Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 9, 47-51Original Article

STUDIES ON BASIL SEED MUCILAGE FOR PHARMACEUTICAL APPLICATION

SUTAPA BISWAS MAJEE*, RACHAYEETA BERA

Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, NSHM Knowledge Campus, Kolkata, 60, B l Saha Road, Kolkata-700053, West Bengal, India

*Corresponding author: Sutapa Biswas Majee; *Email: sutapabiswas2001@yahoo.co.in

Received: 13 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 28 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) is a versatile and traditional medicinal plant renowned for its potential to treat various diseases. Basil seeds constitute a promising alternative in designing pharmaceutical preparations owing to their ability to produce a mucilaginous gel in water. The objective of the present study is to investigate the change in skin hydration and hemocompatibility following pharmaceutical applications of basil seed mucilage.

Methods: The study aims at hydrothermal extraction of basil seed mucilage from seeds, studies on its specific physicochemical parameters, hemocompatibility, and investigation on rat skin hydration by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic analysis.

Results: The outcome of the study exhibited that basil seeds produced 11 to 13% mucilage with an aqueous solubility of 97.23 ± 0.5% (*P<0.01) and swelling capacity of 31.51±0.43 ml/g (*P<0.05) in 6 h, indicating superior skin moisturizing property. FTIR spectroscopic analysis of the mucilage proposed hydrogen bond formation, presence of amide groups of proteins, uronic acid, and pyranose sugar. The hemocompatible mucilage (2000µg/ml) demonstrated a potent anti-inflammatory effect (194.53±7.78 %), showcasing its promise for topical application. Skin hydration studies in rats confirmed significant improvement in skin moisture with 1% w/v mucilage gel.

Conclusion: Therefore, basil seed mucilage exhibited possibilities for pharmaceutical application and skin hydration in animals, offering a safe, natural, and better alternative.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, Basil seed mucilage, FTIR spectroscopy, Skin hydration, Swelling capacity

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i9.55574 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Natural polymers are gaining popularity over synthetic ones because of their biocompatibility, ease of biodegradation, and non-toxic potential. Mucilages are plant-derived heteropolysaccharides that constitute a three-dimensional, reticulate gel-like structure [1]. The monosaccharide composition is vital in governing the functional aspects of the mucilaginous hydrocolloid [2, 3]. Basil(Ocimum basilicum), a member of the family Lamiaceae, is an invaluable medicinal resource for its multifarious activities in digestion, stomachache, stress, microbial infections, inflammation, fever, urinary problems, brain, and heart functioning [4, 5]. Basil seeds, however, represent an underexplored but promising, eco-friendly alternative in altering the pharmaceutical attributes. The testa and pericarp of basil seeds swell in water to produce a thick layer of adherent acidic polysaccharide-and fibre-rich polyelectrolyte mucilaginous gel around them, which is responsible for the exhibited diverse range of properties. The varying content of glucose, galactose, mannose, uronic acid, xylan, arabinose, rhamnose, glucomannan, and glucan in the mucilage may account for its benefits [6]. However, the extraction method and carbohydrate analysis procedure may produce variation in the monosaccharide percentages of the mucilage. The proportion of fats and oils may also vary in the mucilage [4]. Incorporation of non-toxic and biodegradable mucilaginous hydrocolloids in pharmaceutical formulations provides swelling, water-retention, shear-thinning behaviour, and emulsification properties as emulsion stabilizers with their appropriate morphological and rheological characteristics [2, 7].

Basil seed mucilage (BSM) is being investigated for its broader uses in the pharmaceutical and nutritional fields as a super disintegrant for fast-dissolving tablets, oral delivery agent for BCS Class II and Class IV drugs, mucoadhesive controlled release polymer, potential wound dressing with zinc oxide nanofibers, probiotic agent, rheological enhancer for low-fat milk and low-fat mozzarella cheese [1, 2, 4, 5, 8-12]. Basil seed mucilage hydrogel sponge has demonstrated non-cytotoxicity and non-allergenicity, enabling localized cosmetic or therapeutic delivery, respectively [1].

