Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 9, 21-27Review Article

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC ADVERSE EFFECTS OF NEWER SEDATIVE HYPNOTICS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

1PRANAB DAS*, 2DARADI DAS, 3ROHIT TIGGA

1,2Department of Pharmacology, Pragjyotishpur Medical College and Hospital, Guwahati, Assam, India. 3Department of Pharmacology, Silchar Medical College and Hospital, Silchar, Assam, India

*Corresponding author: Pranab Das; *Email: pranabdas2580123@gmail.com

Received: 07 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 04 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

This systematic review aimed to evaluate and synthesise existing evidence on neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with newer sedative-hypnotics, particularly the Z-drugs (zolpidem, zopiclone, eszopiclone, zaleplon) and the dual orexin receptor antagonist suvorexant. The review sought to identify common adverse drug reaction (ADR) patterns, determine high-risk populations, and assess the neuropsychiatric safety profiles of these agents.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (limited to the first 200 results). Eligible studies included observational studies, pharmacovigilance reports, randomised controlled trials, and systematic reviews reporting neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs) linked to the target medications in adult population. Data extraction and screening were performed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. A qualitative thematic synthesis approach was adopted due to heterogeneity in outcome measures and study designs.

Out of 20 identified records, 9 studies met the inclusion criteria for core synthesis. The most frequently reported neuropsychiatric ADRs included sleepwalking, hallucinations, suicidality, and falls. Zolpidem was implicated in the widest range of reactions, followed by zopiclone and eszopiclone. Suvorexant exhibited a comparatively milder adverse drug reaction (ADR) profile, although somnolence and hallucinations were still observed. Elderly individuals, psychiatric patients, and those using high doses or non-prescribed medications emerged as particularly high-risk populations.

In conclusion, newer sedative-hypnotics, especially Z-drugs, are associated with a diverse spectrum of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, warranting caution in vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Zolpidem, Z-drugs, Suvorexant, Neuropsychiatric ADRs, Insomnia, Sedatives, Hypnotics, Adverse drug reactions, Qualitative synthesis, Systematic review

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i9.55462 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is a highly prevalent and often underdiagnosed health disorder that affects individuals across all age groups worldwide. It is primarily characterized by difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep and is commonly associated with impaired daytime functioning, including fatigue, cognitive disturbances, mood alterations, and diminished quality of life. Epidemiological surveys have consistently shown that a significant proportion of the adult population reports symptoms of insomnia, with chronic cases often persisting for months to years if left untreated [1].

In clinical settings, when non-pharmacological treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy fail to provide adequate relief, pharmacotherapy becomes the mainstay. Historically, benzodiazepines were widely prescribed due to their sedative and anxiolytic properties. However, prolonged use of these agents has been associated with a wide range of adverse effects including psychomotor impairment, memory disturbances, development of tolerance and dependence, and an increased risk of falls, particularly in older adults [2]. These safety concerns have led to the development and adoption of newer sedative-hypnotics, which are now preferred in many clinical guidelines.

Among the newer agents, the non-benzodiazepine “Z-drugs” such as zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon, and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) like suvorexant, have gained popularity for their shorter half-lives, targeted mechanisms of action, and perceived lower potential for dependence [3]. However, emerging evidence from pharmacovigilance databases, clinical studies, and post-marketing reports has increasingly highlighted a spectrum of neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with these medications [4].

Zolpidem, in particular, has been extensively studied due to a substantial number of spontaneous reports linking its use to neuropsychiatric side effects. These include hallucinations, vivid dreams, confusion, agitation, and more complex behaviours such as sleepwalking, sleep-eating, and even sleep-driving, often occurring without the patient's awareness or recollection [5]. Several case reports and systematic reviews have also documented episodes of mania and mood dysregulation triggered by zolpidem, raising concerns about its use in individuals with underlying psychiatric vulnerabilities [6]. Moreover, observational studies have revealed the potential for misuse and overuse of zolpidem, especially in populations with limited access to regular psychiatric follow-up or who engage in self-medication practices [7].

