Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 11, 1-9Review Article

NATIONAL CYBERSECURITY FRAMEWORKS: AN OVERVIEW OF U.S.A., AUSTRALIAN AND JAPANESE REGULATORY APPROACHES

SRAVYA ARIKATLA, MANISHA PENCHALA, PRASANTHI D.*

Department of Regulatory Affairs, G. Pulla Reddy College of Pharmacy, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-500028, India

*Corresponding author: Prasanthi D.; *Email: prasanthidhanu@gmail.com

Received: 30 Jul 2025, Revised and Accepted: 25 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Cybersecurity has become a top priority for nations worldwide as digital threats grow in complexity and frequency. Countries like the United States, Australia, and Japan have developed strong regulatory and strategic frameworks to address these evolving challenges. In the United States, cybersecurity efforts are supported by legislation such as the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) and the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA), which focus on risk management, public-private coordination, and national defence. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) plays a key role in overseeing national preparedness and response activities.

Australia has taken significant steps to strengthen its cybersecurity infrastructure through the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) and legal mandates under the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act. The country also enforces strict data protection rules via the Privacy Act 1988, including mandatory breach reporting and increased penalties for non-compliance.

Japan’s approach is guided by the Basic Act on Cybersecurity, which lays the foundation for government and industry cooperation. The National Centre of Incident Readiness and Strategy for Cybersecurity (NISC) lead policy coordination and national defence efforts. Japan also prioritizes personal data protection through the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), aligning with global privacy standards.

Together, these regulatory efforts reflect a growing international recognition of cybersecurity as essential to national security, economic stability, and public trust. While tailored to national contexts, these frameworks emphasize preparedness, resilience, and collaboration in securing the digital landscape.

Keywords: Software bill of materials (SBOM), Cybersecurity, Cyberattack, OTS software, Cybersecurity, Vulnerability, Software as medical device

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i11.56328 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

To identify relevant literature, we conducted a structured search across multiple sources, including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, as well as official regulatory authority websites such as the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA, Australia), and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA, Japan). But there are limited articles published on cybersecurity regulations. The search was limited to publications and regulatory documents available in English and published between 2010 and 2024, with emphasis on official regulatory updates, guidance documents and review articles.

Healthcare improvement may be a progressive segment where computerized innovations drive victory, with exponential development seen in a computing framework, including progressions in therapeutic gadgets. The utilization of computerized wellbeing apparatuses has the potential to altogether move forward person-centered care by upgrading the precision conclusion and treatment of illnesses. For the clinical appropriation of any advanced healthcare innovation, proof is required to begin with, and their impacts must be surveyed some time recently joining them into healthcare frameworks such as Electronic Wellbeing Records (EHRs) [1].

May 2015, the then Minister of Health declared the development of a digital health authority to mark the beginning of a new era for digital healthcare across Australia. Master requires physicians, nurses, and patients with unique end-user devices (e. g. smartphone, laptop, or tablet) authorization to access a program. This is responsible for prescription processing, database management, data collection, creation of subsystems, and management of knowledge base [2].

So, due to this and advancements in recent years, the healthcare sector has faced a surge in cybersecurity threats, both in frequency and severity, with a heightened potential for clinical harm. Such disruptions can result in serious clinical consequences, including delays in diagnosis or treatment, thereby putting patient health and safety at risk.

The most significant are the FDA recommendations for managing cybersecurity risks in order to secure the patient and the information housed, created, and processed by the medical device. Guidance such as "Content of pre-market submissions for management of cybersecurity in medical devices" is intended to address protection throughout the design and development stages by identifying potential security risks [3].

Vulnerability is defined as a flaw that can be exploited, whether in hardware, software, firmware, operating systems, medical devices, networks, people, or processes. All of these components create an information system and are essential to its operation. A threat is the potential for a vulnerability to be exploited, and the risk is estimated by taking into account the chance of a threat occurring as well as the severity of the potential consequence [4].

An excellent example is the recent Log4j vulnerability, which affects the widely used Apache Log4j logging framework, which is used worldwide by several healthcare systems to handle logs and diagnose problems. The cybersecurity weakness allowed attackers to execute arbitrary code on affected systems, resulting in data breaches and countless security issues. Such incidents have pushed governments around the world to impose stringent laws to maintain safe healthcare systems and private facilities [5]. While, the FDA has implemented the security strategy prioritization for SaMD which is given in fig. 1.

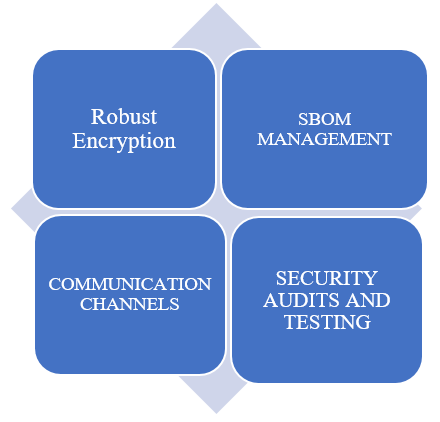

To secure Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), focus on these priorities:

Strong encryption: Use HTTPS (Hyper Text Transfer Protocol Secure) with TLS (Transport Layer Security, version 1.3) 1.3version and MTLS (Mutual TLS) to protect data in transit and at rest.

SBOM management: Maintain an accurate SBOM, monitor vulnerabilities, and patch promptly.

Secure communication: Ensure protected channels between devices and cloud services using MTLS and best practices.

Regular testing: Perform security audits and penetration tests to detect and fix vulnerabilities early [6].

Fig. 1: Security strategy to prioritize SaMD [6]

Cybersecurity is “the process of preventing unauthorized access, modification, misuse or denial of use, or the unauthorized use of information that is stored, accessed, or transferred from a medical device to an external recipient”

Cybersecurity measures aim to ensure that medical devices remain secure and functional, reducing the risk of failures caused by malicious activities or system breaches.