The characteristics of basil seed mucilage may be explored for pharmaceutical applications, thus expanding its diverse uses. The objective of the present study is to investigate eco-friendly, easily extractable basil seed mucilage (R-C1) for its hemocompatibility assay and skin hydration potential with Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic analysis, which has not been evaluated previously. FTIR investigations are essential for the study of alteration in hydrophilic components of skin due to the hydrophilic and swellable basil seed mucilage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Basil seeds were purchased from Yuvika Herbs (India), cleaned, dried, and stored in air-tight containers for future use. All other reagents were purchased from E. Merck (India) Ltd.

Animal selection was based on the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, NSHM Knowledge Campus, Kolkata, No NCPT/IAEC-019/2025.

Mucilage extraction

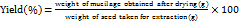

The dried plant specimen was authenticated by the Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India, Shibpur, Howrah, Kolkata. Basil seed mucilage (BSM) was extracted by hydrothermal method with continuous stirring (REMI, RQ-121, India) of basil seeds in distilled water (1:50 w/v) at 40–60 °C for 3 h. Extracted white mucilage was separated from the swollen seeds using mesh 10, dried at 40 °C for 12 h, pulverized into a fine mucilage powder by passing through an 80-mesh screen, and stored for future use [13]. The yield for each experimental run was obtained in triplicate. The percentage yield of extracted BSM was calculated using Equation 1 [14].

……. (1)

……. (1)

Extraction efficiency was evaluated by re-extracting the residual seeds from the initial extraction stage using the same seed-to-water ratio and calculating the percentage yield [15].

pH determination

The pH of a fully hydrated 1% w/v aqueous dispersion of BSM was measured using a digital glass electrode pH meter (Hanna Instruments, USA) [16].

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic (FTIR) characterization

FTIR spectroscopy was performed to identify the different functional groups in the extracted BSM. A powdered sample of mucilage was blended with potassium bromide and compressed to form a pellet. The FTIR spectrum of the sample pellet was obtained with a FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, ALPHA T) in the spectral range of 4000–500 cm-1 [17-19].

Solubility determination

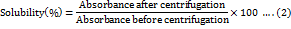

Qualitative analysis of BSM solubility was estimated in non-aqueous solvents like ethanol, methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetone, and chloroform. For quantitative estimation of aqueous solubility, the solubility of BSM (%) was determined by stirring an aqueous mucilaginous dispersion (2 mg/ml) to ensure complete dispersion, followed by centrifugation (REMI Instruments, India) at 3000 rpm for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm before and after centrifugation [20]. The solubility percentage of BSM was determined by Equation 2.

Least gelation concentration

The least gelation concentration (LGC) was measured to determine the minimum concentration of BSM necessary to form a stable gel. Different concentrations (0.5-2.5%w/v) of BSM and xanthan gum (reference) aqueous dispersions were heated to 80-90 °C, and cooled down to 25 °C. The gel formation was assessed by inverting the test tubes frequently within 1h, and the concentration at which no flow occurred was recorded as the LGC [17].

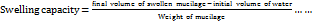

Swelling capacity

An aqueous dispersion of BSM (0.25% w/v) was prepared in a measuring cylinder. The initial volume was recorded and allowed to stand undisturbed at 25 °C, noting the volume every hour, and continued till a constant value was obtained. The final swollen mucilage volume was recorded in triplicate. The swelling capacity was calculated using the formula given [21]:

(3)

(3)

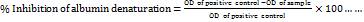

Determination of anti-inflammatory activity

The in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of aqueous dispersions of BSM (500 and 2000 µg/ml) was measured by the egg albumin denaturation assay. Diclofenac sodium was used as a positive control. For the reaction, 2 ml of the sample, 0.2 ml of fresh egg albumin, and 2.8 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 6.4) were mixed. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min after vortexing, heated at 70 °C for 5 min, and cooled to 25 °C for measurement of absorbances at 660 nm by UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1900i, Japan) [22]. The anti-inflammatory activity of the mucilage was measured in triplicate by Equation 4.

(4)

(4)

Hemocompatibility assay

The hemocompatibility assay of BSM was conducted using goat blood collected from a recently slaughtered animal from an enlisted meat vendor. The mucilaginous dispersion (2 ml) (2000 µg/ml) was poured into the dialysis bag (MWCO 12000-14000Da) (Himedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India), immersed in 0.9% w/v normal saline, and kept in a BOD incubator (Lab Solution, India) for 30 min at 37 °C. Finally, the mucilage leachate was mixed with diluted goat blood and adjusted with normal saline. The solutions, 0.1N HCl and normal saline, were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The sample and controls were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and centrifuged at 3000 rpm. The absorbances were measured using the UV-VIS spectrophotometer at 415 nm [23].

