Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 12, 36-41Original Article

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE PHYTOCHEMICAL, FREE RADICAL SCAVENGING AND ACID NEUTRALIZING POTENTIAL OF ETHANOL, ETHYL ACETATE, CHLOROFORM AND HYDROALCOHOLIC EXTRACT OF IPOMOEA RENIFORMIS CHOISY

ANIL PARASNATH SAO1*, KAVITA LOKSH2, GAURAV JAIN2, PHOOLSINGH YADUWANSHI3

1,2*IES Institute of Pharmacy, IES University, Bhopal-462044, Madhya Pradesh, India. 3Department of Pharmacy, IES Institute Technology Management, IES University, Bhopal-462044, Madhya Pradesh, India

*Corresponding author: Anil Parasnath Sao; *Email: anilsao181681@gmail.com

Received: 04 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 10 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to provide comparative evidenced of chloroform (CE), ethyl acetate (EA), ethanol (EE) and hydroalcoholic (HE) extract of leaves of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy belonging to Convolvulaceae for its free radical scavenging, acid neutralizing potential and phytochemical property.

Methods: The shade-dried leaves was extracted using Soxhlet apparatus and the extracts were subjected to determine phytochemical constituents, Antioxidant capacity by 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging method and acid neutralizing capacity for artificial gastric juice. A high resolution trinocular microscope equipped with camera was used to assess microscopical characteristics of transverse section of leaves.

Results: All four extract showed presence of glycosides, flavonoids, tannins, proteins and carbohydrates in abundance. Total phenolic content was highest 28.12±1.08 for EE extract measured in milligrams of gallic acid equivalent. Total flavonoids content was highest in EE 59.09±1.87 measured in milligrams of Rutin Equivalent per g of extract equivalent. The free radical scavenging potential can be acknowledged due to strong IC50 value of 52.24 µg/ml for EE extract using 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) dye and had the highest antioxidant activity, measuring 94.84±1.56% at 1000 µg/ml. The pH of extracts was 1.69, highest for EE extract. Similarly the consumed volumes of extract to neutralize artificial gastric juice to pH 3.0 was significantly better for EA and EE extract ranging 9.36±0.09 ml and 10.56±0.09 ml respectively, indicating high antacid potency.

Conclusion: Ipomoea reniformis Choisy leaf extract showed remarkable antioxidant capacity may be due to presence of phenols and flavonoids in higher concentrations and tends to possess positive gastric cytoprotection and ulcer healing potential.

Keywords: Soxhlet apparatus, Acid neutralizing capacity, Free radical scavenging, Extracts, Cytoprotective

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i12.56392 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Herbal medicine has a long history of serving in the treatment of several diseases [1]. Plant parts along with their extracts are used as medicinal agents to treat illness and maintain as well as promote health and are available as an inexpensive source of primary health care, especially in the absence of access to modern medical facilities [2]. The Ipomoea reniformis Choisy are traditionally employed as medicinal herbs in Africa, India, and other nations to treat a variety of illnesses and conditions in Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine [3]. It is found as a perennial creeper all over India, extraordinarily in moist areas across Gujarat, Bihar, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Goa, Karnataka and tropical areas of Africa [4]. According to published research on the plant's phytochemical analysis, the plant contains resin, glycosides, starch, reducing sugars, and ester derivatives of caffeic, p-coumaric, ferulic, and sinapic acids. Ipomoea reniformis has been employed in the indigenous medical tradition to treat a variety of conditions, including inflammation, epilepsy, laxatives, and diuretics. [5]. It is believed that an increased intake of herbal-tailored medicine or food rich in natural antioxidants lowers risks of gastric abrasion and concomitantly peptic ulcer [6]. Based on the fact that gastric ulcer induction involves oxidative stress and inflammation or microbial infection, the current study examines the acid neutralisation potential and antioxidant effect of this plant extract [7]. The literature study showed that Ipomoea reniformis Choisy has numerous activities, but an antiulcer activity study needs to be documented for the researcher society; therefore, we have selected this plant for the present study. Current antiulcer treatments focus on inhibition of acid secretion, acid neutralisation and/or targeting Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) which are accomplished by H2-receptor antagonists or anticholinergics or proton pump inhibitors [8]. However, they can cause adverse effects such as blurred vision, dry mouth, constipation, gynaecomastia and galactorrhoea, while proton pump inhibitors have been reported with serious renal problems [4].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of plant materials

