Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 9, 63-69Original Article

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AND ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY OF BARLERIA GRANDIFLORA LEAF EXTRACTS WITH EXPLORATION OF PHARMACOGNOSTIC AND PHYTOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS

MALTI SAO, JAYA SHREE, RAJESH CHOUDHARY*

Shri Shankaracharya College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Shri Shankaracharya Professional University, Bhilai-490020, Chhattisgarh, India

*Corresponding author: Rajesh Choudhary; *Email: rajesh080987@gmail.com

Received: 05 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 01 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The Barleria grandiflora Dalz (Acanthaceae), known as Shwet keshariya and Dev Koranti, is widely used in Indian traditional medicine. The study aimed to investigate the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of B. grandiflora leaf extracts along with pharmacognostic and phytochemical analysis.

Methods: The present study included macroscopical, microscopical, phytochemical, and physicochemical analysis to standardize the plant materials. Fresh leaves were taken for morphological and microscopical studies. Total ash value, water-soluble ash, and acid-insoluble ash were determined. Loss on drying and a study of foreign organic matter were carried out. Phytochemical analysis was performed using chemical reactions, UV-visible spectrophotometers, and HPLC methods. Phenolic compounds and flavonoid contents were quantified using gallic acid and rutin equivalence methods. In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of leaf extracts (aqueous: BGAE, ethanolic: BGEE, and petroleum ether: BGPE) was assessed by using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) assay, respectively.

Results: The qualitative phytochemical analysis demonstrated that BGAE and BGEE contain phenolic and flavonoids as the major phytoconstituents. The BGEE showed significant (P<0.05) higher contents of phenolic and flavonoids than BGAE and BGPE. Results showed that B. grandiflora leaf extracts showed considerable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. IC50 values of BGAE, BGEE, and BGPE for the DPPH assay were found to be 221.6±7.92, 181.1±5.37, and 322.4±10.79 µg/ml, respectively, and IC50 values of BGAE, BGEE, and BGPE for the BSA assay were found to be 145.7±4.12, 74.03±7.15, and 194.6±3.51 μg/ml, respectively.

Conclusion: The results showed that BGEE had better antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity as compared to BGAE and BGPE. These effects might be due to the presence of higher phenolic and flavonoid contents. The current study showed a significant impact of data that helped determine the plant's identity, purity, and effectiveness, giving society access to effective and affordable medicine for use in the future.

Keywords: Barleria grandiflora, Anti-inflammatory activity, Antioxidant activity, DPPH assay, Phytochemical analysis

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i9.55437 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Antioxidants protect the living system from oxidative insults, which are a hallmark feature of systemic disorders, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes [1]. This oxidative damage is caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl, and nitric oxide (NO) radicals [2]. These ROS accumulations damage crucial biomolecules such as nucleic acids, lipids, proteins, polyunsaturated fatty acids, carbohydrates, and DNA in the living system and may lead to oxidative damage and inflammation [3]. Most of the antioxidants present in vascular plants are vitamins C and E, carotenoids, flavonoids, and tannins [4]. The naturally polyphenolic compounds, especially flavonoids, have been largely studied for their strong antioxidant capacity [5]. Presently, medicinal plants are one of the most important sources of phyto-biomolecules, including alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, and phytosterols, and these biomolecules demonstrate a variety of biological activities. Additionally, since the beginning of ancient civilization, herbs have played an important role in the management of several disorders. As per the World Health Organization, about 75% of the population still believes in traditional plant-based medicine [6, 7]. In this context, we explored a newer medicinal plant, Barleria grandiflora (table 1), belonging to the Acanthaceae family [8].

Table 1: Scientific classification of B. grandiflora

| S. No. | Classification | Description |

| 1 | Kingdom | Plantae |

| 2 | Sub-kingdom | Tracheobionta |

| 3 | Division | Magnoliophyta |

| 4 | Class | Magnoliopsida |

| 5 | Sub-class | Asteridae |

| 6 | Order | Scrophulariales |

| 7 | Family | Acanthaceae |

| 8 | Genus | Barleria |

| 9 | Species | Barleria grandiflora Dalz |

| 10 | Habit | Shrub |

| 11 | Common name | Dev-koranti, Shwet-koranti |

A large genus of herbs and shrubs, Barleria (Acanthaceae), has over 230 species, most of which are found in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. India has over thirty species, several of which are noted for their ornamental and/or therapeutic benefits. Some of the important species of this genus are Barleria prionitis, Barleria greenii, Barleria albostellata, Barleria cristata, Barleria barleriastrigosa, Barleria tomentosa, etc. In some Barleria species, biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antileukemic, and hypoglycemic have been reported [8]. B. grandiflora, also known as Dev-koranti, is in the regions of Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, and Uttarakhand. B. grandiflora has a variety of pharmacological activities, like antifungal activity [9], and antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity [10]. Therefore, current research aims to explore the pharmacognostic and phytochemical properties of B. grandiflora and evaluate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of leaf extracts of B. grandiflora using the in vitro models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials

In December 2024, fresh B. grandiflora leaves were procured from the Durg area of Chhattisgarh, India. Dr. Praveen Joshi, a professor at the Ayurvedic College in Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India, verified the authenticity of the plant. For future reference, a voucher specimen (Ref. No. SSPU/SSCPS/Res Cell/2024, dated 20 Feb 2024) has been placed at the same location's herbarium.