……. (5)

……. (5)

Skin hydration study

Three male Wistar albino rats (Naaz Pet Shop, Kolkata) (180-200 g) were used in the study. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Approval No NCPT/IAEC-019/2025). The epidermis of the dorsal surface of rats was clean-shaven by non-aggressive depilation with a razor. One animal was used as a control, and the other two as test (BSM) groups (0.5 and 1% w/v). A constant, well-defined quantity of the aqueous mucilaginous dispersion (1g) was applied to the rats marked test. Excess gel was removed from the skin. After 3h, the animals were anesthetized with brief ether inhalation and killed by cervical dislocation. Skin hydration status and gain in water content of the rat stratum corneum were investigated using excised dorsal rat skin by attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. The dorsal hairless skin was excised into uniform pieces (2.5 cm X 2.5 cm) for the control group and BSM groups. The ATR-FTIR absorption bands of the excised skin were analyzed in the 4000-500 cm-1 wavenumber range (Bruker, ALPHA T). The advantage of the spectroscopic method is that any change in moisture content in the stratum corneum or its barrier properties due to application of the mucilage can be diagnosed and monitored. The skin “moisturizing factor”(MF) for the mucilage was determined, which is defined as the ratio of water content in amide I and amide II bands of the excised animal skin. Thus, the ATR-FTIR spectrum of skin provides a detectable “fingerprint” of the extent of hydration [24].

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean±standard error of mean (SEM) using the GraphPad Prism software (Prism 9.4.1) (GraphPad Software, USA) with P<0.05 at 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mucilage extraction

The plant specimen was authenticated as Ocimum basilicum L. as R-C1 by the Central National Herbarium, Howrah. The percentage yield of BSM extracted using the hydrothermal method at neutral pH and seed: water ratio of 1:50 varied from 11.2±1.7 to 13.1±0.96%, on a dry weight basis. The reported yield of the mucilage was approximately 10% at 40 °C, with an increase in temperature to 20% at 50-65 °C, whereas the yield varied from 12.75-16.8% by microwave-assisted extraction procedure. However, the yield percent was more than that of chia seeds. Effects of alteration in pH to a slightly alkaline value, extraction time, and force of agitation may play vital roles in determining the efficiency of mucilage production [12, 25-27]. But no additional mucilage could be recovered from the residual seeds using the same process, confirming 100% efficiency of the extraction process.

pH determination

The pH of a 1% w/v aqueous dispersion of BSM was estimated at 6.5±0.3-7.0±0.1 at 25 °C. In reported studies, the pH of BSM aqueous dispersion varied from 6.0 to 8.4 [28, 29]. The pH of the aqueous mucilage dispersion indicates excellent compatibility with the physiological pH of human skin, highlighting its potential as a safe and skin-friendly constituent in the development of pharmaceutical products.

