Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 11, 15-24Review Article

LEVERAGING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY: ADVANCES IN DRUG SYNTHESIS, DEVELOPMENT AND DESIGN

MANJIRI SHASTRI* , SIDDHANT RAUT

, SIDDHANT RAUT , VEDANT TAKALKAR

, VEDANT TAKALKAR , SWATI KSHIRSAGAR

, SWATI KSHIRSAGAR

JSPM’s Rajarshi Shahu College of Pharmacy and Research, Tathawade, Pune-411033, India

*Corresponding author: Manjiri Shastri; *Email: pranalkutkar@gmail.com

Received: 25 Jul 2025, Revised and Accepted: 13 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Artificial intelligence (AI) has transitioned from a prospective innovation to an integral component of current pharmaceutical research and development. The objective of the present review is to explore the study of recently developed AI techniques that focus on enhancing human intelligence functions rather than simply imitating them. With the help of AI and Robotics, the most desirable components of industry, such as increased productivity, consistency in product quality, and the production of goods including hazardous reactants without danger to workers' lives, can be achieved. AI in drug synthesis can be applied for automated reaction prediction, retrosynthesis planning, and process optimization. As for drug design, different AI models can be used for de novo drug design, ligand and structure-based and multi-target drug design. AI, in predictive modeling, can be used for quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, predictive toxicology, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) Profiling, and disease modeling. AI with robotics in the life of mankind has several advantages and disadvantages. Overall, AI-driven tools in drug synthesis, molecular design, and predictive modeling streamline the drug discovery process, enabling medicinal chemists to innovate more quickly and precisely. These applications help move from a trial-and-error approach to a data-driven one, ultimately bringing more effective therapies to market. The future is always hard to predict, but it will be determined by AI as it will become the next frontier in pharmacy. This review primarily focuses on the application of AI in Medicinal Chemistry, encompassing drug synthesis, development, and design.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Productivity, Synthesis, Development, Designing, Drug discovery

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i11.56256 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Medicinal chemistry is a multidisciplinary field at the intersection of chemistry, biology, and pharmacology, focusing on the discovery, design, and development of new therapeutic compounds. The primary goal of medicinal chemistry is to create and optimize molecules that can interact with biological systems to treat, cure, or prevent disease. This process involves identifying potential molecular targets, designing compounds that bind effectively to these targets, and refining these compounds to enhance their potency, selectivity, and safety profile. Medicinal chemists employ techniques from organic synthesis, computational modeling, and structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis to refine molecular designs and predict therapeutic outcomes [1, 2].

Medicinal chemistry has traditionally faced significant challenges, including prolonged development timelines, high costs, and the complexity of biological systems. However, the integration of AI offers transformative solutions to these longstanding issues. Automated screening and retrosynthesis planning can substantially reduce development time by accelerating compound identification and synthesis pathways. Studies show that AI can reduce drug discovery timelines by 30–40% and lower research and development (R and D) costs by approximately 15–20% [3]. Cost-efficiency can be achieved through data-driven decision-making and optimized resource allocation, enabling more strategic and targeted research efforts. Furthermore, machine learning models and AI-driven QSAR analysis provide deeper insights into the biological activities of compounds, enhancing predictive accuracy and facilitating the design of more effective therapeutic agents [4, 5]. However, not all AI-driven projects succeed; for example, Benevolent AI’s clinical trial failure involving its drug candidate BEN-2293 underscores the limitations of current methods. BEN-2293 was a topical pan-tyrosine receptor kinase (Trk) inhibitor developed for treating atopic dermatitis. While the drug was safe and well tolerated (meeting the primary endpoint), it failed in the phase 2a clinical trial on secondary endpoints as it did not improve eczema severity or itch compared to placebo [6, 7].

To compile this review, we performed an extensive literature search covering the period from around 2000 to 2025, using a diverse set of AI-related keywords across multiple academic and general search engines including PubMed, Scopus, Web of science, and Google scholar, to ensure an inclusive overview of AI applications in medicinal chemistry. In this article, we provide comprehensive review that explores the transformative role of AI in the field of medicinal chemistry, highlighting its diverse applications and the significant advancements, it brings to drug discovery, design, and development, and it provide insights into how AI is revolutionizing medicinal chemistry, highlighting the enhanced efficiency, accuracy, and innovation in drug discovery. In this article, we mention specific applications and case studies, which illustrate the potential for AI to address longstanding challenges. By considering both promises and limitations of AI in this field, we aim to offer a balanced perspective that will guide future endeavors.

Ai in drug synthesis

In the last few years, the use of AI in solving problems related to organic chemistry has achieved a great feat in constructing highly accurate predictive models by data-driven technologies. AI algorithms make use of digital data to make new predictions in computers by encoding chemical rules. For instance, by encoding computers with known chemical reactions, we can allow them to predict the outcomes of new chemical reactions with high accuracy. Four of the main factors that have contributed to the rise of data-driven methods in the field of organic chemistry are algorithmic developments, availability of large data sets, and accessibility to larger computational resources. The emerging methods range from the prediction of a chemical reaction to chemical reactivity prediction, from retrosynthesis to reaction condition optimization, all the way to yield predictions. The development of a new drug is a very complex, expensive, and long process that typically costs 2.6 billion USD and takes 12 years on average [3, 8].

Reaction prediction

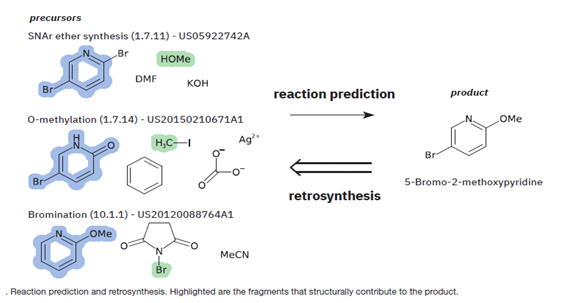

Prediction of chemical reaction outcomes is fundamental knowledge and the basis of modern chemistry. The reason why automation of reaction prediction with the help of computer algorithms or AI became popular was that the product determination of simple reactions sometimes proved to be a problem for an expert with decades of experience in synthetic chemistry. But in the case of more complex reactions, the prediction of outcome was quite challenging as the nature of reactants, reagents, and physical conditions strongly affected the formation of one product or another. Fig. 1 illustrates an example of reaction prediction alongside retrosynthesis.

Fig. 1: Reaction prediction and retrosynthesis [9]

Until today, reaction prediction by computer-based methods has been based on two systems, viz. rule-based expert systems and quantum mechanics-based systems [9, 10].

