Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 7, 25-32Original Article

AN ETHNOMEDICINAL STUDY OF CERTAIN WILD AND CULTIVATED FRUIT VEGETABLES OF GENUS ABELMOSCHUS MEDIK

SHINDE SACHIN S.1*, KESHAV B. NARWADE2, SHRIMANT D. RAUT3, LAXMIKANT H. KAMBLE4

*1Department of Botany, Vidarbha College of Arts, Commerce, and Science Jiwati District Chandrapur, India. 2Department of Botany, Degloor College, Degloor-431717, Maharashtra, India. 3Department of Botany, Pratibha Niketan Mahavidhyalaya Nanded-Waghala-431604, Maharashtra, India. 4School of Life Sciences, Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University, Nanded, India

*Corresponding author: Shinde Sachin S.; *Email: ssshinde493@gamil.com

Received: 01 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 02 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Southeast Asia's agricultural diversity is shaped by its varied agro-climatic conditions, including diverse farming practices, rainfall patterns, and soil types. India, in particular, is home to a wide range of Abelmoschus species, which are found in cultivated, semi-wild, and wild varieties.

Methods: In this study, four species of the Abelmoschus genus were identified and documented: A. moschatus L., A. manihot L., A. esculentus L., and A. ficulneus L. Data was collected from 280 tribal individuals within the study area.

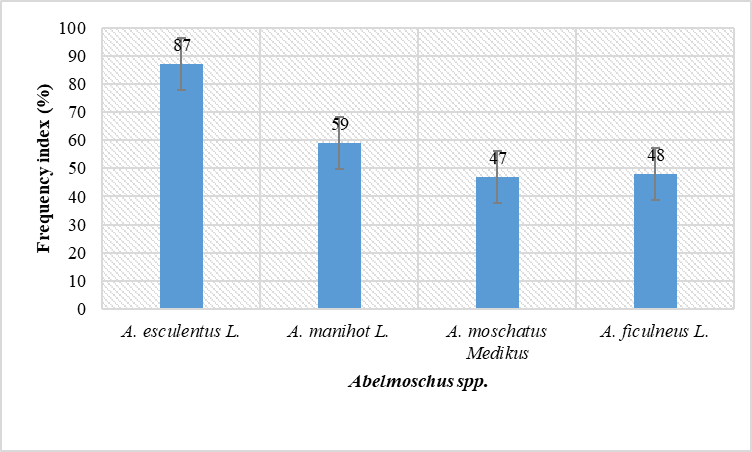

Results: The present study aims to explore the traditional knowledge and utilization of wild and cultivated Abelmoschus fruit vegetables by indigenous communities in the deep tribal pockets of Jiwati Tehsil, Chandrapur district (Maharashtra). Among four species of the Abelmoschus genus, A. esculentus L. (FI-87%) is widely cultivated, while A. manihot L. (FI-59%) and A. moschatus L. (FI-47%) is predominantly wild, with occasional cultivation. In contrast, A. ficulneus L. (FI-48%) remains strictly wild. Fruits from these species are commonly incorporated into vegetable-based meals, serving as a significant dietary component.

Conclusion: These fruit vegetables are known for their ethnomedical and pharmacological benefits, including their use in controlling blood sugar levels and improving digestion. Documenting these practices can provide valuable insights into sustainable food sources, medicinal plant conservation, and potential applications in modern healthcare.

Keywords: Abelmoschus spp., Wild vegetables, Tribal people, A. moschatus L

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i7.54833 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Abelmoschus Medik is a genus that includes approximately 50 known species worldwide [1]; however, taxonomic uncertainties persist due to synonyms, misidentifications, and species with unclear status [2]. Hochreutiner [3] identified fourteen species, but Van Borssum-Waalkes [4] only identified six. These comprised three wild varieties (A. ficulneus L., A. crinitus L., and A. angulosus L.) and three cultivated species (A. moschatus L., A. manihot L., and A. esculentus L. Paul and Nair [5] identified seven species in India. The classification scheme developed by the International Okra Workshop [6] included nine species; however, two more species were later added by John et al. [7] along with Sutar et al. [8]: A. palianus L. and A. enbeepeegearense L. Currently, India is home to seven species, three subspecies, and five varieties of Abelmoschus.

The diverse agroclimatic conditions of Southeast Asia, including variations in soil types and rainfall patterns, have fostered the rich diversity of Abelmoschus species. The growth patterns of this genus are diverse, ranging from shrubs to annual and perennial plants, and are characterized by long-petioled, hastate, or palmately lobed leaves that may be glandular or glabrous. Its flowers display a spectrum of colors, including white, deep yellow, pink, and red [7-9]. Species of Abelmoschus, such as the commercially significant A. esculentus L., are distributed across India, from the southern region and western hills [9] to the central Himalayan range [10]. Recent studies highlight the diverse applications of Abelmoschus varieties, valued for their exceptional nutritional and medicinal properties, particularly in their seeds and foliage [11].