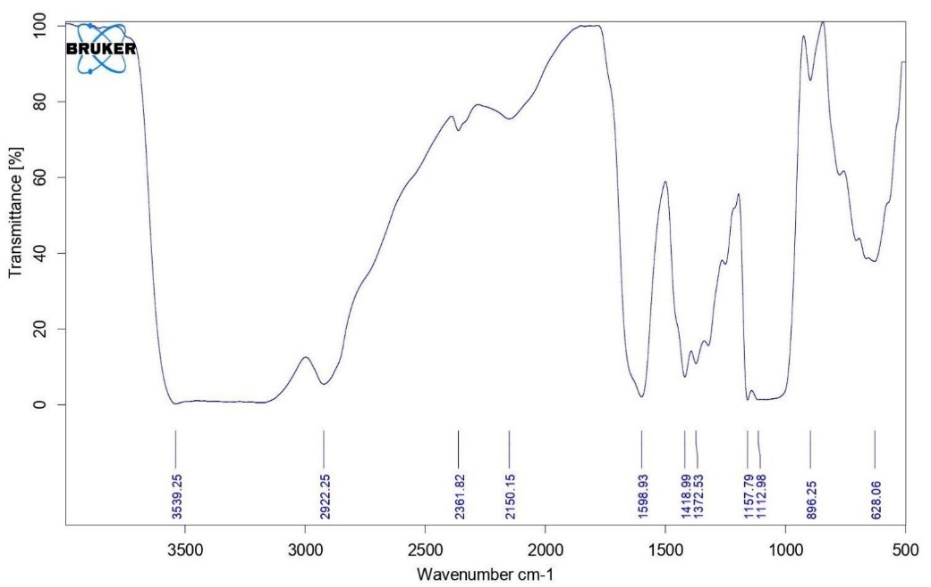

FTIR spectroscopic analysis

The FTIR spectrum of BSM (fig. 1) showed a broad peak at 3539.25 cm⁻¹ and a relatively sharp peak at 2922.25 cm⁻¹ attributed to-OH stretching due to the free, intra-or intermolecular hydrogen bonds of carboxylic acid and alcohol. Absorbance at 1598.93 cm-1is due to amide groups of proteins present in the molecule. Free carboxylate ions of uronic acid may have produced the peak at 1418.99 cm-1 due to symmetric and asymmetric C=O stretching. The peak at 1372.53 cm⁻¹ was linked to asymmetric stretching vibrations of alkane groups. Bands in the 1080–1270 cm⁻¹ region were characteristic of C–O stretching of saccharide unit, and the band at 896.25 cm-1 is due to the pyranose form of sugars [1, 2, 7, 27, 29, 30].

Fig. 1: FTIR spectrum of basil seed mucilage (BSM)

Solubility determination

Qualitative solubility studies of BSM show its insolubility in ethanol, methanol, chloroform, acetone, DMSO, and miscibility in water, forming a mucilaginous dispersion [29, 31]. The aqueous solubility of BSM was found to be 97.23 ± 0.5% (*P<0.01), exhibiting its superior solubility in water, which might be due to the monosaccharides present.

Least gelation concentration

BSM exhibited LGC at 1% w/v, with a gelation time of 3 min. However, xanthan gum showed a higher LGC of 2.5% w/v. This indicates an ability of BSM to form a superior non-flowing gelling network structure for use in skincare products. Its minimum gelation rate was comparatively better than that of chia seed mucilage. This might be attributed to the polysaccharide content of the basil seed mucilage [32].

Swelling capacity

BSM exhibited a swelling capacity of 31.51±0.43 ml/g in a maximum of 6 h at a concentration of 0.25% w/v(*P<0.05), indicating its superior skin moisturizing property. It demonstrated variable swelling behaviour at 24 and 48h in phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and water [33]. This pronounced swelling behaviour may be primarily attributed to intra-and intermolecular hydrogen bonds with water molecules, as observed with Hibiscus rosa-sinensis mucilage [34].

