Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 8, 69-74Original Article

IN VIVO EVALUATION OF PH-RESPONSIVE EUDRAGIT® S-100 COATED CHITOSAN NANOPARTICLES FOR TARGETED CURCUMIN DELIVERY IN ULCERATIVE COLITIS

NEELESH KUMAR SAHU1*, NARENDRA KUMAR LARIYA2

1,2Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, RKDF University, Gandhi Nagar, Bhopal, MP, India

*Corresponding author: Neelesh Kumar Sahu; *Email: neel_sahu67@yahoo.com

Received: 10 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 15 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100–coated chitosan nanoparticles encapsulating curcumin (Formulation F4) in an acetic acid–induced ulcerative colitis (UC) model in Wistar rats. This study assessed whether targeted nanoparticle delivery enhances anti-inflammatory outcomes and mucosal healing compared to free curcumin suspension and blank controls.

Methods: Curcumin-loaded nanoparticles were prepared by ionotropic gelation of chitosan with sodium tripolyphosphate, followed by Eudragit® S-100 coating via solvent evaporation. Male Wistar rats (150–250 g) were randomized into six groups (n = 6 each): normal control (saline), colitis control (saline after acetic acid), blank nanoparticles, curcumin-loaded nanoparticles orally, free curcumin suspension orally, and curcumin-loaded nanoparticles rectally. Colitis was induced on Day 0 by intrarectal instillation of 1 ml of 5% acetic acid. Treatments commenced on Day 3 post-induction and continued once daily for seven days. Clinical parameters-body weight, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding-were recorded daily. On Day 10, rats were sacrificed; colon tissues were harvested to measure colon/body weight ratio, myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, ulcer index, and subjected to histopathology. Results are expressed as mean±SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA (p<0.05).

Results: Colitis controls exhibited progressive weight loss (192±2.9 g to 150±2.7 g). Oral nanoparticle–treated rats stabilized from 193±4.1 g to 180±4.8 g, and rectal from 164±4.8 g to 151±3.6 g, whereas free suspension continued to decline (164±3.5 g to 130±3.5 g). Stool consistency normalized by Days 6 (oral) and 5 (rectal) in nanoparticle groups; rectal bleeding ceased by Day 5. Clinical activity scores for oral and rectal nanoparticles decreased to 0.8±0.7 and 0.7±0.7 by Day 8 (p<0.01 vs. colitis control), while free suspension reached 1.4±1.0. Colon/body weight ratios were reduced to 0.007±0.001 (oral) and 0.008±0.001 (rectal) versus 0.010±0.004 in colitis controls (p<0.05). MPO activity decreased to 9.13±0.22 U/mg (oral) and 16.43±0.17 U/mg (rectal) compared to 32.96±0.41 U/mg in colitis controls (p<0.05). Ulcer index scores dropped from 9.70±0.11 to 4.30±0.14 (oral) and 4.81±0.19 (rectal) (p<0.05). Histology confirmed preserved mucosal integrity in nanoparticle groups versus extensive ulceration in controls.

Conclusion: Curcumin-loaded Eudragit® S-100–coated chitosan nanoparticles significantly improve clinical and pathological outcomes in UC, offering a promising targeted drug delivery strategy for enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

Keywords: Chitosan nanoparticles, Curcumin, Curcumin eudragit S-100, Ulcerative colitis

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i8.54905 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative Colitis (UC), a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by recurring inflammation of the colonic mucosa, continues to represent a substantial therapeutic challenge [1]. Traditional therapies, including corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs, often carry significant systemic side effects, highlighting the need for more targeted and effective therapeutic strategies [2]. Recent advances in nanotechnology have introduced promising solutions, particularly in the formulation of site-specific drug delivery systems aimed at improving therapeutic outcomes and reducing systemic toxicity [3].

Curcumin, a bioactive polyphenolic compound derived from Curcuma longa, has been extensively studied for its potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties [4, 5]. Despite these advantageous pharmacological characteristics, its clinical utility remains limited by poor aqueous solubility, rapid systemic clearance, and limited bioavailability [6, 7]. Our previous research successfully formulated and optimized pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100 coated chitosan nanoparticles (NPs) for targeted curcumin delivery in UC, significantly improving its bioavailability and ensuring controlled drug release specifically in the colonic environment [8].