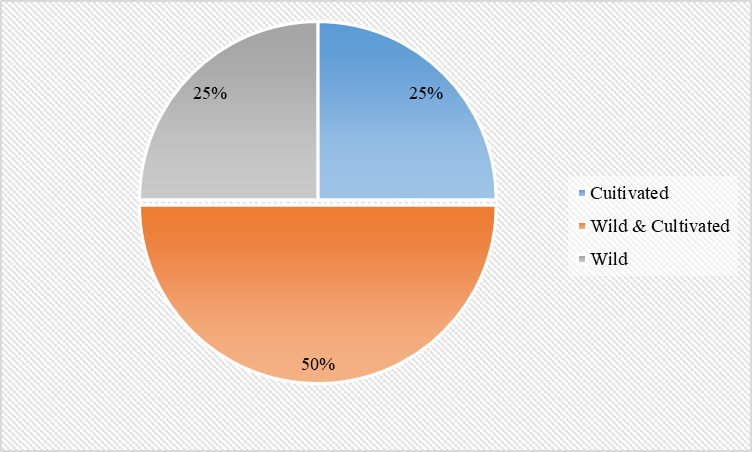

India's diverse agroclimatic zones support the growth of multiple Abelmoschus species, with the country being home to eight identified species [12]. This study reports the presence of four Abelmoschus species (fig. 2). The only one that is cultivated within them is A. esculentus L. A. ficulneus L. is a true wild species, whereas A. moschatus L. and A. manihot L. are wild species that are also cultivated for their fragrant seeds [4]. Wild vegetables hold significant cultural and dietary value, often playing a vital role in folklore, particularly on special occasions, and contributing to a balanced, nutritious diet [13]. Their importance extends beyond sustenance, as they are also associated with traditional healing practices. As a result, ethnodirected research can greatly enhance efforts to discover new food sources and develop innovative medicinal applications. This study aimed to explore the traditional knowledge and utilization of both wild and domesticated Abelmoschus species among indigenous communities residing in remote tribal regions of the study area. By documenting how these communities have historically cultivated, harvested, and consumed these plants, the research provides valuable insights into their nutritional, medicinal, and cultural significance. Understanding these traditional practices can inform conservation efforts, sustainable agriculture, and the potential for further scientific exploration of Abelmoschus species for broader applications in food security and medicine.

The present study aimed to provide valuable insights into ethnomedicinal fruit vegetables of genus Abelmoschus as sustainable food sources and their potential medicinal applications in modern healthcare.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

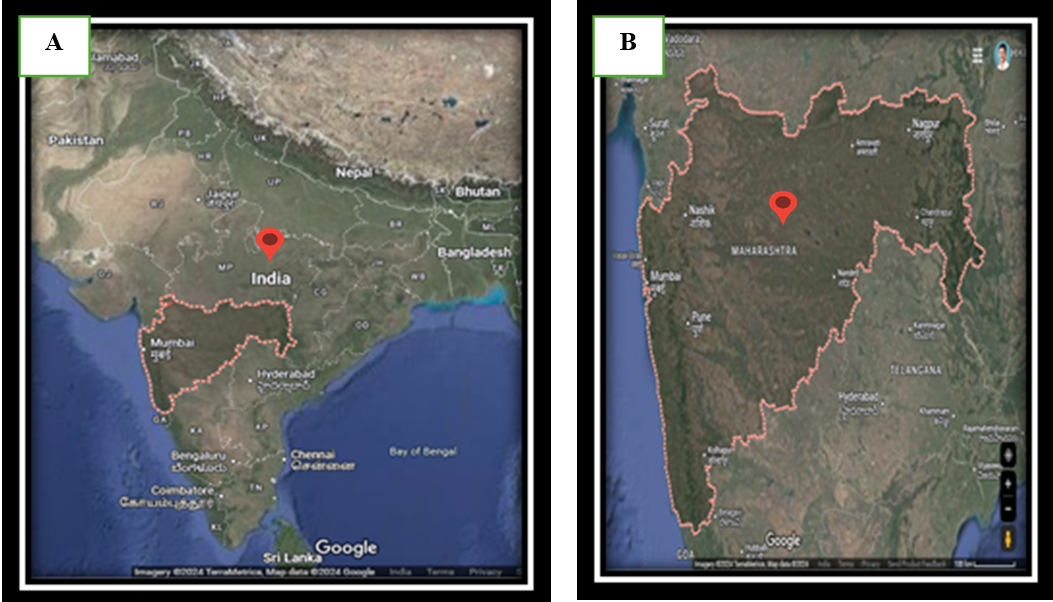

The current investigation was carried out in multiple villages within Jiwati Tehsil in Chandrapur District, Maharashtra, India (fig. 1-A-E). Chandrapur District, located in the eastern region of Maharashtra, is known for its rich natural resources, diverse geography, and historical significance. It spans a total area of 11,443 square kilometers and lies between latitudes 19° 30' and 20° 45' North and longitudes 78° 46' and 80° East. The district experiences a predominantly dry and partly humid climate, receiving an average annual rainfall of approximately 1300 mm [14]. Winters are characterized by moderate temperatures ranging between 18 °C and 30 °C, creating pleasant weather conditions. Around 37% of the district is covered by dense forests, and it forms part of the Deccan Plateau, which is home to dry tropical deciduous forests. Physiographically, Chandrapur District (fig. 1C) is divided into two distinct regions: the Upland Hilly Zone and the Plain Zone. The plain region, primarily found around the Wardha River, features a flat and widely dispersed landscape. In the northern section of the Wainganga Valley (Brahmapuri Taluka), extensive alluvial floodplains dominate the terrain, while the southern part of the valley transitions into a rolling topography with scattered hills. The southwestern portion of the district, within Penganga Valley, has limited flat terrain. The Upland Hilly Zone is situated between the Wardha and Wainganga Rivers, characterized by rugged and elevated landscapes [15].