Data and systems security refers to the condition in which a medical device’s information assets—both data and system functions—are adequately protected against threats to their confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

Information security is “protection of information and information systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction in order to provide confidentiality, integrity, and availability”.

Security encompasses the protection of data and information to prevent unauthorized access or modification, while ensuring that authorized users maintain necessary access without interruption.

Cybersecurity regulations and standards for medical device software

Regulatory framework

In US, the FDA is the regulatory authority that provides the regulations of cybersecurity under then Centre for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) or the Centre for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) [6].

The regulations include OTS software, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) framework, SoC2 framework, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)1996, ISO/IEC 29147:2014 and ISO/IEC 30111:2013, AAMI TIR57. Each regulation has been discussed individually in detail.

Cybersecurity for networked medical devices containing OTS software, 2005

OTS software is increasingly being investigated for inclusion into medical devices as the use of general-purpose computer hardware becomes more ubiquitous. The deployment of OTS software in a medical device enables the manufacturer to focus on the application software required to perform device-specific functions. The medical device maker utilizing OTS Software normally relinquishes software life cycle control, but remains responsible for the medical device's continuous safe and effective operation [7].

Examples of medical equipment using OTS software (2014)

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) eye movement evaluation device

This prescription-only device is designed to assist in the evaluation of mild TBI, commonly referred to as a concussion. Utilizing a commercial OTS mobile phone and its built-in camera, the device tracks a patient's eye movements. The captured data is then analysed to determine the presence of eye movement patterns associated with mild TBI. Based on the analysis, the device provides a positive or negative indication, aiding healthcare professionals in diagnosing potential TBI-related impairments.

Retinal diagnostic software device

This prescription-based device incorporates an Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ml)-enabled algorithm that analyses retinal images for diagnostic screening purposes. The software is designed to detect retinal diseases or abnormalities by evaluating photographic data, supporting clinicians in the early identification and management of retinal conditions [8].

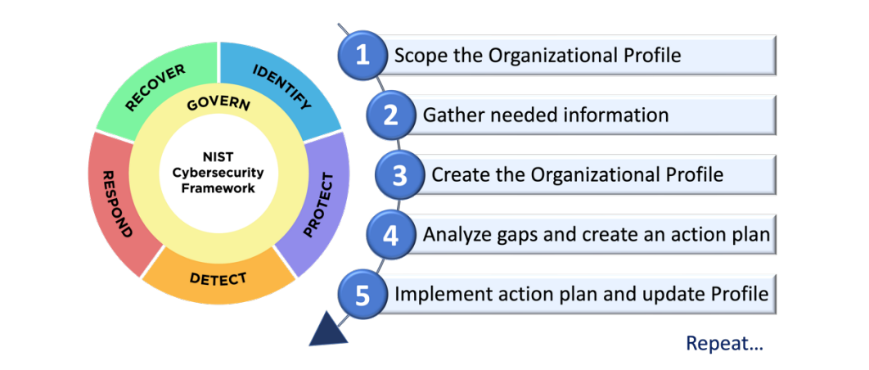

The FDA guidance documents (2014, 2016) advocate using and adopting the voluntary NIST cybersecurity framework's five basic functions: identify (ID), protect (PR), detect (DE), respond (RS), and recover (RC). In January 2017, NIST released a proposed cybersecurity framework core functions and outcomes given in table 1 and framework in fig. 2.

Table 1: NIST cybersecurity framework core functions and outcome categories

| Function identifier | Outcome categories | Reference |

| ID | Recognize and understand cybersecurity risks to systems, assets, data, and capabilities. | [7] |

| PR | Develop and implement safeguards to limit or contain the impact of potential cybersecurity events. | |

| DE | Implement activities to identify the occurrence of a cybersecurity event | |

| RS | Take action regarding a detected cybersecurity incident to mitigate its impact. | |

| RC | Develop plans for restoring capabilities or services that were impaired due to a cybersecurity event. |

Fig. 2: NIST Framework in US [9]

The NIST cybersecurity framework is a set of guidelines developed by the U. S. NIST to help organizations manage and reduce cybersecurity risks. It’s built around five core functions: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover, which were discussed in the above table, providing a structured approach to securing systems and data while improving resilience against cyber threats [7].

NIST unveiled the Cyber Security Framework 2.0 (CSF 2.0) in 2024, the most significant update since CSF 1.1 was issued in 2018. CSF 2.0 extends its reach beyond critical infrastructure cybersecurity, addressing a broader variety of institutions, including small schools, nonprofits, governmental agencies, and businesses, regardless of cybersecurity experience.

The cybersecurity framework now encompasses six core functions: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover and Govern providing a holistic approach to managing cybersecurity risk.

SOC2 framework

The SOC2 Framework, designed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), is a trust-based cybersecurity framework and auditing standard for suppliers. Partners manage client data securely. SOC2 provides over 60 compliance requirements and audit methods for third-party systems and controls. An audit could take a year to complete. A report is generated to certify a vendor's cybersecurity posture. Adopting SOC2 security frameworks can be challenging, especially for firms in the financial or banking sectors with higher compliance requirements. However, this security architecture is crucial for any third-party risk management program [9].

HIPPA

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is a U. S. federal law enacted in 1996 (Public Law 104-191) to establish national standards for the protection of Protected Health Information (PHI). HIPAA sets forth privacy and security requirements for healthcare providers, insurers, and other entities that handle PHI. HIPAA requires that e-mails containing health-related information be encrypted in transit, unless the patient has given written authority for the organization to send the information unencrypted (Wittkop, 2016, p. 38). Non-compliance with HIPAA can result in civil and criminal sanctions. To ensure the protection of electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI), HIPAA's Security Rule provides three types of safeguards:

Administrative safeguards include security management policies and processes, security personnel assignments, information access control, workforce training and supervision, and periodic security measure evaluations.