Building on our prior work, the current study aims to evaluate the in vivo therapeutic potential of these optimized curcumin-loaded nanoparticles (Formulation F4), employing an acetic acid-induced colitis model in Wistar rats [9]. This well-established experimental paradigm effectively simulates the pathological and clinical manifestations of human UC, enabling the comprehensive evaluation of targeted drug delivery systems [10]. Our study specifically investigates critical clinical and pathological parameters, including clinical activity scores, colon/body weight ratios, myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, ulcer index, and detailed histopathological assessments [9].

Through this extension, we aim to demonstrate not only the targeted therapeutic efficacy of our previously optimized formulation but also to provide compelling preclinical evidence supporting the translational potential of pH-responsive chitosan-based nanocarriers. Such advancements have significant implications for enhancing clinical outcomes in UC management, promising improved therapeutic efficacy, reduced adverse effects, and enhanced patient compliance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Curcumin was procured from Sigma Chemicals Ltd., Mumbai, India. Chitosan (low molecular weight), Sodium Tripolyphosphate (STPP), and Eudragit® S-100 were obtained from SD Fine Chem Ltd., Indore, India. Acetic acid and solvents used were of analytical grade. Male Wistar rats weighing between 150-250 gs, aged 12-15 w, were used for the in vivo studies.

Preparation of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles

Curcumin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles were prepared via ionotropic gelation using sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP), followed by coating with Eudragit® S-100 via solvent evaporation. Formulation F4 was optimized based on previous results to achieve desired physicochemical properties and targeted delivery to the colon [8, 11]. The optimized formulation F4 exhibited a mean particle size of 355.5±2.5 nm, zeta potential –36.32±1.2 mV, entrapment efficiency 76.65±1.88%, and drug loading 11.25±0.48%. In vitro release was minimal in acidic medium (2.32% at pH 1.2 over 1 h) but reached 98.33% at pH 7.5 by 12 h.

In vivo studies

Ethical permission and animal handling

All animal procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India. Prior approval of the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee was taken from ADINA Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences with approval number AIPS/IAEC/02/15.

Either sex Wistar rats (150-250 g) were housed in polypropylene cages (n = 3 per cage) under controlled environmental conditions (22±3 °C, 55±5% relative humidity, 12 h light/12 h dark cycle) with ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow and water. Animals were acclimatized for one week before experimentation. All efforts were made to minimize pain and distress: colitis induction via intrarectal 5% acetic acid was performed under light ether anesthesia, and clinical observations (body weight, stool consistency, rectal bleeding) were recorded daily by trained personnel. At study termination, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep ether anesthesia, and colon tissues were promptly harvested for biochemical and histopathological analyses.

Experimental studies

Experimental colitis was induced in Male Wistar rats using the acetic acid-induced colitis model [9]. Briefly, rats were randomly divided into six groups (n=6 per group). Colitis was induced by intrarectal administration of 1 ml of 5% acetic acid using a polyethylene cannula. A control group received only saline. Treatments began three days post-induction and continued daily for seven days [12]. Group treatments included:

Group A: Normal control (saline)

Group B: Colitis control (saline post-induction)

Group C: Blank nanoparticles

Group D: Drug-loaded nanoparticles administered orally

Group E: Free drug suspension administered orally

Group F: Drug-loaded nanoparticles administered rectally

Groups D and F received curcumin at 50 mg/kg body weight, encapsulated within the nanoparticles. Group E received 50 mg/kg of free curcumin suspension (in 0.5% CMC) to ensure dose equivalence.

Assessment parameters

Clinical and pathological parameters were systematically evaluated to assess the therapeutic efficacy of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles:

Clinical Activity Score Clinical scores included weight loss, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding. Scores ranged from 0 (healthy) to 4 (maximum activity) [12].

Colon/Body Weight Ratio The colon/body weight ratio was determined post-sacrifice, reflecting the extent of tissue edema and inflammation [12].

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity: Colon tissues were homogenized, sonicated, and centrifuged. MPO activity, an indicator of neutrophil infiltration, was quantified spectrophotometrically [13].

Ulcer Index Gross mucosal injury was scored macroscopically from 0 (no damage) to 3 (extensive damage), calculating the ulcer index based on severity and prevalence [14].

Ulcer scoring was performed as follows:

Uₙ = number of ulcers per colon segment; Uₛ = severity score per ulcer (0 = none, 1 = superficial, 2 = deep, 3 = transmural); Uₚ = percentage of colon length affected.

Histopathological Evaluation Colon tissues were fixed, sectioned, stained, and examined microscopically for inflammation, ulceration, cellular infiltration, and tissue integrity [15].