The present study was conducted in Jiwati Tehsil, a sub-district in Chandrapur District, Maharashtra, India (fig. 1D). According to the 2011 Census, Jiwati Tehsil has a sub-district code of 04076 and spans a total area of 559 km². With 61,820 residents, it has a population density of 110.6 people per square kilometer. The tehsil comprises approximately 82 villages, where most residents live in rural communities and primarily depend on subsistence and wild farming for their livelihoods [16]. The region's climate varies, encompassing both temperate and subtropical zones, which support diverse agricultural practices. For this study, extensive field visits were conducted in 15 rural villages within Jiwati Tehsil (fig. 1E), including Pudiyal-Mohda, Gudsela, Wani Bk., Wani Kh., Yellapur, Lambori, Kumbhezari, Dhonda-Arjuni, Tekamandwa, Shengaon, Asapur, Pallezari, Jiwati, Kusumbi, and Ambezari. The primary objective was to collect and document wild and cultivated fruit vegetables belonging to the Abelmoschus genus. Jiwati Tehsil is predominantly inhabited by various tribal communities, including the Gond, Kolam, Pradhan, and Andh tribes, who have a rich tradition of utilizing wild plant resources for food and medicinal purposes. Their deep-rooted ethnobotanical knowledge plays a crucial role in the conservation and sustainable use of indigenous plant species.

Fig. 1: Map showing the study area (A-India, B-Maharashtra State, C-Chandrapur District, D-Jiwati Tehsil, and E-Fields visited during the study)

Plants, data collection and analysis

In the present study, four vegetables of genus Abelmoschus were studied. The detailed taxonomy of Abelmoschus fruit vegetables, as described by Naik [17], is as follows:

Abelmoschus esculentus L.

This stout, nearly glabrous, and erect annual herb grows to a height of 0.3–1.5 m. The leaves are ovate-cordate, measuring 8–10 cm across, with three to nine or more lobes. These lobes may be triangular or oblong-lanceolate with dentate-serrate margins. The stipules are either whole or bifid, linear, and 0.5–1 cm long. The plant features robust pedicels, 2–3 cm in length, with axillary, solitary flowers measuring 5–8 cm across. The calyx is 1.5–3 cm long, hairy, and ends in five distinct teeth. The corolla is 5–7 cm long, golden-yellow with a crimson center. The fruit is a five-pointed capsule, beaked, either hairy or glossy, ranging from 10 to 30 cm in length, and becoming woody when mature. The seeds are reniform, greenish-brown, and glabrous, with concentric rings of fine hairs. This species is cultivated for its soft, edible fruits, commonly consumed as vegetables, and for fibers extracted from the stem. Flowering and fruiting occur almost year-round [17].

Abelmoschus manihot L.

These hispid herbs are upright, ranging in height from 0.5 to 1.5 meters. The petioles measure 4–20 cm in length, while the ovate-suborbicular leaves range from 7.5–15 × 7.5–20 cm, with a cordate base and 3–7 palmately lobed margins. The lanceolate stipules, typically 1.5–2 cm long, are often three-lobed. The plant produces axillary flowers, either solitary or arranged in terminal racemes, measuring 6–10 cm in diameter. The pedicels are sturdy, 2–5 cm long, and hirsute, with bracteoles measuring 2–3 cm in length. The calyx is also hirsute, 4–4.5 cm long, and ends in three teeth. The oblong yellow petals, 4–8 cm long, have a dark brown or purple base. The fruit is an ovoid-oblong, thickly bristly, beaked capsule measuring 5–6 cm in length. The reniform-globose seeds are dark brown, 3–4 mm across, and have concentric rings of fine hairs. This species is uncommon and found in hill forests under tree shade. It flowers and bears fruit from September to December [17].

Abelmoschus moschatus L.

This erect, tomentose herb grows to a height of 1–2.5 meters. The petioles measure 2–10 cm in length, while the linear stipules are 0.5–1 cm long, ciliate, and delicate. The leaves are oblong to orbicular, measuring 3–8 × 0.5–4.5 cm, with 3–5 lobes; the lobes are triangular-acute with serrated edges. The plant produces axillary, solitary flowers that form a short raceme measuring 5–8 cm across. The pedicels are hispid, 0.5–1 cm long, with filiform bracts approximately 1 cm in length and filiform bracteoles 1–1.5 cm long, ciliate, and hispid. The calyx is heavily hispid on the exterior and slightly larger than the bracteoles. The oblanceolate petals are golden, 3–5 cm long, with a dark purple base. The capsules are oval, 1–1.5 × 1–1.2 cm, acuminate, and may be glabrous or villous. The seeds are reniform, greyish-brown, with a faint golden muricate texture, and emit a fragrance when crushed. This species is likely cultivated for its fragrant seeds and occasionally escapes cultivation. Flowering and fruiting occur from September to December [17].

