Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 8, 1-7Review Article

3D PRINTING IN PHARMACEUTICALS: TRANSFORMING DRUG FORMULATION AND PERSONALIZED MEDICINE

PUNEET JOSHI*, ABHIJEET OJHA, ARUN KUMAR SINGH, NAVIN CHANDRA PANT

Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Amrapali University, Haldwani, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Puneet Joshi; *Email: puneetjoc@gmail.com

Received: 05 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 12 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Three-dimensional printing is poised to transform the landscape of pharmaceutical manufacturing by enabling the tailored production of medicines that cater to individual patient requirements. Emphasizing its notable contributions to personalized medicine, this review explores the foundational principles and methods of 3D printing in drug delivery. Key methods, including Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), stereolithography (SLA), and semi-solid extrusion, are evaluated for their benefits and difficulties. The study shows how 3D printing overcomes the bounds of conventional manufacturing techniques, including one-size-fits-all and rigid dosing, thereby enabling the on-demand production of complex dosage forms with customized drug release properties and improved solubility for difficult compounds. Along with the historic FDA clearance of SPRITAM®, the first 3D-printed medicine, practical applications have been demonstrated in the production of pediatric mini-tablets, geriatric polypills, and multi-compartment capsules. Moreover, the study discusses how customized implantable devices, bioprinting, and 3D printing are progressively integrated. Although problems, including material compatibility, process standardization, and legal obstacles, still exist, the rapid development rate promises a future in which 3D printing is essential to pharmaceutical practice. It has great potential to enhance therapeutic results and patient quality of life substantially.

Keywords: Fused deposition modeling, Stereolithography, SLS, One size fits all

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i8.54888 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

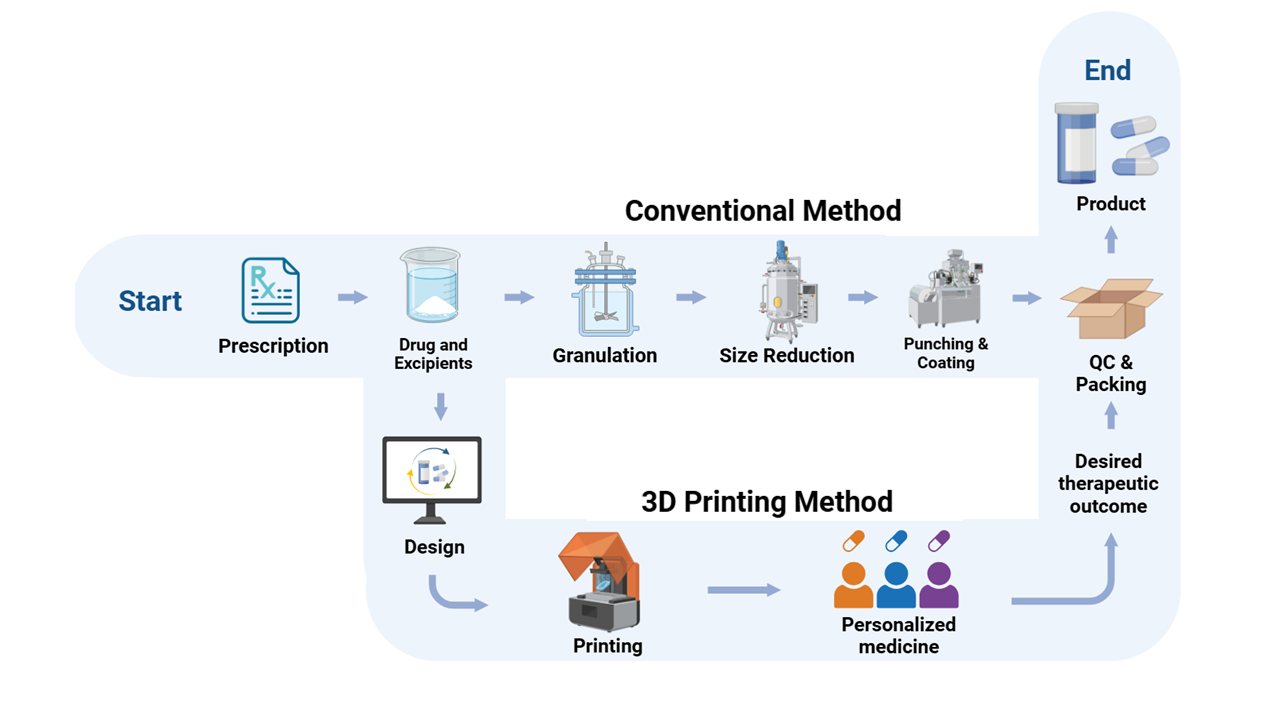

Three-dimensional printing, called additive manufacturing, creates 3D personalized pharmaceutical products layer by layer through computer-aided design (CAD) and precise material deposition. This technology allows the designing and manufacturing of sophisticated drug formulation and delivery systems specific to each patient's needs, departing from traditional 'one size fits all' to customized medications [1]. Notably, data also reveals that 75% of cancer drugs, 70% of Alzheimer's drugs, and 50% of arthritis medications have no significant therapeutic effect, highlighting the limitations of conventional treatments [2]. Conventional manufacturing methods involve multiple steps of granulation, size reduction, and coating and require huge consumption of time and resources.

On the other hand, 3D printing facilitates the direct on-demand production of personalized drugs, streamlining the workflow and thereby improving patient-specific therapeutic outcomes [3]. Another challenge that 3DP can address is the complexity of drug formulations, particularly for poorly soluble drugs. It can solve solubility problems through several mechanisms, including the formation of amorphous solid dispersions (ASD) and increased surface area of the dosage form [4]. The technology allows us to fabricate tablets with varying densities, diffusivities, and internal shapes that are optimized for the drug release profile [5]. It has been recently studied that fusion-assisted 3D printing can produce amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) in situ during the printing process, resulting in a large drug supersaturation. For instance, 3D-printed perforated griseofulvin tablets loaded with the drug showed enhanced supersaturation of up to 293% if perforated, with the effect of increased surface area being helpful in drug dissolution [6].