Physical safeguards include restricting access to premises, safeguarding workstations and devices, and putting in place steps to prevent illegal physical access to ePHI.

Technical safeguards are technology-based precautions that secure access to and transmission of ePHI, such as encryption, access control, and audit controls.

The FDA regards the international standards ISO/IEC 29147:2014 and ISO/IEC 30111:2013 as useful resources for controlling cybersecurity in medical devices.

ISO/IEC 29147:2014 establishes guidelines for the responsible disclosure of potential vulnerabilities in products and online services. It covers the best procedures for reporting, coordinating, and resolving security issues, assisting manufacturers in developing effective vulnerability disclosure programs.

ISO/IEC 30111:2013 describes how to identify, evaluate (triage), and remediate vulnerabilities in products and services. It helps suppliers establish organized techniques for detecting and addressing cybersecurity issues throughout a product's lifespan.

By citing these guidelines, the FDA urges medical device manufacturers to use strong vulnerability management techniques that are consistent with worldwide best practices for cybersecurity risk mitigation.

AAMI TIR57 (Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation Technical Information Report), ISO 14971, and NIST SP 800-30 (National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication) Rev. 1: AAMI TIR57:2016 advises medical device producers on handling information security risks connected with medical devices. Its primary goal is to assist manufacturers in addressing security threats that may jeopardize the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of a device or the data it processes. According to the report, the purpose is to "manage risks from security threats that could impact the confidentiality, integrity, and/or availability of the device or the information processed by the device" (AAMI TIR57, 2016, p. vii). This technical information report is based on the principles of ISO 14971:2007, an internationally known standard for medical device risk management. AAMI TIR57 recommends developing a separate risk analysis process that focuses on security-related impacts identified through a dedicated security risk assessment. The security risk management approach advocated by AAMI TIR57 (2016) includes developing a security risk management plan, analysing security risks, evaluating security risks, controlling security risks, assessing overall risk acceptability, creating a security risk management report, and gathering production and post-production data [7].

The TGA, Australia's national regulatory agency for therapeutic products, has issued extensive guidelines for medical device manufacturers to mitigate cybersecurity threats. These objectives are articulated in regulatory materials including the Australian Regulatory Guidelines for Medical Devices (ARGMD) and cybersecurity-specific guideline documents [10].

The Australian Government announced the Australian Cyber Security Strategy (ACSS) in 2016, acknowledging that improving cybersecurity is a top concern for the whole economy. The strategy highlights important actions to improve Australia's overall cybersecurity posture while also promoting the growth of the local cybersecurity industry.

The department of defence and allied agencies, most notably the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), are largely responsible for implementing this policy through the ACSC. These organisations work together to provide a cyber-secure environment that ensures stability and security for both businesses and individuals across Australia.

Mitigating cybersecurity threats is crucial for adhering to the Essential Principles (EP), as they can pose safety concerns. To comply with this, a producer may need to address certain cybersecurity elements. Essential Principles will differ depending on the type of gadget that may include: Off-label usage of gadgets by clinicians in specific situations, unauthorized device access or modification, exploitation of software or hardware vulnerabilities, unsupported user customization to meet specific needs or preferences and use in insecure operating environments.

Additional regulatory obligations for medical device cybersecurity, in addition to the applicable EP are detailed below in table 2.

The Japan Federation of Medical Devices Associations (JFMDA) is collaborating with the Pharmaceutical Safety and Environmental Health Bureau (PSEHB) of MHLW, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JAMRD) cybersecurity research group to develop national guidance titled "Security in Healthcare Intelligence, Electronics, Legacy Systems, and Digital Transformation for Medical Devices (SHIELD for Med)". SHIELD for Med is a program for Marketing Authorisation Holders (MAHs) in Japan that supports the implementation of International Medical Devices Review Forum (IMDRF) guidance and strengthens the country’s medical device cybersecurity framework. It aims to enhance the resilience of Japan’s medical systems through future collaboration with regulatory agencies and other government bodies connected to healthcare and cybersecurity. The initiative is led by the JFMDA [12].

The rising usage of wireless, Internet, and network-connected devices has highlighted the importance of effective cybersecurity in ensuring medical device safety. Cybersecurity events have left medical devices and hospital networks unworkable, causing disruptions in patient care across healthcare facilities. Such incidents may cause patient injury as a result of delays and/or errors in diagnosis and/or therapeutic treatments, among other things. To reduce cybersecurity risks for patient safety, manufacturers, healthcare providers, and regulators must share responsibilities and implement total product lifecycle cycle management.

Since 2015, various notifications for healthcare practitioners and manufacturers have been published [13].

Table 2: Additional regulatory obligations for medical device cyber security

| Specification | Coverage | Reference |

UL 2900-1 Software Cybersecurity for Network Connectable Products, Part 1: General Requirements UL 2900-2-1 Software Cybersecurity for Network Connectable Products, Part 2 1: Particular Requirements for Network Connectable Components of Healthcare and Wellness Systems |

Applies to network-connected goods that must be reviewed and tested for vulnerabilities, software flaws, and malware: (i) developer risk management process requirements; (ii) vulnerability testing techniques; and (iii) security risk control criteria. There are specific requirements for Information Technology (IT) networked components of healthcare and wellness systems. This standard evaluates the security of medical equipment, accessories, and data systems. |

[11] |

| IEC 80001 (series) addresses risk management in IT networks with medical devices. | The 80001 series of standards outlines the roles, responsibilities, and activities involved in managing risks associated with IT networks that incorporate medical devices, with a focus on safety, efficiency, data security, and system security. | |

