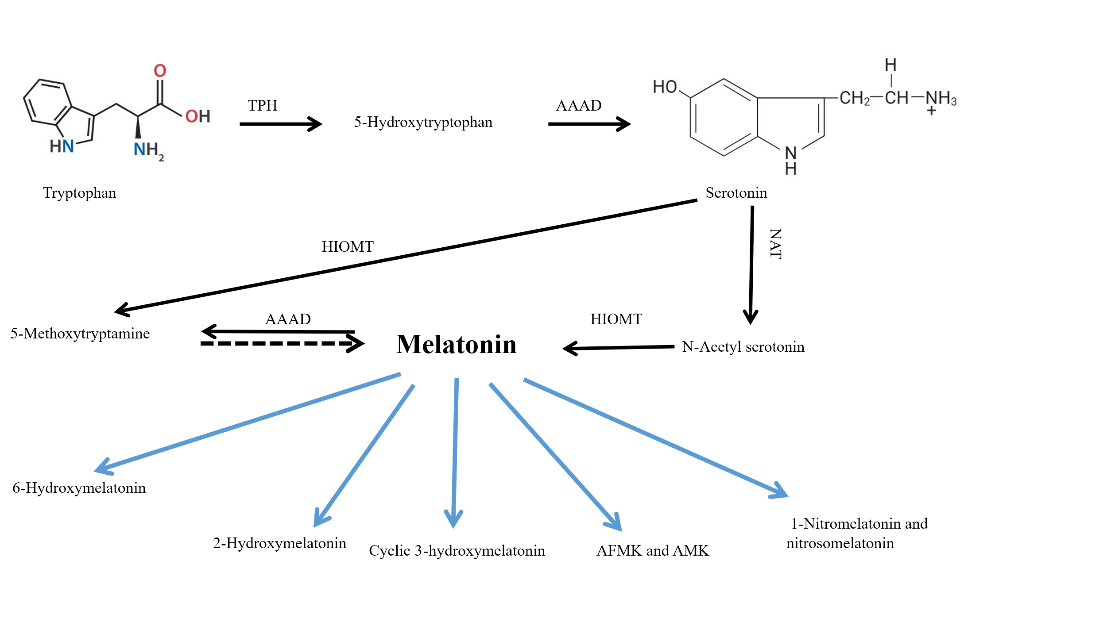

The ‘never-ending’ cascade of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action of melatonin and its metabolites

Multiple studies prove that melatonin possesses strong survival characteristics across different living organisms. Photosynthetic prokaryotes have synthesized melatonin since the first day of their existence. Free melatonin functions as an independent, receptor-free protector against various radicals in the body. During early evolutionary times, the main role of melatonin was to eliminate radicals [176]. Researchers analyze the biochemical transformations and functions of the derivative products of melatonin since it acquired its receptor-responsive characteristics. Research indicates that 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate functions as the main urinary excretion product of melatonin, followed by its subsequent metabolite N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK) [177]. Several identification pathways for AFMK production have been confirmed based on both laboratory tests and animal models. Materials that generate ROS and RNS react with melatonin, while enzymatic and pseudo-enzymatic mechanisms, as well as ultraviolet radiation, contribute to its metabolism. AFMK stands as the only melatonin metabolic product that scientists observe in unicellular life, as well as in metazoans, humans, and other mammals. Organisms with low evolutionary standing lack the detection of hydroxy-melatonin sulfate. Studies indicate that AFMK functions as a melatonin derivative that predates the development of 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate because one molecule of melatonin has been shown to provide protection from ROS/RNS using the AFMK pathway [176]. Studies show that among its diverse metabolites, which include secondary, tertiary, and quaternary variants, melatonin possesses free radical scavenging properties. The extended series of chemical reactions between melatonin and ROS/RNS occurs due to multiple metabolites that sustain the free radical scavenging mechanism. The cascade reaction distinguishes melatonin as an antioxidant substance, even though other antioxidant substances exist. The cascade reaction creates highly effective free radical protection, which makes melatonin efficient even at small dosages. The protective role of melatonin explains why this compound exists in notable amounts within tissues and organs. Certain types of stressors, such as physical exercise in humans and feeding restriction in rats, lead to elevated synthesis of melatonin in the body. Severely stressed individuals experience rapid decreases in melatonin due to its quick use. The quick consumption rate of melatonin occurs after stress-induced ROS/RNS contact, rather than reductions in its production, because these agents actively break down circulating melatonin. An organism protects itself from oxidative stress by rapidly consuming its first line of antioxidant protection molecules, called melatonin, during times of heightened stress. The metabolism of melatonin changes according to the oxidative level of an organism. Research indicates that higher oxidative conditions in the body lead to increased production of the AFMK ratio and cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin [176]. The two melatonin metabolite markers serve as indicators to measure oxidative stress levels in organisms. Together with AFMK, the hydroxylated metabolite 2-hydroxymelatonin also plays this role. Scientists have limited knowledge about the enzymes that break down 2-hydroxymelatonin within living organisms. The research shows that melatonin interacts with ROS/RNS, resulting in the formation of 2-hydroxymelatonin. Through in vitro analysis, it is established that 2-hydroxymelatonin serves as the principal product from the reaction of hypochlorous acid with melatonin. Published data present AFMK as a remarkable substance with significant potential to affect melatonin metabolism [178]. Research on AFMK as a brain metabolite of melatonin began thirty years ago with Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase was recognized by scientists as the sole catalytic enzyme at that time. Before recent times, it was possible to synthesize AFMK. The combination of melatonin with H2O2 creates a nonenzymatic reaction that produces AFMK [176]. Research indicated that AFMK develops from enzymatic processes, along with pseudo-enzymatic, UV irradiation, and ROS processes. The synthetic laboratory atmosphere produces two other negligible melatonin metabolites called 1-nitromelatonin and 1-nitrosomelatonin (fig. 9). On its own, melatonin enables the production of ONOO through interaction with the nitrogen dioxide radical and NO• [179–181]. Available research does not contain information about the formation of 1-nitromelatonin and 1-nitrosomelatonin within living organisms.