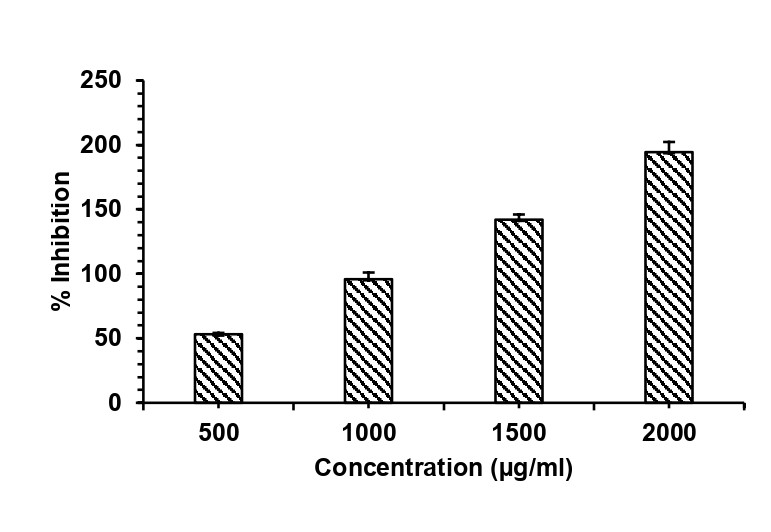

Determination of anti-inflammatory activity

Protein denaturation during inflammation can be inhibited by the administration of anti-inflammatory agents. The extent of heat-induced egg albumin denaturation reflects the anti-inflammatory potential of therapeutic agents. BSM exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of albumin denaturation (53.16±1.09 to 194.53±7.78 %) at concentrations ranging from 500-2000 μg/ml, suggesting that it possesses significant anti-inflammatory potential compared to standard diclofenac sodium at 1500 and 2000 μg/ml (fig. 4). Higher doses have been considered because of the intended topical use. Several phenolic, flavonoid, glycosidic, and terpenoid components of the mucilage and its ability to reduce the myeloperoxidase levels in a rat model with acetic acid-induced colitis might have contributed to the effect [35]. However, the ethanol and hexane extracts of basil seed mucilage demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity at significantly higher doses, in contrast to standard aspirin [36]. Similarly, Azadirachta indica nanohydrogel showed significant anti-inflammatory activity, probably due to the secondary metabolites present in the oil [37]. Leaf extracts of Pinus brutia and Cedrus libani were found to exhibit better anti-inflammatory potential than the same doses of diclofenac sodium [38].

Fig. 2: In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of basil seed mucilage at 4 different concentrations with diclofenac sodium as the control

Hemocompatibility assay

The hemolysis percentage of BSM was 4.6%. The value was close to that of the orally disintegrating films of okra mucilage or methanolic thyme extract [39, 40].