Rule-based expert systems

Early computer programs used rule-based systems with hand-coded graph rearrangements to represent chemical reactions abstractly. One pioneering system, computer-assisted mechanistic evaluation of organic reactions (CAMEO), evaluated reaction mechanisms by identifying electrophilic and nucleophilic centers, enabling product prediction from given reactants and conditions. A modern system belonging to the rule-based systems is Chematica, also known as Synthia. Synthia contains about 85,000 encoded reaction templates, offering high accuracy for reaction prediction and retrosynthesis. Its limitation is that any new entries should not conflict with the pre-existing rules. Also, the reaction prediction is based on overall reaction transformation, and a single step is not taken into consideration.

Quantum mechanics-based systems

Quantum mechanics-based systems are theoretical methods to handle the problem of reaction prediction. These systems rely on the position of electrons in the orbitals of different atoms. These methods are only applicable to smaller systems.

Retrosynthesis

Self-improved retrosynthetic planning

Retrosynthetic planning, in organic chemistry, is a process used to determine the sequence of a chemical reaction that can synthesize a target molecule from simpler starting materials. Unlike forward synthesis, which predicts the result of certain chemicals, retrosynthesis works in reverse, breaking down the target molecule step-by-step into more manageable and commercially available compounds. Recently developed algorithms have shown promising results in solving this problem of retrosynthesis by the use of deep neural networks (DNN). The main idea behind a new framework based on self-improved retrosynthetic planning is to train a backward reaction model to imitate success routes found by the retrosynthetic planning algorithm combined with it. The augmentation scheme diversifies training by generating new reactions with a forward model, effectively guiding the backward model to produce realistic, executable reactions. Future work may improve the filtering of unrealistic samples and enhance reaction augmentation [10].

AI-based retrosynthesis tools

IBM RXN for chemistry

IBM's RXN for chemistry uses neural machine translation models to predict chemical reactions and assist in retrosynthesis planning. It leverages sequence-to-sequence models similar to those used in language translation, making it effective in proposing synthetic routes for various organic compounds [11].

Synthia (Chematica)

Synthia is retrosynthesis software that combines a knowledge-based expert system with algorithms that simulate organic reactions. Synthia's system integrates a vast database of reactions and AI algorithms to generate synthetic pathways that optimize for cost, availability of reagents, and yield [12].

ASKCOS (Ask for cosmos)

ASKCOS is an open-source tool that applies machine learning and predictive analytics for retrosynthetic analysis. It utilizes both rule-based and machine-learning models for predicting reaction pathways and has integrated reaction feasibility scoring to aid in route selection [13].

Monte carlo tree search (MCTS)

Many search algorithms like MCTS, A* Search, and Retro* have made significant progress in the field of computer-aided retrosynthesis [14, 15].

MCTS exploration enhanced A* (MEEA*) search constitutes a hybridized algorithm that integrates the exploratory framework of MCTS with the systematic optimization of A* search. MCTS operates iteratively through a structured sequence of four procedural phases. The process begins with selection, where the algorithm navigates from the root node to a terminal leaf node using a probabilistic exploration policy to guide the traversal. In the expansion phase, the search tree is augmented by adding candidate child nodes that are considered promising, typically based on a single-step retrosynthetic expansion strategy. This is followed by evaluation, where a quantitative score is assigned to the terminal leaf node using either rapid rollout techniques or heuristic-based value estimation models. Finally, in the update phase, the evaluations obtained from the simulation are propagated backward through all intermediate states along the traversed path, refining the decision-making process for future iterations. A* search simultaneously manages two distinct sets of states: the OPEN set, encompassing nodes that have been generated but remain unexplored, and the CLOSED set, comprising nodes that have already undergone exploration. At the algorithm's inception, the CLOSED set is initialized as empty, while the OPEN set contains exclusively the root state [14, 16].

Benchmark studies have shown that algorithms like MCTS and A* achieve approximately 70–80% success in route prediction, which is comparable but not consistently superior to expert chemists. These methods also come with high computational costs, limiting their routine use in large-scale discovery campaigns. Furthermore, retrosynthesis tools such as Synthia and ASKCOS still struggle with stereochemistry handling and novel scaffolds, reflecting gaps that require further refinement [16].

Ai in drug development

The role of AI in drug development has been immense. AI helps in drug development in the following fields.

Lead identification and optimization

Leads are chemical or natural compounds that show biological activity against potential drug targets. Retrieval of drugs can be done from literature, computational and experimental analysis, etc. After the retrieval of lead, computational techniques like virtual screening help in the identification of the lead.

The identified lead is then chemically optimized through combinatorial chemistry and computer-aided drug design (CADD) techniques to improve its biological properties and drug-like properties to make it a drug for human consumption [17]. Fig. 2 depicts the two approaches: Lead identification and lead optimization.

Fig. 2: Lead identification and lead optimization approaches, Source: Created by the author using power point presentation

Deep learning-based molecular generation models are revolutionizing drug discovery by accelerating lead optimization, a critical step in refining molecules into drug candidates. These methods are classified into two categories: goal-directed and structure-directed. While goal-directed approaches are extensively studied, structure-directed optimization focuses on tasks such as fragment replacement, linker design, scaffold hopping, and side-chain decoration, which remain underexplored. The motivations, data strategies, and advancements in these tasks are categorized using classical optimization frameworks. Additionally, a practical protocol is proposed for experimental chemists to effectively utilize generative AI (GenAI) tools for structural modifications, bridging methodological advancements with practical applications [18].

Virtual screening

Structure-based virtual screening represents a pivotal methodology in the preliminary stages of drug discovery, garnering increasing attention for its application in the evaluation of multi-billion-scale chemical compound libraries. The efficacy of virtual screening, however, is fundamentally contingent upon the precision of computational docking in predicting both the molecular binding conformation (binding pose) and the thermodynamic binding affinity. Virtual screening is a CADD technique used to screen through a large number of leads to select compounds and rank them accordingly based on the binding energy or match score. The top-ranked compounds are further chosen carefully for testing in the lab. Virtual screening helps identify and select a lead in a short time and uses fewer resources. Software/tools available for VS include: PyRx, Auto DockVina, Discovery Studio, DOCK Blaster, iGemDock, etc. [17, 19].

Kannan et al. prepared derivatives of the diosmetin in ACD ChemSketch software and performed rapid virtual screenings of these compounds in the docking tool iGEMDOCK v2.0 and showed that these drug candidates have been validated through all in silico methods and have been proven to have excellent inhibitory effect against FimH of uropathogenic E. coli with good drug-like properties. Such studies prove the beneficial role of AI tools [20].