Fig. 9: Melatonin and its metabolites production, which reduces the ROS/RNS level and thereby reduces the ROS-mediated cellular damages

The molecular targets responsible for the anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin

G-protein-coupled receptors contain MT1 as one subtype of the melatonin receptor [182]. Upon binding to melatonin, MT1 gets activated, resulting in the activation of several downstream signaling cascades. As a result, Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK1/2), and the protein kinase B/Forkhead box O (Akt/FOXO1) complex are also activated and stimulate the activation of SIRT1. The active histone/protein deacetylase SIRT1 blocks NF-κB while activating Nrf2 when it becomes activated [183–190]. The activation of Sirtuin-1(SIRT1) leads to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (Pgc-1α) deacetylation. Activity is initiated in the transcriptional coactivator Pgc-1α upon deacetylation [191]. Pgc-1α regulates Nrf2 and is therefore responsible for its activation [192, 193]. Nrf2 remains inactive under normal physiological conditions by binding to its negative regulator, kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1(Keap1). Nrf2 breaks away from Keap1 (fig. 10) to become active through phosphorylation; then it travels to the nucleus to pair with MAF. Nrf2 generates dimers with macrophage activating factor (MAF), which allows the protein complex to activate the main antioxidant promoters, such as the genes for heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H: quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [184]. The activation of NLRP3 together with NF-κB serves to reduce inflammation when ROS are eliminated. The compound melatonin demonstrates its ability to minimize the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which include TNFα. The presence of melatonin obstructs the movement of interleukins combined with NF-κB, along with inflammatory mediators, including COX-2 and iNOS [88, 185]. Scientific research shows that melatonin enables the activation of Akt signaling to produce eNOS phosphorylation at Ser 1177. The reduction of NO levels, combined with symptom relief of pulmonary hypertension, occurs from these effects [186]. The pathway of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/Nrf2 signaling activates along with melatonin to boost GSH cellular levels [187].

Fig. 10: Through the activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway, melatonin establishes protective measures against oxidative stress in different organs, specifically the lungs, in the body. a. Melatonin enables the inactive Nrf2 molecule to detach from Keap1 proteins and maintain activity in the cytoplasm following exposure to oxidative damage. b. The binding separation of Nrf2 and Keap1 takes place as ROS and RNS levels increase. Melatonin releases Nrf2 from its inhibited state and then facilitates its nuclear movement until it reaches sMafs to activate genes through ARE sites. The protective effect of oxidative damage extends throughout the body because of melatonin's capability to reduce ROS while stimulating NADPH and glutathione synthesis

Melatonin work as an adjuvant for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2

