Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 10, 27-32Original Article

DEVELOPMENT AND CHARACTERIZATION OF VALUE-ADDED FOOD COLOURANT DERIVED FROM SOLUBLE DIETARY FIBER OF POMEGRANATE PEEL AND ONION PEEL

MOUSUMI DASa*, ASMITA BHATTACHARJEEa’b

Department of Applied Nutrition and Dietetics, Sister Nivedita University, DG Block (Newtown), Action Area I, 1/2, Newtown-700156, Chakpachuria, West Bengal, India

*Corresponding author: Mousumi Das; *Email: das.musumi2001@gmail.com

Received: 10 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 19 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This research focuses on effective global food waste management strategies while exploring the sustainable use of agricultural waste through the extraction of soluble dietary fiber (SDF) from onion peels (O-SDF) and pomegranate peels (P-SDF) to produce a natural food colourant with added value.

Methods: Pomegranate and onion peels were harvested and pre-processed before being subjected to an alkali extraction method to extract SDF. The research employed FT-IR spectroscopy, in conjunction with evaluations of water and oil holding capacity, and assessments of total phenol, flavonoid, and tannin content, as well as DPPH radical scavenging activity, anthocyanin content analysis, and color measurements, to examine the extracted SDF.

Results: The peel of pomegranates allowed the isolation of 3-4 g of SDF, but onion peels yielded only 1-2 g of SDF. The SDF derived from onion peel exhibited greater phenol content of 140.32 mg GAE/100g and flavonoid and tannin levels of 62.41 mg RE/100g and 54.67 mg TAE/100g, respectively, compared to pomegranate peel SDF, while also demonstrating superior water holding capacity at 2.95 g/g. Onion peel SDF demonstrated an IC50 value of 778.81 µg/ml, while pomegranate exhibited an IC50 value of 390.62 µg/ml for DPPH radical scavenging activity. The colour analysis revealed that both samples exhibited bright yellow colours along with identical chroma values.

Conclusion: The research demonstrates potential applications for repurposing fruit and vegetable waste into natural food colourants that exhibit potent antioxidant properties. This approach enables the creation of eco-friendly food additives by converting agricultural waste into high-value products that support the circular bioeconomy and sustainable waste management systems.

Keywords: SDF, Pomegranate peel, Onion peel, Food colourant, Waste valorisations, Antioxidants, Natural pigments, Sustainable agriculture, Circular bioeconomy, Food technology

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i10.56483 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Food waste is a global challenge that occurs at various stages of food production, processing, marketing, and consumption. Chronic open burning or uncured disposal of these wastes leads to the emission of toxic gases, organic pollutants, and nutrients, thereby causing air, water, and soil pollution, eutrophication, and other problems. The additional population and food requirements escalate food wastage, pollution, and financial losses. To address these requirements, it is essential to boost food availability while simultaneously decreasing food loss and wastage. [1]. Valorisation routes for these wastes include thermochemical (combustion, pyrolysis, gasification) and biochemical routes, including hydrothermal conversion and biorefinery approaches. Integrated biorefineries can enhance the sustainable extraction of biofuels, biochemicals, and biofertilizers from wastes using physical, chemical, and biological treatment methods in an eco-friendly manner. This circular bioeconomy is enhanced with multi-feedstock biorefineries that address the problem of agro-waste by transforming it into renewable energy resources [2].

Approximately 50% of fruit and vegetable waste consists of outer peels that contain abundant dietary fiber, natural pigments, and minerals. The pigments above are green and contribute numerous benefits to our health, like strengthening the immune system and improving the complexion of the skin [3]. Extracting food additives and pharmaceuticals from fruit and vegetable waste helps in reducing the overall waste produced and preserving the environment. Cumulatively, the most significant pigments include carotenoids, which yield red, yellow, and orange (e. g., apricot and tomato), and citrus, contributing yellow, as well as anthocyanidins, contributing red, purple, and blue. The pigments demonstrate strong antioxidant activity and provide multiple health benefits, including anti-aging effects, nervous system repair, and protective action against atherosclerosis, cancer, inflammatory conditions, and other aging-related disorders [3, 4].