QSAR modeling

QSAR models are tools that use math and statistics to predict how the structure of a chemical relates to its biological activity. These models are widely used in fields like chemistry, biology, and toxicology. In drug discovery, QSAR is especially valuable, helping scientists predict if a new chemical will work well as a drug or could cause harmful effects. QSAR models allow researchers to screen chemicals early in the drug discovery process to rule out those that don't meet the requirements, which save time and resources. Beyond the pharmaceutical industry, QSAR is also becoming important for regulatory agencies that assess the safety of chemicals for people and the environment.

QSAR modeling generally involves three steps: (1) collect or, if possible, design a training set of chemicals; (2) choose descriptors that can properly relate chemical structure to biological activity; and (3) apply statistical methods that correlate changes in structure with changes in biological activity [21].

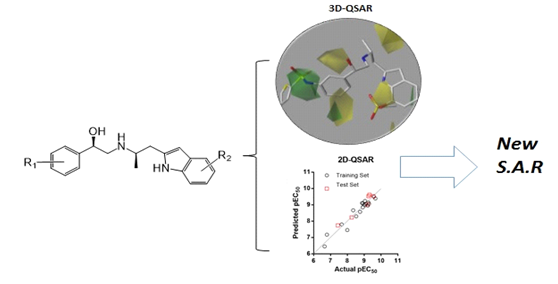

Most of the software products used in toxicity prediction, carcinogenicity prediction and skin sensitization prediction like CASE/Multicase (Multicase, Beachwood, OH, USA)[22, 23], TOPKAT (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA)[24], COREPA[25], etc. employ algorithms based on either 2D or 3D structure fragments that produce a qualitative prediction. Fig. 3 shows the Schematic Workflow of three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D‑QSAR) field maps (steric/electrostatic) and two-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (2D‑QSAR) activity prediction to derive new SARs.

Fig. 3: Schematic workflow: Integrating 3D‑QSAR field maps (steric/electrostatic) and 2D‑QSAR activity prediction to derive new SARs [26]

2D QSAR

The study of physicochemical properties and their effects on biological activity and toxicity began in the 19th century. Over time, scientists recognized the need to consider additional molecular factors for accurate predictions, leading to the development of QSAR models. These models relate a chemical's molecular structure to its biological activity using a range of molecular descriptors [27]. Early approaches, like the Hansch method, relied on parameters such as the octanol-water partition coefficient (log P) to predict properties like toxicity and binding interactions [28, 29]. Today, QSAR methods use both experimentally and computationally derived descriptors, categorized into types such as two-dimensional (2D), three dimensional (3D), and physicochemical.

2D QSAR models rely on simpler descriptors that use a molecule's 2D structure. These descriptors include constitutional (like atom counts), topological (molecular connectivity), and physicochemical properties (like log P). By contrast, 3D descriptors require molecular geometry and encode spatial aspects of the molecule. Modern QSAR approaches have shifted toward using computational descriptors generated by software, allowing for extensive screening of chemical libraries.

Variable selection in QSAR models is essential for model accuracy. Techniques like genetic algorithms (GA) [30] and k-nearest neighbor (kNN) [31] are popular for selecting relevant descriptors. Fragment-based QSAR [32] approaches, such as the free-Wilson method, estimate properties based on molecular fragments and are useful for screening large numbers of chemicals quickly. Hologram QSAR (HQSAR) is a novel 2D QSAR method that encodes structural fragments into molecular holograms, allowing for rapid and reproducible chemical prioritization. Overall, 2D QSAR remains a powerful tool in drug discovery and toxicology for efficiently predicting the effects of chemicals [33].

3D QSAR

3D-QSAR methods analyze and predict biological activity by focusing on spatial features of chemical compounds. Unlike 2D-QSAR, which relies on two-dimensional molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR models use three-dimensional spatial data. This shift allows researchers to align molecular structures in 3D space, enhancing predictions of activity based on spatially-dependent interactions like steric and electrostatic fields [34].

One prominent 3D-QSAR method is comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA). CoMFA measures variations in steric (related to the shape and volume) and electrostatic (related to charge distribution) fields across a 3D grid around aligned molecules, correlating these variations with biological activity. The quality of these models highly depends on molecular alignment, where knowledge of a molecule’s binding mechanism with a receptor can guide accurate structural superimpositions [35-37].

For scenarios where alignment is challenging, techniques like comparative molecular moment analysis (CoMMA) avoid alignment by using moment descriptors to summarize the 3D shape and charge distribution. However, such alignment-free methods often struggle with accuracy for certain symmetrical molecules [38].

In CoMFA, descriptors based on Lennard-Jones [39] and Coulomb potentials estimate steric and electrostatic interactions, respectively. Other 3D-QSAR methods, such as comparative molecular similarity indices analysis (CoMSIA) [40], introduce gaussian-based descriptors that also account for hydrophobicity and hydrogen bonding, allowing for comparisons even when molecules have varied sizesor shapes. Despite some limitations, 3D-QSAR models, particularly CoMFA and CoMSIA, have become valuable tools in drug discovery, offering insights into receptor-ligand interactions and enabling the design of biologically active compounds.

3D-QSAR models are highly sensitive to molecular alignment, which serves as the foundation for comparing steric and electrostatic fields across compounds. Unlike 2D-QSAR, where descriptors are fixed and alignment-independent, 3D-QSAR inputs are derived from spatially aligned molecules-making the process inherently error-prone. Misalignment introduces noise that can distort contour maps, reduce predictive accuracy, and lead to misleading interpretations of structure–activity relationships. The study shows that “the majority of the signal is in the alignments, so you need to get that right. If your alignments are incorrect, your model will have limited or no predictive power” [41].

To mitigate this, atomic-based alignment algorithms and receptor-guided approaches have been shown to produce more consistent and reliable models. Furthermore, platforms like cloud 3D-QSAR and AI-based approaches like graph neural networks (GNNs), integrate alignment and field computation to streamline the modeling process, improve robustness and accuracy [42, 43].

Predictive toxicology and ADMET analysis

The rapid growth of in silico drug discovery is fueled by extensive chemical repositories, advanced algorithms, and enhanced computational power. Methods such as high-throughput molecular docking (HTMD), structure-based virtual screening, and generative AI have enabled the screening of billions of molecules [44]. However, many identified hits lack drug-like properties, highlighting the need for effective screening of ADMET characteristics to identify promising therapeutic candidates [45].

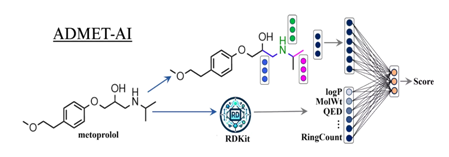

To address this need, ADMET-AI was developed as a fast, accurate platform for ADMET property prediction, featuring both a web interface and a python package. It utilizes Chemprop-RDKit, a graph neural network trained on 41 datasets from the therapeutics data commons (TDC), surpassing existing tools in speed and accuracy. Fig. 4 shows ADMET-AI uses machine learning models with the chemprop-RDKit architecture.