ISO/IEC 29147 Information technology -Security techniques -Vulnerability disclosure |

This standard provides guidelines for the responsible disclosure of cybersecurity vulnerabilities in products and services. | |

| ISO/IEC 30111 | Explains how to tackle potential vulnerabilities in a product or system and Online service. |

Cybersecurity guidelines

On July 24, 2018, MHLW issued a notification titled "Guidance on Ensuring Cyber Security of Medical Devices". This advice serves as a supplement to the notification "Ensuring Cyber Security of Medical Devices". The goal of this guidance is to offer MAHs with practical instructions for addressing cybersecurity activities during the pre-market design and development phases as well as the post-market phase. With this guideline, MAHs can validate compliance with medical device safety and effectiveness criteria, thereby lowering patient risk. This guidance's objectives are:

• Identifying medical devices and their use environments which includes identifying medical devices that are subject to this guidance, and identifying medical device use environments.

Consider cybersecurity hazards while connecting medical devices, including wired and wireless networks and USB ports.

• Addressing cybersecurity by establishing baselines for risk management of medical devices, taking into account indications, users, and settings of usage. Providing MAHs assistance through maintenance contracts and collaboration with healthcare providers as needed.

• Ensuring Post-Market Safety where MAHs should include cybersecurity information in safety information and collaborate with distributors, service/maintenance providers, and healthcare providers to assure post-marketing safety. MAHs should instruct used medical device distributors to follow "Enforcement regulations of Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy, and Safety of Products Including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Article 170)" for proper cybersecurity measures.

The IMDRF guidance, "Principles and Practices for Medical Device Cybersecurity," was published in April 2020 to give broad principles and best practices for medical device cybersecurity and allow worldwide alignments among regulatory bodies.

On May 13, 2020, MHLW published a notification, "Publication of Guidance on the Principles and Practices for Medical Device Cybersecurity by the IMDRF," which was fully translated into Japanese [12].

Premarket requirements under cybersecurity regulations across three countries

When preparing FDA medical device premarket filings, businesses must demonstrate good cybersecurity management. The FDA (2014) suggests that as part of the software validation and risk analysis, a cybersecurity vulnerability and management strategy be established. Such a strategy includes the following activities:

First, manufacturers must identify all important assets, threats, and vulnerabilities associated with the medical device, including those linked to its software, hardware, and networking capabilities. Second, they should evaluate the possible impact of the detected threats and vulnerabilities on device functionality and end-user or patient safety. Third, determine the likelihood that these vulnerabilities will be exploited by bad actors. Fourth, based on the effect and likelihood evaluations, manufacturers must identify the amount of risk and execute suitable risk-reduction initiatives. Finally, residual risks, those that remain after mitigation measures have been implemented should be assessed to ensure they meet set tolerance standards.

Performing security risk management differs from performing safety risk management, as stated in ISO 14971. The difference in the performance of these processes stems from the fact that the scope of potential harm and risk assessment parameters may change across the security and safety contexts. Furthermore, while safety risk management focuses on physical injury, property or environmental damage, or delays and/or denial of service due to device or system failure, security risk management may contain hazards that might cause indirect or direct patient harm. There may also be hazards that are not covered by the FDA's assessment of safety and effectiveness, such as business or reputational issues [7].

On September 27, 2023, the FDA issued a final guidance titled Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions. This final guidance updates a draft guidance of the same title issued on April 8, 2022, and the agency’s 2014 final guidance titled “Content of premarket submissions for management of cybersecurity in medical devices”.

The newly released final guidance is largely similar to the April 2022 draft but offers more detailed recommendations regarding conducting cybersecurity risk assessments, considering interoperability, and the types of documents to include in premarket submissions to the FDA.

The structure and content of the new guidance are similar to the previous version, though it includes two new substantial subsections within the security risk management section.

It also introduces a new appendix that outlines specific documentation elements recommended for inclusion in premarket submissions, which now also apply to Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) submissions. Additionally, the guidance includes a number of new definitions for cybersecurity terms that were not present in the prior version.

One significant addition in the final guidance is a new Appendix 4, which features a checklist of documents the FDA suggests be submitted with premarket submissions.

This checklist also points out which documents may be beneficial to include with an IDE but are not specifically recommended for such submissions. On the other hand, architecture views and labelling are specifically recommended for submission in an IDE.

Moreover, the final guidance introduces and defines several new key cybersecurity terms in a new Appendix 5.

While many of these terms are new to the guidance, they are drawn from existing definitions found in widely recognized sources such as NIST, the Joint Security Plan, ISO/IEC standards [14].

The advice document, Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Premarket Submission Content, was released on June 27, 2025. The major change from 2023 to 2025 guidance is the addition of a new Section VII.

This section explains how to apply the requirements of Section 524B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDandC Act) concerning the cybersecurity of connected medical devices.

The documentation required by Section VII includes a Vulnerability Monitoring and Management Plan 524B(b)(1), a Cybersecurity Design and Maintenance Process 524B(b)(2), and a SBOM 524B(b)(3). Even in cases where modifications are made to an existing device that have no impact on its cybersecurity and where such documentation did not previously exist, the FDA still expects certain documentation to be submitted. Specifically, the manufacturer must provide a vulnerability monitoring and management plan, demonstrate that there are no critical vulnerabilities, and also submit the SBOM [15].

Pre Market requirements in Australia include that manufacturers must consider cybersecurity during the design and development process. This includes: Technological components include cybersecurity penetration testing, modular design architecture, secure operating systems, software evolution, and controlled access and content delivery.

Environmental factors such as network connectivity and data upload/download are relevant to the device's intended use.