A byproduct of the juice industry is pomegranate peel (PoP). Pomegranate peel constitutes about 50% of the fruit weight and contains various compounds, including phenolics, polysaccharides, flavonoids, and microelements [5]. Pomegranate peel attracts attention due to its wound healing, antimicrobial, immune-modulatory, and antioxidative properties. The peel offers weight-boosting and health-enhancing effects without the detrimental effects of antibiotics and hormones, resulting in meat with higher levels of beneficial antioxidants [6]. Pomegranate peel contains natural compounds that improve skin health by reducing pigmentation, fighting inflammation, and warding off fungal infections [7]. Lab tests show pomegranate skin extract contains compounds that may block COVID-19 from attaching to human cells, potentially helping prevent infection [8]. Additionally, starch, pectin, and fiber present in the PoP have been shown to improve the plasticizing effect and flexibility of mung bean protein films [9].

Every day, a huge amount of onion peels/skin is generated either at the household kitchen or industrial level. These wastes contain rich sources of bioactive compounds, such as phenols and flavonoids and are also packed with fiber, natural sweeteners, and sulfur compounds that could boost your health, making them valuable ingredients worth saving rather than tossing. Onion wastes can be used as food ingredients because of its fructooligosaccharides, and alk(en)yl cysteine sulphoxides [10]. The medicinal and pharmaceutical uses of onion residue and its extracts can also be fruitful in minimizing ecological damage and offer an affordable alternative for the development of therapeutic enhancements or herbal products [11]. Allium compounds prevent blood clots, potentially boosting heart health [12].

In recent days, it has become a huge problem of waste disposal, especially in urban areas [1]. Therefore, it is challenging to properly utilize by-products, aiming for environmental protection.

In this recent study, an attempt has been made to utilize the pomegranate peel and onion peel as a value-added natural food colourant derived from the SDF of pomegranate peel and onion peel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of plant material

Specimens of Punica granatum (pomegranate) and Allium cepa (red onion) were collected from the local Beliaghata market, Kolkata, West Bengal. All of the specimens are identified with the help of systematic morphological characteristics, which are related to the standard taxonomical procedures.

The GPS coordinates of the place are

Location: Sarkar Bazaar, Beleghata, Kolkata.

Address: Beleghata Main Road, Beliaghata, Kolkata-700010.

Coordinates: 22.570212°N 88.382189°E.

Regarding the identification process of Punica granatum (pomegranate), this fruit belongs to the Lythraceae family. Important findings involve leathery characteristics, leaves are opposite with entire margins, and clear tubular calyx with 5-7 lobes. Crumbled petals with various stamens as well as multilocular ovaries were observed, which gives the crowned shape to the fruit along with the persistent calyx lobes.

The Allium cepa red variant, from the family Amaryllidaceae, is identified through its bulbous underground storage organ with papery red-purple outer scales, hollow cylindrical leaves (pseudostems), umbellate inflorescence when allowed to flower, and the characteristic pungent sulfur compounds that produce the typical onion odour when tissues are damaged.

Chemicals and reagents

Sodium hydroxide, ethanol, sodium carbonate, Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent, gallic acid, Rutin, aluminium chloride, NaNO2, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazine (DPPH), sodium acetate, potassium chloride, HCL, ascorbic acid, tannic acid, deionized water, sunflower oil.

Pretreatment of pomegranate peel and onion peel

Both of the peels were first separated and washed properly. Cut the peels into very small pieces and weigh the total amount of peel before freeze-drying. Then the peels were freeze-dried for 16 h. After drying, the peels were pulverized with a high-speed crusher and then passed through a 60-mesh screen. The prepared sample was then stored in a zip-lock bag at room temperature for further analysis [13].

Alkali extraction of SDF

10 g of powdered pomegranate peel and powdered onion peel were blended into 150 ml of sodium hydroxide solution (1%, w/w) separately and stirred at ambient temperature for 2 h. Then the mixture was centrifuged at 4000×g for 20 min. The centrifuged supernatant was concentrated before precipitating with ethanol and treated with vacuum freeze drying [14]. After drying, the samples were stored at 4 ℃ for further analysis.

FT-IR analysis

Approximately 1 mg of KBr and 99 mg of sample were ground thoroughly and mixed well with each other. The mixture was pressed into pallets. The thickness of the pallet should be 1-2 cm. This pallet was assayed by using an FT-IR spectrometer (IRSpirit, Shimadzu Corp.) in the wavenumber range of 4500-500 cm-1.

Water holding capacity (WHC)

0.2g sample is weighed (W1), add in 5 ml of distilled water is added and mixed properly. Then incubate at 25℃ for 2h and centrifuge at 1000×g for 20 min. The sediment was collected and weighed (W2) [15].