Fig. 4: ADMET-AI uses machine learning models with the chemprop-RDKit architecture. Chemprop-RDKit employs both a graph neural network (top) and 200 physicochemical properties computed by RDKit (bottom), which are combined by a feed-forward neural network (right) to predict the properties of a molecule [46]

ADMET-AI also offers unique features like local batch prediction and contextualized predictions against approved drugs, filling gaps in current ADMET prediction tools. The platform is open-source and freely available, aiming to enhance the evaluation of large chemical libraries for drug-like compounds.

Data for model development

Out of the 41 datasets that ADMET-AI uses, 21 form the TDC-ADMET Leaderboard. This enables the comparison of ADMET-AI with other ADMET models.

Model

ADMET-AI utilizes chemprop-RDKit, a deep learning architecture for ADMET prediction, combining a graph neural network (Chemprop) with 200 physicochemical features calculated using RDKit. Chemprop computes atom and bond features, aggregates them via message passing, and builds a molecular representation. This representation is concatenated with RDKit features and passed through feed-forward neural layers to predict ADMET endpoints.

Each dataset is modeled with five train/validation/test splits, and ensemble averaging across these splits improves robustness and accuracy by mitigating biases in individual models. Additionally, ADMET-AI uses a reference set of 2,579 regulatory-approved drugs from the drug bank, enabling percentile-based contextual ADMET predictions for queried molecules. The platform also supports filtering the reference set by anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) codes to align predictions with specific therapeutic contexts, recognizing that different drug classes have distinct ADMET requirements [47, 48].

Case studies

1) INS018_055 by in silico medicine: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a highly aggressive form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), characterized by chronic, progressive fibrosis, worsening lung function, respiratory failure, and high mortality [49]. Serine/threonine kinase-TRAF2 and NCK-interacting kinase (TNIK) are identified as an anti-fibrotic target by using predictive AI technology [50]. INS018_055 is an AI-designed inhibitor targeting fibrotic diseases. Developed using in silico medicine's generative AI platform, it progressed from discovery to phase II clinical trials in a remarkably short timeframe. This achievement underscores the potential of AI in expediting drug development processes. While this represents rapid AI-assisted discovery, its phase II results are unpublished, so clinical efficacy remains unproven. AI mainly contributed to target identification and lead optimization, whereas conventional preclinical and clinical validation protocols were still required [51].

2) DSP-0038 by Exscientia: DSP-0038 is an AI-designed serotonin receptor modulator developed through collaboration between Exscientia and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma. It functions as a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist and a 5-HT1A receptor agonist and is currently under investigation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease psychosis [52].

Ai in drug design

AI in drug design uses machine learning algorithms and computational models to predict drug potential, optimize molecular structure, and accelerate the drug discovery process. This technology can analyze vast amounts of biological and chemical data to identify compounds and predict their efficiency and safety, and also potentially reduce the time and cost of developing new medications [53].

Molecular modeling and structure prediction

AI leverages computational methods to simulate and predict the 3D structures of complex molecules, including proteins. AI algorithms can rapidly analyze large databases of molecular structures and properties, identify patterns, and make predictions about the 3D shapes and behavior of molecules, which is essential for drug discovery.

AI techniques like deep learning and reinforcement learning are being used to predict molecular structures and binding affinities. These AI models can analyze large datasets of molecular information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions about the 3D structures of molecules and how strongly they may bind to target proteins or receptors. This AI-powered approach has the potential to accelerate drug discovery and development by streamlining the process of identifying promising drug candidates.

The deep learning method possesses multiple hidden layers, and it is highly used for its flexibility to learn arbitrarily complex functions. Deep learning applies the back proportion algorithm and a gradient-based optimization method that allows neuronal network training, resulting in end-to-end differentiation. Fig. 5 shows a deep learning neural network with a multi-layered architecture.

Reinforcement learning approaches in molecular structure prediction aim to train AI models to predict the 3D structure of molecules and their binding affinity to target proteins. These models learn through a trial-and-error process, receiving rewards for accurately predicting molecular structures and binding interactions. By leveraging deep neural networks (DNN), reinforcement learning can capture the complex relationships between molecular features and structural outcomes, enabling more precise forecasting of biologically relevant molecular properties [54-56].

Fig. 5: Deep learning neural network with multi-layered architecture showing the input, output layer and multiple hidden layers [59]

Prediction of target protein structure

During drug development, assigning the correct molecular target is crucial to ensure treatment efficacy. Many proteins play roles in disease progression, and some are overexpressed under pathological conditions. To selectively target these disease-associated proteins, predicting their 3D structures is crucial, as it enables structure-based drug design tailored to the protein’s chemical environment. This strategy aids in assessing the likely effects and safety of drug candidates before synthesis. AI, particularly DNNs, has revolutionized structure prediction. A notable tool, AlphaFold, uses DNNs to predict protein structures by analyzing inter-residue distances and peptide bond angles. AlphaFold has achieved remarkable results, correctly predicting 25 out of 43 protein structures in benchmark tests.

In another study, AlQurashi applied a recurrent neural network (RNN)-based approach, developing a recurrent geometric network (RGN). This model included three stages-computation, geometry, and assessment. The primary amino acid sequence was encoded, and torsional angles for each residue were predicted using geometric information from earlier in the sequence. The network iteratively generated the protein backbone, ultimately outputting a 3D structure. The model's accuracy was assessed using the distance-based root mean square deviation (dRMSD), with optimization focused on minimizing this deviation. AlQurashi proposed that RGN would be faster than Alpha Fold, although AlphaFold was expected to outperform RGN in terms of accuracy for proteins with sequence homology to known structures.

Additionally, a study employed matrix laboratory (MATLAB) and a nonlinear, three-layered feed-forward neural network (NN) using supervised learning and a back propagation error algorithm to predict 2D protein structures. MATLAB was used to train both input and output datasets, with performance evaluated via NN metrics. The system achieved promising prediction accuracy, demonstrating the utility of traditional neural networks in simpler structural prediction tasks [54].