One study indicates that melatonin treatment reduces inflammation markers, along with cytokines and gene expressions such as STAT4, STAT6, T-box, GATA-binding protein 3, ASC, and caspase-1 [188]. Recovery time shortens alongside the improvement of different clinical signs and symptoms when using this therapy. Melatonin is effective in reducing patient death rates and decreasing the occurrence of sepsis, as well as thrombosis, when used in severe conditions. The body produces the endocrine chemical melatonin in the mitochondria. The infection emerges from the pineal gland before reaching every part of the body. The medical community recognizes this substance as a potential therapy enhancer for COVID-19; it shows a strong anti-inflammatory response, antioxidant effect, and immune modulation properties. The evaluation analyzed participants who were 18 y of age or older during their COVID-19 diagnosis through CT monitoring and nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR testing. Many studies investigated whether melatonin therapy offers superior benefits compared to standard adult COVID-19 care for patients aged 18 y and older. Clinical and cohort research papers regarding how melatonin was conducted were included. Additional research based on COVID-19 care for conventional medical treatment patients aged 18 and above was conducted using four databases: Cochrane Library, Web of Science, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Scopus. The Cochrane risk of bias tool served as a means to evaluate clinical trials, while the cohort studies implemented the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for bias evaluation. The study group found a poor-quality status because bias risks were unclear or significant in two or more evaluation areas; fair-quality status occurred when one area contained a significant risk, while good-quality status meant that the evaluation areas had no bias according to the assessment findings. The research examined patients who had rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer, mild to moderate COVID-19, and melatonin allergies. The prescribed medication amount provided by researcher’s spans from 9 mg to 6 mg, and patients receive the oral treatment once per day for 10 d during the 14 d study duration. The research design featured the chronological grouping of participants by age groups, comorbidities, COVID-19 severity levels, and intervention durations, as well as case-control participants, control group members, and lengths of melatonin administration. Results show that melatonin reduces oxidant agents, including lipid peroxidation (LPO) and nitric oxide, as well as malondialdehyde, yet strengthens antioxidant agents, especially superoxide dismutase (SOD) and nitrite. D-dimers and intravascular clotting occur more frequently in severe COVID-19 patients because of elevated inflammatory mediators from endotheliitis and increased neutrophil production of NETs. Studies have discovered that when neutrophils interact less with endothelial cells, it causes reductions in vascular permeability. The use of melatonin administration proves effective in reducing the development of sepsis and thrombosis, thus leading to decreased mortality compared to the control patient group [189].

Effect of melatonin on oxygen saturation

The concept of the administration of melatonin in patients may indicate enhanced blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) and superior sleep quality [198]. Melatonin increases antioxidant defense by stimulating several gaseous transmitters, specifically nitric oxide, hydrogen sulfide, and others. Furthermore, gas transmitters facilitate the development of the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen (AHO) via multiple pathways: the production of diverse hemoglobin derivatives (including met-hemoglobin, nitrosohemoglobin, sulfohemoglobin, and others), the modulation of intra-erythrocytic dynamics that influence oxygen-binding affinity, and systemic effects on oxygen transport and delivery [190]. This modulation can enhance the sustained activation of the antioxidant system, thereby counteracting oxidative stress and preserving redox homeostasis. Melatonin has also been reported to induce a more pronounced rightward shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve during physical activity, thereby enhancing oxygen delivery and utilization in cellular tissues. The observed elevation in gas transmitters (nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide) following melatonin administration is significant for the development of the oxygen transport capacity of blood and the maintenance of the prooxidant-antioxidant equilibrium in the context of pulmonary embolism [191]. Therefore, it may be concluded that melatonin may serve as a beneficial therapeutic for both healthy individuals and COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, the notable improvement in blood oxygen saturation in the melatonin group relative to the controls may be attributed to melatonin's effect on oxygen transport and its utilization in tissues, a function that has been examined both experimentally and clinically [192-194].

Effect of melatonin on heart function during mitochondrial ischemia

The studies on the protective actions of melatonin that control heart functions during myocardial ischemia are clearly cited by the researchers (table 1) [88]. The authors examined how melatonin affects both blood pressure measurements and fluctuations in cardiac output. After receiving ISO, the rats experienced substantial decreases in their heart rates, along with their systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings. The administration of melatonin to rats prior to ISO treatment leads to substantial modifications in these parameters, but these changes are subsequently reduced. According to research, melatonin preserves systolic blood pressure in ISO-treated animals by maintaining its original state [195]. Thus, it is evident that melatonin restores cardiac output and blood pressure levels to provide sufficient O2 to the ischemic tissues.

Table 1: Melatonin-treated hearts reacted to isoproterenol (ISO) compared to untreated control hearts simultaneously

| Experiment parameter | Control | ISO | ISO+Melatonin | Reference |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 341±7.0 | 346±1.0 | 388±2.0 | [88] |

| Pₘₐₓ (mmHg) | 109±2.0 | 76±3.0 | 133±7.0 | |

| Pₘᵢₙ (mmHg) | 21.3±2.0 | 18.4±0.3 | 9.0±0.5 | |

| CO (μl/min) | 22494±1070 | 10837±342* | 15442±403 | |

| dP/dtₘₐₓ (mmHg/s) | 5280±489 | 2021±73* | 4960±352# | |

| dP/dtₘᵢₙ (mmHg/s) | -5308±309 | -1577±81* | -4943±151# |

[*P<0.01versus control, #P<0.01versus ISO.]