In healthcare, three-dimensional (3D) printing has now transformed into a technology that has developed into the realms of bioprinting and implants. By this novel approach, the medical equipment can be personalized, providing a basis for the development of patient-specific implants and prostheses, which increase the comfort of patients and improve the surgical results [7]. Defects in bone can be treated through manufacturing scaffolds using 3DP by adding vascular growth factor-loaded hydrogel to calcium phosphate cement [8]. A particular subset of 3D printing that mixes living cells with compatible substances to build tissues and organs has led to significant development in the field of medical therapy. This offers promising solutions for tissue regeneration and cancer treatment [9, 10].

In the pharmaceutical field, the various forms of 3D printing techniques are fused deposition modeling (FDM), stereolithography (SLA), selective laser sintering (SLS), and semi-solid extrusion [11]. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is currently used for designing customized drug release profiles or combinations of multiple active pharmaceutical ingredients for improved bioavailability and patient compliance [12]. For instance, in the case of studies, domperidone floating intragastric tablets have been printed to improve the bioavailability of drugs [13]. Stereolithography (SLA) uses photopolymerization to produce 3D structures like micronized needles to life-sized organs [14]. By allowing for the development of personalized dosage forms, this technology moves pharmacy from a one-size-fits-all approach toward patient-centered medicine. Novel photopolymerizable resin compounds have enabled researchers to make oral dosage forms with sustained drug release profiles [14, 15]. The hot melt extrusion (HME) method utilizes adaptable polymers and has become popular in the 3D printing of drugs, particularly after the FDA gave its approval for SPRITAM®, a rapidly dissolving tablet created through 3D printing [16]. Major developments in 3D printing technology within the pharmaceutical sector have occurred since Spritam® was approved by the FDA in 2015 as the first 3D printed medicine for epilepsy. In February 2021, Triastek received approval from the FDA for its initial 3D-printed medication, T19, for investigational new drug (IND) [1, 17]. This review explores the various 3D printing technologies employed in pharmaceutical manufacturing, their applications, advantages, challenges, and future prospects in advancing patient-centric healthcare. To support this review, a structured literature search was conducted using the Semantic Scholar database. The search focused on the period between 2015 and 2021 and included keywords such as “3D printing,” “personalized medicine,” “pharmaceutical manufacturing,” “Fused Deposition Modeling,” “Selective Laser Sintering,” “Stereolithography,” and “Inkjet Printing.” Studies were selected based on their relevance to pharmaceutical applications of 3D printing, inclusion of experimental or technical details, and focus on customized drug delivery or dosage forms. Ten key studies meeting these criteria were analyzed.

Fig. 1: Comparison of workflow between conventional and 3D printing method

Source: Created by the author using BioRender

Principles of 3D printing in pharmaceutics

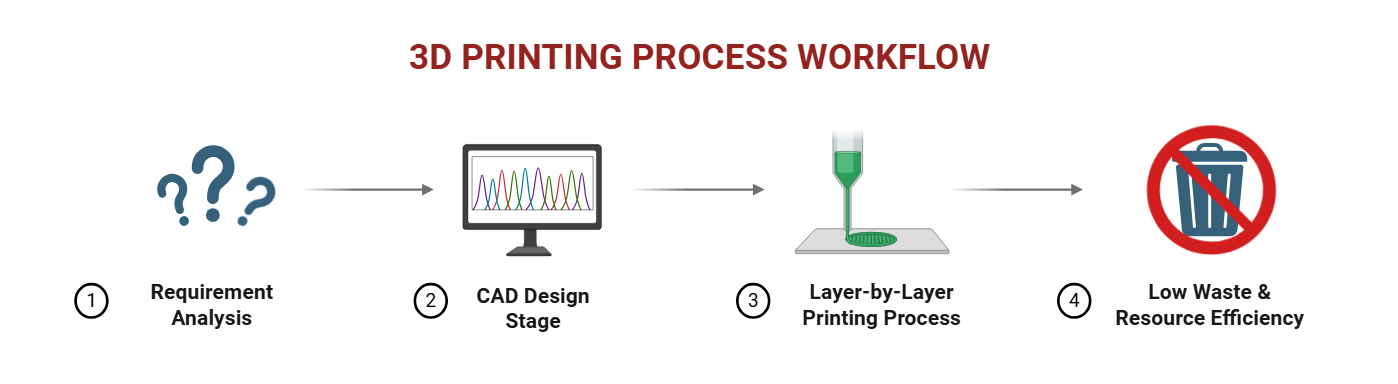

3D printing operates on the principle of layer-by-layer fabrication. The process begins by creating a computer-aided design (CAD) file defining the size, shape, and release profile of the drug, as well as any support parts required, as shown in fig. 2. 3D printing is useful in pharmaceutics since it enables the 3D printer to add material in layers per design of the computer-aided design (CAD), creating complex shapes that standard approaches cannot [18].

This technology’s capability for designing tailored parts as well as minimizing material waste makes it an important technology for sustainable manufacturing approaches [19, 20]. Recent advances in 3D printing have converted the printing process from a static to a dynamic assembly technique, in which full control of the translation, rotation, and scaling of individual layers is provided during fabrication. This allows for patient-specific structures like vascular scaffolds from MRI data and seamless integration of diverse materials, enhancing adaptability and functionality [21].