AI in drug-protein interaction and drug design

Drug–protein interactions have a vital role in the success of a therapy. The prediction of the interaction of a drug with a receptor or protein is essential to understanding its efficacy and effectiveness, allows the repurposing of drugs, and prevents polypharmacology. Various AI methods have been useful in the accurate prediction of ligand-protein interactions, ensuring better therapeutic efficacy. Wang et al. reported a model using the support vector machine (SVM) approach, trained on 15000 protein-ligand interactions, which were developed based on primary protein sequences and structural characteristics of small molecules to discover nine new compounds and their interaction with four crucial targets. Yu et al. exploited two random forest (RF) models to predict possible drug-protein interactions by the integration of pharmacological and chemical data and validating them against known platforms, such as SVM, with high sensitivity and specificity. Also, these modes were capable of predicting drug–target associations that could be further extended to target–disease and target–target associations, thereby speeding up the drug-discovery process. Xiao et al. adopted the Synthetic minority over-sampling technique and the neighborhood cleaning rule to obtain optimized data for the subsequent development of iDrugTarget. This is a combination of four sub-predictors (iDrug-GPCR, iDrug-Chl, iDrug-Enz, and iDrugNR) for identifying interactions between a drug and G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, enzymes, and nuclear receptors (NR), respectively. When this predictor was compared with existing predictors through target-jackknife tests, the former surpassed the latter in terms of both prediction accuracy and consistency. The ability of AI to predict drug-target interactions was also used to assist in the repurposing of existing drugs and avoiding polypharmacology. Repurposing an existing drug qualifies it directly for phase II clinical trials. This also reduces expenditure because relaunching an existing drug costs US$8.4 million compared with the launch of a new drug entity (US$41.3 million) [54].

De novo drug design

De novo drug design is the process of computationally generating novel chemical compounds that are predicted to have specific desired biological activities. Generative models like generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational auto encoders (VAEs) can be trained on large datasets of existing drug-like molecules to learn the underlying chemical patterns and rules. These models can then generate new, previously unseen molecular structures that are optimized to have the target pharmacological properties, accelerating the drug discovery process [57].

Generative models like GANs and VAEs can be used in de novo drug design to create novel chemical compounds with specific desired biological activities. These models learn the underlying patterns and distributions in existing drug-like molecules and then use that knowledge to generate new, previously unseen compounds that are predicted to have the target properties, such as binding to a particular protein target. The generative nature of these models allows them to explore a vast chemical space to discover novel lead compounds for drug development, accelerating the traditionally slow and expensive process of traditional drug discovery [57].

GANs are a type of generative model that utilizes two neural networks, a generator and a discriminator, that compete against each other. The generator tries to create realistic-looking samples, while the discriminator tries to distinguish the generated samples from real data. This adversarial training process allows GANs to learn to generate new data that closely resembles the training data, such as realistic-looking images, text, or other types of content.

VAE is a type of generative machine learning model that learns to encode data into a latent space representation, and then decode that representation back into the original data. The VAE is trained to generate new samples that are similar to the training data by learning the underlying probability distribution of the data [58].

Latent spaces in these generative models encode crucial chemical characteristics like scaffold topology, polarity, and lipophilicity. Although this makes it possible to explore a large amount of chemical space, many of the molecules that are produced are not feasible to synthesize. To make sure that suggested molecules are both novel and experimentally feasible, researchers are still working to integrate generative models with validation tools for retrosynthesis [60].

Case studies

1) EXS-21546 is a small-molecule drug candidate developed by the AI Company Exscientia for oncology applications. It is currently in clinical or paraclinical stages of development, meaning it has progressed from the initial AI-driven molecular design phase into early human trials or preclinical testing. EXS-21546 represents an example of how artificial intelligence can be used to accelerate the drug discovery process by designing novel drug molecules tailored for specific therapeutic targets [61].

2) DSP-1181, an AI-designed molecule developed with Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, entered clinical trials as a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist for obsessive-compulsive disorder. However, it was later discontinued, illustrating that attrition rates for AI-designed molecules remain comparable to those of conventionally developed drugs. Such examples highlight both the promise and limitations of AI in clinical translation [61].

Challenges and limitations

Data quality and availability

Data quality and availability are some of the biggest barriers to models that require a vast amount of high-quality and annotated data to learn meaningful patterns. However, the lack of comprehensive, high-quality datasets, particularly in pharmaceutical and biomedical domains, limits the ability of AI models to perform accurate predictions. The availability of diverse datasets, including clinical trials, medical imaging, and genomic data, is critical for training AI models [62].

Complexity of biological systems

AI has limitations in fully capturing the complexity of biological systems. Biological processes involve intricate interactions at the molecular, cellular, and organismal levels, which can be challenging to replicate comprehensively within the constraints of current AI frameworks. The inherent dynamism and context-dependent nature of biological phenomena pose challenges for AI models to account for the myriad of factors influencing these systems [62, 63].

Ethical and regulatory considerations

Regulatory and ethical concerns also pose challenges to the integration of AI in drug development. The pharmaceutical industry is heavily regulated, and AI models must comply with stringent regulations to ensure patient safety and drug efficacy. The food and drug administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have begun establishing frameworks for the approval of AI-based drug discovery tools. Specifically, the U. S. food and drug administration issued a draft guidance in January 2025-“Considerations for the use of AI to support regulatory decision-making for drug and biological products”-which outlines a risk-based credibility assessment framework for AI models intended to support regulatory decisions related to safety, efficacy, and quality of drugs [64]. In Europe, the EMA finalized its “Reflection paper on the use of AI in the medicinal product lifecycle” in September 2024, mandating a human-centric, risk-based approach for AI deployment across the entire drug lifecycle, including discoverability, clinical trials, manufacturing, and pharmacovigilance [65].

Despite these efforts, there remains no internationally harmonized standard, representing an unresolved challenge for the global adoption of pharmaceutical AI. Ethical concerns related to data privacy, algorithmic bias, and data security also need to be addressed. Bias in training data, for example, can lead to biased predictions, particularly in clinical trial recruitment or drug efficacy testing. Many historical clinical trial datasets are disproportionately composed of male participants, leading AI models trained on these data to perform less accurately in predicting drug efficacy or adverse events in women. Such an imbalance can compromise generalizability and patient safety. For example, Zolpidem (Ambien) in 2013. Such bias can have severe consequences for patient safety. Ensuring that AI systems are trained on diverse, representative datasets is essential for mitigating these risks [66].

The patentability of AI-generated models presents a complex challenge within current intellectual property frameworks, which are usually focused around human inventors. Most jurisdictions, including the United States, the European Union, India, and Australia require that a patent application name a natural person as the inventor [67].

This was notably affirmed in the case of Thaler v. USPTO, where the U. S. courts ruled that an AI system DABUS could not be recognized as an inventor under the Patent Act. Similarly, the European patent office rejected applications listing DABUS as the inventor, citing the European Patent Convention’s requirement for human inventorship [67, 68].