Chemicals and reagents

Gallic acid (Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., India), rutin (Himedia Laboratories, India), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, Central Drug House, Pvt. Ltd., India), bovine albumin serum (BSA, Himedia Laboratories, India), HPLC grade methanol (Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., India), and Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagents (Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., India) were procured from the departmental chemical store. All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Pharmacognostic evaluation

Macroscopic and organoleptic evaluation of B. grandiflora leaves

Macroscopic and organoleptic properties of B. grandiflora, like color, odor, taste, shape, and size, were examined by sensory organs [11, 12].

Microscopic evaluation of B. grandiflora leaves

Microscopic evaluation of the B. grandiflora leaves was carried out by taking the transverse sections of the fresh leaves using a sharp blade. The sections were transferred to a watch glass containing water, stained with safranin, washed, and mounted on a slide in glycerin. Microscopic characteristics were observed under a microscope [13].

Physicochemical evaluation of B. grandiflora leaves

The physicochemical properties of the B. grandiflora leaves were evaluated as per the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO). The parameters, such as moisture content (loss on drying method), ash values (total ash, acid-insoluble ash, and water-soluble ash), and extractive values (water-soluble and alcohol-soluble extractives), were determined using the powdered drug [11, 12, 14].

Determination of ash values

Ash values help to determine the quality and purity of the crude drugs. Ash, which is composed of inorganic materials including silica and metallic salts, is produced when crude pharmaceuticals are meticulously burned at 450 °C. When the crude medicine is prepared for marketing, a higher ash level indicates contamination, substitution, adulteration, or negligence.

A. Total ash: It is the entire amount of material left over after the drug powder has been completely burned at 450 °C to eliminate all carbon. Two gs of dried and powdered crude medication were precisely weighed in three tared silica crucibles before being burned in a muffle furnace at 450 °C. After cooling in a desiccator, the crucibles were weighed. The weight of the air-dried powder was used to compute the percentage of total ash.

B. Acid-insoluble ash: After using hydrochloric acid to extract the whole ash, it is obtained. It explains the pollution caused by silicious materials such as sand and dust. Following the process, 25 ml of 2 M hydrochloric acid was added to the ash and heated for five minutes. On ashless filter paper, the insoluble material was gathered. Hot water was used once more to wash the intractable material. After that, the filter paper containing the filtrate was lit, allowed to cool in a desiccator, and weighed. The amount of acid-insoluble ash concerning the medication that was air-dried was computed.

C. Water-soluble ash value: After 5 min of boiling with 25 ml of water, the ash was filtered through ashless filter paper. Hot distilled water was used to cleanse the residue that had accumulated on the filter paper. After being left to dry, the filter paper was burned at 450 °C for 15 min. To get the water-soluble ash, the weight of the insoluble ash was calculated and deducted from the total amount of ash collected. With reference to the dried sample, the proportion of water-soluble ash was computed.

Determination of solvent extractive values

The amount of active ingredients in a specific amount of crude plant material following extraction using solvents such as water, alcohol, ether, etc., is represented by solvent extractive values. It is the first stage of making natural medications. A molecule can be either water-soluble or water-insoluble, depending on its molecular structure. Organic solvents like alcohol, chloroform, and others could be used to extract substances that are insoluble in water. The extractive values of ether, alcohol, and water were established in the present investigation. Briefly, the shade-and air-dried, finely powdered plant material (5g) was extracted using 100 ml of selected solvents (petroleum ether/ethanol/water) in a closed flask for 24 h. Thereafter, the extractive solution was filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness at 105 °C in a tared, flat-bottomed, shallow dish and weighed. The percentage extractive value was calculated against the air-dried drug.

Loss on drying

In a tared silica crucible, 2 g of precisely weighed, air-dried, finely powdered crude drug was put. A thin, even layer of powder was applied. After that, the crucible was kept for 4 h at 105 °C. The crucible was removed from the oven after 4 h, allowed to cool at room temperature in a desiccator, and then weighed. The moisture that stays with the hygroscopic plant material even after air-drying to a constant weight is explained by the weight differential.

Determination of foreign organic matter

Foreign organic material is defined as parts of the organ or organs other than the parts named in the definition and description from which the drug is derived. It includes any organs of the concerned plant other than those named in the definition and description. Insects and other animal contamination are examples of matter that does not originate from the plant. After being weighed, the 100 g of powder was applied thinly to a glass slide. A dissecting microscope with a 10x lens was used to examine the sample, and any foreign organic debris was manually removed as thoroughly as possible. The percentage of foreign organic materials was calculated by weighing the quantity.

Extraction of plant materials

After being cleaned with tap water, the freshly harvested B. grandiflora leaves were allowed to air dry at room temperature for 2 to 3 w before being ground into a coarse powder. After the leaves were defatted with petroleum ether and extracted using a Soxhlet apparatus (at 70 °C) with water (BGAE), ethanol (BGEE), and petroleum ether (BGEE). The extracts were concentrated by using a rotary vacuum evaporator (at 70 °C); thereafter, the concentrated extracts were filtered and evaporated from the solvent till dry by using a vacuum oven (at 70 °C). The dried extracts were stored in amber-colored bottles in the refrigerator (at 2-8 °C) until analysis.