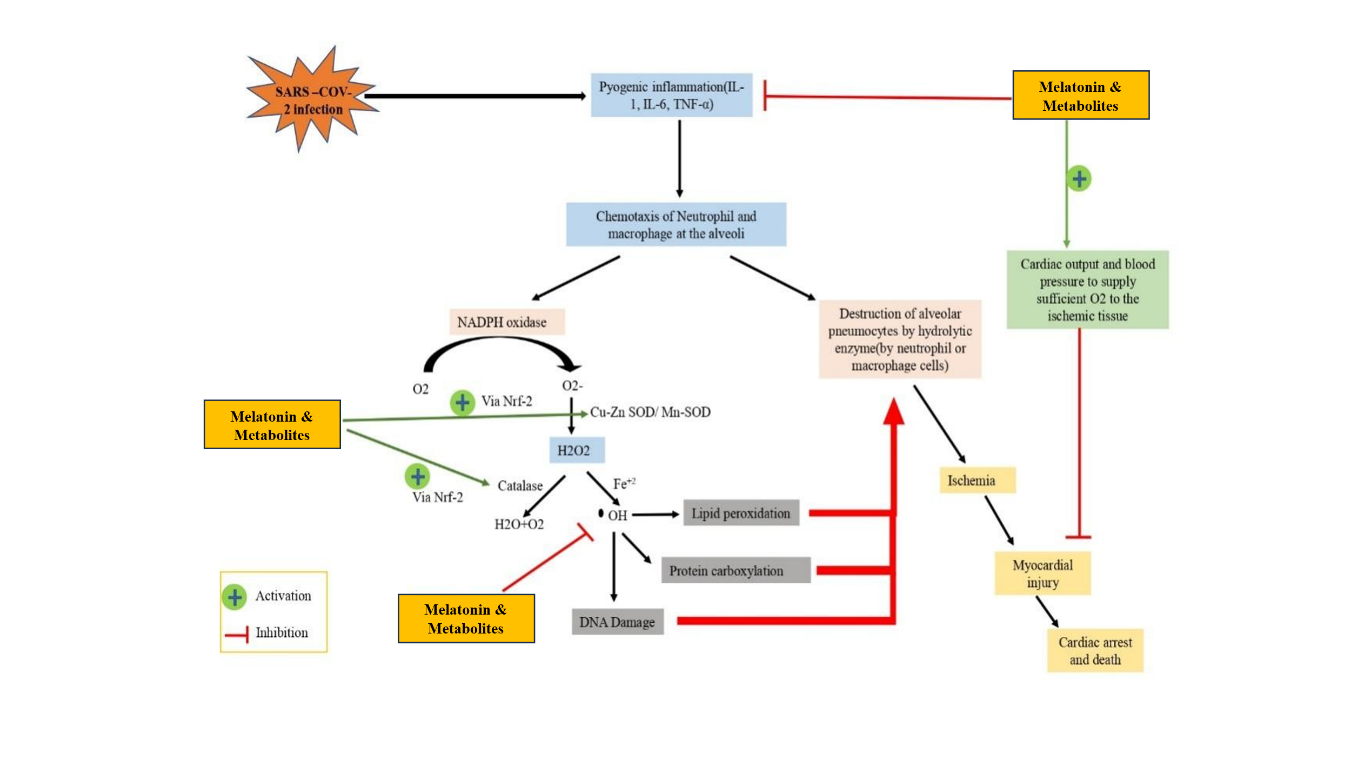

Fig. 11: The viral infection triggers proinflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α release by alveolar neutrophils and macrophages to create a state of pyogenic inflammation between them. The production of oxygen-superoxide depends on NADPH oxidase with Cu-Zn SOD while Mn-SOD converts the product into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Under normal conditions, Catalase converts H2O2 into oxygen and water molecules yet Fe2⁺ presence leads to H2O2 conversion into reactive hydroxyl radicals that initiate damaging lipid oxidation and harm DNA, together with proteins. Heart protection by melatonin occurs through an Nrf2 activation mechanism that reduces toxic reactive species production and through blood pressure and cardiac output elevation that provides needed oxygen supply to ischemic tissue to prevent myocardial damage and cardiac arrest leading to death.

DISCUSSION

Melatonin may not prevent the entry of the virus into the human body, but it has antioxidant properties and anti-inflammatory actions that safeguard both cardiac tissue and alveoli from damage induced by SARS-CoV-2 infections. Research indicates that melatonin manages circadian rhythms, thus opening opportunities for using it as a future medical treatment. A COVID-19 infection leads to an increased production of protein-rich exudate in the alveolar space, together with intravascular coagulation within lung vessels, and results in damage to type I and type II pneumocytes and lung endothelial lesions. Lower synthesis of lung surfactant coincides with reduced gaseous exchange functions, thus compromising the ability of the lungs to remain flexible. The alveolar infection by SARS-CoV-2 leads to pyogenic inflammation as well as elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β. The inflammation site attracts white blood cells through chemotaxis after pro-inflammatory cytokine levels rise, and this process leads to increased ROS production. The increase in electron transport chain (ETC)-related enzyme activity occurs because of this process. H2O2 production by NADPH oxidase becomes catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (SOD), while transition metals such as Fe2+initiate the Fenton reaction, which is supposedly responsible for killing alveolar pneumocytes type I and type II. The disrupted alveolar gaseous exchange, combined with alveolar collapse will create ischemic-like conditions that enhance myocardial infarction, leading to death. Recent scientific evidence suggests that melatonin has the capability of improving cardiac function during ischemic conditions, as seen in the case of ISO-induced myocardial injuries in rats. ISO or isoproterenol is a synthetic catecholamine and also an agonist of the β-adrenergic receptor, which is known to cause myocardial infarction in rats [91]. Heart mitochondrial oxidative stress occurs due to ISO consumption, and such oxidative stress can result in cardiac conditions. The receptor-dependent and receptor-separate pathways function through melatonin to decrease oxidative stress generation, which protects the heart. Through its regulatory mechanism, melatonin helps restore both cardiac output and blood pressure levels that have changed due to myocardial injuries, thus enabling proper oxygen delivery and cardiac stability [88], as presented in the schematic diagram (fig. 11).