The whole matured plant of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy was collected from the Gondia district of Maharashtra during Novembe, by hand picking method as this season pertains to suitable in phenology. Plant identification and authentication were performed by taxonomist of Department of Ayurvedic Medicine, Government Ayurvedic College Raipur, Chhattisgarh with certificate no. 14/2022. The copy of specimen is deposited for future reference. The green leaves were subjected to microscopic investigation. Later the leaves were subjected to shade drying and pulverised using a mixer grinder into coarse powder and stored in an airtight container for chemical evaluation and simultaneous extraction.

Microscopic investigation

The microscopic features can serve as one of the fundamental criteria and have always made it possible to identify plant material with speed and accuracy [9]. The transverse section (TS) of the leaf part was stained twice with safranin and washed with water. It was further dehydrated using strong alcohol and ultimately put in glycerine for examination and confirmation of lignifications at 40x resolution. High-resolution images of plants have been captured using a trinocular microscope equipped with a camera, which was used to take pictures at various magnifications.

Chemicals and reagents

All the chemicals used in this study, viz. 1-Diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH), ethyl acetate, chloroform, ethanol, ether, Molisch’s reagent, Fehling's solutions A and B, Benedict's reagent, Ninhydrin reagent, Mayer's reagents, Dragendroff's reagents, Wagner's reagents, Hager's reagents, sodium nitroprusside solution, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and gallic acid, were analytical grade and procured from SRN Scientific Suppliers, Kolkata, India.

Phytochemical screening

The coarse powder was extracted using selected solvents; here it was ethyl acetate (EA), chloroform (CE), and ethanol (EE) in Soxhlet extraction. Hydroalcoholic (HE) (50% v/v) extract was prepared by the maceration process. After distillation, the solvent was totally eliminated, and a vacuum desiccator was used to dry it. After that, the standard extracts were kept for further use at 4 °C in a refrigerator.

Test for carbohydrates

All our extracts were subjected to Molisch’s Test, Fehling’s Test, Benedicts Test and the Test for Starch following the standard procedure laid down in standard reference literature for estimation of carbohydrates [10].

Test for proteins and amino acids

To measure proteins and amino acids, the required amounts of various extracts were put through the xanthoproteic, Biuret, Millon's, ninhydrin, and heavy metal tests. [11].

Test for alkaloids

The four extracts were separately tested for the presence of alkaloids using alkaloidal reagents such as Mayer’s, Dragendroff’s, Wagner’s and Hager’s reagents and tannic acid [12].

Test for glycosides

A small amount of aqueous solution of all extracts was evaluated for the presence of glycoside content using Legal’s, Baljet’s, Borntrager’s, and Keller-Killiani’s tests [13].

Test for phytosterols

Phytosterol content was tested for all four extracts by refluxing with alcoholic potassium hydroxide until saponification and subjecting them to Liebermann’s, Liebermann–Burchard’s and Salkowski’s tests [13].

Test for flavonoids

All the available extracts were separately dissolved in ethanol and then subjected to the Ferric Chloride Test, Shinoda’s Test, Fluorescence Test, and Reaction with Alkali and Acid [14].

Test for phenolic compounds

The aqueous filtrate of all extracts was treated with various reagents like ferric chloride, copper sulphate, lead acetate, potassium dichromate and potassium ferricyanide solution to detect the presence of phenolic compounds [15].

Test for volatile oil

A small amount of powdered extracts was taken in a Cocking-Middleton apparatus and distilled for 6 h. The separation of volatile oil during this period indicates the presence of volatile oil [16].