The use of zopiclone has similarly been linked to a range of behavioural and cognitive disturbances, particularly when prescribed in higher doses or in combination with other psychotropic medications. A retrospective study in psychiatric inpatients showed that the addition of zopiclone was sometimes associated with increased aggression and disinhibition, raising further questions about its behavioural safety profile [8]. Likewise, newer agents like suvorexant have not been free from concern. Although initially marketed as a more selective and safer alternative, recent randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have reported neuropsychiatric complications such as confusion, abnormal dreams, and delirium, particularly among elderly or medically complex patients [9, 10].

The concerns extend to melatonin receptor agonists such as ramelteon, which, though generally well tolerated, have been explored for their role in delirium prevention in elderly postoperative patients. While some studies suggest potential benefits, others have failed to demonstrate significant superiority over placebo, and concerns remain regarding their efficacy and long-term behavioural safety in vulnerable groups [11]. In addition, large-scale pharmacovigilance studies have associated the use of newer hypnotics, including eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem, with serious complex sleep behaviours, some of which resulted in injury or death, further reinforcing the need for cautious prescribing [12].

Despite the availability of isolated case reports, pharmacovigilance summaries, and small-scale clinical studies, there remains a clear gap in the literature regarding a comprehensive synthesis of the neuropsychiatric adverse effects associated with these agents across study designs and patient populations. Such a gap is clinically significant, given the growing trend of off-label, long-term, or unsupervised use of these medications in psychiatric, elderly, and medically complex patients like populations that already possess an inherently higher risk for behavioural and cognitive complications.

The present systematic review was undertaken to address this unmet need. It aims to consolidate available evidence on the neuropsychiatric adverse effects of newer sedative-hypnotics, particularly focusing on drugs such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon, zopiclone, suvorexant, and ramelteon. By systematically evaluating data from randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and pharmacovigilance reports, this review seeks to identify the nature, frequency, and patterns of reported ADRs, as well as the subgroups most vulnerable to these reactions. Through this effort, we hope to provide clinicians with a more nuanced understanding of the safety profiles of these widely prescribed agents, thereby enabling more informed and individualized treatment decisions in the management of insomnia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines, ensuring transparency, replicability, and methodological rigor at every stage of the review process.

Eligibility criteria

To ensure the relevance and reliability of included studies, predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome) framework. Studies were eligible if they involved adults aged 18 years or older who were prescribed newer sedative-hypnotic medications across any clinical setting, including outpatient, inpatient, and intensive care units. The intervention of interest included newer sedative-hypnotics such as Z-drugs (zolpidem, zopiclone, eszopiclone, zaleplon) and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs), specifically suvorexant. While a comparator was not mandatory for study inclusion, both comparative and non-comparative studies, including observational studies, pharmacovigilance data, case reports, and case series were considered if they reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects. Eligible outcomes included the occurrence of any neuropsychiatric side effects such as hallucinations, parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking), suicidality, mania, psychosis, amnesia, or related symptoms. The accepted study designs comprised clinical trials, cohort studies, cross-sectional and case-control studies, meta-analyses, retrospective reviews, pharmacovigilance studies, and systematic or narrative literature reviews. Only studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 2010 and 2025 were considered. Studies exclusively evaluating benzodiazepines, those involving non-human subjects, abstract-only records without full texts, and opinion pieces like editorials, commentaries, or protocols lacking patient-level data were excluded. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across databases including PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (limited to the first 200 hits) to identify relevant articles published between 2010 and 2025. In addition to journal publications, pharmacovigilance and regulatory safety reports cited in the included articles were also examined. The last search update was performed on May 30, 2025.

Search strategy

We employed a comprehensive search strategy using Boolean operators and controlled vocabulary (e. g., Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] terms) where applicable. A sample of the final search string used in PubMed is shown below:

(“zolpidem” OR “zopiclone” OR “eszopiclone” OR “zaleplon” OR “suvorexant”) AND (“neuropsychiatric adverse effects” OR “hallucinations” OR “mania” OR “psychosis” OR “parasomnia excluding sleepwalking” OR “suicidal ideation” OR “falls” OR “amnesia” OR “sleepwalking”) AND (“observational” OR “RCT” OR “randomised controlled trial” OR “meta-analysis” OR “systematic review” OR “literature review” OR “pharmacovigilance report” OR “cohort”).

Two reviewers conducted the search independently and resolved discrepancies through discussion, in case of any disagreement the opinion of a third independent reviewer was taken.