CONCLUSION

Melatonin exhibits possible effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2. As a result of its antioxidant properties, melatonin functions well for individuals who have viral infections. The protection of heart function occurs through melatonin, together with its metabolites, which also prevent the development of cardiomyopathy. Healthcare effectiveness, along with the probability of patient recovery, increases through the use of melatonin therapy. Additional research needs to be conducted regarding new therapeutic approaches using melatonin derivatives that save lives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Dr. Arnab Kumar Ghosh for his help and guidance.

ABBREVIATIONS

TPH, tryptophan hydroxylase; AAA, aryl acylamidase; AAAD, aromatic amino acid decarboxylase; Trypansomal cells require two enzymes for melatonin synthesis: N-acetyltransferase, designated as NAT; hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase, abbreviated as HIOMT.

AFMK stands for N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine. The production of such metabolites occurs through enzymatic and oxidative mechanisms after melatonin metabolism.

AMK stands for N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine. The antioxidant properties of this metabolite emerge when AFMK generates the substance.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Arnab Kumar Ghosh: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Resources, Writing-review and editing, Project Administration; Shashanka Debnath: Writing-original draft, Investigation, Data collection, Abhijit Ghosh: Writing-original draft, data collection, Visualisation; Subhamoy Banerjee: Writing-original draft, data curation, conceptualization.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Authors have no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5, PMID 31986264, PMCID PMC7159299.

Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Correction to: clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1294-7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06028-z, PMID 32253449, PMCID PMC7131986.

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585, PMID 32031570, PMCID PMC7042881.

Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802-10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950, PMID 32211816, PMCID PMC7097841.

Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):811-8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017, PMID 32219356, PMCID PMC7101506.

Tam CF, Cheung KS, Lam S, Wong A, Yung A, Sze M. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(4):e006631. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.120.006631, PMID 32182131.

Alsaidan AA, Al Kuraishy HM, Al Gareeb AI, Alexiou A, Papadakis M, Alsayed KA. The potential role of SARS-CoV-2 infection in acute coronary syndrome and type 2 myocardial infarction (T2mi): intertwining spread. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11(3):e798. doi: 10.1002/iid3.798, PMID 36988260, PMCID PMC10022425.

Justyn M, Yulianti T, Wilar G. Long-term COVID-19 effect to endothelial damage trough extrinsic apoptosis led to cardiovascular disease progression: an update review. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(6)60-8. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i6.48889.

Chen L, Li X, Chen M, Feng Y, Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(6):1097-100. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa078, PMID 32227090, PMCID PMC7184507.

Younis NK, Zareef RO, Al Hassan SN, Bitar F, Eid AH, Arabi M. Hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients: pros and cons. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Nov 19;11:597985. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.597985, PMID 33364965, PMCID PMC7751757.

Tan DX, Hardeland R, Manchester LC, Paredes SD, Korkmaz A, Sainz RM. The changing biological roles of melatonin during evolution: from an antioxidant to signals of darkness sexual selection and fitness. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2010;85(3):607-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00118.x, PMID 20039865.

Reiter RJ, Paredes SD, Manchester LC, Tan DX. Reducing oxidative/nitrosative stress: a newly discovered genre for melatonin. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44(4):175-200. doi: 10.1080/10409230903044914, PMID 19635037.

Tengattini S, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Terron MP, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Cardiovascular diseases: protective effects of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2008;44(1):16-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00518.x, PMID 18078444.

Samantaray S, Das A, Thakore NP, Matzelle DD, Reiter RJ, Ray SK. Therapeutic potential of melatonin in traumatic central nervous system injury. J Pineal Res. 2009;47(2):134-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00703.x, PMID 19627458, PMCID 11877319.

Jou MJ, Peng TI. Visualization of melatonins multiple mitochondrial levels of protection against mitochondrial Ca2+-mediated permeability transition and beyond in rat brain astrocytes. Biophys J. 2010;98(3):378a. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.2038.

Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies V, Reiter RJ, Ruggiero FM. Melatonin, cardiolipin and mitochondrial bioenergetics in health and disease. J Pineal Res. 2010;48(4):297-310. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00759.x, PMID 20433638.

Waran K, Baby LP, Johnson N, John S, RS. Prospective observational study on myocardial infarction in relationship with various risk factors. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9(9):156. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2016.v9s3.13735.

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Manchester LC, Qi W. Biochemical reactivity of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: a review of the evidence. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2001;34(2):237-56. doi: 10.1385/CBB:34:2:237, PMID 11898866.