Determination of total phenolic content

The Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and external calibration with gallic acid were used to measure the total phenolic contents in the crude extracts. A precise mixture of 0.2 ml of extract solution with 0.2 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was used [17]. Sodium carbonate was added after an interval of a few minutes, and the mixture was allowed to stand for a time period of 2 h at room temperature. The measurement of absorbance was taken at 760 nm using an ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer. An equation derived from the gallic acid calibration curve was used to determine the total phenolic content in milligrams of gallic acid equivalent. Three separate measurements of total phenolic compounds were made, and the average of the results was derived.

Determination of total flavonoids

The flavonoid content of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy extracts was determined using the spectrophotometric method. The ethanolic solution of the extracts along with 2% aluminium chloride, was incubated for an hour at room temperature. The absorbance was determined using a spectrophotometer λmax = 415 nm. For every analysis, the samples were produced in triplicate, and the absorbance mean value was determined. The calibration line was built, and the same process was carried out for the rutin standard solution. The amount of flavonoids in extracts was then quantified in terms of rutin equivalent (mg of RE/g of extract) after the concentration of flavonoids was determined (mg/ml) on the calibration line based on the observed absorbance [18].

In vitro antioxidant activity

Valuating in vitro antioxidant tests using the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical trapping method is relatively straightforward to perform and is cheap and easy on a practical basis. The molecule DPPH has a distinguished ability of delocalisation of its spare electron, which produces a deep violet hue and an absorption band in ethanol solution at around 517 nm. When a solution of DPPH is mixed with a substrate that can donate a hydrogen atom, it will give rise to the reduced form of DPPH with the loss of intensity of violet colour, which can be measured as absorbance using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The plant leaf extracts in different concentrations are diluted with methanol and DPPH solution. After 30 min, the absorbance is measured at 517 nm [19]. The percentage of the DPPH radical scavenging is calculated using the equation as given below:

….. (1)

….. (1)

In vitro acid neutralization capacity

All the extracts were propelled to evaluate the in vitro acid neutralising capacity in a concentration of 100 mg/ml against the artificial gastric acid. 3.2 mg of pepsin enzymes and 2 g of sodium chloride were dissolved in 500 ml of distilled water to create the artificial gastric acid for experimental purposes. The pH of this was brought down to 1.20 by adding a sufficient solution of 7.0 ml of 3M hydrochloric acid in 1000 ml of distilled water. Fordtran's model titration approach was used for determining neutralisation capacity. 90 ml of each extract solution was tested for its pH. The pH values of the sodium bicarbonate as a standard and water were also determined for comparison. Freshly prepared 90 ml of each test solution, water (90 ml) and the active control SB (90 ml) were added separately to the artificial gastric juice (100 ml). The pH values were determined to examine the neutralising effects on artificial gastric juice. The test samples were titrated separately with artificial gastric juice till the endpoint of pH 3. The consumed volume (V) of the artificial gastric juice was measured. The total consumed H+(mmol) was measured as 0.063096 (mmol/ml) × V (ml) [19, 20].

RESULTS

There are 24 nearby Ipomoea species in the state of Maharashtra, India, and more than 60 in India. An Ipomoea reniformis Choisy medicinal plant was selected for the study based on a review of the literature.