Fig. 2: 3D printing process workflow

Source: Created by the author using BioRender

MATERIALS AND METHODS

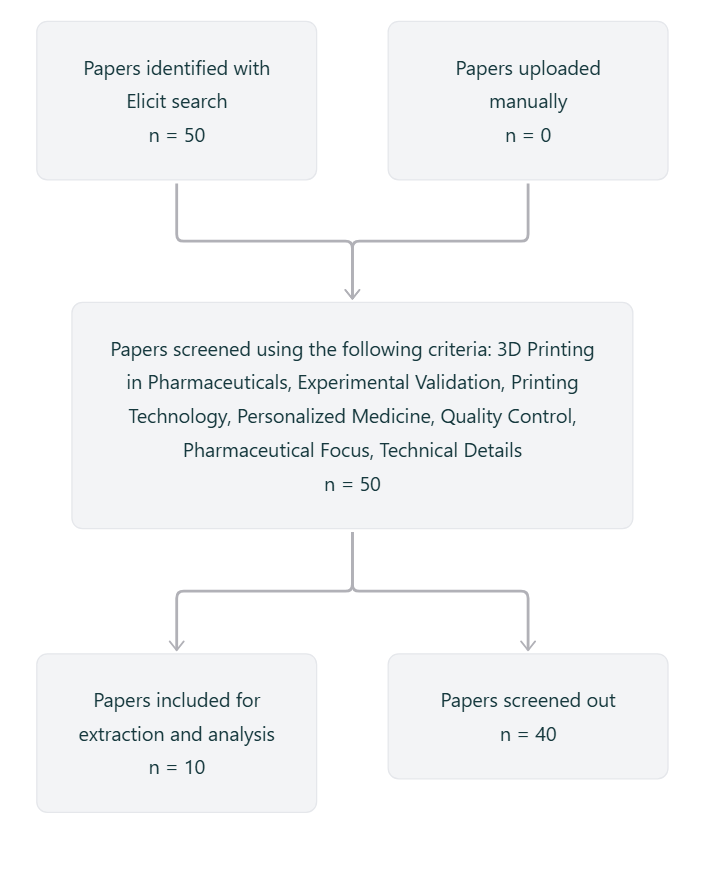

Data were collected through a structured literature search using the Semantic Scholar corpus and the Elicit tool. The search was guided by the research question, “What are the various methods of 3D printing in pharmaceutics that are being used to create personalized medicine and improve upon conventional systems?” Key terms used included “3D printing,” “pharmaceutical manufacturing,” “personalized medicine,” “Fused Deposition Modeling,” “Selective Laser Sintering,” “Inkjet Printing,” and “Binder Jetting.” We applied filters to include studies published from 2015 to 2021, ensuring relevance to current technologies. Papers were screened based on the following criteria: direct relevance to pharmaceutical 3D printing, inclusion of experimental validation or technical discussion, focus on drug formulations (not just medical devices), and applicability to personalized medicine. The 50 most relevant papers were retrieved based on the research question, focusing on studies related to 3D printing technology in pharmaceuticals. Screening criteria included relevance to personalized medicine, specific 3D printing methods (FDM, SLA, and inkjet printing), experimental validation, quality control, and pharmaceutical applications. 10 studies meeting these criteria were included for further analysis, and 40 were excluded for not meeting the criteria. The Elicit flowchart for the systematic review is presented in fig. 3.

Ten studies examine 3D printing for personalized pharmaceutical production [22–31]. Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) appears in eight studies [22, 24–28, 30, 31]. It enables precise dose control, multi-drug incorporation, and complex shapes, but may expose drugs to high temperatures [24, 26, 28]. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), featured in three studies, fabricates solvent‐free dosage forms using FDA-approved materials while noting thermal concerns [23, 27, 31]. Stereolithography (SLA) and inkjet printing, each reported in two studies, offer high resolution and low-temperature processing for tailored release profiles [25, 27, 31]. Binder jetting, covered in one study, allows modular tablet designs with multiple compartments [29].

Fused deposition modeling (FDM)