Phytochemical analysis

Preliminary phytochemical analysis

Phytochemical screening was carried out to identify the secondary metabolites present in extracts [15]. The following tests were performed:

A. Test for tannins: Two milliliters of ferric chloride were added to two milliliters of the filtered extract in a test tube. The appearance of a blue-black precipitate indicated the presence of tannins.

B. Test for saponins: Five milliliters of distilled water were added to 0.5 ml of the extract in a test tube. After vigorous shaking, the presence of saponins was confirmed by the formation of a stable, persistent foam.

C. Test for terpenoids (Salkowski test): In a test tube, 0.5 ml of extract were mixed with two milliliters of chloroform. Then, three milliliters of concentrated sulfuric acid were added. A reddish-brown coloration at the interface indicated the presence of terpenoids.

D. Test for cardiac glycosides: One milliliter of glacial acetic acid and a drop of ferric chloride solution were added to two milliliters of the extract. The formation of a brown ring at the interface indicated the presence of glycosides.

E. Test for flavonoids: Five milliliters of diluted ammonia and one milliliter of concentrated sulfuric acid were added to 0.5 ml of the extract. A yellow coloration that disappeared upon standing indicated the presence of flavonoids.

F. Test for phenolic compounds: Two milliliters of extract were mixed with one milliliter of ferric chloride. The development of a green or blue color indicated the presence of phenolic compounds.

G. Test for alkaloids: A few drops of Mayer’s reagent were added to one milliliter of the extract. The formation of a creamy yellow precipitate confirmed the presence of alkaloids.

Qualitative phytochemical analysis by UV-visible spectro-photometer and HPLC

The extracts (BGAE, BGEE, and BGPE) were further subjected to qualitative phytochemical identification by using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-1780, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc., USA) and HPLC (Agilent 1100 Isocratic HPLC system, Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). For the UV-spectrophotometer analysis, extract samples (50 µg/ml in HPLC-grade methanol) were scanned at 200 to 780 nm to identify the λ max and compared with the λ max of standard gallic acid (10 µg/ml in HPLC-grade methanol) and rutin (10 µg/ml in HPLC-grade methanol) for qualitative identification of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. The following conditions for the HPLC analysis were adopted: a CredchromC18 column (250 mm x 4.6 mm x 5 µm), HPLC-grade methanol as a mobile phase, and 1 ml/min flow rate, and 20 µl for injection. The extract samples were run at 257 nm for 5 min and compared with the standard rutin as a phytochemical marker.

Quantitative phytochemical analysis for phenolic and flavonoids

Estimation of total phenolic content

The total phenolic content of the extracts of B. grandiflora was determined using the gallic acid equivalence method [16, 17]. Briefly, a 4 mg/ml stock solution of each extract, BGAE, BGEE, and BGPE, was prepared in DMSO. The 0.2 ml of each extracted sample from the stock solution was taken in a fresh test tube, and 1.5 ml of the Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent (10 % v/v) was added and kept for 5 min at room temperature. Each reactant was then combined with 1.5 ml of 6% w/v sodium carbonate solution. A UV-visible spectrophotometer was used to measure the colorful reaction products at 725 nm against a blank after 90 min. Using a gallic acid standard curve (2–20 µg/ml), the total phenolic content was measured and reported as the mg equivalent of gallic acid per g of dry weight (mgE GA/g).

Estimation of total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid content of the extracts of B. grandiflora was determined using the rutin equivalence method [16, 18]. In short, methanol (1.5 ml), aluminum chloride (0.1 ml, 10% w/v), potassium acetate (0.1 ml, 1M), and distilled water (2.8 ml) were added to 0.5 ml of each extract (4 mg/ml). For half an hour, the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature. The result was then measured against a blank at 415 nm. A rutin standard curve (2–20 µg/ml) was used to quantify the total flavonoid concentration, which was then represented as the mg equivalent of rutin per g of dry weight (mgE rutin/g).

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of the extracts of B. grandiflora was determined by using the ability to scavenge 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals [19]. In short, we combined 1 ml of each extract (50–200 µg/ml) with 3 ml of a 0.1 mmol methanolic solution of DPPH. After 30 min of dark incubation at room temperature, the reaction mixture was measured at 517 nm against a blank. Using the following formula, the % inhibition of DPPH radicals was determined:

![]()

Where Ac is the absorbance of the DPPH control, and At is the absorbance of the test sample of the extract.

Anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory activity of the extracts of B. Grandiflora was determined by using a protein denaturation assay [20]. Briefly, 0.02 ml of each extract (50-200 µg/ml) was combined with 0.2 ml of bovine albumin serum (BSA, 1 % w/v) and 4.78 ml of phosphate buffer saline (pH 6.4). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, and afterward heated at 70 °C for 5 min. The reaction product was measured against a blank at 660 nm after cooling. Using the following formula, the % inhibition of protein denaturation was determined:

![]()

Where Ac is the absorbance of the BSA control, and At is the absorbance of a test sample of the extract.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