Long L, Han X, Ma X, Li K, Liu L, Dong J. Protective effects of fisetin against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(5):3177-88. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8576, PMID 32266013, PMCID PMC7132235.

Ferrario CM, Chappell MC, Tallant EA, Brosnihan KB, Diz DI. Counterregulatory actions of angiotensin-(1-7). Hypertension. 1997;30:535-41. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.3.535, PMID 9322978.

Dellegar SM, Murphy SA, Bourne AE, DiCesare JC, Purser GH. Identification of the factors affecting the rate of deactivation of hypochlorous acid by melatonin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257(2):431-9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0438, PMID 10198231.

Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417(6891):822-8. doi: 10.1038/nature00786, PMID 12075344.

Tesoriere L, Avellone G, Ceraulo L, Arpa D, Allegra M, Livrea MA. Oxidation of melatonin by oxoferryl hemoglobin: a mechanistic study. Free Radic Res. 2001;35(6):633-42. doi: 10.1080/10715760100301161, PMID 11811517.

Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Manchester LC, Yan MT, El Sawi M, Sainz RM. Chemical and physical properties and potential mechanisms: melatonin as a broad-spectrum antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(2):181-97. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394443, PMID 11899100.

Tan DX, Hardeland R, Manchester LC, Poeggeler B, Lopez Burillo S, Mayo JC. Mechanistic and comparative studies of melatonin and classic antioxidants in terms of their interactions with the ABTS cation radical. J Pineal Res. 2003;34(4):249-59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00037.x, PMID 12662346.

Shreen S, Nooreen N, Zahid U, Maleeha A, Samreen A, Zoheb M. Effect of melatonin in post-stroke recovery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(4)77-81. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i4.43466.

Reiter RJ. Melatonin: lowering the high price of free radicals. News Physiol Sci. 2000;15(5):246-50. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.5.246, PMID 11390919.

Leon J, Acuna Castroviejo D, Escames G, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin mitigates mitochondrial malfunction. J Pineal Res. 2005;38(1):1-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00181.x, PMID 15617531.

Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):586-90. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9, PMID 32125455, PMCID PMC7079879.

Zhang R, Wang X, Ni L, Di X, Ma B, Niu S. COVID-19: melatonin as a potential adjuvant treatment. Life Sci. 2020 Jun 1;250:117583. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117583, PMID 32217117, PMCID PMC7102583.

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531-8. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9, PMID 32161990, PMCID PMC7087935.

Karasek M. Melatonin, human aging and age-related diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39(11-12):1723-9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.04.012, PMID 15582288.

Li Y, Hu Y, Yu J, Ma T. Retrospective analysis of laboratory testing in 54 patients with severe or critical type 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Lab Investig. 2020;100(6):794-800. doi: 10.1038/s41374-020-0431-6, PMID 32341519, PMCID PMC7184820.

Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5, PMID 32325026, PMCID PMC7172722.

Richardson MA, Gupta A, O Brien LA, Berg DT, Gerlitz B, Syed S. Treatment of sepsis-induced acquired protein C deficiency reverses angiotensin converting enzyme-2 inhibition and decreases pulmonary inflammatory response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325(1):17-26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130609, PMID 18182560.

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel corona virus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844-7. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768, PMID 32073213, PMCID PMC7166509.

Schmidt Arras D, Rose John S. IL-6 pathway in the liver: from physiopathology to therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1403-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.004, PMID 26867490.

Liu X, Liu X, Xu Y, Xu Z, Huang Y, Chen S. Ventilatory ratio in hypercapnic mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1297-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0373LE, PMID 32203672, PMCID PMC7233337.

Rodriguez B, Trayanova N, Noble D. Modeling cardiac ischemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1080(1):395-414. doi: 10.1196/annals.1380.029, PMID 17132797, PMCID PMC3313589.

Alhogbani T. Acute myocarditis associated with novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36(1):78-80. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.78, PMID 26922692.

Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi Zoccai G, Der Nigoghossian C, Zidar DA, Haythe J, Brodie D, Beckman JA, Kirtane AJ, Stone GW, Krumholz HM, Parikh SA. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2352–71. doi 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031.

Li L, Huang Q, Wang DC, Ingbar DH, Wang X. Acute lung injury in patients with COVID-19 infection. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(1):20-7. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.16, PMID 32508022, PMCID PMC7240840.

Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in non-phagocytic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65(3):337-40. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.337, PMID 10080536.

Delgado Roche L, Mesta F. Oxidative stress as key player in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection. Arch Med Res. 2020;51(5):384-7. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.04.019, PMID 32402576, PMCID PMC7190501.

Ardes D, Boccatonda A, Rossi I, Guagnano MT, Santilli F, Cipollone F. COVID-19 and RAS: unravelling an unclear relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):3003. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083003, PMID 32344526.