Selection process

All identified records were screened through a two-stage process using Microsoft Excel 365. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were reviewed to identify potentially relevant studies. In the second stage, full texts of eligible articles were assessed thoroughly to confirm inclusion based on the predefined criteria. Any disagreements during the selection process were resolved through discussion and consensus, or by involving a third reviewer when necessary. The entire screening and selection process was documented using a PRISMA 2020-compliant flowchart to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Data collection process

A standardized data extraction form was designed and pilot-tested prior to the full data extraction process. For each study included in the review, information such as citation details (including authors and year), study design and setting, the specific sedative-hypnotic drug(s) assessed, descriptions of neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and relevant patient characteristics were systematically recorded. Two reviewers independently extracted the data using Microsoft Excel 365 to ensure accuracy and consistency. Any discrepancies in the extracted information were addressed through discussion and consensus, with the involvement of a third reviewer if needed.

Data items

The primary data item extracted was the presence and specific nature of neuropsychiatric adverse effects associated with newer sedative-hypnotic medications. In addition to identifying these adverse outcomes, secondary data elements were also collected to provide contextual insight. These included patient-level risk factors such as pre-existing psychiatric history, advanced age, or patterns of inappropriate or off-label use that may predispose individuals to adverse reactions. Furthermore, drug-specific adverse event profiles were noted for example, parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking) frequently reported with zolpidem and incidences of sleepwalking particularly associated with suvorexant.

Synthesis of results

A qualitative synthesis approach was adopted to analyze the extracted data. The data were thematically categorized based on drug class, the type and frequency of reported neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs), drug-wise distribution of ADRs, and identification of high-risk patient populations. These thematic categories were then visually represented using stacked bar charts and standard bar graphs to illustrate patterns such as ADR types associated with specific drugs and the prevalence of ADRs in high-risk groups. Narrative summaries were constructed to interpret these trends and provide contextual understanding across the included literature. Additionally, a separate data matrix was employed to catalogue background and thematic synthesis studies that contributed to the discussion, although these were not included in the core qualitative dataset.

RESULTS

A total of 20 unique records were retrieved through structured database searches and supplementary hand-searching. After the removal of duplicates and an initial eligibility screening of titles and abstracts, 13 full-text studies were assessed for inclusion. Of these, 9 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the core qualitative synthesis.

Seven studies were excluded for reasons such as sole focus on benzodiazepines, insufficient neuropsychiatric outcome data, or irretrievable full text. The full study selection process is summarized according to PRISMA guidelines in the table 1 below.

Table 1: PRISMA flow summary

| Stage of screening | Number of studies |

| Records identified through search | 20 |

| Records screened (titles/abstracts) | 20 |

| Full-text articles assessed for eligibility | 13 |

| Studies included in qualitative synthesis | 9 |

| Studies excluded | 4 |

Overvie of included studies

The 9 studies selected for core synthesis spanned various methodologies, including pharmacovigilance analyses, retrospective cohort studies, observational studies, systematic review, meta-analysis and randomized controlled trial. These studies explored the neuropsychiatric safety profiles of newer sedative-hypnotic drugs: zolpidem, zopiclone, eszopiclone, suvorexant, and zaleplon (table 2).