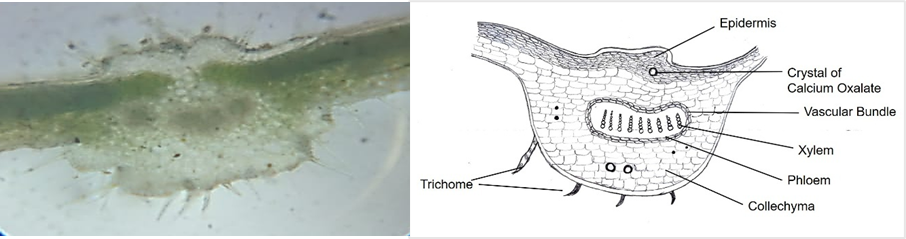

The macroscopic examination of B. grandiflora leaves was first conducted, as it is an essential requirement of standardization. The observation of the macroscopic examination is presented in table 2 and fig. 1. The morphological evaluation of fresh leaves of B. grandiflora is light green with a characteristic odor. The leaves are bitter. The size of the leaf is 10-20 cm long. The leaf is elliptic, lanceolate, acuminate, and glabrous, with a base tapering in shape.

Fig. 1: Macroscopic evaluation of B. grandiflora leaves

Table 2: Macroscopic features of B. grandiflora leaves

| S. No. | Parameters | Observation |

| 1 | Color | Green |

| 2 | Odor | Characteristic |

| 3 | Taste | Bitter |

| 4 | Size | 10-20 cm long |

| 5 | Leaf-stalk | 1 cm long |

| 6 | Shape | Elliptic-lanceolate, acuminate, glabrous with base tapering |

Microscopic examination (fig. 2) of B. grandiflora leaves revealed features like epidermis, vascular bundles, and stomata present in the lower epidermis and absent in the upper epidermis. The transverse section of leaves indicates that the first layer is a single layer of the epidermis. The vascular bundle was presented centrally, and xylem vessels were arranged in a radial row surrounded by phloem.

Fig. 2: Microscopic evaluation of B. grandiflora leaves

The physicochemical parameters (table 3) of the powdered drug and phytochemical screening (table 4) of the extract were also performed in the research. The physicochemical parameter can be used for the assessment of the purity and quality of crude drugs. The total ash values of the powdered drug, water-soluble ash, and acid-insoluble ash were identified as impurities present along with the drug [11, 12]. The observation of ash value is presented in table 3. The extractive values presented an idea about the active constituents present in crude drugs. These values are helpful in the assessment of the solubility of a chemical constituent in a particular solvent [13]. The extractive values are compiled in table 3. The results demonstrated that aqueous and ethanolic extracts show higher extractive value as compared to petroleum ether extract, indicating a higher presence of chemical constituents. The percentage of loss on drying is necessary for the determination of microorganism growth, such as bacteria, fungi, and yeast, which causes the physical and chemical changes of crude drugs [9]. The loss on drying and foreign organic matter are compiled in table 3.

Table 3: Physicochemical properties of B. grandiflora leaves

| S. No. | Parameters | Observations |

| 1 | Ash Value (% w/w) | |

| Total ash value | 18.43±0.46 | |

| Water-soluble ash | 3.93±0.08 | |

| Acid-insoluble ash | 8.83±0.20 | |

| 2 | Extractive value (% w/w) | |

| Water-soluble extractive | 13.87±0.75 | |

| Ethanol-soluble extractive | 15.90±0.88 | |

| Ether-soluble extractive | 8.13±0.17 | |

| 3 | Loss on drying (% w/w) | 9.83±0.14 |

| 4 | Foreign organic matter (% w/w) | 0.036±0.003 |

Results are expressed in mean±SEM, n = 3

The qualitative analysis of major phytochemicals of the plant extract of B. grandiflora indicates the presence of tannins, saponins, terpenoids, glycosides, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and alkaloids (table 4). Ethanolic and petroleum ether extracts show the presence of all phytochemical constituents, while glycosides were absent in the aqueous extract.

Table 4: Qualitative test of phytochemicals in the leaf of B. grandiflora

| S. No. | Phytochemicals | Test performed | BGAE | BGEE | BGPE |

| 1 | Tannins | With Ferric chloride solution | Present | Present | Present |

| 2 | Saponins | Frothing test | Present | Present | Present |

| 3 | Terpenoids | With Chloroform and conc. Sulphuric acid | Present | Present | Present |

| 4 | Glycosides | With Glacial acetic acid and ferric chloride solution | Absent | Present | Present |

| 5 | Flavonoids | With Dil. Ammonia and conc. sulphuric acid | Present | Present | Present |

| 6 | Phenolic compounds | With Ferric chloride solution | Present | Present | Present |

| 7 | Alkaloids | Mayer’s reagent | Present | Present | Present |

BGAE: B. grandiflora aqueous extract, BGEE: B. grandiflora ethanolic extract, and BGPE: B. grandiflora petroleum ether extract.