These decisions underscore the legal and philosophical tension between technological advancement and statutory interpretation. In India, section 3(k) of the Indian Patent Act excludes “computer programs per se” from patentability, further complicating the protection of AI-generated outputs unless they demonstrate a novel technical effect [69]. As AI continues to evolve, legal systems worldwide are being urged to reconsider the definition of inventorship and explore new models of attribution and ownership.

Future directions

Integration with quantum computing

AI models currently have limitations in fully capturing the complexity of biological systems. However, the combination of AI and quantum computing could lead to potential advances. Quantum computing can process information in a fundamentally different way than classical computers, which could enable AI models to better handle the vast amounts of data and intricate relationships inherent in biological systems. Potential advances arise when AI is combined with quantum computing, as quantum systems can leverage quantum phenomena like superposition and entanglement to perform certain computations exponentially faster than classical computers, potentially unlocking new insights into the fundamental mechanics of biological systems. Fundamentals of quantum computing involve the use of quantum-mechanical phenomena, such as superposition and entanglement, to perform computations. This paradigm shift from classical to quantum computing holds promise for advancing our understanding of complex biological processes in ways that classical AI alone cannot [70].

Precision medicine

AI plays a crucial role in the growth of personalized medicine, where the treatment is tailored to the genetic and molecular characteristics of individual patients. By analyzing the patient’s data, including the genetic profile, AI can help identify a subgroup of patients who may benefit from specific drug therapies. AI can also predict how a patient's genetics, lifestyle, and environment may influence their response to a particular drug, leading to more targeted and effective treatment strategies [61, 71].

CONCLUSION

AI is dignified to transform drug discovery and development, delivering extraordinary gains in speed, accuracy, and cost-efficiency. By leveraging advanced algorithms and data-driven insights, AI can significantly accelerate the journey from lab to market, reducing the time required to develop new therapies. Yet, despite its promise, several critical challenges remain. Issues such as inconsistent data quality, limited access to comprehensive datasets, opaque model decision-making, the intricate nature of biological systems, and the absence of standardized frameworks continue to hinder progress. Addressing these challenges is essential to fully realize AI’s potential in the pharmaceutical sector and to ensure its responsible, ethical, and safe integration into drug development workflows. Moving forward, the field must hold hybrid intelligence models, prioritize explainable AI, and foster collaborative ecosystems that bridge computational power with human-guided molecular insight. Only through such balanced evolution can AI truly fulfill its promise as a catalyst for scientific and therapeutic breakthroughs.

ABBREVIATIONS

AI: artificial intelligence; ADMET: absorption distribution metabolism excretion and toxicity; QSAR: quantitative structural activity relationship; SAR: structural activity and relationship; RandD: research and development; TNIK: Serine/threonine kinase-TRAF2 and NCK-Interacting Kinase; CAMEO: computer-assisted mechanistic evaluation of organic reactions; DNN: deep neural networks; CADD: computer aided drug design; GenAI: generative AI; log P: partition coefficient; 2D: two dimensional; 3D: three dimensional; GA: genetic algorithm; kNN: k-nearest neighbor; CoMFA: comparative molecular field analysis; CoMMA: comparative molecular moment analysis; CoMSIA: comparative molecular similarity indices analysis; HTMD: high throughput molecular docking; SVM: support vector machine; RF: random forest; GPCRs: G-protein coupled receptors; NR: nuclear receptors; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; RNN: recurrent neural network; RGN: recurrent geometric network; dRMSD: distance-based root mean square deviation; ATC: anatomical therapeutic chemical; GAN: generative adversarial networks; VAE: variational auto encoders; FDA: food and drug administration; EMA: European medicines agency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledged JSPM’s Rajarshi Shahu College of Pharmacy and Research, Tathawade, Pune, for providing facilities to conduct this study. We express our special thanks to Mr. Mandar Shastri for his graphic design support.

FUNDING

No funding was received for conducting this study.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Manjiri Shastri; Literature search: Siddhant Raut, Vedant Takalkar; Writing: Original Draft: Siddhant Raut, Vedant Takalkar; Reviewing, Editing, and Formatting: Manjiri Shastri, Swati Kshirsagar

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The Authors declared that they do not have any competing interests

REFERENCES

Medicinal chemistry. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/medicinal_chemistry. [Last accessed on 18 Aug 2025].

Fernandes JP. The importance of medicinal chemistry knowledge in the clinical pharmacist’s education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(2):6083. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6083, PMID 29606703.

Chan HC, Shan H, Dahoun T, Vogel H, Yuan S. Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019 Aug;40(8):592-604. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.06.004, PMID 31320117.

Long L, Li R, Zhang J. Artificial intelligence in retrosynthesis prediction and its applications in medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem. 2025;68(3):2333-55. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c02749, PMID 39883477.

Yang X, Wang Y, Byrne R, Schneider G, Yang S. Concepts of artificial intelligence for computer-assisted drug discovery. Chem Rev. 2019;119(18):10520-94. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00728, PMID 31294972.

Benevolent AI. Benevolent AI provides an update on its business priorities: workforce reduction of ~30% and closure of US office. London Benevolent AI; 2024 Apr 23. Available from: https://www.echemi.com/1840617.html. [Last accessed on 20 Aug 2025].

Benevolent AI. Benevolent AI’s cruel R and D: AI-enabled drug flunks mid-phase eczema trial to dent deal plans. Biotech Insider; 2023 May 26. Available from: https://biotech-insider.com/benevolentai-cruel-rd-ai-enabled-drug-flunks-midphase-eczema-trial-to-dent-deal-plans. [Last accessed on 20 Aug 2025].

Thakkar A, Johansson S, Jorner K, Buttar D, Reymond JL, Engkvist O. Artificial intelligence and automation in computer-aided synthesis planning. React Chem Eng. 2021;6(1):27-51. doi: 10.1039/D0RE00340A.

Kim J, Ahn S, Lee H, Shin J. Self-improved retrosynthetic planning. arXiv; 2021. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2106.04880.

Nair VH, Schwaller P, Laino T. Data-driven chemical reaction prediction and retrosynthesis. Chimia (Aarau). 2019 Dec;73(12):997-1000. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2019.997, PMID 31883550.

Schwaller P, Laino T, Gaudin T, Bolgar P, Hunter CA, Bekas C. Molecular transformer: a model for uncertainty calibrated chemical reaction prediction. ACS Cent Sci. 2019 Sep 25;5(9):1572-83. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00576, PMID 31572784.

Klucznik T, Mikulak Klucznik B, Mc Cormack MP, Lima H, Szymkuc S, Bhowmick M. Efficient syntheses of diverse medicinally relevant targets planned by computer and executed in the laboratory. Chem. 2018;4(3):522-32. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.02.002.