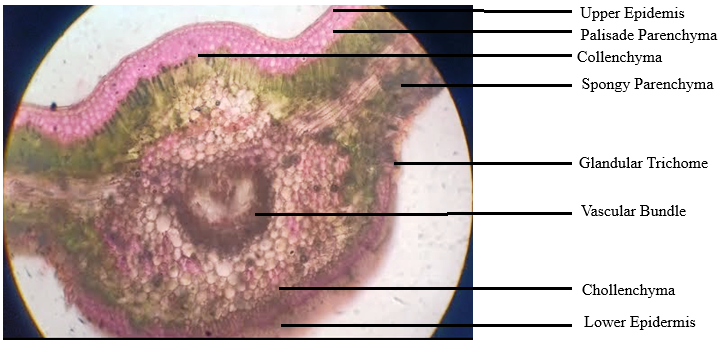

Microscopic investigation

As shown in fig. 1, the microscopic observations were found to align with the reports present by (Usnale SV et al. 2009) [21]. The transverse lamina of the leaf was dorsiventral. There was only one layer of cuticle covering the top epidermis, which had anomocytic stomata. The spongy parenchymas consist of 3 to 4 layers with thin cell walls. Calcium oxalate of the druses type was found in some cells. There are single-layered palisade cells. Like the upper epidermis, the lower epidermis was single-layered and had anomocytic stomata on top of a single layer of cuticle. The upper and lower epidermis is covered by a single layer of cuticle, and the midrib has a biconvex form. Three to four layers of thick-walled cellular parenchyma make up the collenchyma that lies under the upper and lower epidermis. Some starch grains have bowl-shaped vascular bundles made of lignified xylem and phloem. There are no trichomes.

Fig. 1: TS of the leaf of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy under 40x resolutions using a Trinocular microscope

Organoleptic properties and percentage extractive yield

A total of 35 g of dried and coarsely powdered leaves was employed for extraction using the Soxhlet method with chloroform, ethyl acetate, ethanol and ethanol: water (50:50) for about 10-12 h at 30 °C. The yield of chloroform extract (CE) was 3.32 g, ethyl acetate extract (EA) was 3.58 g, ethanolic extract (EE) was 3.48 g, and hydroalcoholic extract (HE) was 2.47 g, and the nature and colour of all extracts are represented in table 1.

Phytochemical evaluation

The extracts (CE), (EA), (EE) and (HE) showed the presence of phytochemicals such as alkaloids, glycosides, tannins, flavonoids, coumarins, cardiac glycosides, saponins, proteins and amino acids etc., represented in table 2.

Total phenolic content

Total phenolic content in crude extracts was measured using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, with gallic acid as an external calibrant; absorbance was read at 760 nm. From an equation derived from the gallic acid calibration curve, the total phenolic content was determined to be (CE) 6.21±0.13, (EA) 25.40±0.19, (EE) 28.12±1.08, and (HE) 16.84±0.19 in milligrams of gallic acid equivalent. Total phenolic compounds were measured in triplicate; the findings were averaged and summarised in table 3.

Table 1: Nature, color, and % extractive yield of Ipomoea reniformis extract

| Solvent used | Nature | Color | Yield of extract | |

| g | % | |||

| Chloroform (CE) | Smooth | Greenish | 3.32 | 09.48 |

| Ethyl Acetate (EA) | Smooth | Light | 3.58 | 10.22 |

| Ethanol (EE) | Sticky | Dark | 3.48 | 09.94 |

| Hydroalcoholic (HE) | Amorphous | Light | 2.47 | 07.05 |

Table 2: Qualitative analysis of phytochemical of Ipomoea reniformis choisy extract

| Phytochemicals analysis | Ethyl acetate | Ethanol | Chloroform | Hydro alcoholic |

| Alkaloids | ++ | ++ | + | -- |

| Glycosides | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Flavonoids | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Coumarin glycosides | +++ | +++ | -- | ++ |

| Anthraquinone Glycosides | ++ | ++ | -- | -- |

| Cardiac Glycosides | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Tannins | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Steroids | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Saponins | ++ | ++ | -- | ++ |

| Resins | ++ | ++ | -- | ++ |

| Terpenoids | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Carbohydrates | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Proteins | +++ | +++ | -- | +++ |

| Amino acids | ++ | ++ | -- | ++ |

The outcomes of the generic test for phytochemical constituents which produce colour was analyzed by visual subjective assessment which typically meant to represent: “+” (Presence); A low or weak presence of the phytochemical, “++” (Moderate Presence); A moderate or noticeable presence and “+++” (Strong Presence); A high or strong detection. While for instance, in flavonoids, the intensity of the phytochemicals was scored based on a semi-quantitative scale. The scores were assigned by measuring the absorbance of the final colored reaction product at 520 nm using a spectrophotometer, with criteria as follows:+, absorbance<0.3;++, absorbance 0.3-0.6; and+++, absorbance>0.6."