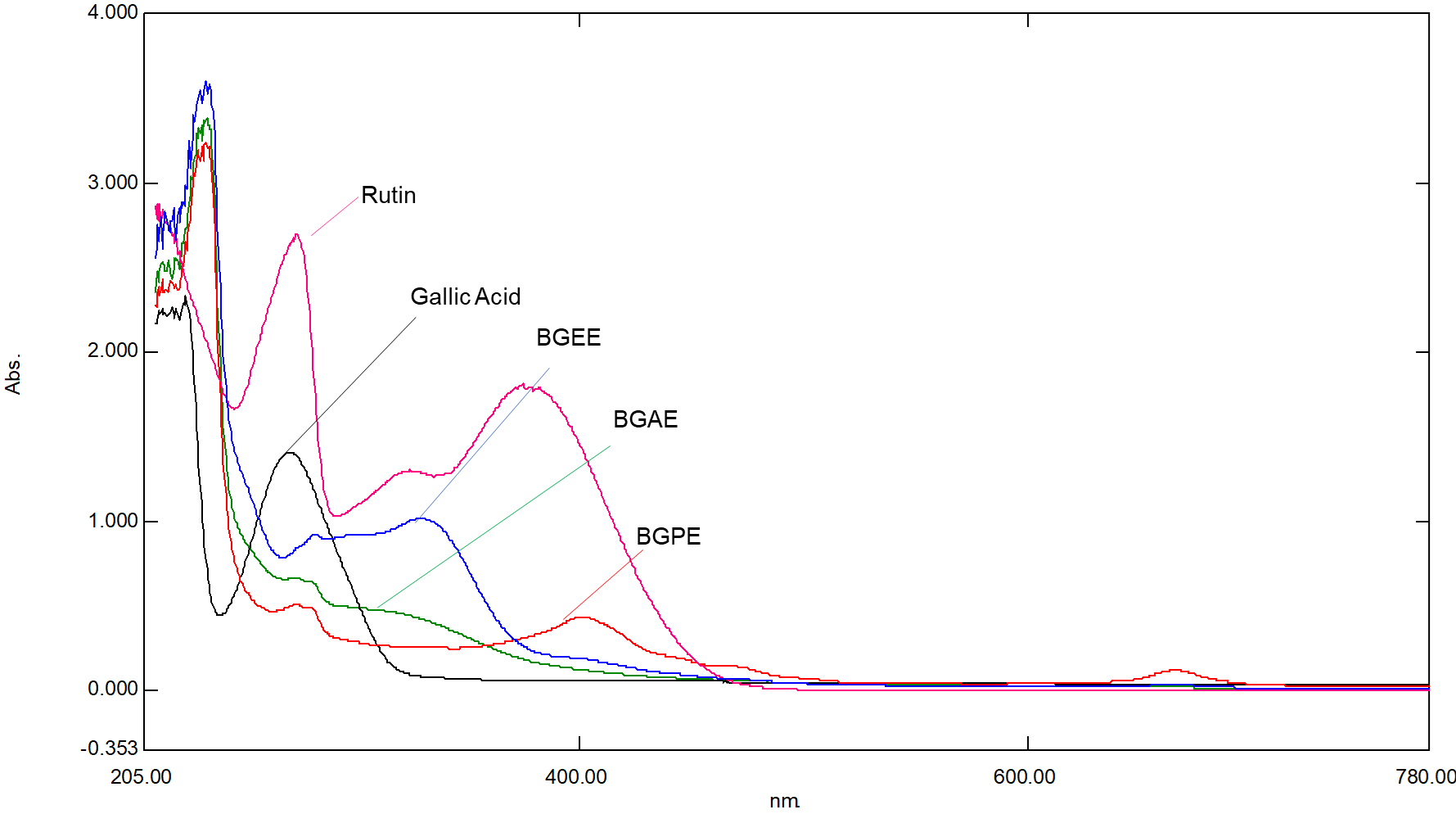

Further, qualitative analysis of phytochemicals, especially phenolic compounds and flavonoids, was performed using UV-visible spectrophotometric and HPLC techniques. The UV-visible spectrum is depicted in fig. 3, and λ max is presented in table 5. It is well known that the absorbance at a specific wavelength of the UV-visible spectrophotometer indicates the presence of phytochemicals in the sample, and absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration. The results demonstrated that BGAE shows λ max at around 272.5 and 279.5 nm, BGEE shows λ max at around 328.5 and 281.5 nm, and BGPE shows λ max at around 273 and 279.5 nm (table 5). Moreover, results also demonstrated that the concentration of active phytoconstituents in BGEE is considerably higher than in BGAE and BGPE, which is indicated by the absorbance intensity of BGEE. For the qualitative analysis of phytoconstituents, gallic acid and rutin were used as standard markers for phenolics and flavonoids, respectively. Gallic acid showed λ max at 270 nm, and rutin showed λ max at 273.5 nm and 374.5 nm. As per the literature, the absorption spectra of flavonoids consist of two major bands, band I at 300 to 380 nm and band II at 240 to 295 nm [21], which were observed in BGEE.