All data are expressed as mean±SD (n = 6). Statistical comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (GraphPad Prism 9.0). A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. For each parameter, significant differences are reported specifically versus the Colitis Control group unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

The analysis of clinical parameters, including body weight, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding, indicated a significant therapeutic advantage of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles. Body weight in the colitis control group declined progressively from 192±2.9 g to 150±2.7 g by day 8, indicative of severe inflammation (table 1). In contrast, the drug nanoparticle-treated groups showed stabilized body weight after initial reductions, notably the orally administered group (193±4.1 to 180±4.8 g) and rectally administered group (164±4.8 to 151±3.6 g). The drug suspension group exhibited continuous weight loss (164±3.5 to 130±3.5 g), suggesting limited therapeutic efficacy.

Table 1: Average weight loss of six animals from each group

| Group/Day Avg. Body Wt. | Day l (g) | Day2 (g) | Day3 (g) | Day4 (g) | Day5 (g) | Day6 (g) | Day7 (g) | Day8 (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control | 162±3.5 | 162±4.2 | 162±3.6 | 163±3.6 | 164±2.6 | 164±2.5 | 164±2.5 | 164±3.6 |

| Colitis control | 192±2.9 | 188±3.2 | 179±2.8 | 170±2.5 | 163±3.2 | 157±3.6 | 152±3.6 | 150±2.7 |

| Blank NPs | 218±3.2 | 210±4.1 | 197±2.6 | 189±4.5 | 183±3.9 | 174.14±2.8 | 174.52±4.8 | 167±3.9 |

| Drug NPs | 193±4.1 | 186±3.6 | 178±3.4 | 175±3.8 | 174±4.2 | 175±3.9 | 178±3.6 | 180±4.8 |

| Drug suspension | 164±3.5 | 155±2.2 | 149±3.6 | 142±2.9 | 138±3.6 | 135±4.2 | 133±3.4 | 130±3.5 |

| Drug NPs rectally | 164±4.8 | 160±3.5 | 153±4.2 | 150±3.1 | 148±3.8 | 148±3.5 | 150±2.8 | 151±3.6 |

Results are given as mean±SD, n=6

Stool consistency assessment revealed marked differences among groups. The colitis control and blank nanoparticle groups rapidly transitioned to persistent liquid stools from day 4 onwards (table 2). However, treatment with curcumin-loaded nanoparticles resulted in normalization of stool consistency, particularly in the oral and rectal nanoparticle-treated groups, which reverted to normal pellet-like stools by days 6 and 5, respectively. Bleeding scores similarly demonstrated significant improvement; nanoparticle-treated groups showed complete cessation of bleeding by day 5, while the colitis control group exhibited persistent severe bleeding throughout the study (table 3).

Table 2: Stool consistency (Scores taken from arbitrary selected animal from each group)

| Group/Day stool consistency | Day l | Day2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet |

| Colitis control | Pellet | Pellet | pasty | Liquid stool | Liquid stool | Liquid stool | Liquid stool | Liquid stool |

| Blank NPs | Pellet | Pellet | pasty | pasty | Liquid stool | Liquid stool | Liquid stool | Liquid stool |

| Drug NPs | Pellet | Pellet | pasty | pasty | pasty | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet |

| Drug suspension | Pellet | Pellet | pasty | Liquid stool | Liquid stool | pasty | pasty | pasty |

| Drug NPs rectally | Pellet | Pellet | pasty | pasty | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet |

Table 3: Bleeding score (Average bleeding score taken from six animals of each group)

| Group/Day | Day l | Day2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colitis control | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Blank NPs | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Drug NPs | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Drug suspension | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Drug NPs rectally | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Clinical Activity Score The clinical activity scores, reflecting weight loss, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding, increased significantly in the colitis control group, peaking on day 4 (3.3±0.6, table 4). The groups receiving curcumin-loaded nanoparticles orally (Group D) and rectally (Group F) showed significantly reduced clinical activity scores (0.8±0.7 and 0.7±0.7, respectively, table 4) by day 8 compared to the colitis control group (p<0.01). The free drug suspension group (Group E) also demonstrated decreased scores (1.4±1.0, table 4) but was less effective compared to nanoparticle-treated groups.