Coley CW, Thomas DA, Lummiss JA, Jaworski JN, Breen CP, Schultz V. A robotic platform for flow synthesis of organic compounds informed by AI planning. Science. 2019;365(6453):eaax1566. doi: 10.1126/science.aax1566.

Zhao D, Tu S, Xu L. Efficient retrosynthetic planning with MCTS exploration enhanced a search. Commun Chem. 2024 Mar;7(1):52. doi: 10.1038/s42004-024-01133-2, PMID 38454002.

Chen B, Li C, Dai H, Song L. Retro learning: retrosynthetic planning with neural guided A* search. arXiv. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2003.12725.

Struble TJ, Alvarez JC, Brown SP, Chytil M, Cisar J, DesJarlais RL. Current and future roles of artificial intelligence in medicinal chemistry synthesis. J Med Chem. 2020;63(16):8667-82. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02120, PMID 32243158.

Arya H, Coumar MS. Lead identification and optimization. In: The design & development of novel drugs and vaccines. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. p. 31-63. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-821471-8.00004-0.

Zhang O, Lin H, Zhang H, Zhao H, Huang Y, Hsieh CY. Deep lead optimization: leveraging generative AI for structural modification. J Am Chem Soc. 2024 Nov 5;146(46):31357-70. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c11686, PMID 39499822.

Zhou G, Rusnac DV, Park H, Canzani D, Nguyen HM, Stewart L. An artificial intelligence accelerated virtual screening platform for drug discovery. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7761. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52061-7, PMID 39237523.

Kannan I, Ishwarya K, Premavathi RK, Shantha S. Study on diosmetin derivatives as the inhibitors of Fim H of uropathogenic Escherichia coli by molecular docking with Hex. Int J Curr Pharm Rev Res. 2015;6(2):123-33.

Perkins R, Fang H, Tong W, Welsh WJ. Quantitative structure activity relationship methods: perspectives on drug discovery and toxicology. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2003 Aug;22(8):1666-79. doi: 10.1897/01-171, PMID 12924569.

Klopman G. Multicase 1. A hierarchical computer-automated structure evaluation program. Quant Struct Act Relat. 1992;11(2):176-84. doi: 10.1002/qsar.19920110208.

Rosenkranz HS, Klopman G. Structural basis of carcinogenicity in rodents of genotoxicants and non-genotoxicants. Mutat Res. 1990;228(2):105-24. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90067-e, PMID 2300064.

Prival MJ. Evaluation of the TOPKAT system for predicting the carcinogenicity of chemicals. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2001;37(1):55-69. doi: 10.1002/1098-2280(2001)37:1<55::aid-em1006>3.0.co;2-5, PMID 11170242.

Mekenyan O, Nikolova N, Schmieder P, Veith G. COREPA-M: a multi-dimensional formulation of COREPA. QSAR Comb Sci. 2004;23(1):5-18. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200330853.

Apablaza G, Montoya L, Morales Verdejo C, Mellado M, Cuellar M, Lagos CF. 2D-QSAR and 3D-QSAR/CoMSIA Studies on a Series of (R)-2-((2-(1H-Indol-2-yl)ethyl)amino)-1-Phenylethan-1-ol with human β₃-adrenergic activity. Molecules. 2017 Mar;22(3):404. doi: 10.3390/molecules22030404, PMID 28273884.

Lewis RA, Wood D. Modern 2D QSAR for drug discovery. WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 2014;4(6):505-22. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1187.

Jhanwar B, Sharma V, Singla RK, Shrivastava B. QSAR–hansch analysis and related approaches in drug design. Pharmacologyonline. 2011;1:306-44.

QSAR KH. Hansch analysis and related approaches. In: Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Press; 1993 Oct 28. Available from: https://download.e‑bookshelf.de/download/0000/6032/76/l‑G‑0000603276‑0002365071.pdf. [Last accessed on 16 Oct 2025].

Katoch S, Chauhan SS, Kumar V. A review on genetic algorithm: past present and future. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(5):8091-126. doi: 10.1007/s11042-020-10139-6, PMID 33162782.

Batista GE, Silva DF. How k-nearest neighbor parameters affect its performance; 2009.

Myint KZ, Xie XQ. Recent advances in fragment-based QSAR and multi-dimensional QSAR methods. Int J Mol Sci. 2010 Oct;11(10):3846-66. doi: 10.3390/ijms11103846, PMID 21152304.

Lowis DR. HQSAR: a new highly predictive QSAR technique. In: Proceedings of the first ECSOC conference; 1997. doi: 10.3390/ecsoc‑1‑02064.

Verma J, Khedkar VM, Coutinho EC. 3D-QSAR in drug design a review. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10(1):95-115. doi: 10.2174/156802610790232260, PMID 19929826.

Banerjee S, Baidya SK, Adhikari N, Jha T. 3D-QSAR studies: CoMFA, CoMSIA, and Topomer CoMFA methods. In: Current applications of pharmaceutical biotechnology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2023. doi: 10.1201/9781003303282‑3.

Sen S, Farooqui NA, Easwari TS, Roy B, CoMFA. 3D QSAR approach in drug design. J Pharm Res. 2012;5(5):2623-5.

Zhang L, Tsai KC, Du L, Fang H, Li M, Xu W. How to generate reliable and predictive CoMFA models. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(6):923-30. doi: 10.2174/092986711794927702, PMID 21182474.

Silverman BD, Platt DE. Comparative molecular moment analysis (CoMMA): 3D-QSAR without molecular superposition. J Med Chem. 1996 Mar;39(11):2129-40. doi: 10.1021/jm950589q, PMID 8667357.

Mittal RR, McKinnon RA, Sorich MJ. Effect of steric molecular field settings on CoMFA predictivity. J Mol Model. 2008;14(1):59-67. doi: 10.1007/s00894-007-0252-1, PMID 18038162.

Klebe G. Comparative molecular similarity indices analysis: CoMSIA. In: 3D QSAR in drug design; 1998. p. 87-104. doi: 10.1007/0‑306‑46858‑1_6.

Sippl W. 3D-QSAR–applications recent advances and limitations. In: Puzyn T, Leszczynski J, Cronin MT, editors. Recent advances in QSAR studies. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 103-25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9783-6_4.

Wang YL, Wang F, Shi XX, Jia CY, Wu FX, Hao GF. Cloud 3D-QSAR: a web tool for the development of quantitative structure activity relationship models in drug discovery. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(4):bbaa276. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa276, PMID 33140820.

Jiang D, Wu Z, Hsieh CY, Chen G, Liao B, Wang Z. Could graph neural networks learn better molecular representation for drug discovery? A comparison study of descriptor-based and graph-based models. J Cheminform. 2021;13(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13321-020-00479-8, PMID 33597034.