Table 3: Phenols content (as mg GA/g equivalent) of extracts of Ipomoea Reniformis

| S. No. | Extracts | mg GA/g of extract |

| 1 | Chloroform | 6.21±0.13 |

| 2 | Ethyl Acetate | 25.40±0.19 |

| 3 | Ethanolic | 28.12±1.08 |

| 4 | Hydroalcoholic | 16.84±0.19 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, n=3.

Table 4: Flavonoids content (as mg of RU/g of extract) of Ipomoea reniformis

| S. No. | Extracts | mg of RU/g of extract |

| 1 | Chloroform | 52.32±0.69 |

| 2 | Ethyl Acetate | 56.29±1.84 |

| 3 | Ethanolic | 59.09±1.87 |

| 4 | Hydroalcoholic | 24.54±1.87 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, (n=3).

Total flavonoids content

The spectrophotometric approach was used to quantify the amount of flavonoids present in extracts of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy as mg of RU/g. The total flavonoid content was found to be highest for (EE) 59.09±1.87, followed by (EA) 56.29±1.84, (CE) 52.32±0.69, and (HE) 24.54±1.87 in mg of RU/g of extract equivalent.

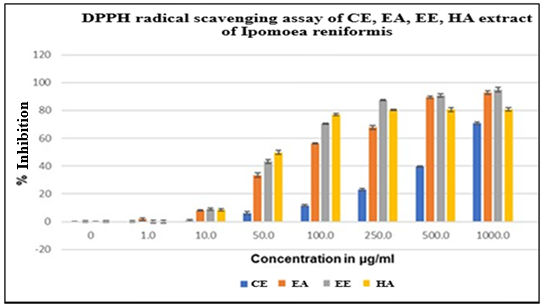

In vitro antioxidant activity

On extraction, the ethyl acetate and ethanolic extract of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy had shown satisfactory output, with sufficient concentration of flavonoids and phenolic content suggests its antioxidant potential, which was proven in various studies and was also represented by Raghuvanshi A et al. (2017) involving mechanisms such as scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and/or by chelating metal ions that can catalyze oxidation [22].

All the extracts of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy have significantly reduced the DPPH radicals in a concentration-dependent manner. The DPPH assay assessed the free radical scavenging property of all extracts by comparing the inhibitory concentration (IC50) and a standard using Vitamin C. As shown in fig. 2, the dominating antioxidant activity was shown by EE with an IC50 value of 52.24µg/ml and a standard of 85.08 µg/ml.

Fig. 2: The percentage inhibition concentration (50%) of various extracts after treating with DPPH reagent is shown in table. Based on the fig. below, SM obtained from Ipomoea reniformis Choisy reduce DPPH radicals in concentration-dependent manner, data are expressed as mean±SD, n=3

Table 5: Effect of various extracts of Ipomoea reniformis choisy on IC50 values by DPPH scavenging activity

| S. No. | Extract/Standard | IC50 µg/ml |

| 1 | Chloroform extract | 59.05 |

| 2 | Ethyl Acetate extract | 91.92 |

| 3 | Ethanol Extract | 52.24 |

| 4 | Hydroalcoholic | 57.89 |

| 5 | Vitamin C (Standard) | 85. 08 |

Table 6: Represent pH values, consumed volume of artificial gastric juice ml and mmole of H+of Ipomoea reniformis choisy extract

| S. No. | Extract | pH value | Consumed volume of Artificial gastric juice ml | mmole of H+ |

| 1 | Water | 6.39 | 1.30±0.02 | 0.07±0.00 |

| 2 | Standard (SB) | 1.72 | 32.44±0.59 | 2.15±0.03 |

| 3 | Chloroform Extract (CE) | 1.54 | 7.24±0.08 | 0. 5±0.02 |

| 4 | Ethyl Acetate Extract (EA) | 1.56 | 9. 36±0.09 | 1.78±0.01 |

| 5 | Ethanol Extract (EE) | 1.69 | 10.56±0.09 | 1.56±0.01 |

| 6 | Hydroalcoholic Extract (HE) | 1.42 | 7.38±0.08 | 0.6±0.02 |

Data are presented as mean±SEM (N=3).