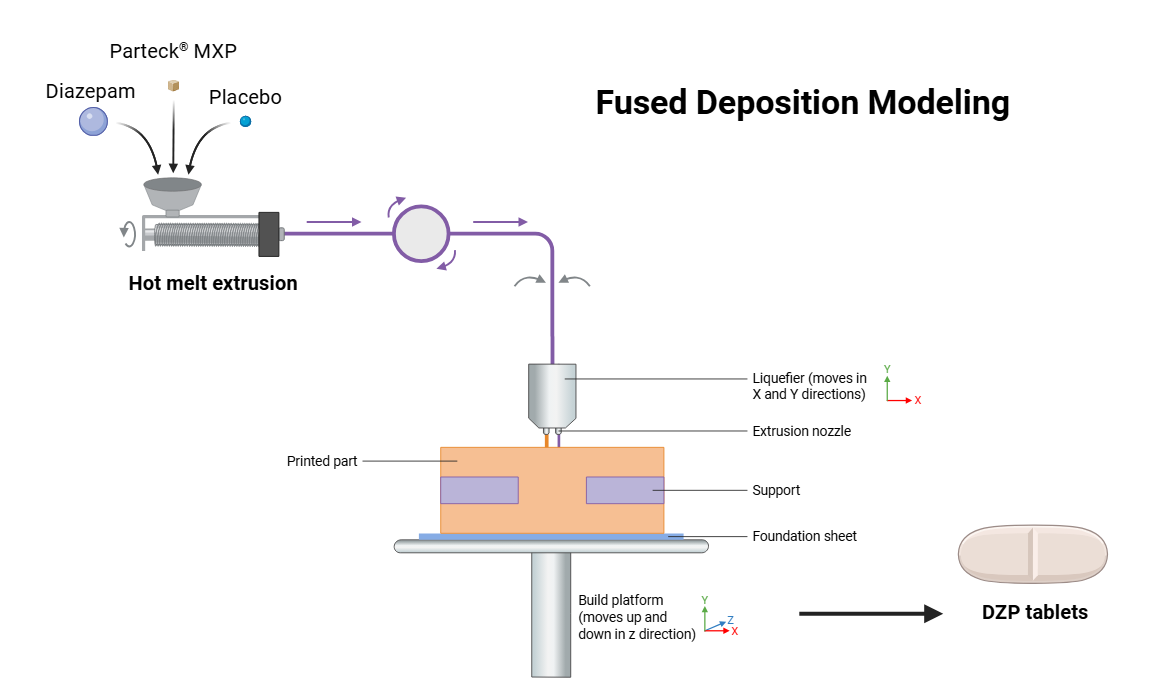

Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) offers high resolution and precise dosage control of various drug release profiles through computer settings in dosage forms [32]. In the process, thermoplastic filaments are extruded layer-by-layer to make 3D objects [33]. Hot melt extrusion (HME) can be used to make pharmaceutical-grade polymer filaments suitable for fused deposition modeling (FDM) for the incorporation of active ingredients and modification of drug release profiles [34]. Ethyl cellulose, polyethylene oxide, and Eudragit® have been used successfully for preparing filaments for immediate or modified release formulations [34].

Fig. 3: ELICIT flow diagram for systematic review

Source: Created by the author

In experimental studies, the fused deposition modeling (FDM) successfully produces Diazepam tablets with placebo, as shown in fig. 4, for managing drug withdrawal, achieving precise drug distribution, good layer adhesion, and conformance to European Pharmacopeia standards [35]. However, there are material properties, processing conditions, and design and specifications associated with equipment that limit the potential of Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) [36]. Challenges that need to be overcome to advance fused deposition modeling (FDM) in pharmaceutical manufacturing include continuous manufacturing of pharmaceutical products with improved controlled release properties and integration of Hot Melt Extrusion (HME) and fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology [37].

Fig. 4: Hot melt extrusion and fused deposition modelling process for diazepam tablet

Source: Created by the author using BioRender

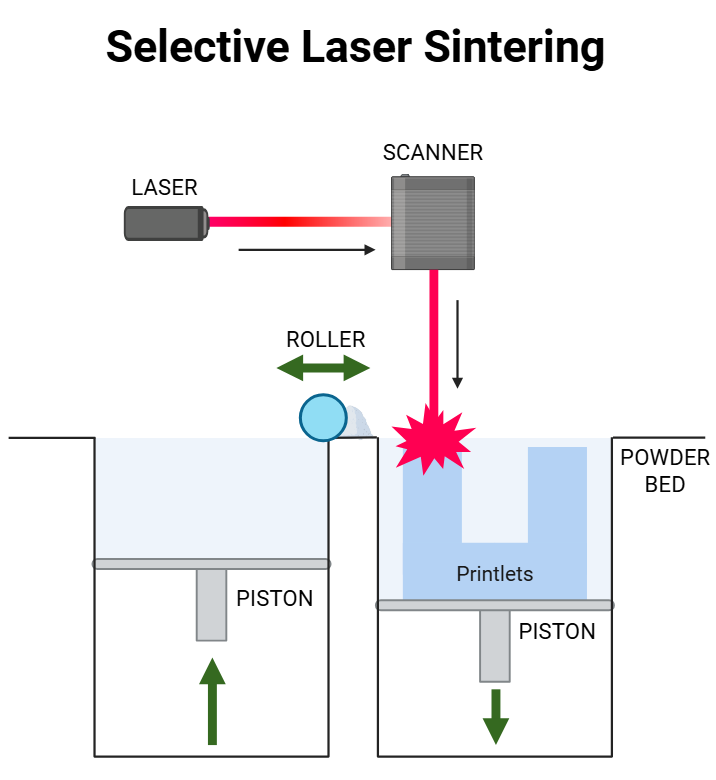

Fig. 5: Selective laser sintering

Source: Created by the author using BioRender

Selective laser sintering (SLS)

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) is one of the emerging 3D printing technologies that has potential applications towards pharmaceuticals. The method involves laser fusion of powdered pharmaceutical materials with a blue diode laser to form complex dosage forms with specific properties, as shown in fig. 5. In SLS, the powder is heated to a temperature just below the melting point of the drug, thereby facilitating the transition of the drug from a crystalline to an amorphous state, which can improve dissolution rate and bioavailability [38, 39]. Advantages of SLS for rapid prototyping are solvent-free processing, minimal post-processing, and porous structures for rapid disintegration [40, 41]. The technique enables production of personalized medicines and amorphous solid dispersions in a single step, such as carvedilol and itraconazole, thereby improving bioavailability [38, 41, 42]. SLS can manufacture drug products with unique engineering properties and high precision [43]. Furthermore, SLS allows the production of tablets with custom release profiles through adjusting the laser scanning speeds, affecting the drug release rate, such as higher speeds increasing the release of theophylline formulations [44].

Table 1: Various drug formulations developed using 3D printing technology

| Approval status | Company | Product name | Application | Technology Used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA Approved | Aprecia Pharmaceuticals | Spritam® (Levetiracetam) | Epilepsy treatment | Binder Jetting (BJ-3DP) | [45] |

| IND Approved | Triastek Inc. | T19 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Melt Extrusion Deposition (MED) | [17] |

| IND Approved | Triastek Inc. | T20 | Cardiovascular disorders | Melt Extrusion Deposition (MED) | [46] |

| IND Approved | Triastek Inc. | T21 | Ulcerative colitis | Melt Extrusion Deposition (MED) | [47] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Indomethacin Tablets | Anti-inflammatory | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | [48] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Acetaminophen Matrix Tablets | Pain relief | Binder Jetting (BJ-3DP) | [49] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Guaifenesin Bilayer Tablets | Cough relief | Extrusion-Based Printing | [50] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Multi-Drug Tablets | Combination therapy | SLA 3D Printing | [51] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Ondansetron Tablets | Anti-emetic | SLS | [52] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Ibuprofen/Paracetamol Chewable | Pediatric use | Extrusion-Based Printing | [53] |

| Research-Based | Academic/Industry Research | Theophylline Delayed-Release | Asthma/COPD treatment | FDM | [54] |

Applications in personalised medicine

Personalized dosage forms

In personalized medicine, 3D printing technology produces creative advances by producing customized drug forms based on age, weight range, genetic profile, and particular medical conditions for pediatric and elderly patient groups [55]. Small tablets containing drugs, such as caffeine and propranolol hydrochloride have been created in pediatrics using fused deposition modeling to enhance precise dosing and tailored release behavior, as shown in fig. 6. 3D printing technology creates customized dosages appropriate for all children [56]. Chewable isoleucine printlets with several flavors and dosages have been created to enhance drug acceptability and therapeutic results in children with metabolic diseases [57].