Most commnly reported neuropsychiatric ADRs

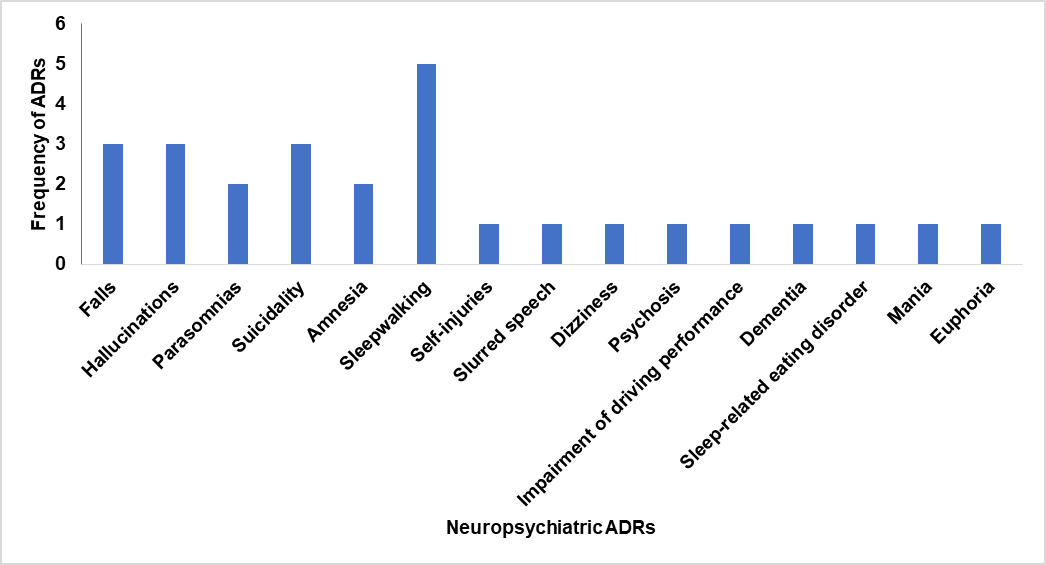

Among the nine studies reviewed, sleepwalking was the most frequently reported neuropsychiatric adverse drug reaction (ADR), cited in five studies. Hallucinations, suicidality, and falls followed closely, each noted in three studies. These ADRs were primarily associated with Z-drugs, especially zolpidem, suggesting a consistent pattern across different populations and study designs.

Less common but notable ADRs such as amnesia, parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking), psychosis, and sleep-related eating disorder were also observed, highlighting the broad psychiatric profile of these medications (table 3 and fig. 1). These findings underscore the importance of careful pharmacovigilance, particularly in psychiatric and elderly cohorts, where such effects may be underreported or misattributed.

Table 2: Summary of included core studies

| Study (Year) | Drugs studied | Setting/Design | Key population | Primary ADRs identified |

| Wong et al. (2017) [3] | Zolpidem | US Pharmacovigilance (FAERS) | General users | Hallucinations, parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking), suicidality |

| Harbourt et al. (2020) [4] | Z-drugs (Zolpidem, Zaleplon, Eszopiclone) | FAERS+Literature Case Review | Adults on hypnotics | Falls, suicidality, self-injuries |

| Ben‐Hamou et al. (2011) [13] | Zolpidem | Pharmacovigilance (Australia) | Mixed users (Adults and elderly) | Hallucinations, amnesia, parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking), suicidality |

| Schuelter-Trevisol et al. (2025) [14] | Zolpidem | Retrospective cohort | Brazilian general population | Amnesia, sleepwalking |

| Ceccherini-Nelli et al. (2021) [8] | Zopiclone | Retrospective psychiatric review (chart review of inpatients) | Violent or difficult-to-treat psychiatric inpatients | Sleepwalking, slurred speech |

| Kate et al. (2015) [2] | Z-drugs | Narrative/literature review | Elderly psychiatric patients | Sleepwalking, dizziness, falls, psychosis, impairment of driving performance, dementia |

| Hatta et al. (2024) [9] | Suvorexant | Randomized Controlled Trial | Hospitalized elderly patients | Falls, hallucination, sleepwalking |

| Mittal et al. (2021) [6] | Zolpidem | Systematic review | Patients presenting with zolpidem-induced complex sleep behaviours | Sleepwalking, sleep-related eating disorder |

| Sabe et al. (2019) [5] | Zolpidem | Systematic review | Psychiatric population | Mania, euphoria |

Table 3: Frequency of neuropsychiatric ADRs across all studies

| Neuropsychiatric ADRs | Frequency of ADRs | References |

| Falls | 3 | [2, 4, 9] |

| Hallucinations | 3 | [3, 9, 13] |

| Parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking) | 2 | [3, 13] |

| Suicidality | 3 | [3, 4, 13] |

| Amnesia | 2 | [13, 14] |

| Sleepwalking | 5 | [2, 6, 8, 9, 14] |

| Self-injuries | 1 | [4] |

| Slurred speech | 1 | [8] |

| Dizziness | 1 | [2] |

| Psychosis | 1 | [2] |

| Impairment of driving performance | 1 | [2] |

| Dementia | 1 | [2] |

| Sleep-related eating disorder | 1 | [6] |

| Mania | 1 | [5] |

| Euphoria | 1 | [5] |

| Total ADRs | 27 |

ADR distribution by drug

The table 4 highlights that Z-drugs (zolpidem, zaleplon, zopiclone, eszopiclone) are consistently associated with a wider range of neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs), including hallucinations, suicidal ideation, and sleepwalking. In contrast, suvorexant showed fewer positive associations, suggesting a potentially safer neuropsychiatric profile or underreporting (table 4). These differences underscore the need for careful drug selection based on individual psychiatric risk.