Acid neutralization capacity

The diluted extracts were estimated for their pH at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 37 °C. The pH value of CE was 1.54, EA was 1.56, EE was 1.69 and HE was 1.42. The pH value of water was 6.39; standard sodium bicarbonate (SB) was 1.72, determined for comparison. The consumed volumes of artificial gastric juices to titrate to pH 3.0 for water, sodium bicarbonate, CE, EE, EA and HE extract solutions were found to be 1.3±0.02, 32.44±0.59, 7.24±0.08, 10.56±0.09, 9.36±0.09 and 7.38±0.08, respectively. The neutralisation capacities of all the extracts accounted for the measure of the onset of action of antacids, since here the consumed volume of artificial gastric juice was lesser than that of sodium bicarbonate but significantly better than that of water. The consumed H+were 0.07±0.00, 2.15±0.03, 0.5±0.02, 1.78±0.01, 1.56±0.01 and 0.6±0.02 mmol, respectively. All the extracts exhibited significant antacid potency.

DISCUSSION

All of the extracts had neutralisation capabilities that were considerably higher than those of water but lower than those of sodium bicarbonate. Every extract showed a notable antacid potency. The artificial gastric acid neutralisation was higher with the ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts. The gastric acid neutralization can be possible in in vivo models too, as inhibition in acid secretion is achieved through various documented mechanisms, including competitive binding with adenosine triphosphate (ATP), affecting enzyme phosphorylation, and influencing the enzyme's conformation [23]. As this is a comparative study between four types of extract, the results suggest ethyl acetate and ethanolic extract of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy are more suitable for pharmacological effects that the plant phytoconstituents may possess.

CONCLUSION

Over the past few years, herbal drugs have gained a rich interest for medical use due to their less or no harmful reverse effect. The present phytochemical, in vitro antioxidant property and acid-neutralising potential investigation of various leaf extracts of Ipomoea reniformis Choisy highlights its significant medicinal potential, particularly in the treatment of ulcers. Based on the presence of bioactive compounds of the plant Ipomoea reniformis Choisy like flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, and phenols, correlates to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective properties. The ethnomedicinal potential of these herbs holds promise for the future of medicine and further studies might be carried out to explore the lead molecule responsible for aforesaid activity from this plant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Nil

FUNDING

Nil

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate, CE: Chloroform extract, EA: Ethyl acetate extract, EE: Ethanol extract, HE: Hydroalcoholic extract, DPPH: 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl, IC50: Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration, H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori, TS: Transverse Section

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Author 1: Anil Parasnath Sao: conceived and presented the idea, carried out literature collection using published articles from recent years, writing the manuscript using inputs data from all authors. Author 2: Kavita Loksh: supervised the finding of this review literature and finalized the content of this manuscript, discussed the results and commented on the manuscript, carried out the proofreading of the compiled manuscript. Author 3: Gaurav Jain: Conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. Author 4: Phoolsingh Yaduwanshi: Provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, discussed the results and commented on the manuscript for its intellectual content, carried out the proofreading of the compiled manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Bhardwaj S, Verma R, Gupta J. Challenges and future prospects of herbal medicine. Int Res in Med and Heal Sci. 2018 Oct 31;1(1):12-5. doi: 10.36437/irmhs.2018.1.1.D.

Sen S, Chakraborty R. Revival, modernization and integration of Indian traditional herbal medicine in clinical practice: importance, challenges and future. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017 Apr;7(2):234-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.05.006, PMID 28417092.

Kanwal H, Sherazi BA. Herbal medicine: trend of practice perspective and limitations in Pakistan. APJHS. 2017;4(4):6-8. doi: 10.21276/apjhs.2017.4.4.2.

Sharma R, Singla RK, Banerjee S, Sinha B, Shen B, Sharma R. Role of shankhpushpi (Convolvulus pluricaulis) in neurological disorders: an umbrella review covering evidence from ethnopharmacology to clinical studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;140:104795. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104795, PMID 35878793.

Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian medicinal plants. Bhuwaneswari Asrama (Bahadurganj, Allahabad): Sudhindra Nath Basu; 1918.