In elderly patients, 3D printing addresses issues such as polypharmacy and dysphagia (swallowing problems). Focusing on drugs like Donepezil, University Hospital Southampton is an example of running trials to produce 3D-printed medications targeted for older patients with dementia with variations in dose, form, and texture to improve safety and adherence [58]. Additionally, 3D-printed polypills combining multiple drugs into a single tablet have been developed to simplify complex medication regimens common in geriatric care, such as antihypertensive treatments combining diltiazem and propranolol hydrochloride in a floating, sustained-release formulation to increase gastric retention and drug release profiles, 3D-printed polypills combining several medications into a single tablet. Polypills can reduce pill burden and minimize administration mistakes, thereby improving therapeutic results. By changing tablet porosity or geometry, 3D printing also allows control over drug release kinetics, therefore allowing individualized pharmacokinetics tailored to individual patient metabolism and comorbidities [59, 60].

Complex drug release profiles

3D printing allows the production of sophisticated drug release profiles. For example, a controlled-release shell enclosing an immediate-release propranolol HCl tablet was created using extrusion-based 3D printing, so altering its release via shell thickness and polymer ratios [61]. Paracetamol gels used fused deposition modeling (FDM) to show different tablet geometries-cylinder, horn, and reversed horn producing constant, rising, and declining release profiles, as shown in fig. 7, respectively [62]. Stereolithography (SLA) printing of several forms, including cubes, discs, spheres, and toroids, revealed drug release rates relate with surface area-to-volume ratio, hence allowing customized dissolution kinetics [63]. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) "radiator-like" tablet print is another creative design whereby drug release relies on spacing between parallel plates, therefore enabling quick or sustained release. To attain progressive drug release over long durations, 3D printed multi-compartment capsules with single, double, or triple reservoirs have been used [63].

Fig. 6: FDM printed tablets for children

Source: Krause J, Müller L, Sarwinska D, Seidlitz A, Sznitowska M, Weitschies W. 3D Printing of Mini Tablets for Pediatric Use. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Feb 11;14(2):143 [56]

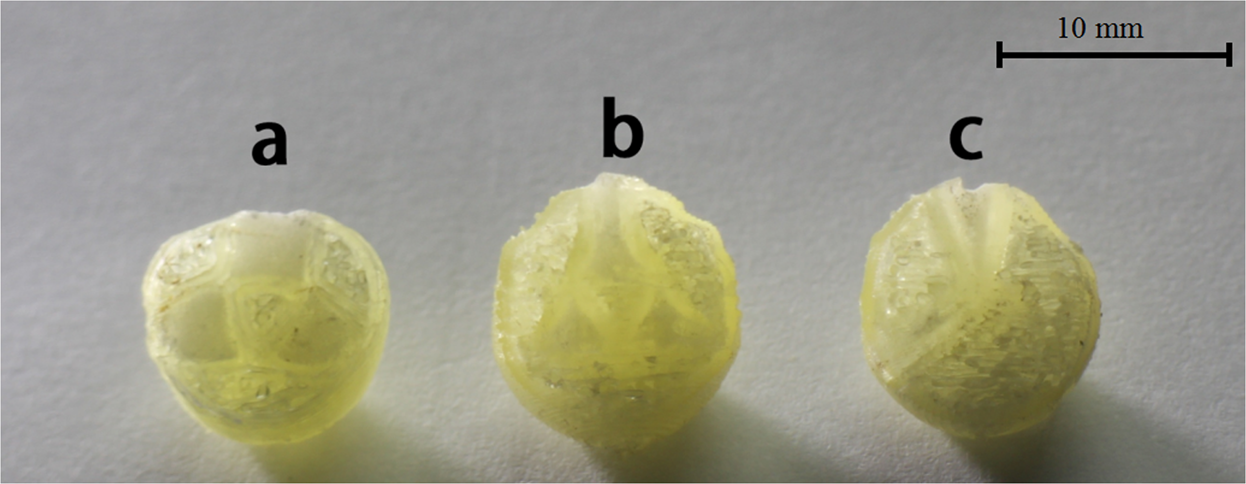

Fig. 7: 3D printed tablets (a) Cylinder model, (b) Horn model, (c) R-Horn model

Source: Xu X, Zhao J, Wang M, Wang L, Yang J. 3D Printed Polyvinyl Alcohol Tablets with Multiple Release Profiles. Sci Rep. 2019 Aug 28;9(1):12487 [62]

RESULTS

This review highlights the transformative effects of 3D printing (3DP) in pharmaceuticals, particularly in relation to personalized medicine. It emphasizes how 3DP allows the production of patient-specific pharmaceutical formulations, thereby solving the constraints of conventional manufacturing, such as rigid dosing, complicated processes, and inefficiencies. The article discusses several 3DP technologies, such as fused deposition modeling (FDM), selective laser sintering (SLS), stereolithography (SLA), and semi-solid extrusion, explaining their ideas, benefits, and medical uses.