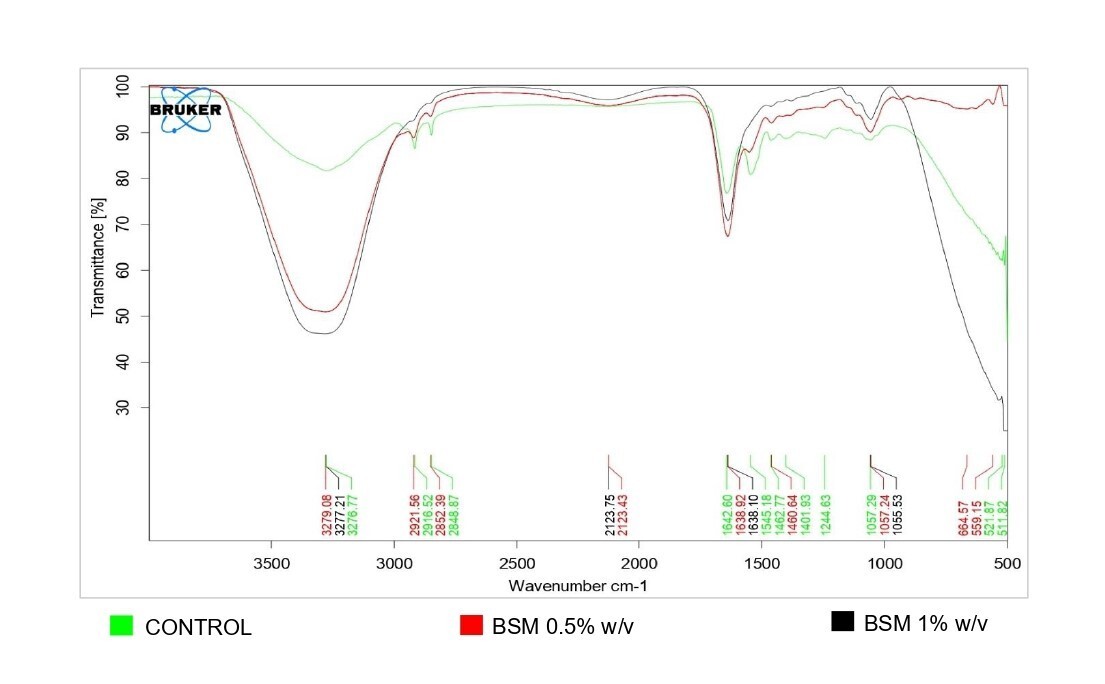

Skin hydration study

The O–H stretching peak observed around 3280 cm⁻¹ in FTIR spectra serves as a key measure of moisture content in the skin. However, the peak is affected by overlapping signals from amide bands and C–H asymmetric stretching of stratum corneum lipids. Therefore, it cannot be considered a specific marker for the hydration phenomenon. For a reliable assessment of skin hydration, the moisturizing factor (MF) or ratio of heights of amide I (1670-1620 cm⁻¹) to amide II (1560-1530 cm⁻¹) bands of skin should be considered, which provides a quantitative measurement of skin moisture. A higher amide band ratio with a higher value for the amide I band indicates a greater degree of skin hydration due to basil seed mucilage [24]. With BSM at 0.5% w/v, skin moisture was found to be 60 % at 3 h. BSM (1% w/v) showed an increase in moisture content to 98%, suggesting a corresponding rapid increase (fig. 3). The moisturizing factor also increased from 1.20 in control animal to 2.38 for test animal at 3h for BSM 1%w/v, indicating increased dryness of the control animal with time, and superior and sustained moisture content of the rat skin with higher BSM concentration. Thus, basil seed mucilage at 1%w/v exhibited potential for greater skin hydration in 3 h.

Fig. 3: FTIR spectrum of excised rat skin at 3 h, Control excised skin with no mucilage; Excised skin with 0.5% w/v BSM; Excised skin with 1%w/v BSM

CONCLUSION

The study highlights the significant potential of basil seed mucilage extract as a natural, skin-friendly pharmaceutical ingredient with low yield but superior swelling properties. The hydrothermal extraction at neutral pH has been utilized for producing the basil seed mucilage. The mucilage has been investigated for physicochemical parameters, skin hydration potential, in vitro anti-inflammatory activity, and hemocompatibility. BSM exhibited high water solubility and intense gelling capacity, making it suitable for pharmaceutical applications. FTIR spectroscopic analysis of the mucilage exhibited-OH stretching due to the hydrogen bonds of carboxylic acid, presence of amide groups of proteins, free carboxylate ions of uronic acid, and the sugar moiety. Skin hydration assessment by FTIR spectroscopy demonstrated a significant improvement in rat skin moisture content with 1% w/v BSM gel. The hemocompatible mucilage exhibited a marked in vitro anti-inflammatory potential. Therefore, basil seed mucilage may be considered suitable for topical pharmaceutical products, offering a natural, effective, biocompatible, and safe product. Basil seed mucilage thus, may contribute to its application in the pharmaceutical industry in the days ahead.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Dibyojyoti Banerjee acknowledged for his contribution in animal handling.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

SBM: Conceptualization and editing of manuscript; RB: Drafting of manuscript and experimentation

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Tantiwatcharothai S, Prachayawarakorn J. Characterization of an antibacterial wound dressing from basil seed (Ocimum basilicum L.) mucilage-ZnO nanocomposite. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019 Aug 15;135:133-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.118, PMID 31121236.

Naji Tabasi S, Razavi SM, Mohebbi M, Malaekeh Nikouei B. New studies on basil (Ocimum bacilicum L.) seed gum: part I fractionation physicochemical and surface activity characterization. Food Hydrocoll. 2016 Jan;52:350-8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.07.011.

Kusuma R, Samba Shiva Rao A. Application of Ipomoea batata starch mucilage as suspending agent in oseltamivir suspension. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2015 Oct 17;7(4):58-62.

Sayyad FJ, Sakhare SS. Isolation characterization and evaluation of Ocimum basilicum seed mucilage for tableting performance. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2018 Jan 29;80(2):282-90. doi: 10.4172/pharmaceutical-sciences.1000356.

Sakhare SS, Sayyad FJ. Design development and characterization of Ocimum basilicum mucilage based modified release mucoadhesive gastrospheres of carvedilol. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019 Sep 3;12(10):218-25. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i10.34291.

Nazir S, Wani IA. Fractionation and characterization of mucilage from basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seed. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants. 2022 Sep 1;31:100429. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmap.2022.100429.

Lee HY, Lee HJ, Ryu SH, Sim D, Kim DS. Development of eco-friendly and edible adhesive using basil seed mucilage. Appl Chem Eng. 2024 Jul 23;35(4):341-5. doi: 10.14478/ace.2024.1040.

Akhtar A, Araki T, Nei D, Khalid N. Formulation and characterisation of low-fat mozzarella cheese using basil seed mucilage: insights on microstructure and functional attributes. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2024 Apr 25;59(6):4134-43. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.17172.