Fig. 3: UV-visible spectra of B. grandiflora leaf extracts

Table 5: Major peaks on UV-visible spectrophotometer of B. grandiflora leaf extracts

| S. No. | Test samples | Concentration (µg/ml) | λ max (nm) | Absorbance |

| 1 | BGAE | 50 | 272.5 279.5 |

0.66 0.64 |

| 2 | BGEE | 50 | 328.5 281.5 |

1.01 0.92 |

| 3 | BGPE | 50 | 273 279.5 401 666 |

0.50 0.48 0.43 0.12 |

| 4 | Gallic Acid | 10 | 270 | 1.40 |

| 5 | Rutin | 10 | 273.5 374.5 |

2.69 1.87 |

BGAE: B. grandiflora aqueous extract, BGEE: B. grandiflora ethanolic extract, and BGPE: B. grandiflora petroleum ether extract

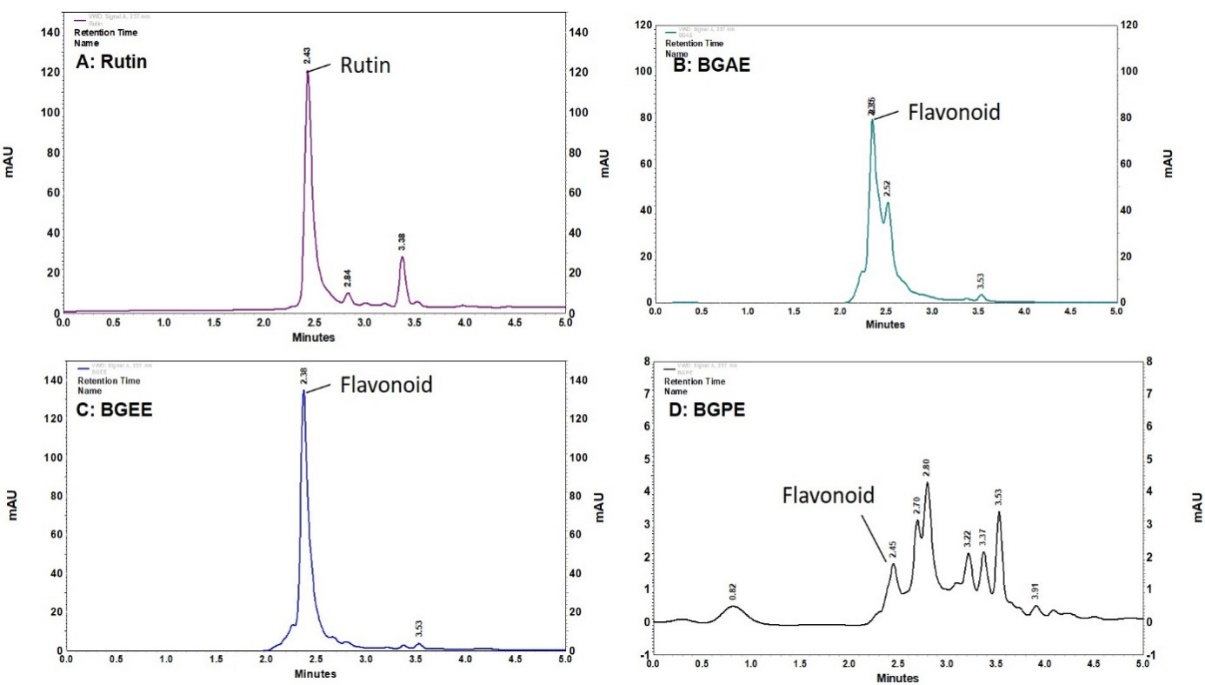

Fig. 4: HPLC analysis of B. grandiflora leaf extracts. (A) rutin, (B) BGAE, (C) BGEE, and (D) BGPE. BGAE: B. grandiflora aqueous extract, BGEE: B. grandiflora ethanolic extract, and BGPE: B. grandiflora petroleum ether extract

The result of HPLC analysis is presented in fig. 4. The HPLC analysis indicates the presence of flavonoids, which was confirmed by using rutin as a phytochemical marker. The retention time of BGAE, BGEE, and BGPE was found to be 2.35, 2.38, and 2.45 min, respectively, which is closely related to the standard rutin (2.43 min). The qualitative HPLC phytochemical analysis indicates the presence of flavonoids, especially rutin class (flavanol), as a major active constituent in the BGAE and BGEE. Whereas BGPE showed multiple peaks in UV and HPLC spectra, indicating the presence of a variety of phytochemicals in petroleum ether extract, but in lower concentrations.

Phenolics and flavonoids are the most important phytomolecules, having a variety of pharmacological activities through their potent antioxidant activity [22, 23]. The present study used UV-visible spectrophotometric methods to quantify the total phenolic and flavonoid contents using gallic acid (phenolic compound) and rutin (flavonoid) as standard markers. The results are presented in table 6. The results showed that BGEE contains higher phenolic (92.83±1.14 mgE GA/g) and flavonoid (62.19±2.54 mgE Rutin/g) content when compared to the BGAE and BGPE.

Table 6: Total phenolic and flavonoid contents of B. grandiflora leaf extracts.

| S. No. | Total phenolic contents (mgE GA/g) | Total flavonoid contents (mgE Rutin/g) | |

| 1 | BGAE | 25.36±0.52 | 11.23±0.63 |

| 2 | BGEE | 92.83±1.14 | 62.19±2.54 |

| 3 | BGPE | 4.46±0.23 | 2.93±0.16 |

Results are expressed in mean±SEM, n = 3. BGAE: B. grandiflora aqueous extract, BGEE: B. grandiflora ethanolic extract, and BGPE: B. grandiflora petroleum ether extract