Oil holding capacity (OHC)

0.5 g of samples were accurately weighed (W) in a previously weighed centrifuge tube. 5 ml of sunflower oil was added and mixed. Tubes were left standing at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were centrifuged at 4200 rpm for 15 min [16]. Sediment was weighed (W1), and OHC was calculated according to the following formula:

Preparation of hydroethanolic extracts

The sample extract was prepared for the antioxidant content and DPPH radical scavenging activity by weighing 250 mg (25 mg/ml) and 10 mg (1 mg/ml) of the sample, and mixed with 10 ml of 80% ethanol. Then the mixture was ultrasonicated for 20 min to reduce the particle size. Then it was centrifuged at 8944×g for 10 min at 4℃. Then the supernatant and stored and ready for use [17].

For the determination of total anthocyanin content, 1g of sample was taken and mixed with 10 ml ethanol: 0.1 M HCL (85:15 %, v/v) and sonicated for 10 min. Then it was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and used for anthocyanin determination [18].

Total phenol content (TPC)

The total phenol content of the sample was determined spectrophotometrically using the Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent. 1 ml of different concentrations (0.2,0.4,0.6,0.8,1) of hydroethanolic extract (25 mg/ml) and gallic acid (standard) were diluted to make up the volume up to 2 ml and were mixed with Folin--Ciocalteu reagent (0.2 ml, 1:10 diluted with distilled water). Then 2 ml of 7% aqueous sodium carbonate was added, and the volume brought up to 5 ml. After 90 min of incubation, the absorbance was measured at 750 nm [17].

Total flavonoid content (TFC)

Total flavonoid content was determined by aluminium chloride spectrophotometric assay [19]. Hydro-ethanolic extract (25 mg/ml) and standard rutin solution (1 mg/ml) of different concentrations (0.2,0.4,0.6,0.8,1) were added in volumetric flasks and made up the volume with ethanolic water up to 1 ml. After that, 4 ml of distilled water was added. To the above mixture, 0.3 ml of 5% NaNO2 was added (incubate for 5 min), 0.3 ml of 10% AlCl3 was added (incubate for 6 min), and 2 ml of NaOH solution was added. Then the total volume was made up to 10 ml with distilled water, and the solution was mixed well. After 5 min of incubation, the absorbance was measured at 510 nm.

Total tannin content

The total phenol content of the sample was determined spectrophotometrically using the Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent [20]. 1 ml of different concentrations (0.2,0.4,0.6,0.8,1) of hydro-ethanolic extract (25 mg/ml) and standard tannic acid solution (1 mg/ml) were taken in a volumetric flask. Then 7.5 ml of distilled water and 0.5 ml of FC reagent (1:10) were added and mixed properly. After that, 1 ml of 35% sodium carbonate solution was added, and the volume was brought up to 10 ml. The mixture was shaken well and kept at room temperature for 30 min. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 700 nm.

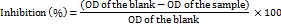

Total anthocyanin content (TAC)

Total anthocyanin content is determined by the pH differential method. 3 ml of the extract is diluted in 5 ml of two different buffers: 0.025 M potassium chloride buffer (pH 1.0) and 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5), respectively. Then incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and the OD at 510 nm and 700 nm was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer [18].

For the calculation of total anthocyanins, as:

Calculate the monomeric anthocyanin pigment concentration in the original sample using the formula:

And it was converted to mg of total anthocyanin content/100 g sample.

Where Asp is the absorption of the sample, MW is molecular weight = 449.2 g/mol [21], DF is the dilution factor, ε is the molar coefficient = 26900 [21], λ is the cuvette optical pathlength (1 cm), and m is the weight of the sample.

DPPH radical scavenging activity

1 ml of various concentrations of the prepared hydroethanolic extract was taken in a different test tube and made up the volume to 1 ml with ethanol. Blank was prepared using 1 ml of ethanol. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard. 0.1 mmol of ethanolic DPPH solution (22.2 mg in 1000 ml) was freshly prepared. Then add 2 ml of ethanolic DPPH solution and mix well. Incubate for 30 min at room temperature in a dark place and measure OD at 517 nm against distilled water using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer [22, 23]. An IC50 value was calculated as the concentration that brought about a 50% reduction in absorbance compared to the blank.