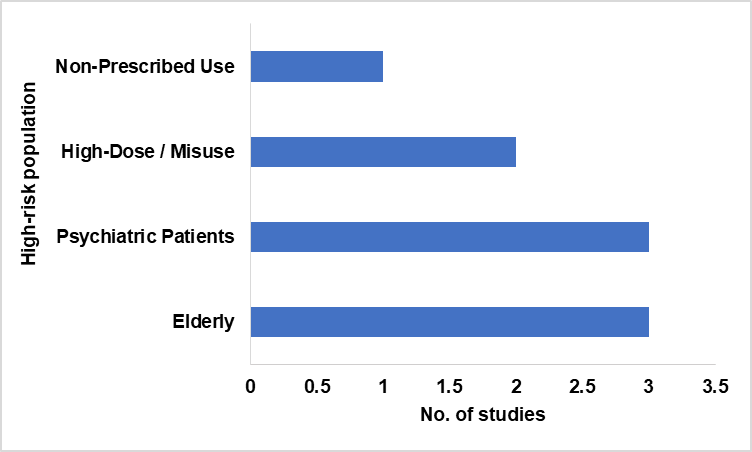

High-risk populations identified

From the studies included, the elderly and psychiatric populations were consistently identified as the most at-risk groups for experiencing neuropsychiatric ADRs (table 5 and fig. 1). The use of sedative-hypnotics in these groups often coincided with comorbid conditions, polypharmacy, and altered brain sensitivity to psychoactive agents.

Thematic synthesis of ADR patterns

Across the nine core studies with extractable ADR data [2-6, 8, 9, 13, 14], five major neuropsychiatric themes emerged: disordered nocturnal behaviours (sleepwalking [2, 8, 9, 6, 14] and parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking) [3, 13] were most frequently reported; perceptual and cognitive disruptions, such as hallucinations [3, 9, 13] and amnesia [13, 14], also appeared consistently; mood and behavioural dysregulation, including suicidality [3, 4, 13], self-injury [4], mania, and euphoria [5], were present primarily in psychiatric cohorts; motor and physical impairments notably falls [2, 4, 9], slurred speech [8], and impaired driving [2] were common in elderly groups; and finally, isolated neurocognitive deterioration including psychosis and dementia was reported [2]. These ADRs were predominantly associated with Z-drugs, whereas suvorexant showed fewer reported effects.

Fig. 1: Frequency of neuropsychiatric ADRs across all studies

Table 4: Neuropsychiatric ADRs by drug class

| ADR | Z-drugs (zolpidem/zaleplon/zopiclone/eszopiclone) | Suvorexant |

| Hallucinations | P [3, 13] | P [9] |

| Parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking) | P [3, 13] | A |

| Falls | P[2, 4] | P [9] |

| Suicidal Ideation | P [3, 4, 13] | A |

| Amnesia | P [13, 14] | A |

| Sleepwalking | P [2, 6, 8, 14] | P [9] |

| Self-injuries | P [4] | A |

| Slurred speech | P [8] | A |

| Dizziness | P [2] | A |

| Psychosis | P [2] | A |

| Impairment of driving performance | P [2] | A |

| Dementia | P [2] | A |

| Sleep-related eating disorder | P [6] | A |

| Mania | P [5] | A |

| Euphoria | P [5] | A |

*A=Absent; P=Present

Table 5: High-risk groups

| High-risk population | No. of studies | Supporting studies |

| Elderly | 3 | [2, 9, 13] |

| Psychiatric Patients | 3 | [2, 5, 8] |

| High-Dose/Misuse | 2 | [14] |

| Non-Prescribed Use | 1 | [14] |

Fig. 2: High-risk group

DISCUSSION

The pattern of neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions (ADRs) linked to non-benzodiazepine hypnotics observed in this review is consistent with broader pharmacological literature. Zolpidem, zopiclone, and eszopiclone were all frequently associated with disordered sleep behaviours, perceptual disturbances, and affective dysregulation. Sleepwalking, hallucinations, falls, and suicidality were among the most commonly reported effects. These outcomes were corroborated by real-world pharmacovigilance data from Borchert et al., who observed that zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone had the highest ADR reporting rates in both clinical databases and patient-generated narratives [15].