Panda S, Suryawanshi M. Fabrication characterization and toxicity evaluation chemically cross linked polymeric material: a proof of concept. Scopus Indexed. 2023;16(3):6522-32. doi: 10.37285/ijpsn.2023.16.3.6.

Gupta MK, Priya S, Singh S, Verma S. Formulation and evaluations of mouth dissolving film using natural excipients. Int J Curr Pharm Rev Res. 2021;13(3):28-37.

Rahmati Joneidabad M, Alizadeh Behbahani B, Taki M, Hesarinejad MA, Toker OS. Active packaging coating based on Ocimum basilicum seed mucilage and probiotic Levilactobacillus brevis Lb13H: preparation characterization application and modeling the preservation of fresh strawberries fruit. Food Measure. 2025;19(2):994-1010. doi: 10.1007/s11694-024-03017-4.

Mallick MS, Roy A, Ray T, Shil A, Barik J, Koley T. Formulation and characterization of Ocimum basilicum seed and chitosan to fabricate mucoadhesive based nanoparticles via ionic gelation. Afr J Biomed Res. 2024 Nov 26;27 Suppl 4:3030-9. doi: 10.53555/AJBR.v27i4S.4143.

Naeeji N, Shahbazi Y, Shavisi N. In vitro antimicrobial effect of basil seed mucilage chitosan films containing Ziziphora clinopodioides essential oil and MgO nanoparticles. Nanomed Res J. 2020 Sep;5(3):225-33. doi: 10.22034/nmrj.2020.03.003.

Haile TG, Sibhat GG, Molla F. Physicochemical characterization of Grewia ferruginea Hochst. ex A. Rich. mucilage for potential use as a pharmaceutical excipient. BioMed Res Int. 2020 Jun 7;2020:4094350. doi: 10.1155/2020/4094350, PMID 32596305.

Mondal S, Chakrabarty K, Bose M, Maity S, Chowdhury SS, Das S. Exploring the therapeutic potential: in vitro assessment of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of methanolic extract from tabernaemontana divaricata leaves. JSFS. 2024;11(3)134:40. doi: 10.53555/sfs.v11i3.2405.

Neeharika B, Vijayalaxmi KG. Optimisation of clove basil and sweet basil seeds mucilages extraction for utilisation as functional ingredients. J Sci Ind Res. 2023 Sep 1;82(9):989-99. doi: 10.56042/jsir.v82i9.1937.

Seyyed Mohammad G. Generation of porous structure from basil seed mucilage via supercritical fluid assisted process for biomedical applications. Int J PharmSci Dev Res. 2015;3(1):30-5. doi: 10.17352/ijpsdr.000014.

Goh KK, Matia Merino L, Chiang JH, Quek R, Soh SJ, Lentle RG. The physico-chemical properties of chia seed polysaccharide and its microgel dispersion rheology. Carbohydr Polym. 2016 Sep 20;149:297-307. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.126, PMID 27261754.

Jiao W, Chen W, Mei Y, Yun Y, Wang B, Zhong Q. Effects of molecular weight and guluronic acid/mannuronic acid ratio on the rheological behavior and stabilizing property of sodium alginate. Molecules. 2019;24(23):4374. doi: 10.3390/molecules24234374, PMID 31795396.

Nazir S, Wani IA. Functional characterization of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seed mucilage. Bioact Carbohydr Diet Fibre. 2021 May;25:100261. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2021.100261.

Ang AM, Raman IC Jr. Characterization of mucilages from Abelmoschus Manihot Linn. Amaranthus spinosus Linn. and Talinum triangulare (Jacq.) Willd. leaves for pharmaceutical excipient application. AJBLS. 2019 May 21;8(1):16-24. doi: 10.5530/ajbls.2019.8.3.

Oh S, Kim DY. Characterization antioxidant activities and functional properties of mucilage extracted from Corchorus olitorius L. Polymers. 2022;14(12):2488. doi: 10.3390/polym14122488, PMID 35746064.

Mohanta B, Sen DJ, Mahanti B, Nayak AK. Extraction characterization haematocompatibility and antioxidant activity of linseed polysaccharide. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications. 2023 Jun;5:100321. doi: 10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100321.

Lucassen GW, Van Veen GN, Jansen JA. Band analysis of hydrated human skin stratum corneum attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectra in vivo. J Biomed Opt. 1998 Jul;3(3):267-80. doi: 10.1117/1.429890, PMID 23015080.