Physical factors include mechanical locks on devices and interfaces, secure network infrastructure, and correct disposal of sensitive paper-based data.

Social factors include mitigating social engineering risks such as phishing, impersonation, luring, and tailgating. Manufacturers should keep a SBOM to aid in risk assessment when a vulnerability is discovered. Manufacturers are required to notify the TGA (as per post-market standards) and the wider industry about newly found cybersecurity vulnerabilities and associated dangers [11].

Cybersecurity risk monitoring

To reduce cybersecurity risks throughout the design and development phases, two main approaches can aid in early risk identification. These strategies, combined with adherence to the EP, promote proactive risk management. They include,

Secure by design

Detecting cybersecurity flaws and hazards in the early stages of device design and development. Early assessment enables the implementation of effective security measures, such as reducing the attack surface and guaranteeing secure coding techniques. Resources such as the Software Assurance Forum for Excellence in Code (SAFE Code) provide information on secure software development.

Quality by design involves identifying and minimizing potential risks connected with medical device functions, manufacturing processes, and the environment. This builds on the secure by design method. These dangers may include cyber security, privacy, usability, safety, and other associated concerns. Adding functions, such as Bluetooth connectivity, may improve usability, but their development, manufacturing, and use may pose cybersecurity threats.

Increased exposure raises the risk of a cybersecurity vulnerability being exploited, offering unacceptable threats. Early assessment helps achieve a better balance between functionality and cybersecurity.

To address cybersecurity threats, the NIST recommends that organizations develop a risk management strategy in accordance with its Cybersecurity Framework (similar to USA) to meet Australia's regulatory compliance requirements.

Risk management strategies

Risk management strategies involve the ongoing process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks. This is essential for medical devices to meet the EP. Cybersecurity risk management can be integrated into these strategies. It's also acceptable to conduct a separate cybersecurity risk assessment alongside the product risk assessment.

Two approaches for managing risk include the process outlined in ISO 14971 and the cybersecurity framework developed by the U. S. NIST.

While ISO 14971 is the most commonly used approach, other methods can also be applied as long as they ensure that manufacturers thoroughly assess, control, and monitor risks [16]. On July 20, 2023, Japan released a notification addressing Questions and Answers for Pre-Market Applications that was issued, incorporating cybersecurity requirements into the application procedure. This covers documents on cybersecurity requirements, the SBOM, and considerations for commercially available medical equipment. Marketing Authorization Holders (MAHs) must document their cybersecurity requirements, referring to the documentation control number within the Summary Technical Documentation (STED).

In Japan, MAHs must assess the cybersecurity risks associated with their medical devices, with risk management tailored to each device's unique characteristics. To assist with this, Japan's regulatory authorities developed the Guidance on Ensuring the Cybersecurity of Medical Devices, which defines regulatory expectations and necessary countermeasures.

To accurately assess cybersecurity risks, MAHs must determine the intended use environment (e. g., medical facility or home setting). Examine how the gadget connects to networks, whether wired or wireless. Consider cases where data is exchanged with external equipment, such as USB memory devices, and build distinct risk management techniques accordingly [17].

Data to be included in pre-market submission include:

General requirement

Implement cybersecurity-related actions in accordance with the quality management system. Create an activity to alert the regulatory authorities and the user about the vulnerabilities. Clarify the security policy and contact information for security, as well as the mechanism for disclosing vulnerabilities to clients using a quality management system. Risk management should take into account security vulnerabilities and threats, among other factors.

Software development process

Consider security upgrades and development environment security when planning your project. Specify the security requirements and capabilities. Security should be considered during design and implementation.

Security risk management process

Estimate and assess relevant dangers, identifying relevant vulnerabilities while taking into account planned usage and the environment of use, and control the threats using risk control measures and monitoring their efficacy.

Software configuration management process

Implement configuration management with change controls and change history for the development, maintenance, and support processes. Create the SBOM as a result of the configuration management procedure.

Software problem-solving process

Establish a procedure for conveying and handling information about security vulnerabilities, and follow the protocols when dealing with security issues, such as information disclosure [18].

Post-Market surveillance requirements in us, Australia, Japan

The FDA’s 2016 guidance on post-market cybersecurity emphasizes the importance of implementing a proactive and comprehensive risk management program for medical devices. This program should be integrated into the overall risk management process and is intended to ensure the continued safety and effectiveness of devices throughout their lifecycle.

Key elements of such a program include:

Monitoring cybersecurity intelligence sources, such as the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database (https://cve. mitre. org), to stay informed about emerging threats and vulnerabilities.

Maintaining robust software lifecycle processes, which ensure that security considerations are addressed during the design, development, maintenance, and decommissioning phases.

Assessing vulnerabilities and their potential impact, enabling manufacturers to evaluate the risk associated with identified cybersecurity issues and take appropriate corrective actions.

Monitoring cybersecurity resources to detect and recognize possible security vulnerabilities and threats. Ensuring strong software development processes that involve checking for new issues in third-party software components throughout the entire life of the product, as well as testing and confirming software updates and fixes that fix these weaknesses, including those in pre-made software.

Recognizing, evaluating, and understanding how a security flaw affects the system [19].

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is urging medical device makers to be more careful and include protective measures at every stage of product development to lower health and safety dangers.These guidelines are for both existing and new medical devices that are part of a connected system, include software or firmware, or are software-based applications themselves [20].

Reporting cybersecurity issues to the FDA

The FDA examines cybersecurity issues with medical equipment as part of its market monitoring. Facilities for manufacturers, importers, and device users. See Medical Device Reporting (MDR) for more information on obligatory reporting obligations.

Healthcare providers can report cybersecurity issues with medical devices using the MedWatch voluntary report form (Form 3500). Patients and caregivers can report cybersecurity issues with medical devices using the Med Watch voluntary report form (Form 3500B) [21].