In a population-based cohort study, Richardson et al. reported that Z-drugs significantly increased the risk of sleep disturbances and fall-related injuries among people living with dementia, underscoring the vulnerability of elderly populations to neurocognitive toxicity from these agents [16]. A particularly noteworthy concern involves individuals with underlying neurological conditions, such as those recovering from traumatic brain injury (TBI), who appear to be especially susceptible to paradoxical neuropsychiatric reactions. Seenivasan et al. reviewed the neurophysiological mechanisms of sleep–wake disturbances post-TBI and noted that agents like zolpidem can aggravate cognitive dysregulation and even trigger behavioural disinhibition due to altered GABAergic signalling in the injured brain [17]. This aligns with your review’s observation that non-standard neurological baselines, such as abnormal EEGs or brain injuries, can predispose patients to heightened neuropsychiatric sensitivity when exposed to hypnotics, particularly Z-drugs.

These risks were not limited to cognitively impaired groups; in a meta-analysis, Glass et al. found that hypnotic use, including zolpidem and zopiclone, was associated with a significant increase in motor vehicle collisions due to impaired psychomotor performance and residual sedation, reinforcing the concern that Z-drugs may interfere with normal waking function [18].

Suvorexant, by contrast, exhibited a different neuropsychiatric ADR profile. As a dual orexin receptor antagonist, it is known to have a more targeted effect on the sleep–wake cycle and avoids the global gamma-aminobutyric acid-A (GABA-A) receptor potentiation that characterises Z-drugs. A randomised controlled trial by Michelson et al. found that suvorexant was not significantly associated with increased rates of hallucinations, parasomnias (excluding sleepwalking), or suicidality compared to placebo, although somnolence was still prevalent [19]. This aligns with the relatively milder ADR profile found in our review for suvorexant, supporting its use in patients for whom neuropsychiatric tolerability is a clinical priority.

Similarly, Hoque et al. reported that zolpidem use in older adults was independently associated with increased risk of somnambulism, sleep-related eating disorder and sleep talking, possibly mediated by disruption of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and serotonergic pathways [20].

Though not devoid of side effects, the orexin-targeting mechanism may afford a greater neuropsychiatric safety margin, particularly in patients with psychiatric histories. The increasing trend of prescribing sedative-hypnotics such as alprazolam and zolpidem in non-psychiatric departments, including general medicine and surgery, highlights the potential for off-label use and consequent neuropsychiatric risks in populations not routinely monitored for such effects [21]. Polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing of sedative-hypnotics, particularly benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, have been frequently reported in psychiatric outpatient populations, raising concerns about increased risks of neuropsychiatric adverse outcomes and treatment non-adherence [22]. Recent pharmaceutical advancements have demonstrated the efficacy of sustained-release and solid dispersion formulations of zolpidem tartrate in improving sleep maintenance, enhancing solubility, and increasing oral bioavailability. While these innovations may contribute to reduced dosing frequency and improved therapeutic outcomes, they simultaneously raise critical concerns about altered pharmacokinetic profiles and the possible modulation of neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions, especially in elderly or psychiatric populations [23, 24]. The importance of active pharmacovigilance in detecting central nervous system-related adverse drug reactions, especially with psychotropic and sedative-hypnotic medications, has been emphasized in hospital-based surveillance studies, reinforcing the need for close clinical monitoring of neuropsychiatric symptoms during therapy [25].

One of the key strengths of this systematic review lies in its comprehensive and methodologically rigorous approach. It followed PRISMA guidelines to ensure a structured and transparent screening process, drawing from multiple databases and including a hand-search to reduce the risk of missing relevant studies. The inclusion of a diverse range of study designs, such as pharmacovigilance reports, retrospective cohorts, systematic reviews, and randomised controlled trials, allowed for a multi-faceted understanding of the neuropsychiatric adverse effects associated with sedative-hypnotics. Furthermore, the review effectively identified high-risk populations and synthesised findings not just quantitatively, but also thematically, offering clinically meaningful insights that extend beyond numerical trends.