CONCLUSION

3D printing is transforming pharmaceutical manufacturing by allowing the creation of unique drug compositions tailored to individual patient needs. This technology enables the production of sophisticated drug release profiles, better solubility of poorly soluble medicines, and patient-friendly dosing forms while overcoming several drawbacks of conventional manufacturing, such as rigid dosing and ineffective workflows. Its use in personalized medicine, which meets the particular needs of pediatric and elderly groups, as well as those with particular genetic profiles or comorbidities, is especially powerful. The approval of 3D-printed medications such as SPRITAM ® by the FDA and continuous clinical studies confirm the clinical and regulatory promise of this technique. Rapid developments in 3D printing technologies point to a hopeful future for patient-centered, on-demand drug production, even though difficulties still exist in material compatibility, process standardization, and regulatory pathways. The future integration of 3D printing into regular pharmaceutical practice is projected based on ongoing research and technological advances, which will enhance therapeutic results and progress the field of precision medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Amrapali University, Haldwani, Uttarakhand, India, for providing the necessary support and academic environment to carry out this work. We express our heartfelt thanks to our parents for their unconditional support and encouragement throughout our academic journeys. Above all, we are deeply thankful to God Almighty for giving us the strength, wisdom, and perseverance to complete this work.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Puneet Joshi conceptualized the review topic, supervised the overall structure and flow of the manuscript, and served as the corresponding author of the manuscript. Abhijeet Ojha conducted the literature search and drafted key sections of the manuscript. Arun Kumar Singh assisted in organizing the data, figures, and references and contributed to the critical review of the content. Navin Chandra Pant helped refine the manuscript and provided academic guidance during the writing and revision process. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Wang S, Chen X, Han X, Hong X, Li X, Zhang H. A review of 3D printing technology in pharmaceutics: technology and applications now and future. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jan 26;15(2):416. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020416, PMID 36839738.

Personalized medicine coalition. The personalized medicine report opportunity challenges and the future. In: Washington, DC: Personalized Medicine Coalition; 2020 Available from: https://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Userfiles/PMC-Corporate/file/PMC_The_Personalized_Medicine_Report_Opportunity_Challenges_and_the_Future.pdf.

Cheng JT, Tan EC, Kang L. Pharmacy 3D printing. Biofabrication. 2024 Oct 24;17(1):012002. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ad837a, PMID 39366411.

Jennotte O, Koch N, Lechanteur A, Evrard B. Three-dimensional printing technology as a promising tool in bioavailability enhancement of poorly water-soluble molecules: a review. Int J Pharm. 2020 Apr 30;580:119200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119200, PMID 32156531.

Yu DG, Zhu LM, Branford White CJ, Yang XL. Three-dimensional printing in pharmaceutics: promises and problems. J Pharm Sci. 2008 Sep;97(9):3666-90. doi: 10.1002/jps.21284, PMID 18257041.

Buyukgoz GG, Kossor CG, Dave RN. Enhanced supersaturation via fusion-assisted amorphization during FDM 3D printing of crystalline poorly soluble drug-loaded filaments. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Nov 4;13(11):1857. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111857, PMID 34834272.

Tripathi S, Mandal SS, Bauri S, Maiti P. 3D bioprinting and its innovative approach for biomedical applications. Med. 2023;4(1):e194. doi: 10.1002/mco2.194, PMID 36582305, PMCID PMC9790048.

Nandi S. 3D printing of pharmaceuticals leading trend in pharmaceutical industry and future perspectives. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2020 Dec 7;13(6):10-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2020.v13i12.39584.

Bg PK, Mehrotra S, Marques SM, Kumar L, Verma R. 3D printing in personalized medicines: a focus on applications of the technology. Mater Today Commun. 2023 Jun;35:105875. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.105875.

Vanaei S, Parizi MS, Vanaei S, Salemizadehparizi F, Vanaei HR. An overview on materials and techniques in 3D bioprinting toward biomedical application. Engineered Regeneration. 2021;2:1-18. doi: 10.1016/j.engreg.2020.12.001.

Singhvi G, Patil S, Girdhar V, Chellappan DK, Gupta G, Dua K. 3D-printing: an emerging and revolutionary technology in pharmaceuticals. Panminerva Med. 2018 Dec;60(4):170-3. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03467-5, PMID 29856179.

Araujo MR, Sa Barreto LL, Gratieri T, Gelfuso GM, Cunha Filho M. The digital pharmacies era: how 3D printing technology using fused deposition modeling can become a reality. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Mar 19;11(3):128. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11030128, PMID 30893842.

Chai X, Chai H, Wang X, Yang J, Li J, Zhao Y. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printed tablets for intragastric floating delivery of domperidone. Sci Rep. 2017 Jun 6;7(1):2829. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03097-x, PMID 28588251.

Lakkala P, Munnangi SR, Bandari S, Repka M. Additive manufacturing technologies with emphasis on stereolithography 3D printing in pharmaceutical and medical applications: a review. Int J Pharm X. 2023 Jan 3;5:100159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2023.100159, PMID 36632068, PMCID PMC9827389.

Healy AV, Fuenmayor E, Doran P, Geever LM, Higginbotham CL, Lyons JG. Additive manufacturing of personalized pharmaceutical dosage forms via stereolithography. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Dec 3;11(12):645. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11120645, PMID 31816898.

Kushwaha S. Application of hot melt extrusion in pharmaceutical 3D printing. J Bioequiv Availab. 2018 Jan 1;10(3):379. doi: 10.4172/0975-0851.1000379.

Zhou Y, Ji M, Wang L, Deng F, Cheng S, Li X. POS1361 a novel oral 3D-printed delayed and extended release tofacitinib (T19) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and related inflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Jun;83 Suppl 1:592. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2024-eular.1022.

Safhi AY. Three-dimensional (3D) printing in cancer therapy and diagnostics: current status and future perspectives. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(6):678. doi: 10.3390/ph15060678, PMID 35745597.

Kantaros A. 3D printing in regenerative medicine: technologies and resources utilized. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan;23(23):14621. doi: 10.3390/ijms232314621, PMID 36498949.