In Australia, for successful maintenance of surveillance program, manufacturers and sponsors must continually assess and manage the cybersecurity risks connected with medical products. As the cybersecurity threat landscape changes rapidly, a compliant risk management strategy should show how these risks are reviewed and updated on a regular basis. Even cybersecurity incidents that do not directly affect a medical device are part of the larger threat landscape and must be addressed in a compliant medical device cybersecurity risk management plan [11].

Medical devices must continue to meet the essential requirements outlined in the Essential Principles once they are listed on the ARTG. This applies throughout the entire lifecycle of the device, ensuring continued compliance with legislative requirements and the TPLC strategy. As part of this process, risk management and quality management systems need to be regularly reviewed and updated to support ongoing inclusion on the ARTG.

Cybersecurity risk needs to be assessed and managed as part of the post-market risk management process.

This includes frameworks such as ISO 14971 and the NIST cybersecurity framework. Cybersecurity risk is a recurring activity, not limited to the pre-market stage, as the nature of these risks evolves over time. Therefore, it requires continuous monitoring and management throughout the product life cycle.

For manufacturers and sponsors, cybersecurity risk management should be integrated with post-market monitoring activities.

It is essential that they develop an understanding of how cybersecurity vulnerabilities might lead to exploits and threats, and how these could affect the safety of the device. This includes identifying the appropriate actions to take in response to changes in a device's cybersecurity risk profile, such as initiating a recall, releasing a safety alert, providing a routine update, or reporting an unintended effect to the TGA [16].

Uniform recall procedure for therapeutic goods (URPTG)

When dealing with cybersecurity issues in medical devices, sponsors must refer to the Uniform Recall Procedure for Therapeutic Goods (URPTG) and take the necessary steps.

Immediate recalls

Cybersecurity vulnerabilities, threats, or dangers that cause immediate and serious harm to user or public health and safety may need an urgent recall. These concerns could also suggest actual or prospective product manipulation. In such cases: Sponsors must speak with the URPTG and follow the proper processes. The Australian Recall Coordinator should be called promptly.

Non-immediate recalls

Non-immediate recalls may be required when cybersecurity vulnerabilities or threats result in actual or potential deficiencies in the safety, quality, performance, or presentation of a medical device, as such actions are necessary to protect user health and safety. If such issues are identified, sponsors are expected to review the URPTG and follow its guidance as appropriate. Before concluding that no recall is necessary, sponsors must carefully assess whether the issue warrants a recall. They are also responsible for determining the type, class, and level of recall, taking into account the risk to patients, the nature of the deficiency, and the applicable recall classification. Since each situation is unique, every case must be evaluated individually to determine the most appropriate course of action.

Examples of cybersecurity recall actions

The Uniform Recall Procedure for Therapeutic Goods (URPTG) identifies four categories of recall activities. Here are two examples of cybersecurity risks: Recall is the permanent removal of a medicinal product from the market or use. This may be required for high-risk cybersecurity vulnerabilities in medical devices that cannot be repaired in the field or when a solution is not expected within a reasonable timescale (to be established after consultation with the TGA). Product Defect Correction involves repairing, modifying, adjusting, or re-labelling a device to solve quality, safety, performance, or presentation faults. To address cybersecurity, this may include software upgrades, revisions to accessories, or changes to operating instructions.

This approach may be appropriate for medical equipment vulnerabilities that can be addressed.

• A danger warning is issued if an implanted therapeutic good cannot be recalled within a reasonable timeframe.

• A product defect warning alert is provided to increase awareness about situations where ceasing treatment may be riskier than continuing to use the defective product (e. g., when no substitute product is available or a recall would cause treatment to halt). This option may be appropriate for vulnerabilities that cannot be repaired, but the risk of allowing the defective product to continue in use is acceptable with proper management.

Classification of cybersecurity recall actions

Recall actions involving cybersecurity vulnerabilities in medical equipment are designated as Class I, II, or III, depending on the seriousness of the risk to patient health and safety.

Class I-Most major risk refers to situations where using or being exposed to a defective medical device can lead to major health repercussions or even death.

Examples include software flaws that cause linear accelerators to produce inaccurate radiation doses or target the wrong spot. Hardware or software faults in ventilators cause the unit to shut down while in use.

Class II-Moderate risk refers to situations where a defective device may produce transient or reversible ill health consequences, with a low risk of disastrous outcomes.

For example, software or mechanical problems in infusion pumps can cause visible or auditory alerts, resulting in delayed therapy.

Class III is the lowest risk category, indicating that using a defective medical device is unlikely to harm one's health.

Examples of non-recall actions in cybersecurity

Not every cybersecurity issue necessitates a recall. Non-recall activities may be justified if a medical device continues to meet al l specifications and regulatory standards, with no concerns about safety, quality, performance, or appearance. These decisions must be made in consultation with the TGA. Here are some examples of non-recall actions:

Safety alerts are issued to advise users about a gadget that fulfils, requirements but may cause harm if not used properly. This may be useful if cybersecurity vulnerabilities are detected in widely used networks or accessories to which the device connects.

Product notification

Used to provide information about a medical device in situations where serious health risks are unlikely. This may be suitable if a vulnerability affects data systems or privacy but is unlikely to impact user health.

Quarantine

A temporary suspension in product supply while an issue or incident is being investigated. This non-recall action may be appropriate if a cybersecurity vulnerability is suspected of causing a problem but not yet confirmed.

Product withdrawal refers to the removal of a product from the market for reasons other than safety, quality, performance, or presentation. This move may be appropriate for withdrawing devices that are no longer maintained by the manufacturer or have become vulnerable as a result of the discontinuation of support for third-party components [11].