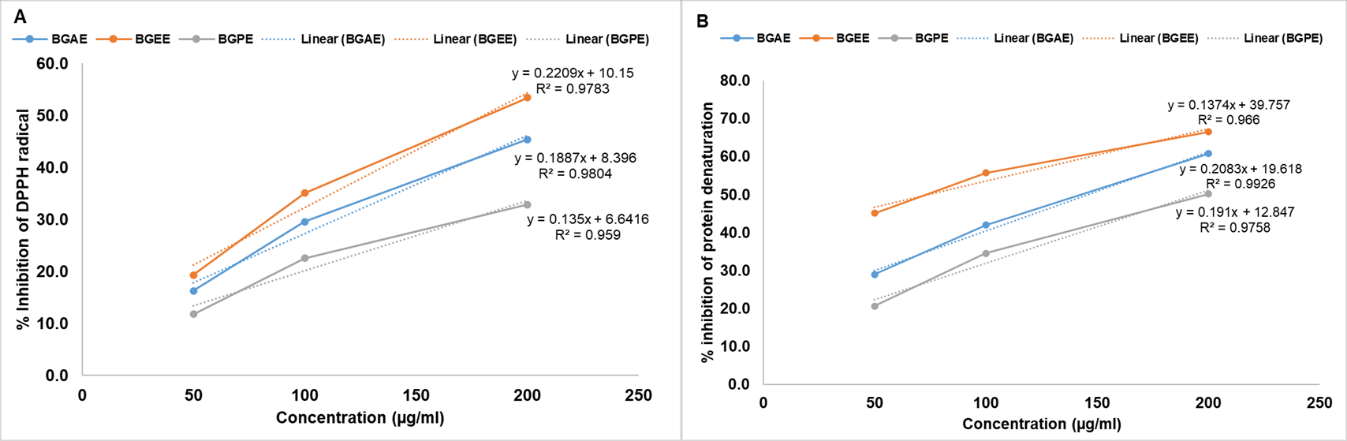

In addition, the present study also explored and compared the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of B. grandiflora leaf extracts. The DPPH radical, a widely used indicator of antioxidant activity, is a rapid, simple, and cost-effective method for assessing the scavenging and hydrogen-supplying capabilities of compounds. The DPPH test involves the elimination of DPPH, a stabilized free radical. DPPH is a dark-colored crystalline compound composed of stable free radical particles. Notably, it is a well-known radical and a commonly employed antioxidant test [24, 25]. The DPPH assay was established 100 y ago to assess the antioxidant activity of chemical substances. The electron-rich substituents, like phenolic compounds, are excellent H-donors that can quickly scavenge all types of radicals, including DPPH radicals [24]. In this context, the possible scavenging activity of B. grandiflora leaf extracts was assessed in the DPPH assay. Results showed that B. grandiflora leaf extracts showed considerable antioxidant activity, which was indicated by the inhibition of DPPH free radicals. IC50 values of BGAE, BGEE, and BGPE for the DPPH assay (fig. 5A and table 7) were found to be 221.6±7.92, 181.1±5.37, and 322.4±10.79 µg/ml, respectively. The result of the anti-inflammatory activity of B. grandiflora leaf extracts is presented in fig. 5B and table 7. The IC50 values for anti-inflammatory activity were found to be 145.7±4.12 μg/ml in BGAE, 74.03±7.15 μg/ml in BGEE, and 194.6±3.51 μg/ml in BGPE. The results of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity indicated that BGEE had better activity compared to BGAE and BEPE.

Table 7: IC50 values of B. grandiflora leaf extracts on the DPPH assay and Anti-inflammatory assay

| S. No. | Extract | DPPH scavenging activity (IC50 Value) | Anti-inflammatory assay (IC50 Value) |

| 1 | BGAE | 221.6±7.92 | 145.7±4.12 |

| 2 | BGEE | 181.1±5.37 | 74.03±7.15 |

| 3 | BGPE | 322.4±10.79 | 194.6±3.51 |

Results are expressed in mean±SEM, n = 3. BGAE: B. grandiflora aqueous extract, BGEE: B. grandiflora ethanolic extract, and BGPE: B. grandiflora petroleum ether extract

Fig. 5: Effect of B. grandiflora leaf extracts on (A) DPPH assay and (B) Anti-inflammatory activity

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study explored the pharmacognostic, physicochemical, and preliminary phytochemical properties of the B. grandiflora leaves. The preliminary phytochemical evaluation indicates the presence of phenolic and flavonoids as the major phytoconstituents in aqueous and ethanolic extracts. The results showed that ethanolic extract (BGEE) had better antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity as compared to the BGAE and BGPE. These effects might be due to the presence of higher phenolic and flavonoid contents. The present study is limited to preliminary phytochemical and biological studies by the in vitro method. However, these findings may contribute to establishing its therapeutic value in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is thankful to Dr. Praveen Joshi, Professor, Ayurvedic College, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India, for authenticating the plant and the Department of Pharmacognosy and Pharmacology of the institute for providing the necessary research facilities to carry out the research work.

FUNDING

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Malti Sao was involved in investigation, data collection, and manuscript writing. Jaya Shree was involved in data analysis and manuscript writing, and Rajesh Choudhary was involved in conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and manuscript review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K. Reactive oxygen species toxicity, oxidative stress and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 2023 Oct;97(10):2499-574. doi: 10.1007/s00204-023-03562-9, PMID 37597078.

Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V. Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017 Aug 19;2017:8416763. doi: 10.1155/2017/8416763, PMID 28819546.