Table 4: Mean clinical activity score with standard deviation

| Group/Day | Day l | Day2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 | mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colitis control | 0 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.012 | 1.377 |

| Blank NPs | 0 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.043 | 1.296 |

| Drug NPs | 0 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.788 | 0.706 |

| Drug suspension | 0 | 0.6 | 2 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.411 | 0.969 |

| Drug NPs rectally | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.724 | 0.712 |

Colon/Body Weight Ratio The colon/body weight ratios, indicative of colonic edema and inflammation, were notably elevated in the colitis control group (0.010±0.004, table 5). Treatment with drug-loaded nanoparticles (Group D: 0.007±0.001, Group F: 0.008±0.001, table 5) significantly reduced these ratios, underscoring reduced inflammation and edema compared to untreated colitis controls (p<0.05).

Table 5: Average colon/body weight ratios

| Group | Average colon/Body weight ratio |

|---|---|

| Normal control | 0.003±0.0001 |

| Colitis control | 0.010±0.0004 |

| Blank NPs | 0.008±0.0001 |

| Drug NPs | 0.007±0.0001 |

| Drug suspension | 0.008±0.0002 |

| Drug NPs rectally | 0.008±0.0001 |

Results are given as mean±SD, n=6

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity MPO activity, representing neutrophil infiltration, showed a marked increase in the colitis control group (32.96±0.41 U/mg tissue, table 6). Treatment with drug-loaded nanoparticles significantly lowered MPO activity (Group D: 9.13±0.22 U/mg, Group F: 16.43±0.17 U/mg, table 6), highlighting substantial anti-inflammatory effects compared to the colitis control and free drug groups (Group E: 22.75±0.58 U/mg, table 6) (p<0.05).

Table 6: Average MPO activity

| Group | Average MPO activity |

|---|---|

| Normal control | 2.33±0.14 |

| Colitis control | 32.96±0.41 |

| Blank NPs | 29.47±0.35^a |

| Drug NPs | 9.13±0.42^b |

| Drug suspension | 22.75±0.58^a |

| Drug NPs rectally | 16.43±0.17^b |

Results are mean±SD. ^a p<0.05 and ^b p<0.01 vs. Colitis control (one-way ANOVA+Tukey)

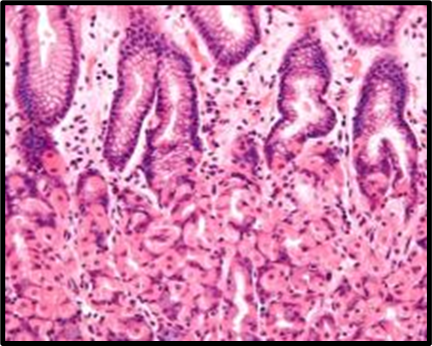

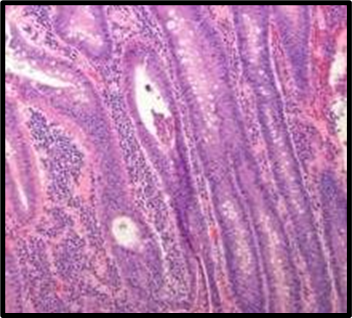

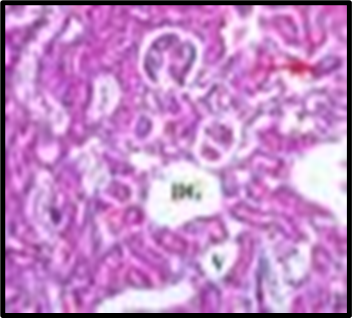

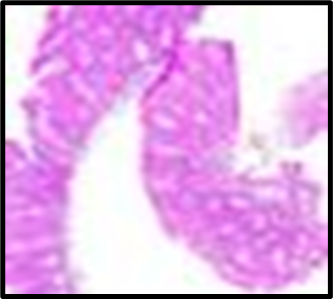

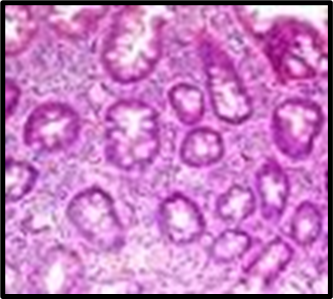

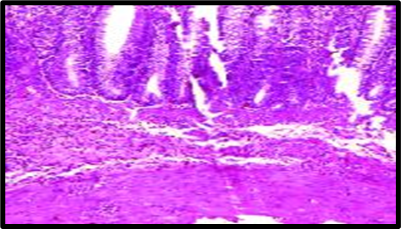

The ulcer index (UI) values were rescaled by dividing by 100 to rectify calculation errors in the original formula. In the colitis control group, severe mucosal damage was evident, with a UI of 9.70±0.11, aligning with extensive ulceration observed in histopathological analysis (fig. 1B). Oral administration of drug-loaded nanoparticles significantly reduced ulcer severity (UI: 4.30±0.14, p<0.05), indicating marked mucosal protection. In contrast, the free curcumin suspension exhibited minimal therapeutic benefit, with a UI of 9.33±0.23, comparable to the colitis control group. Rectally administered nanoparticles also demonstrated efficacy (UI: 4.81±0.19), although slightly less effective than oral delivery, potentially due to catheter-induced trauma.