Sinha P, Lahare P, Sahu M, Cimler R, Schnitzer M, Hlubenova J. Concept and evolution in 3D printing for excellence in healthcare. Curr Med Chem. 2025;32(5):831-79. doi: 10.2174/0109298673262300231129102520, PMID 38265395.

Huang J, Ware HO, Hai R, Shao G, Sun C. Conformal geometry and multimaterial additive manufacturing through freeform transformation of building layers. Adv Mater. 2021;33(11):e2005672. doi: 10.1002/adma.202005672, PMID 33533141.

Cailleaux S, Sanchez Ballester NM, Gueche YA, Bataille B, Soulairol I. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) the new asset for the production of tailored medicines. J Control Release. 2021 Feb;330:821-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.056, PMID 33130069.

Charoo NA, Barakh Ali SF, Mohamed EM, Kuttolamadom MA, Ozkan T, Khan MA. Selective laser sintering 3D printing an overview of the technology and pharmaceutical applications. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020 May 13;46(6):869-77. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2020.1764027, PMID 32364418.

Dumpa N, Butreddy A, Wang H, Komanduri N, Bandari S, Repka MA. 3D printing in personalized drug delivery: an overview of hot melt extrusion-based fused deposition modeling. Int J Pharm. 2021 May;600:120501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120501, PMID 33746011.

FG, Velez A. 3D pharming: direct printing of personalized pharmaceutical tablets. Polym Sci. 2016;2(1):100011. doi: 10.4172/2471-9935.100011.

Goyanes A, Wang J, Buanz A, Martinez Pacheco R, Telford R, Gaisford S. 3D printing of medicines: engineering novel oral devices with unique design and drug release characteristics. Mol Pharm. 2015 Oct 16;12(11):4077-84. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00510, PMID 26473653.

Okafor Muo OL, Hassanin H, Kayyali R, ElShaer A. 3D printing of solid oral dosage forms: numerous challenges with unique opportunities. J Pharm Sci. 2020 Dec;109(12):3535-50. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2020.08.029, PMID 32976900.

Pietrzak K, Isreb A, Alhnan MA. A flexible dose dispenser for immediate and extended release 3D printed tablets. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015 Oct;96:380-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.07.027, PMID 26277660.

Rahman Z, Charoo NA, Kuttolamadom M, Asadi A, Khan MA. Printing of personalized medication using binder jetting 3D printer. In: Precision medicine for investigators, practitioners and providers. Elsevier; 2020. p. 473-81. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-819178-1.00046-0.

Sadia M, Sosnicka A, Arafat B, Isreb A, Ahmed W, Kelarakis A. Adaptation of pharmaceutical excipients to FDM 3D printing for the fabrication of patient-tailored immediate release tablets. Int J Pharm. 2016 Nov;513(1-2):659-68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.09.050, PMID 27640246.

Vaz VM, Kumar L. 3D printing as a promising tool in personalized medicine. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2021 Jan;22(1):30. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01905-8.

Glukhova SA, Molchanov VS, Chesnokov YM, Lokshin BV, Kharitonova EP, Philippova OE. Green nanocomposite gels based on binary network of sodium alginate and percolating halloysite clay nanotubes for 3D printing. Carbohydr Polym. 2022 Apr 15;282:119106. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119106, PMID 35123742.

Pund A, Magar M, Ahirrao Y, Chaudhari A, Amritkar A. 3D printing technology: a customized advanced drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022 Aug 7;15(8):23-33. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i8.45136.

Melocchi A, Parietti F, Maroni A, Foppoli A, Gazzaniga A, Zema L. Hot melt extruded filaments based on pharmaceutical grade polymers for 3D printing by fused deposition modeling. Int J Pharm. 2016 Jul 25;509(1-2):255-63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.05.036, PMID 27215535.

Macedo J, Marques R, Vervaet C, Pinto JF. Production of bi-compartmental tablets by FDM 3D printing for the withdrawal of diazepam. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Feb 6;15(2):538. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020538, PMID 36839860, PMCID PMC9960133.

Parulski C, Jennotte O, Lechanteur A, Evrard B. Challenges of fused deposition modeling 3D printing in pharmaceutical applications: where are we now? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Aug;175:113810. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.05.020, PMID 34029646.

Tan DK, Maniruzzaman M, Nokhodchi A. Advanced pharmaceutical applications of hot melt extrusion coupled with fused deposition modelling (FDM) 3D printing for personalised drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2018 Oct 24;10(4):203. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040203, PMID 30356002, PMCID PMC6321644.

Pesic N, Ivkovic B, Barudzija T, Grujic B, Ibric S, Medarevic D. Selective laser sintering 3D printing of carvedilol tablets: enhancing dissolution through amorphization. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Dec 24;17(1):6. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17010006, PMID 39861659, PMCID PMC11768180.

Gueche YA, Sanchez Ballester NM, Cailleaux S, Bataille B, Soulairol I. Selective laser sintering (SLS) a new chapter in the production of solid oral forms (SOFs) by 3D printing. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Aug 6;13(8):1212. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13081212, PMID 34452173, PMCID PMC8399326.

Charoo NA, Barakh Ali SF, Mohamed EM, Kuttolamadom MA, Ozkan T, Khan MA. Selective laser sintering 3D printing an overview of the technology and pharmaceutical applications. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020 Jun;46(6):869-77. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2020.1764027, PMID 32364418.

Balasankar A, Anbazhakan K, Arul V, Mutharaian VN, Sriram G, Aruchamy K. Recent advances in the production of pharmaceuticals using selective laser sintering. Biomimetics (Basel). 2023 Jul 27;8(4):330. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics8040330, PMID 37622935.

Trenfield SJ, Januskaite P, Goyanes A, Wilsdon D, Rowland M, Gaisford S. Prediction of solid state form of SLS 3D printed medicines using NIR and Raman spectroscopy. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Mar 8;14(3):589. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14030589, PMID 35335965, PMCID PMC8949593.