Abelmoschus ficulneus L.

These erect or procumbent woody herbs, with hispid stems, grow to a height of 1–1.5 meters. The leaves are orbicular-cordate, 4–9.5 cm wide, angled, or palmately 3–5 lobed. The lobes are oblong, pointed or obtuse, serrate-dentate, and hispid, particularly along the veins on the underside. Axillary flowers, measuring 3–5 cm in diameter, appear either solitary or in terminal racemes. The pedicels are robust, 1–2 cm long. The plant has 5–6 ovate-lanceolate bracteoles, 1–1.5 cm long, thickly greyish-tomentose, and deciduous. The calyx, 1.5–2 cm long, is also deciduous, highly hispid, and ends in five small teeth. The corolla, 3–3.5 cm long, is white on the inside and pink on the outside. The capsule is ovoid, 2–3 cm long, 5-angled, thickly bristly, and short-beaked. The seeds are reniform-globose, black, and slightly hairy. This species is commonly found along forest edges and on bunds surrounding fields. Flowering and fruiting occur from September to January [17].

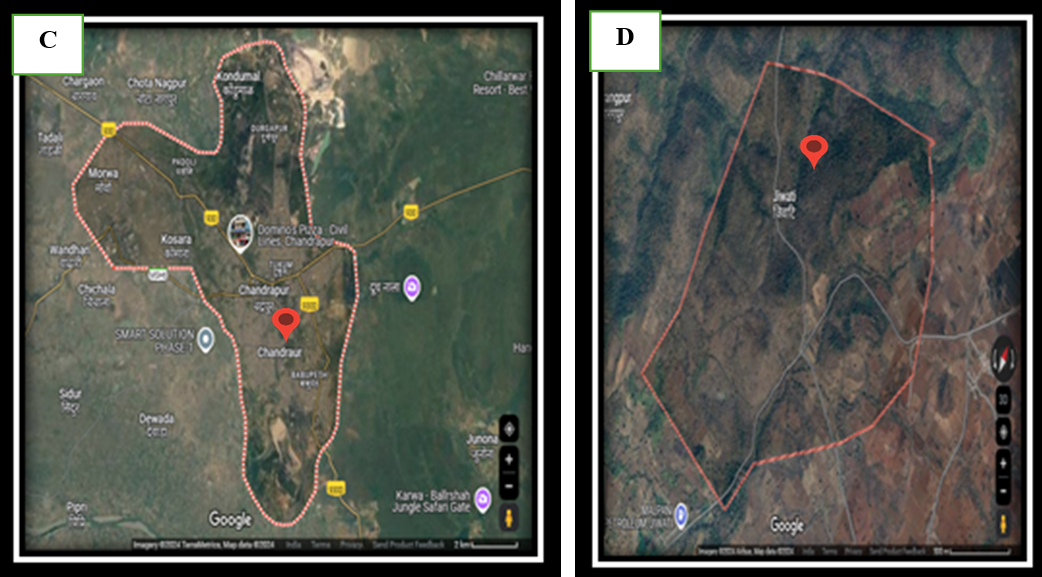

Fig. 2: A plant habitat with flowers and fruits: A. esculentus L. (A-B), A. manihot L. (C-D), A. moschatus L. (E-F), and A. ficulneus L. (G-H)

To document the vegetable species utilized by tribal communities in the study area, a comprehensive ethnobotanical survey of Abelmoschus fruit crops was conducted across multiple villages in Jiwati Tehsil, Chandrapur District, between June 2023 and February 2025. The study involved systematic field visits to various villages, where data was collected from indigenous groups, including the Gond, Kolam, Pradhan, and Andh communities. Additionally, individuals familiar with these vegetables or actively involved in their collection and trade were interviewed. A semi-structured questionnaire was employed to facilitate data collection, ensuring a balance between guided inquiry and open-ended discussions. Before each interview, verbal consent was obtained from participants, respecting ethical research practices and ensuring voluntary participation. The interviews involved 280 informants in all, with ages ranging from 20 to 90, including 94 males and 186 females. The majority of participants (n = 151) were over 60 y old, followed by individuals aged 36–59 y (n = 91), while the youngest group, aged 20–35 y, comprised the smallest portion (n = 38). Participants were questioned about the regional names of widely used wild and farmed vegetables, preparation, and traditional recipes—whether cooked alone or in combination with other ingredients—their taste, role in the local food system, ethnomedicinal applications, and other practical uses.