Colour determination

The HunterLab l, a*, b*, and the CIELAB modified system, known as CIELAB colour scales, were opponent-type systems widely applied in the food industry. The CIELAB coordinates (L*, a*, b*) were read directly. It was regarded as a CIELAB uniform space where two colour coordinates, a* and b*, and a psychometric index of lightness, L, were measured. The parameter a* is positive for reddish colours and negative values for greenish ones, while b* has positive values for yellowish colours and negative values for bluish ones. L is a rough measure of luminosity, the property by which each colour can be regarded as equivalent to a member of the greyscale, between white and black [24, 25].

Chroma (C*) represents the measurable characteristic of the concept of colourfulness and serves as a metric to assess how much variation exists between visual elements, about a grey colour with the same lightness. The relationship between chroma values and their magnitude shows direct proportionality. The perception of sample colour intensity by human observers.

Hue angle (h*) represents a qualitative attribute of colour that stands as the defining label for colours as reddish and greenish among other hues, and it is used to define the difference of a certain colour from the grey colour, maintaining identical lightness levels. This attribute is related to the variations in light absorption across multiple wavelengths.

0˚ or 360˚ represents red hue, 90˚, 180˚ and 270˚ represents yellow, green and blue hues respectively.

When materials are exposed to light, chemicals, or processing, they often develop an unpleasant yellow tint. This yellowing is typically a sign of damage or aging, indicating that the material has undergone some form of degradation. Yellowness indices are used as a quick and easy way to measure this discoloration. These indices provide a single, straightforward number that captures the extent of yellowing. They're particularly useful for analysing transparent liquids or nearly white, opaque materials, allowing researchers to track changes in colour and quality over time [26].

Y1 = 142.86b*/l

RESULTS

Alkali extraction of soluble fiber

3-4 g of SDF (P-SDF) was extracted from 10 g of pomegranate peel powder, and 1-2 g of SDF (O-SDF) was extracted from onion peel powder.