Siriwatanametanon N, Fiebich BL, Efferth T, Prieto JM, Heinrich M. Traditionally used thai medicinal plants: in vitro anti-inflammatory, anticancer and antioxidant activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010 Jul 20;130(2):196-207. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.036, PMID 20435130.

Maury GL, Rodriguez DM, Hendrix S, Arranz JC, Boix YF, Pacheco AO. Antioxidants in plants: a valorization potential emphasizing the need for the conservation of plant biodiversity in Cuba. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 Oct 27;9(11):1048. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111048, PMID 33121046.

Farombi EO, Fakoya A. Free radical scavenging and antigenotoxic activities of natural phenolic compounds in dried flowers of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005 Dec;49(12):1120-8. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500084, PMID 16254885.

Garaniya N, Bapodra A. Ethno botanical and phytophrmacological potential of Abrus precatorius L.: a review. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014 May 14;4 Suppl 1:S27-34. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C1069, PMID 25183095.

Kashyap P, Yadav A, Choudhary R, Sahu H, Shree J, Jha AK. Anticataract activity of Abrus precatorius seed extract against diabetic induced cataract. Adv Pharmacol Pharm. 2025 Jan 1;13(1):28-36. doi: 10.13189/app.2025.130104.

Gangaram S, Naidoo Y, Dewir YH, El Hendawy S. Phytochemicals and biological activities of Barleria (Acanthaceae). Plants (Basel). 2021 Dec 28;11(1):82. doi: 10.3390/plants11010082, PMID 35009086.

Kumari S, Jain P, Sharma B, Kadyan P, Dabur R. In vitro antifungal activity and probable fungicidal mechanism of aqueous extract of Barleria grandiflora. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015 Apr 1;175(8):3571-84. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1527-0, PMID 25672323.

Sawarkar HA, Kashyap PP, Kaur CD, Pandey AK, Biswas DK, Singh MK. Antimicrobial and TNF-alpha inhibitory activity of Barleria prionitis and Barleria grandiflora: a comparative study. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2016 Aug 1;50(3):409-17. doi: 10.5530/ijper.50.3.14.

Khandelwal KR. Practical pharmacognosy. Pragati Books Pvt Ltd; 2008.

WHO. Quality control methods for herbal materials: libros digitales World Health Organization (WHO); 2011.

Junejo JA, Ghoshal A, Mondal P, Nainwal L, Zaman MK, Khumanthem D. In vivo toxicity evaluation and phytochemical physicochemical analysis of Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw. leaves a traditionally used North-Eastern Indian vegetable. Adv Biol Res. 2015 Oct 1;6(5):175-81. doi: 10.15515/abr.0976-4585.6.5.175181.

Harborne A. Phytochemical methods a guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. Springer Science+Business Media; 1998.

Jyothiprabha V, Venkatachalam P. Preliminary phytochemical screening of different solvent extracts of selected lndian spices. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2016 Feb 15;5(2):116-22. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2016.502.013.

Bhatti MZ, Ali A, Ahmad A, Saeed A, Malik SA. Antioxidant and phytochemical analysis of Ranunculus arvensis L. Extracts. BMC Res Notes. 2015 Jun 30;8(1):279. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1228-3, PMID 26123646.

Mahani, Mohammed Ahmed AO, Nurhadi B. Evaluate antioxidant activity phenolic content and colour of Indonesian stingless bee honey and sting bee honey cultivated in Indonesia. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022 Nov 7;15(11):42-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i11.46091.

Chang CC, Yang MH, Wen HM, Chern JC. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colometric methods. J Food Drug Anal. 2002 May 16;10(3):3. doi: 10.38212/2224-6614.2748.

Soni P, Choudhary R, Bodakhe SH. Effects of a novel isoflavonoid from the stem bark of Alstonia scholaris against fructose-induced experimental cataract. J Integr Med. 2019 Jun 8;17(5):374-82. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2019.06.002, PMID 31227424.

Gunathilake KD, Ranaweera KK, Rupasinghe HP. In vitro anti-inflammatory properties of selected green leafy vegetables. Biomedicines. 2018 Nov 19;6(4):107. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6040107, PMID 30463216.

Taniguchi M, La Rocca CA, Bernat JD, Lindsey JS. Digital database of absorption spectra of diverse flavonoids enables structural comparisons and quantitative evaluations. J Nat Prod. 2023 Apr 28;86(4):1087-119. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00720, PMID 36848595.

Ullah A, Munir S, Badshah SL, Khan N, Ghani L, Poulson BG. Important flavonoids and their role as therapeutic agent. Molecules. 2020 Nov 11;25(22):5243. doi: 10.3390/molecules25225243, PMID 33187049.

Ashraful Md I, Dipankar C, Sreebash Chandra B, Md Hasan ALI, Md Farhad S, Md Samrat Mohay Menul I. Assessment of total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC) and antidiarrheal and antioxidant activities of Dioscorea bulbifera tuber extract. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024 Nov 7;17(11):195-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024v17i11.51957.

Gulcin I, Alwasel SH. DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes. 2023;11(8):2248. doi: 10.3390/pr11082248.

Sulistyowati EB, Elya B, Nur S, Iswandana R. Formulation antioxidant and anti-aging activity of Rubus fraxinifolius fraction. Int J App Pharm. 2024 Jul 7;16(4):121-8. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i4.51013.