Nazir S, Wani IA, Masoodi FA. Extraction optimization of mucilage from basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seeds using response surface methodology. J Adv Res. 2017;8(3):235-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2017.01.003, PMID 28239494.

Nguyen Le D, Nguyen CT, Ton That Q, Tran TL, Tran Van H. Extraction and evaluation of lipid entrapment ability of Ocimum basilicum L. seed mucilage. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2021 Aug 16;55(3):880-7. doi: 10.5530/ijper.55.3.162.

Shiehnezhad M, Zarringhalami S, Malekjani N. Optimization of microwave assisted extraction of mucilage from Ocimum basilicum var. album (L.) seed. J Food Process Preserv. 2023;2023(1):1-15. doi: 10.1155/2023/5524621.

Naji Tabasi S, Razavi SM. Functional properties and applications of basil seed gum: an overview. Food Hydrocoll. 2017 Dec;73:313-25. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.07.007.

Maqsood H, Uroos M, Muazzam R, Naz S, Muhammad N. Extraction of basil seed mucilage using ionic liquid and preparation of AuNPs/mucilage nanocomposite for catalytic degradation of dye. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020 Dec 1;164:1847-57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.073, PMID 32791269.

Keisandokht S, Haddad N, Gariepy Y, Orsat V. Screening the microwave-assisted extraction of hydrocolloids from Ocimum basilicum L. seeds as a novel extraction technique compared with conventional heating stirring extraction. Food Hydrocoll. 2018 Jul;74:11-22. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.07.016.

Krishna A, Mohanan S. Formulation and evaluation of liquid oral suspension of paracetamol using newly isolated and characterized Hygrophila spinosa seed mucilage as suspending agent. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018 Nov 7;11(11):437-41. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i11.28856.

Guan L, Ma Y, Yu F, Jiang X, Jiang P, Zhang Y. The recent progress in the research of extraction and functional applications of basil seed gum. HeliyonHeliyon. 2023;9(9):e19302. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19302, PMID 37662748.

Tantiwatcharothaia S, Prachayawarakorn J. Property improvement of antibacterial wound dressing from basil seed (Ocimum basilicum L.) mucilage-ZnO nanocomposite by borax crosslinking. Carbohydr Polym. 2020 Jan 1;227:115360. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115360.

Yahaya NA, Anuar NK, Saidin NM. Hibiscus rosa-sinensis mucilage as a functional polymer in pharmaceutical applications: a review. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(1):44-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i1.46159.

Saeidi F, Sajjadi SE, Minaiyan M. Anti-inflammatory effect of Ocimum basilicum Linn. seeds hydroalcoholic extract and mucilage on acetic acid-induced colitis in rats. J Rep Pharma Sci. 2018 Jul;7(3):295-305. doi: 10.4103/2322-1232.254806.

Osei Akoto CO, Acheampong A, Boakye YD, Naazo AA, Adomah DH. Anti-inflammatory antioxidant and anthelmintic activities of Ocimum basilicum (sweet basil) fruits. J Chem. 2020 May 23;2020(1):1-9. doi: 10.1155/2020/2153534.

Kaur S, Sharma P, Bains A, Chawla P, Sridhar K, Sharma M. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of low energy assisted nanohydrogel of Azadirachta indica oil. Gels. 2022;8(7):434. doi: 10.3390/gels8070434, PMID 35877519.

Karrat L, Abajy MY, Nayal R. Investigating the anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of leaves ethanolic extracts of Cedruslibani and Pinusbrutia. HeliyonHeliyon. 2022;8(4):e09254. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09254, PMID 35434396.

Khatreja K, Santhiya D. Physicochemical characterization of novel okra mucilage/hyaluronic acid based oral disintegrating films for functional food applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Oct;278(1):134633. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134633, PMID 39128761.

Rafique S, Murtaza MA, Hafiz I, Ameer K, Qayyum MM, Yaqub S. Investigation of the antimicrobial antioxidant hemolytic and thrombolytic activities of Camellia sinensis Thymus vulgaris and Zanthoxylum armatum ethanolic and methanolic extracts. Food Sci Nutr. 2023;11(10):6303-11. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3569, PMID 37823136.