The new Procedure for Recalls, Product Alerts and Product Corrections (PRAC), which came into effect on 5 March 2025, replaces the Uniform Recall Procedure for Therapeutic Goods (URPTG) as the required process for sponsors undertaking market actions in Australia.

The PRAC is a complete rewrite of the URPTG to improve clarity and readability, while the overall market action process remains largely the same. Key changes include replacing the separate ‘recall’ and ‘non-recall’ categories with a single ‘market actions’ category, reducing the steps in the recall process from ten to five, and presenting information in clearer formats such as tables and visuals. It also clarifies when additional details are required for actions that may cause shortages or involve lengthy corrections, simplifies the definitions for Class and Level of market actions without changing their meaning, and removes legislative powers content, which will be published separately on the TGA website [22].

In Japan, the Early Post-marketing Phase Vigilance (EPPV) program was introduced in 2001. This unique system applies to newly approved medicines and involves safety monitoring activities carried out within the first six months after a drug is released onto the market. The MAH, who is responsible for the drug during this period, is required to collect information on adverse drug reactions (ADRs) from all healthcare facilities that use the medication and take necessary steps to ensure safety. The goal of EPPV is to promote the correct and appropriate use of medications in medical practice and to allow for quick responses to prevent serious adverse reactions. EPPV is considered a mandatory requirement for the approval of a product.

Future cybersecurity responses in Japan

To address medical device cybersecurity, MAHs must conduct risk assessments based on device characteristics and collaborate with stakeholders to implement appropriate mitigation measures. This includes healthcare providers. MAHs and business operators in Japan plan to implement IMDRF advice over three years to enhance medical device cybersecurity safety. We appreciate the understanding and assistance in creating systems with medical device MAHs to ensure cybersecurity [23].

Reporting of cyberattacks

According to the Act on Protection of Personnel Information (APPI) regulations, if a breach or threat of breach of personal data occurs and there is a risk of harm to individuals' rights and interests, business operators must report the incident to the PPC or other relevant supervisory bodies within three to five days of discovering the breach or potential threat. Furthermore, they are typically expected to give a detailed follow-up report within 30 days after the initial identification date. According to the TBA (Telecommunications Business Act), a telecommunications carrier must 'promptly' disclose any instance of infringement of communications secrecy to the competent authorities with jurisdiction over the location of its headquarters. The carrier must also report any further information within 30 days of learning about the incident [24].

Table 3: Comparative analysis of cybesecurity regulations for medical device

| Aspect | USA | Australia | Japan | References |

| Regulatory authority | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) | Pharmaceutical Medical Device Agency (PMDA) | |

| Key guidance/documents | 2023 Final Guidance on Premarket Cybersecurity (updated from 2014 and 2022 drafts) -Post-market Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices (2016) |

Medical device cybersecurity guidance for industry Nov 2022 | Guidance on Ensuring the Cybersecurity of Medical Devices; Q and A notification (2023), SHIELD for Med. | [3, 11, 13] |

| Premarket Requirements | Document cybersecurity risk management in premarket submissions (design controls, risk assessments, secure-by-design, vulnerability management planning). FDA recommends reporting planned patches/updates and including cybersecurity outputs in QMS documentation. | TGA expects manufacturers/sponsors to demonstrate how devices meet EP, include cybersecurity in TPLC, and maintain SBOMs for device-specific vulnerability assessment. | PMDA requires MAHs to document cybersecurity in premarket applications; explicit Q and A (20 Jul 2023) includes documentation requirements, SBOM, and handling of marketed devices. STED must reference documentation control numbers. | [3, 10, 18] |

| SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) | Encouraged/expected as part of risk assessment and vulnerability management planning in both pre-and post-market contexts (FDA guidance and more recent premarket recommendations). | TGA guidance explicitly recommends maintaining SBOMs to help assess device risk if vulnerabilities are detected. | PMDA Q and A (20 Jul 2023) introduced SBOM expectations for premarket applications — MAHs must provide SBOM information as part of documentation. | [3, 11, 18] |

| Post-market Requirements | FDA: proactive post-market vulnerability monitoring, triage, patching, risk-based decision making; report significant cybersecurity issues per existing adverse event/reporting pathways like Med Watch. | TGA: sponsors must monitor vulnerabilities, notify TGA as per URPTG procedures; inform industry where appropriate; non-recall and recall actions described in URPTG. | PMDA: MAHs must evaluate and manage cyberattack risks in post-market phase; report issues to regulators and implement countermeasures per guidance. JFMDA works with regulators on national guidance (SHIELD). | [19, 22, 23] |

| Standards and frameworks referenced | NIST Cybersecurity Framework (ID, PR, DE, RS, RC) recommended; ISO/IEC 29147 and 30111 referenced for vulnerability disclosure/handling; AAMI TIR57 and ISO 14971 approach for risk management also recommended. | TGA refers to international standards (ISO/IEC, AAMI), and ACSC’s Essential Eight is the national baseline for mitigation. | PMDA referencing IMDRF guidance, international standards; PMDA guidance aligns with ISO/IMDRF concepts and requires MAHs to follow risk-based approach and document cybersecurity measures (including SBOM) | [7, 11, 12] |

Limitations and future considerations

Nevertheless, even though it is generally effective, certain limitations continue to exist. The consistency of enforcement varies across different jurisdictions, especially regarding the oversight of manufacturers’ compliance after products enter the market and the prompt application of security updates. Variations in terminology, documentation formats, and SBOM requirements pose challenges for global manufacturers striving to meet regulations in multiple regions. Furthermore, the management of legacy devices remains inadequately addressed, with few technical solutions available for securing older products that are currently in clinical use.