Collecting plant specimens helped reduce confusion arising from the use of multiple common names for a single species or the application of a single name to different species. In some cases, local informants referred to the same species using two or more commonly used names, leading to inconsistencies in identification. The pressing plant specimens were placed in the college's Department of Botany following verification. Additionally, the International Plant Name Index (IPNI) repository [18] and The Flora of Marathwada [17] were used to confirm the botanical nomenclature of the discovered species. The geographical coordinates of the studied vegetables are Latitude-19.605122’ and Longitude-79.072592’. The plant specimens of these vegetables are identified from the IPNI database, A. esculentus L. (LSID-558006-1), A. manihot L. (WFID-0000510884), A. moschatus L. (LSID-77249689-1) and A. ficulneus L. (LSID-20008221-1) [18]. The mathematical technique modified by Madikizela et al. [19] was used to calculate the frequency index (FI) of species utilization. The following formula was applied: FI=(FC÷N) ×100, where N is the overall number of respondents, FC is the total number of people who participated that specified a specific species, and FI is the frequency index that was computed.

Information on the medicinal uses of wild and cultivated fruit and vegetable species from the genus Abelmoschus was obtained from various tribal communities, including the Gond, Kolam, Pradhan, and Andh, as well as the local population in the study area. Furthermore, databases of scientific literature, including Web of Science, SciFinder, PubChem, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Scopus, were searched to supplement and validate the findings. Relevant data were also collected from published research articles, books, and master's and doctoral theses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

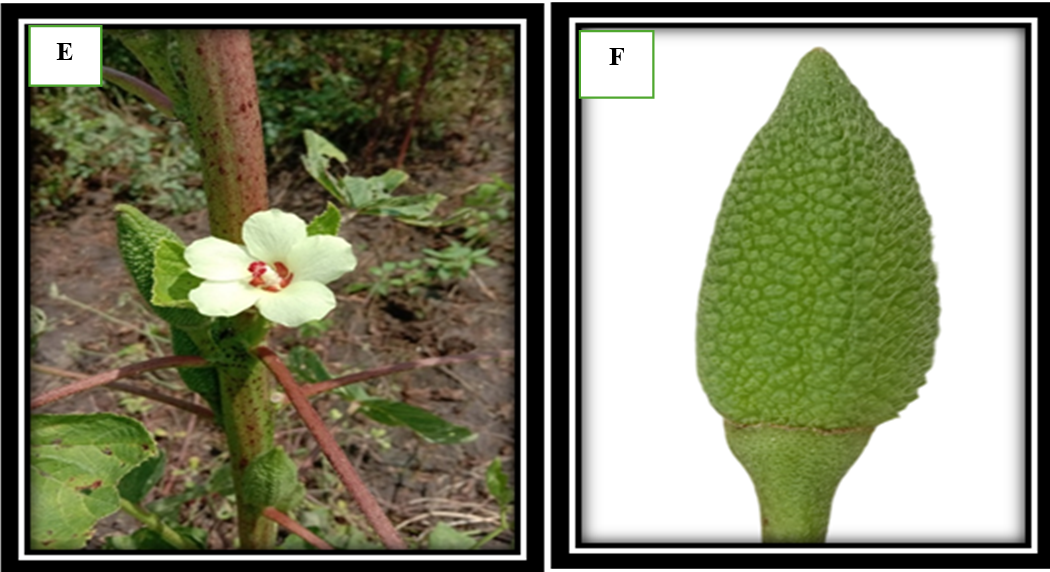

Informants demographic profile

Among the 280 respondents surveyed, the majority were over 60 y old (n = 151), followed by individuals aged 36–59 y (n = 91). The youngest age group, 20–35 y, was the smallest (n = 38). The findings indicated that older individuals consumed wild and cultivated vegetables more frequently than younger age groups. Women constituted a larger proportion of the respondents (n = 186) compared to men (n = 94), as illustrated in fig. 3. In terms of educational background, 47% of the respondents had completed secondary education, 44% had attained tertiary education, and 17% had primary education (table 1).

Table 1: Participant demographics

| Parameter | Specification | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 94 | 34 |

| Female | 186 | 67 | |

| Status | Youth (20–35) | 38 | 14 |

| Community adult (36–59) | 91 | 32 | |

| Elder (>60) | 151 | 54 | |

| Education | None | 28 | 10 |

| Primary | 76 | 27 | |

| Secondary | 132 | 47 | |

| Tertiary | 44 | 16 |

Fig. 3: Respondents involved in the study

Geographical distribution in India

According to Vredebregt [2], species of the genus Abelmoschus are primarily found in tropical and subtropical areas. Of these species, most are native to the Southwest Pacific and South Asia [12]. Their distribution varies based on environmental conditions, geographical range, and morphological diversity [5, 12, 37]. In India, Abelmoschus species are widely dispersed across various phytogeographical zones, from the southern peninsula [9] to the Himalayan area [10].

Among them, A. esculentus L., commonly known as "bhindi" (okra), is a widely farmed variety with soft, tender, and immature fruits. KA and WB are the leading producers of okra in India, followed by UP, AS, BR, OD, and MH [21]. Other Abelmoschus species show diverse regional distributions: A. manihot L. is found in UP, RJ, MP, MH, OD, and CG; A. moschatus L. is distributed in the UK, OD, KL, KA, MH, and AN; while A. ficulneus L. is reported in JK, RJ, MP, CG, MH, TN, AP, and UP [12].