Despite its strengths, this review is not without limitations. The heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of outcome definitions, ADR reporting formats, and study populations made it difficult to conduct any form of meta-analysis or derive pooled estimates. In addition, a number of potentially relevant studies had to be excluded due to unavailability of full texts or lack of extractable ADR data, which may have introduced a degree of selection bias. The reliance on secondary data sources such as pharmacovigilance databases, which are subject to underreporting and variable reporting quality, may also have affected the completeness of ADR representation. Lastly, studies in languages other than English were excluded, which may have limited the global generalisability of the findings.

To build on the insights provided by this review, future research should prioritise well-designed prospective studies that directly compare different classes of hypnotics, particularly Z-drugs and orexin receptor antagonists, using standardised ADR definitions. Longitudinal studies in elderly and psychiatric populations could help clarify causality and identify predictors of neuropsychiatric susceptibility. It would also be valuable to integrate neuroimaging or neurophysiological data in future work to explore the biological mechanisms underpinning these adverse effects. Moreover, expanding research to include non-English language studies and underrepresented populations would help provide a more comprehensive and globally relevant evidence base for safer hypnotic prescribing practices.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review has highlighted the breadth and complexity of neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions associated with commonly used sedative-hypnotics, particularly the Z-drugs and suvorexant. While these medications are often prescribed to address sleep disturbances, their potential to induce serious cognitive, behavioural, and mood-related side effects, especially in vulnerable groups such as the elderly and those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions, should not be underestimated. The findings underscore the importance of cautious prescribing, close monitoring, and the need for personalised approaches that weigh both therapeutic benefits and neuropsychiatric risks. Suvorexant appears to offer a comparatively safer profile, but further long-term studies are needed to substantiate its advantages. Ultimately, improving awareness among clinicians, patients, and policymakers about these risks is essential to ensuring safer pharmacological management of insomnia and related disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the support of open-access academic resources, pharmacovigilance databases, and institutional library access that enabled the comprehensive search and full-text retrieval of studies included in this review.

FUNDING

This research was conducted without any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No external financial support was received for the design, data extraction, analysis, or writing of this systematic review.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was conceptualized by Pranab Das, who also carried out the literature search, gathered pertinent information, assisted with the creation of the manuscript and statistical analysis, and offered general supervision and direction during the whole research process, including the interpretation of the results. Daradi Das supported the paper drafting process and helped with the data extraction and literature search. Rohit Tigga helped with the results' interpretation and statistical analysis. Daradi Das helped resolve conflicts during data extraction, participated in the research selection process, and critically evaluated the text for quality, rigor, and clarity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002 Apr;6(2):97-111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186, PMID 12531146.

Kate N, Parkar S, Pawar S, Sawant N. Adverse drug reactions due to antipsychotics and sedative hypnotics in the elderly. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2015;2(1):16-29. doi: 10.4103/2348-9995.161377.

Wong CK, Marshall NS, Grunstein RR, Ho SS, Fois RA, Hibbs DE. Spontaneous adverse event reports associated with zolpidem in the United States 2003-2012. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Feb 15;13(2):223-34. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6452, PMID 27784418, PMCID PMC5263078.

Harbourt K, Nevo ON, Zhang R, Chan V, Croteau D. Association of eszopiclone zaleplon or zolpidem with complex sleep behaviors resulting in serious injuries, including death. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020 Jun;29(6):684-91. doi: 10.1002/pds.5004, PMID 32323442.

Sabe M, Kashef H, Gironi C, Sentissi O. Zolpidem stimulant effect: induced mania case report and systematic review of cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019 Aug 30;94:109643. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109643, PMID 31071363.

Mittal N, Mittal R, Gupta MC. Zolpidem for insomnia: a double edged sword a systematic literature review on zolpidem induced complex sleep behaviors. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021 Sep;43(5):373-81. doi: 10.1177/0253717621992372, PMID 34584301, PMCID PMC8450729.

Schuelter Trevisol F, Cipriano Felippe F, Camargo B, Schuelter Trevisol B, Raimundo LJ, Trevisol DJ. Incidence of adverse effects and misuse of zolpidem. J Pharm Technol. 2025 Mar 14:87551225251324856. doi: 10.1177/87551225251324856, PMID 40092895.