Khomich OA, Kochetkov SN, Bartosch B, Ivanov AV. Redox biology of respiratory viral infections. Viruses. 2018;10(8):392. doi: 10.3390/v10080392, PMID 30049972.

Saleh J, Peyssonnaux C, Singh KK, Edeas M. Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Mitochondrion. 2020 Sep;54:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.008, PMID 32574708, PMCID PMC7837003.

Peterhans E. Sendai virus stimulates chemiluminescence in mouse spleen cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;91(1):383-92. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)90630-2, PMID 229848.

Reiter RJ, Tan DX. Melatonin: a novel protective agent against oxidative injury of the ischemic/reperfused heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58(1):10-9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00827-1, PMID 12667942.

Cecchini R, Cecchini AL. SARS-CoV-2 infection pathogenesis is related to oxidative stress as a response to aggression. Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:(110102). doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110102, PMID 32721799, PMCID PMC7357498.

Ng MP, Lee JC, Loke WM, Yeo LL, Quek AM, Lim EC. Does influenza a infection increase oxidative damage? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(7):1025-31. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5907, PMID 24673169.

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Allegra M. Melatonin: reducing molecular pathology and dysfunction due to free radicals and associated reactants. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2002;23 Suppl 1:3-8. PMID 12019343.

Taube H. Mechanisms of oxidation with oxygen. J Gen Physiol. 1965;49(1)Suppl:29-52. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.1.29, PMID 5859925, PMCID PMC2195455.

Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Biologically relevant metal ion-dependent hydroxyl radical generation an update. FEBS Lett. 1992;307(1):108-12. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80911-y, PMID 1322323.

Halliwell B. Oxidants and human disease: some new concepts. FASEB J. 1987;1(5):358-64. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.1.5.2824268, PMID 2824268.

Gutteridge JM. Hydroxyl radicals iron oxidative stress and neurodegenerationa. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;738(1):201-13. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21805.x.

Valencia AM, Abrantes MA, Hasan J, Aranda JV, Beharry KD. Reactive oxygen species biomarkers of microvascular maturation and alveolarization and antioxidants in oxidative lung injury. React Oxyg Species (Apex). 2018;6(18):373-88. doi: 10.20455/ros.2018.867, PMID 30533532.

Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1017-32. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3, PMID 32651579, PMCID PMC11972613.

Alharthy A, Faqihi F, Memish ZA, Karakitsos D. Lung injury in COVID-19-an emerging hypothesis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(15):2156-8. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00422, PMID 32709193, PMCID PMC7393669.

Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis GJ, Van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus a first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631-7. doi: 10.1002/path.1570, PMID 15141377, PMCID PMC7167720.

Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Rackley CR, Bowie EJ, Keene DR, Stripp BR. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(7):3025-36. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782, PMID 23921127, PMCID PMC3696553.

Rivellese F, Prediletto E. ACE2 at the centre of COVID-19 from paucisymptomatic infections to severe pneumonia. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(6):102536. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102536, PMID 32251718, PMCID PMC7195011.

Ucar M, Korkmaz A, Reiter RJ, Yaren H, Oter S, Kurt B. Melatonin alleviates lung damage induced by the chemical warfare agent nitrogen mustard. Toxicol Lett. 2007;173(2):124-31. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.07.005, PMID 17765411.

Nicholls JM, Poon LL, Lee KC, Ng WF, Lai ST, Leung CY. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1773-8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13413-7, PMID 12781536, PMCID PMC7112492.

Tian H, Liu Y, Li Y, Wu CH, Chen B, Kraemer MU. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 d of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6491):638-42. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6105, PMID 32234804.

Barton LM, Duval EJ, Stroberg E, Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. COVID-19 autopsies Oklahoma USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(6):725-33. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062, PMID 32275742, PMCID PMC7184436.

Selvarani G, Nagasundar G, Nisamudeen KM, Balasubramanian S, Veeramani SR, Natarajan M. Diagnosis and management of arrhythmias in COVID-19 patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital: outcomes and clinical implications. International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Review. 2023;15(3):262-70.

Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(5):405-7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012, PMID 32362390.

Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian Malhami R, Perkmann T, Van Loo G. Identification of oxidative stress and toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008;133(2):235-49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043, PMID 18423196, PMCID PMC7112336.

Gilad E, Cuzzocrea S, Zingarelli B, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Melatonin is a scavenger of peroxynitrite. Life Sci. 1997;60(10):PL169-74. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00008-8, PMID 9064472.

Topal T, Oztas Y, Korkmaz A, Sadir S, Oter S, Coskun O. Melatonin ameliorates bladder damage induced by cyclophosphamide in rats. J Pineal Res. 2005;38(4):272-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00202.x, PMID 15813904.

Lopez Burillo S, Tan DX, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ. Melatonin xanthurenic acid, resveratrol EGCG vitamin C and α‐lipoic acid differentially reduce oxidative DNA damage induced by Fenton reagents: a study of their individual and synergistic actions: synergistic actions of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2003;34(4):269-77. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00041.x, PMID 12662349.