Taxonomic diversity, plant parts used and medicinal applications

To meet the growing demand for nutritionally balanced food, alternative dietary sources must be integrated into the regular diet. The nutritional composition of various vegetables has been extensively studied, with okra emerging as a valuable nutritional resource essential for human health [22]. Okra is particularly rich in proteins, carbohydrates, dietary fiber, fats, minerals, ash, and vitamin C [24]. It is widely known for its tender, succulent pods, which can be roasted, boiled, or fried [25]. Additionally, an alcohol extraction from okra leaves has been shown in trials by [26] along with Kumar et al. [27] to improve renal function, lower proteinuria, relieve renal tubular-interstitial diseases, also neutralize oxygen-free radicals.

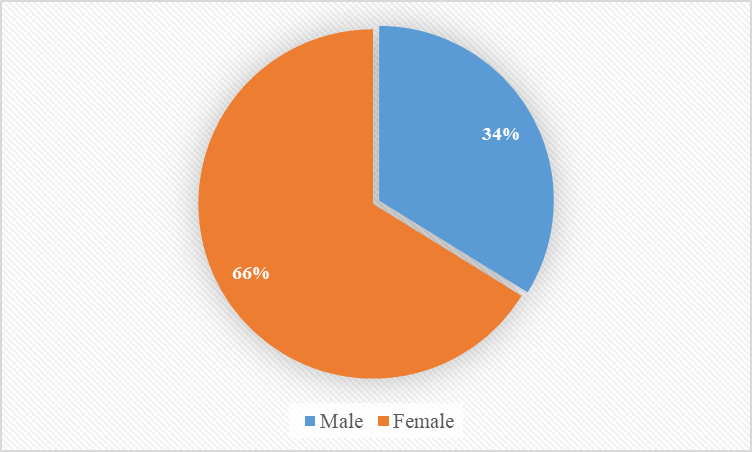

In light of these nutritional and medicinal benefits, this study examined four wild and cultivated fruit vegetables from the genus Abelmoschus, as listed in table 2. These species were identified and documented through ethnobotanical surveys involving 280 tribal individuals from the study area. Among them, the species that is most commonly grown is A. esculentus L., ensuring year-round availability and commercial presence in local markets. Consequently, it exhibited the highest frequency index (87%). A. manihot L. and A. moschatus L. are primarily found in the wild but are occasionally cultivated, with frequency indices of 59% and 47%, respectively [4]. A. ficulneus L., however, remains strictly wild (fig. 4 and table 2). The lower frequency index of A. moschatus L. compared to other okra species is likely due to the hardness and rigidity of its fruit (fig. 5).

Fig. 4: Habit of Abelmoschus Spp

A. ficulneus L. is strictly wild, with a recorded frequency of 48%. The identified fruit vegetables belong to the genus Abelmoschus within the family Malvaceae, with their immature pods commonly used in traditional vegetable preparations. In the study area, tribal communities and local villagers incorporate immature okra pods into a variety of flavorful dishes, including stir-fried okra (Bhindi Fry), okra curry (Bhindi Masala), and stuffed okra (Bharwa Bhindi).

Fig. 5: Frequency index of Abelmoschus spp

Okra is a commercially significant vegetable crop that is grown in India and other tropical and subtropical regions of the world. It is grown on large commercial farms as well as a garden crop. India is a large producer of okra, growing over 3.5 million tons, or 70% of the globe's total production, on 0.35 million hectares [28]. Bhindi is the colloquial name for okra in India. Its flexibility to different moisture conditions, steady yield, and ease of cultivation are the reasons for its appeal. The vegetable is known by different regional names across India [29].

The main reason okra is grown is for its green, spherical, non-fibrous pods, which are harvested while still immature and consumed as a vegetable. It is a staple in South Indian cuisine, often used in gravy-based dishes or sautéed. Immature pods are widely utilized in cooking, while the plant’s stems and roots have additional applications. They are traditionally used to clarify sugarcane juice, which is then processed into gur and brown sugar [29]. Harvested seeds are dried up, grilled, and used as an alternative to coffee in several nations. Furthermore, the paper sector benefits from the crude fiber found in ripened okra fruits and stems. Rich in unsaturated oils like oleic and linoleic acids, the seeds can also be used to make edible oil. This greenish-yellow, food-grade oil, which contains over 40% seed oil, has a nice taste and smell. In terms of nutrition, okra is high in dietary fiber, calcium, potassium, A, C, and K vitamins, and other vital elements that are frequently lacking in the meals of developing countries. It is also known for its antioxidant properties and medicinal benefits, including blood sugar regulation and improved digestion [30].

Other species of Abelmoschus have notable uses. A. manihot L. (Aibika) is a wild species traditionally used to regulate conception and childbirth. It is also believed to stimulate milk production in breastfeeding mothers [31-33]. Mucin, derived from the roots of A. manihot, is utilized in handmade paper production [34]. Ambrette, an aromatic seed oil that is widely used in the fragrance industry, is the primary reason A. moschatus L. is planted [4]. Meanwhile, A. ficulneus L. is traditionally used in treating diarrhea, and a mixture prepared from its fresh root is consumed to address calcium deficiency.