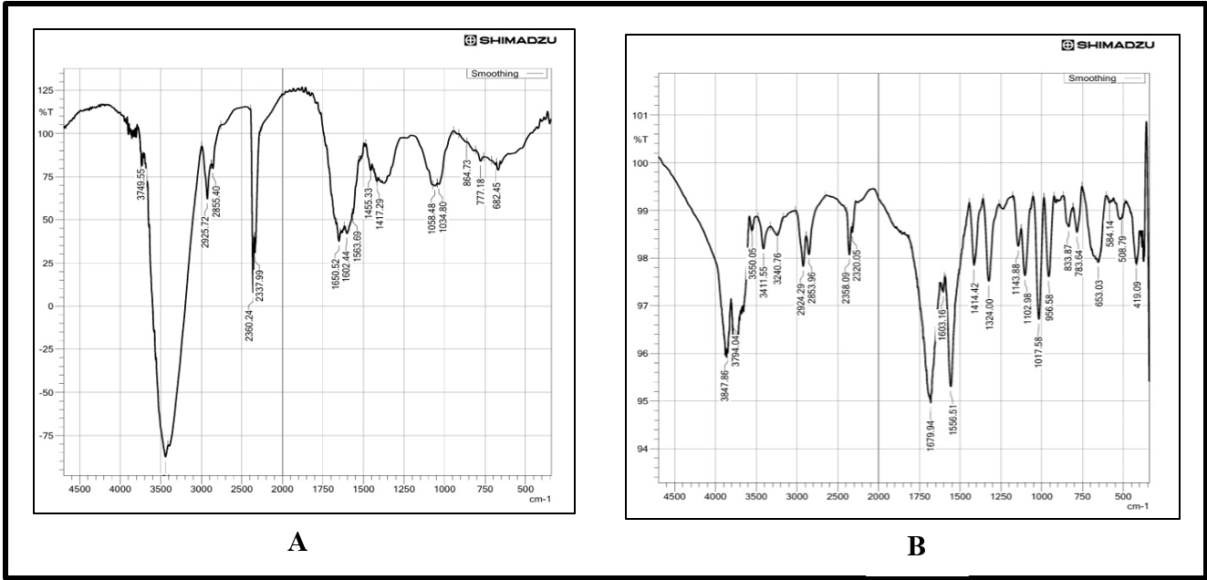

FT-IR analysis

The FTIR spectrum shows the organic molecular profile of the sample under investigation as quite intricate, revealing distinct peaks with important features. Some crucial functional groups and molecular linking over a wavenumber span are indentified by the spectrum analysis. Both of the spectra display different ranges of transmittance, P-SDF shows approximately 90%-125 %, and O-SDF shows about 94% to 101%. This indicates that O-SDF is much less intense compared to the P-SDF. A peak of 2925.72 cm⁻¹ and 2924 cm⁻¹ is the indicator of saturated hydrocarbon chains and shows aliphatic C-H stretching vibrations. According to the structure of polystyrene, vibrational bands of around 1602.44 cm⁻¹ and 1603 cm⁻¹ suggest the presence of C6H5 moieties, that is, benzene-like structures which are attributed to aromatic ring vibrations. Important absorption bands at 3749.55 cm⁻¹ and 3847 cm⁻¹ surface hydroxyl may potentially be indicative of surface bonds or the attachment of some residual water. Spectra also have dips of low intensity at 2358 cm⁻¹ and 2337.99 cm⁻¹, which might be molecular overtones or interference from CO2. Out-of-plane aromatic C-H bending at 864.73 cm⁻¹ confirms the out-of-plane C-H bending of the aromatic ring, and this has been confirmed by the spectral data at hand. The peaks evidence greater shallow and structural changes of the molecular composition identification polymer have distinct and few features, organic changes of advanced resultant structural, termed thus organic polymer.

Fig. 1: FT-IR spectra of P-SDF (A) and O-SDF (B)

Water holding capacity and oil holding capacity

There is no water-holding capacity for P-SDF, but the WHC of O-SDF is 2.95 g/g.

The OHC of P-SDF is 3.9 g/g and 4.9g/g for O-SDF.

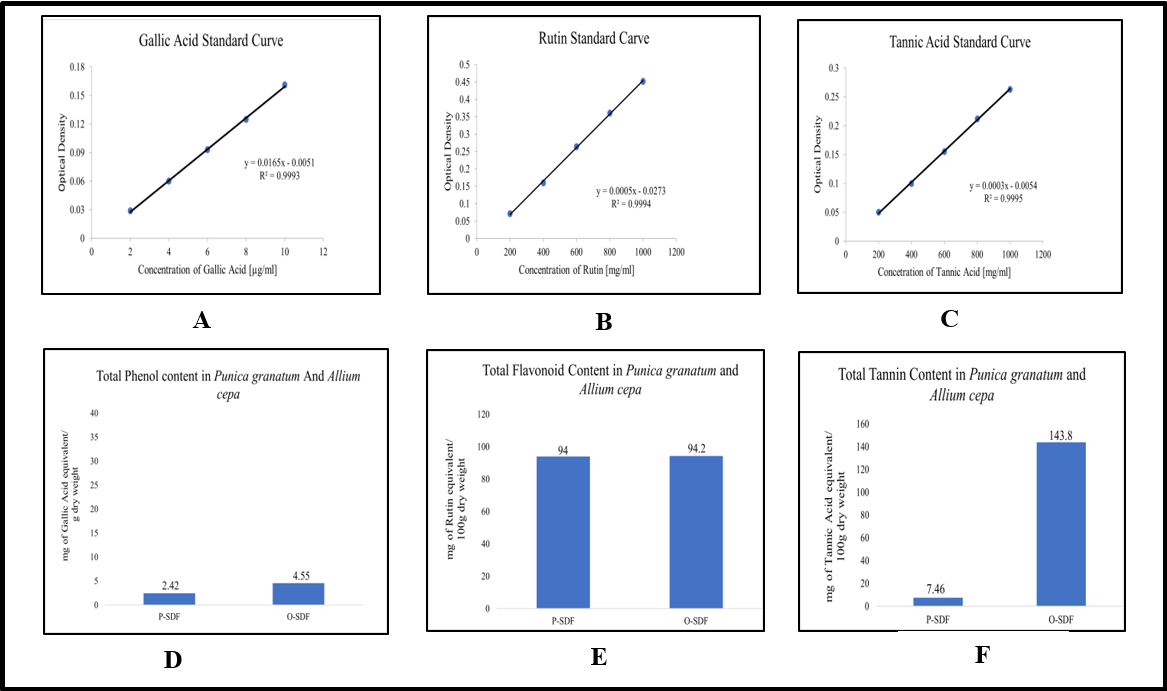

Total phenol, flavonoid and tannin content

TPC of both extracts of the samples is estimated as gallic acid equivalent/100g dry weight of the samples. The phenol content of O-SDF is slightly higher than P-SDF.