Sudnikovich EJ, Maksimchik YZ, Zabrodskaya SV, Kubyshin VL, Lapshina EA, Bryszewska M. Melatonin attenuates metabolic disorders due to streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;569(3):180-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.018, PMID 17597602.

Baydas G, Canatan H, Turkoglu A. Comparative analysis of the protective effects of melatonin and vitamin E on streptozocin-induced diabetes mellitus. J Pineal Res. 2002;32(4):225-30. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.01856.x, PMID 11982791.

Wahab MH, Akoul ES, Abdel Aziz AA. Modulatory effects of melatonin and vitamin E on doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in ehrlich ascites carcinoma bearing mice. Tumori. 2000;86(2):157-62. doi: 10.1177/030089160008600210, PMID 10855855.

Montilla P, Cruz A, Padillo FJ, Tunez I, Gascon F, Munoz MC. Melatonin versus vitamin E as protective treatment against oxidative stress after extrahepatic bile duct ligation in rats. J Pineal Res. 2001;31(2):138-44. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2001.310207.x, PMID 11555169.

Hsu C, Han B, Liu M, Yeh C, Casida JE. Phosphine induced oxidative damage in rats: attenuation by melatonin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28(4):636-42. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00277-4, PMID 10719245.

Gultekin F, Delibas N, Yasar S, Kilinc I. In vivo changes in antioxidant systems and protective role of melatonin and a combination of vitamin C and vitamin E on oxidative damage in erythrocytes induced by chlorpyrifos ethyl in rats. Arch Toxicol. 2001;75(2):88-96. doi: 10.1007/s002040100219, PMID 11354911.

Rosales Corral S, Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Valdivia Velazquez M, Martinez Barboza G, Acosta Martinez JP. Orally administered melatonin reduces oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines induced by amyloid-β peptide in rat brain: a comparative in vivo study versus vitamin C and E. J Pineal Res. 2003;35(2):80-4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00057.x, PMID 12887649.

Anwar MM, Meki AR. Oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: effects of garlic oil and melatonin. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2003;135(4):539-47. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00114-4, PMID 12890544.

Winiarska K, Fraczyk T, Malinska D, Drozak J, Bryla J. Melatonin attenuates diabetes-induced oxidative stress in rabbits. J Pineal Res. 2006;40(2):168-76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00295.x, PMID 16441554.

Gitto E, Reiter RJ, Cordaro SP, La Rosa M, Chiurazzi P, Trimarchi G. Oxidative and inflammatory parameters in respiratory distress syndrome of preterm newborns: beneficial effects of melatonin. Am J Perinatol. 2004;21(4):209-16. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828610, PMID 15168319.

Gitto E, Reiter RJ, Sabatino G, Buonocore G, Romeo C, Gitto P. Correlation among cytokines, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and modality of ventilation in preterm newborns: improvement with melatonin treatment. J Pineal Res. 2005;39(3):287-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00251.x, PMID 16150110.

Mukherjee D, Roy SG, Bandyopadhyay A, Chattopadhyay A, Basu A, Mitra E. Melatonin protects against isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in the rat: antioxidative mechanisms. J Pineal Res. 2010;48(3):251-62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00749.x, PMID 20210856.

Abadi SH, Shirazi A, Alizadeh AM, Changizi V, Najafi M, Khalighfard S. The effect of melatonin on superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activity and malondialdehyde levels in the targeted and the non-targeted lung and heart tissues after irradiation in xenograft mice colon cancer. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2018;11(4):326-35. doi: 10.2174/1874467211666180830150154, PMID 30173656.

Bindoli A, Rigobello MP, Deeble DJ. Biochemical and toxicological properties of the oxidation products of catecholamines. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13(4):391-405. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90182-g, PMID 1398218.

Chattopadhyay A, Biswas S, Bandyopadhyay D, Sarkar C, Datta AG. Effect of isoproterenol on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes of myocardial tissue of mice and protection by quinidine. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;245(1-2):43-9. doi: 10.1023/a:1022808224917, PMID 12708743.

Armagan A, Uz E, Yilmaz HR, Soyupek S, Oksay T, Ozcelik N. Effects of melatonin on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat testis. Asian J Androl. 2006;8(5):595-600. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00177.x, PMID 16752005.

Buffinton GD, Christen S, Peterhans E, Stocker R. Oxidative stress in lungs of mice infected with influenza a virus. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;16(2):99-110. doi: 10.3109/10715769209049163, PMID 1321077.

Amatore D, Sgarbanti R, Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Limongi D, Civitelli L. Influenza virus replication in lung epithelial cells depends on redox-sensitive pathways activated by NOX4-derived ROS. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17(1):131-45. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12343, PMID 25154738.

Mayo JC, Tan DX, Sainz RM, Lopez Burillo S, Reiter RJ. Oxidative damage to catalase induced by peroxyl radicals: functional protection by melatonin and other antioxidants. Free Radic Res. 2003;37(5):543-53. doi: 10.1080/1071576031000083206, PMID 12797476.