Ceccherini Nelli A, Bucuci E, Burback L, Li D, Alikouzehgaran M, Latif Z. Retrospective observational study of daytime add on administration of zopiclone to difficult-to-treat psychiatric inpatients with unpredictable aggressive behavior with or without EEG dysrhythmia. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 17;12:693788. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.693788, PMID 34483989, PMCID PMC8415882.

Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, Takeuchi T, Taira T, Uemura K. Suvorexant for reduction of delirium in older adults after hospitalization: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Aug 1;7(8):e2427691. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27691, PMID 39150711, PMCID PMC11329875.

Yin L, LV G, Han R, Zhang Y, Du X, Song Y. Effectiveness and safety of suvorexant in preventing delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Que. 2024;1(3):138-47. doi: 10.69854/jcq.2024.0017.

Sadahiro R, Hatta K, Yamaguchi T, Masanori E, Matsuda Y, Ogawa A. A multi-centre double-blind, randomized placebo controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of ramelteon for the prevention of postoperative delirium in elderly cancer patients: a study protocol for JORTC-PON2/J-SUPPORT2103/NCCH2103. Japan J Clin Oncol. 2023 Aug 30;53(9):851-7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyad061, PMID 37340766, PMCID PMC10473272.

Beaucage Charron J, Rinfret J, Coveney R, Williamson D. Melatonin and ramelteon for the treatment of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2023 Jul;170:111345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111345, PMID 37150157.

Ben Hamou MO, Marshall NS, Grunstein RR, Saini B, Fois RA. Spontaneous adverse event reports associated with zolpidem in Australia 2001-2008. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(4):559-68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00919.x, PMID 21481053.

Schuelter Trevisol F, Cipriano Felippe F, Camargo B, Schuelter Trevisol B, Raimundo LJ, Trevisol DJ. Incidence of adverse effects and misuse of zolpidem. J Pharm Technol. 2025 Mar 14:87551225251324856. doi: 10.1177/87551225251324856, PMID 40092895, PMCID PMC11909643.

Borchert JS, Wang B, Ramzanali M, Stein AB, Malaiyandi LM, Dineley KE. Adverse events due to insomnia drugs reported in a regulatory database and online patient reviews: comparative study. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Nov 8;21(11):e13371. doi: 10.2196/13371, PMID 31702558, PMCID PMC6874799.

Richardson K, Loke YK, Fox C, Maidment I, Howard R, Steel N. Adverse effects of Z-drugs for sleep disturbance in people living with dementia: a population-based cohort study. BMC Med. 2020 Nov 24;18(1):351. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01821-5, PMID 33228664, PMCID PMC7683259.

Seenivasan S, Kiley D, Kile M, Werner JK. Sleep wake disorders after traumatic brain injury: pathophysiology, clinical management and future. Semin Neurol. 2025;45(3):383-400. doi: 10.1055/a-2605-8706, PMID 40570859.

Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005 Nov 19;331(7526):1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47, PMID 16284208, PMCID PMC1285093.

Michelson D, Snyder E, Paradis E, Chengan Liu M, Snavely DB, Hutzelmann J. Safety and efficacy of suvorexant during 1-y treatment of insomnia with subsequent abrupt treatment discontinuation: a phase 3 randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014 May;13(5):461-71. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70053-5, PMID 24680372.

Hoque R, Chesson AL Jr. Zolpidem-induced sleepwalking sleep related eating disorder and sleep driving: fluorine-18-flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography analysis and a literature review of other unexpected clinical effects of zolpidem. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009 Oct 15;5(5):471-6. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.27605, PMID 19961034, PMCID PMC2762721.

Sebastian A, Pk A, Areeckal J, Davis S. A prospective study on drug utilization pattern of antidepressants in non-psychiatric departments in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12(3):224-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i3.30004.

Sabu L, Yacob M, Mamatha K, Singh H. Drug utilization pattern of psychotropic drugs in psychiatric outpatient department in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(1):259-61. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i1.15112.

Sri AR, KL. Formulation and evaluation of zolpidem tartrate layered tablets by melt granulation technique for treatment of insomnia. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(6):139. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i6.21540.

Ahmed AB, Das G. Effect of menthol on the transdermal permeation of aceclofenac from microemulsion formulation. Int J App Pharm. 2019;11(2):117-22. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2019v11i2.30988.

James J, Rani J. A prospective study of adverse drug reactions in a tertiary care hospital in South India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2020 Jan;13(1):89-92. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2020.v13i1.36028.