Awad A, Fina F, Goyanes A, Gaisford S, Basit AW. 3D printing: principles and pharmaceutical applications of selective laser sintering. Int J Pharm. 2020 Aug 30;586:119594. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119594, PMID 32622811.

Trenfield SJ, Xu X, Goyanes A, Rowland M, Wilsdon D, Gaisford S. Releasing fast and slow: non-destructive prediction of density and drug release from SLS 3D printed tablets using NIR spectroscopy. Int J Pharm X. 2023 Dec;5:100148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2022.100148, PMID 36590827.

Reddy CV, VB, Venkatesh MP, Pramod Kumar TM. First FDA approved 3D printed drug paved new path for increased precision in patient care. ACCTRA. 2020;7(2):93-103. doi: 10.2174/2213476X07666191226145027.

Alqahtani AA, Ahmed MM, Mohammed AA, Ahmad J. 3D printed pharmaceutical systems for personalized treatment in metabolic syndrome. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Apr 5;15(4):1152. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15041152, PMID 37111638, PMCID PMC10144629.

Wojtylko M, Lamprou DA, Froelich A, Kuczko W, Wichniarek R, Osmalek T. 3D-printed solid oral dosage forms for mental and neurological disorders: recent advances and future perspectives. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2024 Nov;21(11):1523-41. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2023.2292692, PMID 38078427.

Huang L, Yang W, Bu Y, Yu M, Xu M, Guo J. Patient-focused programable release indomethacin tablets prepared via conjugation of hot melt extrusion (HME) and fused depositional modeling (FDM)-3D printing technologies. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024 Aug 1;97:105797. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105797.

Gaurkhede SG, Osipitan OO, Dromgoole G, Spencer SA, Pasqua AJ, Deng J. 3D printing and dissolution testing of novel capsule shells for use in delivering acetaminophen. J Pharm Sci. 2021 Dec;110(12):3829-37. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2021.08.030, PMID 34469748.

Khaled SA, Burley JC, Alexander MR, Roberts CJ. Desktop 3D printing of controlled release pharmaceutical bilayer tablets. Int J Pharm. 2014 Jan 30;461(1-2):105-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.021, PMID 24280018.

Khaled SA, Burley JC, Alexander MR, Yang J, Roberts CJ. 3D printing of tablets containing multiple drugs with defined release profiles. Int J Pharm. 2015 Oct 30;494(2):643-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.07.067, PMID 26235921.

Allahham N, Fina F, Marcuta C, Kraschew L, Mohr W, Gaisford S. Selective laser sintering 3D printing of orally disintegrating Printlets containing ondansetron. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Jan 30;12(2):110. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020110, PMID 32019101, PMCID PMC7076455.

Karavasili C, Zgouro P, Manousi N, Lazaridou A, Zacharis CK, Bouropoulos N. Cereal-based 3D printed dosage forms for drug administration during breakfast in pediatric patients within a hospital setting. J Pharm Sci. 2022 Sep;111(9):2562-70. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2022.04.013, PMID 35469835.

Okwuosa TC, Pereira BC, Arafat B, Cieszynska M, Isreb A, Alhnan MA. Fabricating a shell core delayed release tablet using dual FDM 3D printing for patient-centred therapy. Pharm Res. 2017 Feb;34(2):427-37. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-2073-3, PMID 27943014.

Palekar S, Nukala PK, Mishra SM, Kipping T, Patel K. Application of 3D printing technology and quality by design approach for development of age-appropriate pediatric formulation of baclofen. Int J Pharm. 2019 Feb 10;556:106-16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.062, PMID 30513398.

Krause J, Muller L, Sarwinska D, Seidlitz A, Sznitowska M, Weitschies W. 3D printing of mini tablets for pediatric use. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Feb 11;14(2):143. doi: 10.3390/ph14020143, PMID 33670158, PMCID PMC7916857.

Ianno V, Vurpillot S, Prillieux S, Espeau P. Pediatric formulations developed by extrusion-based 3D printing: from past discoveries to future prospects. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Mar 22;16(4):441. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16040441, PMID 38675103, PMCID PMC11054634.

Monou PK, Andriotis EG, Saropoulou E, Tzimtzimis E, Tzetzis D, Komis G. Fabrication of hybrid coated microneedles with donepezil utilizing digital light processing and semisolid extrusion printing for the management of alzheimers disease. Mol Pharm. 2024 Sep 2;21(9):4450-64. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.4c00377, PMID 39163171, PMCID PMC11372831.

Zgouro P, Katsamenis OL, Moschakis T, Eleftheriadis GK, Kyriakidis AS, Chachlioutaki K. A floating 3D printed polypill formulation for the coadministration and sustained release of antihypertensive drugs. Int J Pharm. 2024 Apr 25;655:124058. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124058, PMID 38552754.

Pereira BC, Isreb A, Isreb M, Forbes RT, Oga EF, Alhnan MA. Additive manufacturing of a point of care polypill: fabrication of concept capsules of complex geometry with bespoke release against cardiovascular disease. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(13):e2000236. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202000236, PMID 32510859.

Algahtani MS, Mohammed AA, Ahmad J, Saleh E. Development of a 3D printed coating shell to control the drug release of encapsulated immediate release tablets. Polymers (Basel). 2020 Jun 22;12(6):1395. doi: 10.3390/polym12061395, PMID 32580349, PMCID PMC7362262.

Xu X, Zhao J, Wang M, Wang L, Yang J. Author correction: 3D printed polyvinyl alcohol tablets with multiple release profiles. Sci RepSci Rep. 2020;10(1):2394. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59303-w, PMID 32024930.

Potpara Z. The role of 3D printing in the development of dosage forms with tailored drug release. Farmacia. 2024;72(6):1251-60. doi: 10.31925/farmacia.2024.6.3.