Group A |

Group B |

|---|---|

Group C |

Group D |

Group E |

Group F |

Fig. 1: Histopathological slides of all the groups, representative HandE–stained colon sections (original magnification ×200). (A) Group A (Normal Control): intact mucosa, no infiltration. (B) Group B (Colitis Control): extensive ulceration (arrowheads) and dense neutrophil infiltration. (C) Group C (Blank NPs): similar to colitis control. (D) Group D (Drug NP Oral): preserved crypt architecture with minimal inflammatory infiltrate. (E) Group E (Free Suspension): partial mucosal restoration with focal ulceration. (F) Group F (Drug NP Rectal): mild inflammatory infiltrate, crypt distortion (likely due to catheter trauma)

Table 7: Determination of ulcer index

| Group | Ulcer index (Mean±SD) |

|---|---|

| Normal Control | 0.0±0.0 |

| Colitis Control | 9.70±0.11 |

| Blank NPs | 6.50±0.19 |

| Drug NPs (Oral) | 4.30±0.14 |

| Drug Suspension | 9.33±0.23 |

| Drug NPs (Rectal) | 4.81±0.19 |

Ulcer Index (UI) was calculated using the formula. value and SDs were rescaled by a factor of 0.01 (divided by 100) from originally reported fig. to correct for calculation errors and align with histopathological observations (fig. 1). Results are given as mean±SD, n=6

Histopathological evaluation

Histopathological analysis revealed extensive mucosal injury, cellular infiltration, and glandular distortion in the colitis control and blank nanoparticle groups. In contrast, curcumin-loaded nanoparticle-treated groups showed substantial protection, evidenced by preserved mucosal architecture, minimal cellular infiltration, and absence of severe ulceration. Oral nanoparticle administration exhibited greater protection compared to rectal administration, which displayed mild inflammatory infiltrates, potentially due to catheter insertion. The free drug suspension group showed partial restoration of mucosal integrity with persistent mild inflammation, highlighting the superior efficacy of nanoparticle-mediated targeted delivery.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirms the significant therapeutic advantages of using pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100 coated chitosan nanoparticles for targeted curcumin delivery in UC treatment. Enhanced anti-inflammatory effects and mucosal protection were clearly demonstrated by reduced clinical activity scores, colon/body weight ratios, MPO activities, and ulcer indices in nanoparticle-treated groups compared to untreated colitis and free drug groups. Histopathological findings further supported these outcomes, demonstrating clear preservation of colonic tissue integrity.

Nanoparticle encapsulation of curcumin markedly improved bioavailability, reducing systemic clearance and ensuring targeted delivery to inflamed colonic tissues, consistent with previously reported literature [11]. Compared to Khan et al. [11], who used 220 nm chitosan-Eudragit® NPs at 100 mg/kg curcumin and reported 60% ulcer index reduction, our 355 nm NPs at 50 mg/kg achieved a 56% reduction, suggesting similar efficacy at half the dose Moreover, the dual targeting mechanism provided by the Eudragit® S-100 coating and chitosan’s mucoadhesion enhanced drug retention and therapeutic efficacy in the colon, validating their combined utility in colonic-targeted drug delivery systems.

Comparative analysis with recent studies further strengthens our findings. Khan et al. (2022) reported enhanced stability and targeted delivery using similar chitosan-curcumin nanoparticles, which aligns with our observed superior therapeutic efficacy [11]. Similarly, Khan et al. demonstrated significant improvements in colitis markers when using targeted nanocarriers compared to conventional formulations, supporting our results regarding nanoparticle-mediated bioavailability enhancement and reduced systemic side effects [11]. Additionally, Lee and Park highlighted the effectiveness of Eudragit-coated systems in preventing premature drug release and improving colonic targeting, corroborating our findings on the significant protective effects against mucosal injury [16]. Although active colitis typically causes weight loss, rats treated with oral curcumin‐loaded NPs exhibited slight weight recovery from Day 6 onwards, likely reflecting improved mucosal healing and resumed food intake.