Lyu J, Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. Modeling the expansion of virtual screening libraries. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(6):712-8. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01234-w, PMID 36646956.

V Kalayil NV, D Souza SS, Khan SY, Paul P. Artificial intelligence in pharmacy drug design. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(4):21-7. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i4.43890.

Swanson K, Walther P, Leitz J, Mukherjee S, Wu JC, Shivnaraine RV. ADMET-AI: a machine learning ADMET platform for evaluation of large scale chemical libraries. Bioinformatics. 2024 Jul 1;40(7):btae416. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btae416, PMID 38913862.

Heid E, Greenman KP, Chung Y, Li SC, Graff DE, Vermeire FH. Chemprop: a machine learning package for chemical property prediction. J Chem Inf Model. 2024;64(1):9-17. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01250, PMID 38147829.

Landrum G. RDKit documentation release. RDKit Open‑Source Project; 2019 May 13. Available from: https://www.rdkit.org.

Barratt SL, Creamer A, Hayton C, Chaudhuri N. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): an overview. J Clin Med. 2018;7(8):201. doi: 10.3390/jcm7080201, PMID 30082599.

Ren F, Aliper A, Chen J, Zhao H, Rao S, Kuppe C. A small molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models. Nat Biotechnol. 2025 Jan;43(1):63-75. doi: 10.1038/s41587-024-02143-0, PMID 38459338.

Ren J. The grass roots mass power and biopolitics: the politicized pandemic in shanghai’s covid quarantine. Com. 2023;47(1):363-78. doi: 10.1353/com.2023.a911948.

Hessler G, Baringhaus KH. Artificial intelligence in drug design. Molecules. 2018 Oct;23(10):2520. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102520, PMID 30279331.

Sahu A, Mishra J, Kushwaha N. Artificial intelligence (AI) in drugs and pharmaceuticals. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2022;25(11):1818-37. doi: 10.2174/1386207325666211207153943, PMID 34875986.

Paul D, Sanap G, Shenoy S, Kalyane D, Kalia K, Tekade RK. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug Discov Today. 2021 Jan;26(1):80-93. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.10.010, PMID 33099022.

Duch W, Swaminathan K, Meller J. Artificial intelligence approaches for rational drug design and discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(14):1497-508. doi: 10.2174/138161207780765954, PMID 17504169.

Jing Y, Bian Y, Hu Z, Wang L, Xie XQ. Deep learning for drug design: an artificial intelligence paradigm for drug discovery in the big data era. AAPS J. 2018;20(3):58. doi: 10.1208/s12248-018-0210-0, PMID 29603063.

Gupta R, Srivastava D, Sahu M, Tiwari S, Ambasta RK, Kumar P. Artificial intelligence to deep learning: machine intelligence approach for drug discovery. Mol Divers. 2021;25(3):1315-60. doi: 10.1007/s11030-021-10217-3, PMID 33844136.

Zhang D, Han X, Deng C. Review on the research and practice of deep learning and reinforcement learning in smart grids. CSEE JPES. 2018;4(3):362-70. doi: 10.17775/CSEEJPES.2018.00520.

Selvaraj C, Chandra I, Singh SK. Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches for drug design: challenges and opportunities for the pharmaceutical industries. Mol Divers. 2022;26(3):1893-913. doi: 10.1007/s11030-021-10326-z, PMID 34686947.

Parrot M, Tajmouati H, Da Silva VB, Atwood BR, Fourcade R, Gaston Mathe Y. Integrating synthetic accessibility with AI-based generative drug design. J Cheminform. 2023;15(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13321-023-00742-8, PMID 37726842.

Exscientia Plc. Exscientia presents novel immuno-oncology biomarker for EXS-21546 at the ESMO I-O Annual Congress. In: Vienna and Oxford: Exscientiaplc; 2022 Dec 06. Available from: Websitehttps://investors.exscientia.ai/press‑releases/press‑release‑details/2022/exscientia‑presents‑novel‑immuno‑oncology‑biomarker‑for‑exs‑21546‑at‑the‑esmo‑i‑o‑annual‑congress/default.aspx. [Last accessed on 20 Aug 2025].

Vattikuti MC. Improving drug discovery and development using AI: opportunities and challenges. Res J (Research Gate). 2024;10(10):1-24.

Pasrija P, Jha P, Upadhyaya P, Khan MS, Chopra M. Machine learning and artificial intelligence: a paradigm shift in big data-driven drug design and discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2022 Oct;22(20):1692-727. doi: 10.2174/1568026622666220701091339, PMID 35786336.

U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Considerations for the use of artificial intelligence to support regulatory decision-making for drug and biological products. Draft guidance for industry and other interested parties. In: Silver Spring, MD: United States Food and Drug Administration; 2025 Jan 6. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/considerations-use-artificial-intelligence-support-regulatory-decision-making-drug-and-biological. [Last accessed on 21 Aug 2025].

European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the medicinal product lifecycle. EMA/CHMP/CVMP/83833/2023. Amsterdam, NLE: European Medicines Agency; 2024 Sep 9. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/system/files/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-use-artificial-intelligence-ai-medicinal-product-lifecycle-en.pdf. [Last accessed on 27 Aug 2025].

Gurung AB, Ali MA, Lee J, Farah MA, Al Anazi KM. An updated review of computer-aided drug design and its application to COVID-19. Bio Med Res Int. 2021;2021:8853056. doi: 10.1155/2021/8853056, PMID 34258282.

Nadjir KP, Lahari R, Nithyashree M, Manasa S, Shruthi MN. Patentability of AI-generated inventions: a comparative analysis of global patent law frameworks and their adaptation to artificial intelligence innovation. Int J Multidiscip Res (IJFMR). 2025 Jun 22;7(3). doi: 10.36948/ijfmr.2025.v07i03.48811.

Kretschmer M, Meletti B, Porangaba LH. Artificial intelligence and intellectual property: copyright and patents a response by the CREATe Centre to the UK Intellectual Property Office’s open consultation. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice. 2022;17(3):321-6. doi: 10.1093/jiplp/jpac013.

Ipleaders. Patentability of AI inventions; 2023. Available from: https://blog.ipleaders.in/patentability-of-ai-inventions. [Last accessed on 24 Aug 2025].

Kapustana O, Burmakina P, Gubina N, Serov N, Vinogradov V. User-friendly and industry-integrated AI for medicinal chemists and pharmaceuticals. ArtifIntell Chem. 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.aichem.2024.100072.

Han R, Yoon H, Kim G, Lee H, Lee Y. Revolutionizing medicinal chemistry: the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in early drug discovery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Sep 6;16(9):1259. doi: 10.3390/ph16091259, PMID 37765069.