Abat JK, Kumar S, Mohanty A. Ethnomedicinal phytochemical and ethnopharmacological aspects of four medicinal plants of Malvaceae used in Indian traditional medicines: a review. Medicines (Basel). 2017 Oct 18;4(4):75. doi: 10.3390/medicines4040075, PMID 29057840.

Perez Jimenez J, Arranz S, Tabernero M, Diaz Rubio ME, Serrano J, Goni I. Updated methodology to determine antioxidant capacity in plant foods oils and beverages: extraction measurement and expression of results. Food Res Int. 2008 Mar;41(3):274-85. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.12.004.

Kukreti N, Rani R, Varshney VK, Chitme HR. Important medicinal plants recommended in management of rheumatoid arthritis. Bangla Pharma J. 2022 Jul;25(2):125-36. doi: 10.3329/bpj.v25i2.60964.

Babini CK, Reena A. Phytochemical screening and determination of antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activity of Ulva lactuca-based silver nanoparticle. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024 Dec;17(12):45-53. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024v17i12.52755.

Cope JS, Corney D, Clark JY, Remagnino P, Wilkin P. Plant species identification using digital morphometrics: a review. Expert Syst Appl. 2012 Jun 15;39(8):7562-73. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2012.01.073.

Kumar A, Singh L. Pharmacognostic study and development of quality control parameters for whole plant of Acampe papillosa Lindl. Neuro Quantology. 2022;20(15):5614-22.

Groth Helms D, Rivera Y, Martin FN, Arif M, Sharma P, Castlebury LA. Terminology and guidelines for diagnostic assay development and validation: best practices for molecular tests. Phyto Frontiers. 2023 Jun 22;3(1):23-35. doi: 10.1094/PHYTOFR-05-22-0059-FI.

Subbulekshmi KO, Godwin SE, Vahab AA. Phytochemical and in vitro antioxidant activity of ethanolic extract of Strobilanthes barbatus nees leaves. Asian J Pharm Res Dev. 2015 Mar;3(2):13-20.

Kumari K, Gilhotra UK, Chawla R. Phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis of natural plant extract of Dalbergia sissoo, Hibiscus rosa, and Quisqualis indica. Front Health Inform. 2024 Apr 1;13(3):e13.

Khare P, Khare N. Memory-enhancing activity of Madhuca longifolia ethanolic leaf extract (flavonoid fraction) and its HPTLC. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2023 Mar;15(2):51-8. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2023v15i2.2097.

Perez Jimenez J, Arranz S, Tabernero M, Diaz Rubio ME, Serrano J, Goni I. Updated methodology to determine antioxidant capacity in plant foods oils and beverages: extraction measurement and expression of results. Food Res Int. 2008 Mar;41(3):274-85. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.12.004.

Jaradat NA, Zaid AN, Abuzant A, Shawahna R. Investigation the efficiency of various methods of volatile oil extraction from Trichodesma africanum and their impact on the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. 2016 May;5(3):250-6. doi: 10.5455/jice.20160421065949, PMID 27366351.

Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152-78. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1.

Quettier Deleu C, Gressier B, Vasseur J, Dine T, Brunet C, Luyckx M. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) hulls and flour. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72(1-2):35-42. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00196-3, PMID 10967451.

Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181(4617):1199-200. doi: 10.1038/1811199a0.

Permata YM, Laila L, Yuliasmi S, Theresia L, Wijaya V. Potentiality of protein hydrolysate from Anadara granosa as nutraceutical agent: antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(6):264-70. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.51482.

Usnale SV, Garad SV, Panchal CV, Poul BN, Dudhamal SS, Thakre CV. Pharmacognostical studies on Ipomea reniformis chois. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2009;1(2):65-7.

Raghuvanshi A. Phytochemical and antioxidant evaluation of Ipomoea reniformis. Int J Green Pharm. 2017;11(3):S575-8. doi: 10.22377/ijgp.v11i03.1176.

Cheng A, Carlson GM. Competition between nucleoside diphosphates and triphosphates at the catalytic and allosteric sites of phosphorylase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(12):5543-9. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60598-8, PMID 3356697.