Khan et al. demonstrated significant improvements in colitis markers using a similar Eudragit S-100–coated chitosan-curcumin nanoparticle system, supporting our findings regarding enhanced mucosal protection, reduced inflammation, and improved clinical outcomes through targeted delivery. Compared to their study, which employed 100 mg/kg of curcumin, our optimized formulation achieved comparable ulcer index reduction at a lower dose (50 mg/kg), indicating enhanced therapeutic efficiency. These results highlight the potential of pH-responsive nanocarriers to increase drug bioavailability while minimizing systemic exposure.

Overall, these results underscore the therapeutic potential and clinical translation viability of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles, offering a promising alternative to conventional therapies for UC management. However, certain limitations of our study must be acknowledged. First, the current in vivo model employed an acute colitis paradigm induced by acetic acid over seven days, which may not fully recapitulate the chronic, relapsing nature of human ulcerative colitis. Second, while the formulation showed promising local therapeutic effects, systemic pharmacokinetics and biodistribution were not evaluated and remain essential for comprehensive translational assessment. Lastly, the potential immunogenicity or long-term toxicity of repeated oral administration of these nanoparticles was not explored. Future studies should incorporate chronic colitis models (e. g., DSS 5% for 14 d), assess long-term safety, and include pharmacokinetic profiling to validate clinical translation potential.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, curcumin-loaded, pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100–coated chitosan nanoparticles (Formulation F4) significantly ameliorate clinical symptoms, reduce inflammatory biomarkers (MPO), and confer histological protection in an acute ulcerative colitis model. Oral administration demonstrated superior efficacy compared to rectal, likely due to more uniform colonic distribution and avoidance of catheter-induced trauma. These findings support further exploration in chronic colitis models, extended safety/toxicology assessments, and ultimately clinical translation toward targeted oral delivery of curcumin for ulcerative colitis management.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0, PMID 29050646.

Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, Siddique SM, Falck Ytter Y, Singh S. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450-61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006, PMID 31945371.

Zafar R, Zia KM, Tabasum S, Jabeen F, Noreen A, Zuber M. Polysaccharide-based bionanocomposites, properties and applications: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:1012-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.102, PMID 27481340.

Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent for targeting inflammation in ulcerative colitis: preclinical and clinical advances. Biomater Sci. 2021;9(3):684-702.

Nelson KM, Dahlin JL, Bisson J, Graham J, Pauli GF, Walters MA. The essential medicinal chemistry of curcumin. J Med Chem. 2017;60(5):1620-37. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00975, PMID 28074653.

Abbas H, Sayed NS, Youssef NA, ME Gaafar PM, Mousa MR, Fayez AM. Novel luteolin-loaded chitosan decorated nanoparticles for brain-targeting delivery in a sporadic Alzheimer’s disease mouse model: focus on antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and amyloidogenic pathways. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):1003. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14051003, PMID 35631589.

Tønnesen HH, Masson M, Loftsson T. Studies of curcumin and curcuminoids. XXVII. Cyclodextrin complexation: solubility, chemical and photochemical stability. Int J Pharm. 2002;244(1-2):127-35. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00323-x, PMID 12204572.

Sahu NK, Lariya NK. pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100 coated chitosan nanoparticles for targeted curcumin delivery in ulcerative colitis: formulation and optimization. Int J App Pharm. 2025;17(3):252-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.54408.

MacPherson BR, Pfeiffer CJ. Experimental production of diffuse colitis in rats. Digestion. 1978;17(2):135-50. doi: 10.1159/000198104, PMID 627326.

Lavelle A, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(4):223-37. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0258-z, PMID 32076145.

Khan MU, Khan S, Alshahrani SM, Irfan M. Eudragit S-100-coated chitosan-curcumin nanoparticles for ulcerative colitis: enhanced stability and targeted delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;220:1451-64.

Morris GP, Beck PL, Herridge MS, Depew WT, Szewczuk MR, Wallace JL. Hapten-induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(3):795-803. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90904-9, PMID 2914642.

Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenson WF. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(6):1344-50. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(84)90202-6, PMID 6092199.

Berger ML. On the true affinity of glycine for its binding site at the NMDA receptor complex. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1995;34(2):79-88. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(95)00028-g, PMID 8563036.

Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and practice of histological techniques. 6th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

Lee SJ, Park YJ. pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery systems: formulation and characterization. Polymers. 2020;12(12):2686.