Table 2: Ethnomedicinal and Pharmacological uses of wild and cultivated Abelmoschus spp

| S. No. | Botanical and local name | Family | Distribution in India | Habit | Edible part | Season of availability | Commercially sold | Frequency index (FI) | Method of consumption | Ethnomedicinal and pharmacological uses |

| 1. | A. esculentus L. (Bhendi) | Malvaceae | Karnataka, WB, UP, Assam, Bihar, OD and MH | Cultivated | Fruits | Throughout year | Yes | 87 | Immature pods are consumed boiled, fried, or cooked. [25]. | According to recent research [26-27], leaf extract has important therapeutic qualities that include lowering proteinuria, easing renal tubular-interstitial diseases, getting rid of oxygen-free radicals, and enhancing renal function in general. |

| 2. | A. manihot L. (Ran-Bhendi) | UP, RJ, MP, MH, OD and CG. | Wild and rarely cultivated | Winter | No | 59 | As a vegetable, immature fruits are cut and cooked. Cuts and wounds are treated with a leaf paste. A paste of the bark is used to treat cuts and wounds. |

Wounds and injuries are treated with a bark paste, which is administered fresh every two to three days for approximately three weeks. The flower's juice is used to heal toothaches and chronic bronchitis [35]. | ||

| 3. | A. moschatus L. (Ran-Bhendi) | UK, OD, KL, KA, MH and AN. | Wild and rarely cultivated | Winter | No | 47 | Veggies are prepared by cutting immature fruits into small pieces and boiling them for a longer time due to hard and rigid fruits as compared with other Abelmoschus spp. | The seeds' diuretic medication, demulcent, stomachic, stimulating, cooling process, liqueur, carminative, aphrodisiac, and antibacterial qualities make them far more important medicinally. When chewed, seeds have stomachic, nerve-tonic, and breath-sweetening properties [36]. | ||

| 4. | A. ficulneus L. (Ran-Bhendi) | JK, RJ, MP, CG, MH, TN, AP and UP. | Wild | Winter | No | 48 | Fruits can be consumed as vegetables. To treat stomach pain, a teaspoonful of fruit extract is taken twice daily for three days. | The fruits have been used to cure diarrhea. The smashed fresh root is decocted and used to treat calcium insufficiency [35]. |

CONCLUSION

Currently, there is a growing emphasis on incorporating fruits and vegetables into daily diets. While some species of Abelmoschus remain classified as wild, the genus is widely recognized and cultivated across the world, particularly in India. The findings of this study strongly indicate that people believe vegetables from the Abelmoschus genus possess therapeutic properties. Additionally, this research serves as a valuable reference for the tribal communities of Chandrapur District in selecting vegetables with potential medicinal benefits. A. esculentus L. leaf extract is important for lowering proteinuria, easing renal tubular-interstitial diseases, getting rid of oxygen-free radicals, and enhancing renal function, A. manihot L. flower juice is used to heal toothaches and chronic bronchitis. A. ficulneus L. fruits have been used to cure diarrhea. Whereas A. moschatus L. seeds are used for diuretic medication, demulcent, stomachic, stimulating, cooling process, liqueur, carminative, aphrodisiac, and antibacterial potency. To further explore these benefits, extensive pharmacological research is necessary. A step-by-step approach, including in vivo along with in vitro studies, clinical trials, mechanism-of-action analyses, and safety evaluations, is essential. The creation of powerful new drugs to treat a variety of disorders, from common ailments to more serious medical conditions, may be made possible by such research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors sincerely appreciate the invaluable contributions of all the tribal communities who participated in this study.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

SSS and KBN are responsible for the collection of data and writing of research manuscripts and SDR and LHK are responsible for revising, final drafting, and approval of present research manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Charrier A. Genetic resources of the genus Abelmoschus Med (Okra). IBPGR/84/194.IBPGR; 1984.

Vredebregt IJ. Taxonomic and ecological observations on species of Abelmoschus Medic; 1991. p. 69-76.

Hochreutiner BP. Genres nouveaux et genres discutes de la famille des Malvacees. III. Fioria Mattei ou Hibiscus L. sect. Pterocarpus Garcke. Candollea. 1924;2:87-90.

Van Borssum Waalkes J. Malesian malvaceae revised. Blumea: Biodiversity Evolution and Biogeography of Plants. 1966 Jan 1;14(1):1-213.

Patil P, Sutar S, Malik SK, John J, Yadav S, Bhat KV. Numerical taxonomy of Abelmoschus medik. (Malvaceae) in India. Bangladesh J Plant Taxon. 2015 Dec 28;22(2):87-98. doi: 10.3329/bjpt.v22i2.26070.

Mishra GP, Seth T, Karmakar P, Sanwal SK, Sagar V, Priti SPM. Breeding strategies for yield gains in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus l.). Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Vegetable Crops. 2021 Aug 26;205-33. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66961-4_6.

John KJ, Scariah S, Nissar VA, Bhat KV, Yadav SR. Abelmoschus enbeepeegearense sp. nov. (Malvaceae), an endemic species of okra from Western Ghats, India. Nord J Bot. 2013 May;31(2):170-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.2012.01624.x.