Future efforts should aim at enhancing cross-border alignment of terminology, formats, and reporting timelines, reinforcing enforcement mechanisms, and creating specific technical guidance for the security of legacy devices. The wider implementation of real-time threat intelligence sharing platforms among regulators, manufacturers, and healthcare providers will further strengthen the overall resilience of medical device ecosystems globally.

CONCLUSION

This article presents an overview of emerging cybersecurity regulations for Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) in the United States, Australia, and Japan. It explores current frameworks and anticipates future developments aimed at mitigating cybersecurity vulnerabilities that could affect patient safety. The review highlights key regulatory components, such as the regulation of off-the-shelf software in the US and the shared emphasis on premarket and post-market cybersecurity requirements across all three countries. These typically involve risk management, risk assessment, and risk mitigation strategies. While there are common regulatory principles, each country follows a distinct approach shaped by its own healthcare and regulatory environment. The article offers meaningful insights that may inform regulatory strategies in other countries and support international efforts toward harmonized medical device cybersecurity standards.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Sravya A.: Planned and designed the concept of the manuscript, drafting the manuscript, literature search and review. Manisha P.: Supported in editing the manuscript and citation. Prasanthi D.: Designed the concept of the manuscript, supported in reviewing the manuscript, designing the final version to be Published.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Pachava VR, Krishna BS. Regulatory framework of cybersecurity for medical device software in USA, EU and India. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2023;15(5):49-54.

Prajwal A. 4.0-impact of the internet of things on health care. Int J Appl Pharm. 2020;12(5):64-9.

Food and Drug Administration. Content of premarket submissions for management of cybersecurity in medical devices (Draft guidance). United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2025. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm356190.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Williams PA, Woodward AJ. Cybersecurity vulnerabilities in medical devices: a complex environment and multifaceted problem. Med Devices (Auckl). 2015 July;8:305-16. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S50048, PMID 26229513.

Slabodkin G. FDA warns about Log4j cybersecurity vulnerabilities in medical devices. Med Tech Dive; 2021 Dec 20. Available from: https://www.medtechdive.com/news/fda-warns-log4j-cybersecurity-risks-medical-devices/611773.

Medcrypt. Software as a medical device: understanding regulations and security priorities. Medcrypt blog; 2024 July 2. Available from: https://www.medcrypt.com/blog/software-as-a-medical-device-understanding-regulations-and-security-priorities. [Last accessed on 15 Aug 2025].

Lechner NH. An overview of cybersecurity regulations and standards for medical device software. In: Proceedings of the central European conference on information and intelligent systems; 2017 Sep. Available from: https://archive.ceciis.foi.hr/public/conferences/2017/06/QSS-3.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Unitet States Food and Drug Administration. Off-the-shelf software use in medical devices: guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff. United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2019 Sep 27. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/71794/download. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Bit Sight. 7 cybersecurity frameworks to reduce cyber risk. BitSight Blog. Available from: https://www.bitsight.com/blog/7-cybersecurity-frameworks-to-reduce-cyber-risk. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Therapeutic Goods Administration. TGA cybersecurity and testing requirements for medical devices. Available from: htpps://www.medsectesting.com/tga-cybersecurity-and-testing-requirements-for-medical-devices.

Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medical device cyber security guidance for industry. Canberra (AU) Therapeutic Goods Administration; 2022 Nov. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/medical-device-cyber-security-guidance-industry.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

UL. Medical device cybersecurity in Japan. UL Solutions; 2021 Mar 19. Available from: https://www.ul.com/news/medical-device-cybersecurity-japan.

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Cybersecurity requirements for medical device product registration; 2023. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000266827.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Ropes, Gray LL. FDA finalizes guidance on medical device manufacturer cybersecurity responsibilities; 2023 Oct 10. Available from: https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2023/10/fda-finalizes-guidance-on-medical-device-manufacturer-cybersecurity-responsibilities.

Mitch. 2025 update of FDA premarket cybersecurity guidance. MD101 Consulting; 2025 Jul 4. Available from: https://www.cm-dm.com/post/2025-July4-update-of-FDA-Premarket-Cybersecurity-guidance.

Therapeutic Goods Administration. Complying with medical device cyber security requirements (guidance for manufacturers and sponsors). Canberra (AU) Goods Administration; 2019 July 1. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/guidance/complying-medical-device-cyber-security-requirements?utm. [Last accessed on 09 Aug 2025].

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). Recent trends in cybersecurity assurance of medical devices. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices safety information; 2020 Jun. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235348.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Cybersecurity requirements for medical device product registration; 2023. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000266827.pdf.

U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Postmarket management of cybersecurity in medical devices: guidance for industry and FDA staff; 2016 Dec. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/postmarket-management-cybersecurity-medical-devices.

ICON plc. FDA final guidance document on post-market cybersecurity. ICON insights blog; 2018 Apr 20. Available from: https://www.iconplc.com.insights/blog.2018/04/20/fda-guidance-onpostmarket-cybersecurity.

U. S. Food and Drug Administration. (n. d.). Cybersecurity in medical devices: reporting cybersecurity issues. FDA Digital Health Center of Excellence. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/cybersecurity#reporting. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Therapeutic Goods Administration. Procedure for recalls product alerts and product corrections (PRAC). Department of Health; 2025 Mar 5. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/how-we-regulate/monitoring-safety-and-shortages/procedure-recalls-product-alerts-and-product-corrections-prac.

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). Recent trends in cybersecurity assurance of medical devices. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices safety information; 2020 Jun. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235348.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). Recent trends in cybersecurity assurance of medical devices. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices safety information; 2020 Jun. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235348.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jul 2025].

Nagashima Ohno, Tsunematsu. In brief: cyberthreat detection and reporting in Japan. Lexology; 2025 Feb 5. from https://www.lexology.com.library.aspx?g=b5a4686a-ac39-4622-a928-a7b471b58a00.