Sutar S, Patil P, Aitawade M, John J, Malik S, Rao S. A new species of Abelmoschus medik. (Malvaceae) from Chhattisgarh, India. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2013 Oct;60(7):1953-8. doi: 10.1007/s10722-013-0023-z.

Sivarajan VV, Pradeep AK. Malvaceae of southern peninsular India: a taxonomic monograph. Daya Books; 1996.

Negi KS, Pant KC. Wild species of Abelmoschus medic. (Malvaceae) from central Himalayan regions of India. J Bombay Nat Hist Soc. 1998;95(1):148-50.

Ngoc TH, Ngoc QN, Tran A, Phung NV. Hypolipidemic effect of extracts from Abelmoschus esculentus L. (Malvaceae) on tyloxapol-induced hyperlipidemia in mice. J Pharm Sci. 2008;35(1-4):42-6.

Bisht IS, Okra BKV (Abelmoschus spp.). Genetic resources chromosome engineering and crop improvement: Vegetable Crops. Vol. 3. 2006 Nov 7. p. 552. doi: 10.1201/9781420009569.

Singh SH, Jain VI, Jain SK, Chandra KA. Medicinal plants and phytochemicals in prevention and management of lifestyle disorders: pharmacological studies and challenges. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021 Dec;14(12):1-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i12.42860.

Geological report on the G-4 exploration for platinum group of elements (PGE) and chromium in district: Chandrapur, State: Maharashtra; 2018.

Shende Rahul R. Groundwater information Chandrapur District Maharashtra (Govt. of India, Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board). 2023;1759/DBR.

https://villageinfo.in/maharashtra/chandrapur/jiwati.html#list-of-villages-in-jiwati. [Last accessed on 14 Jun 2025].

Naik VN. Flora of Marathwada. Aurangabad: Amrut Prakashan; 1998. p. 237-319.

International plant names index (IPNI) database. Available from: http://www.ipni.org/ipni/simpleplantnamesearch. [Last accessed on 06 Jun 2025].

Madikizela B, Ndhlala AR, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Ethnopharmacological study of plants from pondoland used against diarrhoea. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012 May 7;141(1):61-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.053, PMID 22338648.

Velayudhan KC, Upadhyay MP. Collecting okra eggplant and their wild relatives in Nepal. Bull Ressources Phytogenetiques Not Recur Fitogeneticos; 1994.

Tubiello FN, Salvatore M, Condor Golec RD, Ferrara A, Rossi S, Biancalani R. Agriculture forestry and other land use emissions by sources and removals by sinks. Rome Italy; 2014 Mar. p. 1111.

Saifullah M, Rabbani MG. Evaluation and characterization of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench.) genotypes. SAARC J Agric. 2009;7(1):91-8.

Gopalan C, Rama Sastri BV, Balasubramanian SC. Nutritive value of Indian foods; 1971.

Dilruba S, Hasanuzzaman M, Karim R, Nahar K. Yield response of okra to different sowing time and application of growth hormones. J Hortic Sci Ornamental Plants. 2009;1:10-4.

Akintoye HA, Adebayo AG, Aina OO. Growth and yield response of okra intercropped with live mulches. Asian J of Agricultural Research. 2011;5(2):146-53. doi: 10.3923/ajar.2011.146.153.

Liu IM, Liou SS, Lan TW, Hsu FL, Cheng JT. Myricetin as the active principle of Abelmoschus moschatus to lower plasma glucose in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Planta Med. 2005 Jul;71(7):617-21. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871266, PMID 16041646.

Kumar R, Patil MB, Patil SR, Paschapur MS. Evaluation of Abelmoschus esculentus mucilage as suspending agent in paracetamol suspension. Int J PharmTech Res. 2009 Jul;1(3):658-65.

Altieri MA. The paradox of cuban agriculture. Mon Rev. 2012 Jan 1;63(8):23-33. doi: 10.14452/MR-063-08-2012-01_3.

Chauhan DV. Vegetable production in India. Ram Prasad; 1968.

Chopra RN, Nayar SL. Glossary of Indian medicinal plants. Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; 1956.

Bourdy G, Walter AJ. Maternity and medicinal plants in Vanuatu. I. The cycle of reproduction. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992 Oct 1;37(3):179-96. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90033-n, PMID 1453707.

Salomon Nekiriai C. Medical knowledge and know-how of Kanak Women. ESK/CORDET, Noumea. New Caledonia; 1995.

Kumar A, Singh A. Ethnobotanical and pharmacological profile of Abelmoschus Manihot L.: a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(2):1-4.

Ishikawa H, Okubo K, Oki T. On the characteristics of tororo-aoi [Hibiscus manihot] mucin as a tackifier Neri. of Japanese handmade paper. Journal of the Japan Wood Research Society (Japan). 1980;26(1).

Christina AJ, Muthumani P. Phytochemical investigation and antilithiatic activity of Abelmoschus moschatus Medikus. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5(1):108-13.

Rao VR, Riley KW, Quek P, Mal B, Zhou M. IPGRI-APO activities on plant genetic resources in the region an overview. Int Sanpgr Proc. 1999;74:1-180.