TFC of both extracts of the samples is expressed as rutin equivalent/100g dry weight of the samples. The flavonoid content of O-SDF is found to be higher than P-SDF.

The tannin content of both extracts of the samples is estimated as tannic acid equivalent/100g dry weight of the samples. The tannin content of O-SDF is much higher than P-SDF.

Fig. 2 below represents the total phenol, flavonoid, and tannin content of pomegranate (P-SDF) and onion (O-SDF) along with standard curves of gallic acid, rutin and tannic acid, respectively.

Fig. 2: Total phenol, flavonoid, and tannin content of Punica granatum and Allium cepa, A, B and C: standard curves of gallic acid, rutin, and tannic acid, respectively. D, E and F: The total phenol, flavonoid and tannin content of the extract of pomegranate (P-SDF) and onion (O-SDF), respectively. All data are expressed as mean±SD of a triplicate set of values (n=3)

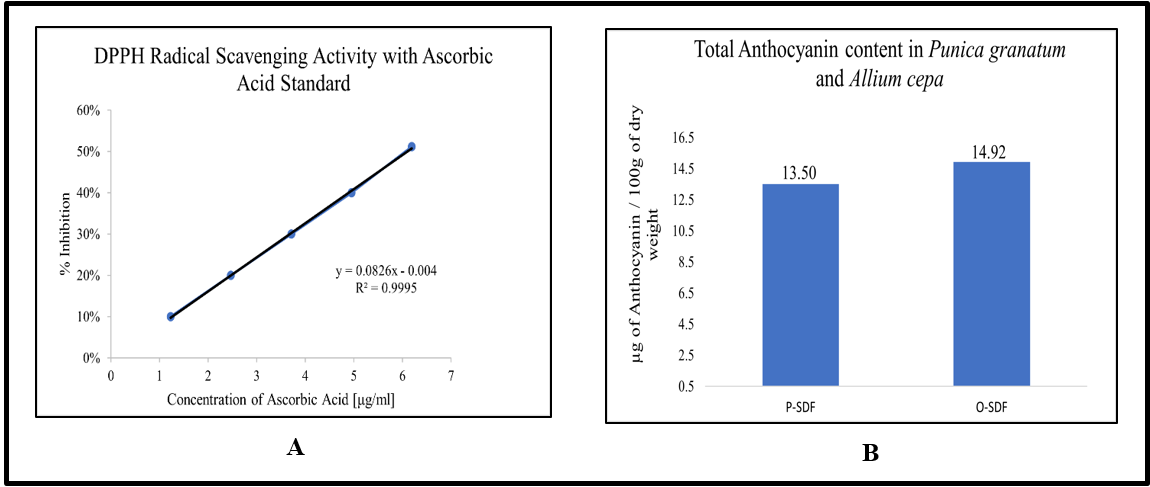

Fig. 3: A: Standard curve for ascorbic acid for DPPH radical scavenging activity, B: Total anthocyanin content of the extract of Punica granatum and Allium cepa. The data of DPPH is expressed as mean±SD of a triplicate set of values (n=3)

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The antioxidant activity of the extract of Punica granatum and Allium cepa was measured by 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity.

The IC50 value of P-SDF extract is 390.62 µg/ml, and for O-SDF extract, the IC50 value is 778.81 µg/ml.

Fig. 3 below shows the standard curve of ascorbic acid.

Total anthocyanin content

Anthocyanin content in both extracts of fresh samples is estimated as mg of total anthocyanin content/100g dry sample.

100g of fresh pomegranate (P-SDF) yields 13.50 µg of anthocyanin, and an onion (O-SDF) contains 14.92 µg of anthocyanin.

Colour determination

With the measurements, both samples display features that strikingly compare with subtle differences.

The saturation of any given colour is represented by its chroma. In colour theory, high chroma values are associated with pure, vibrant colours, whereas low values suggest subdued or greyish tones. A moderately saturated colour is represented by the 66 values (O-SDF), while the 61.65 (P-SDF) shine or saturation value suggests a brightly coloured metric.

Usually, the hue angle labelled is measured in degrees (0-360) around the horizon of a colour wheel. The hue angles for both samples, 53.63° (P-SDF) and 48.72° (O-SDF), indicate a strong signal around the yellow region of the spectrum for both samples.

A specific metric called the Yellowness Index is often used to measure the extent to which yellowing has occurred over time or to quantify the intensity of yellowing within industries such as food, textiles, and plastics. P-SDF and O-SDF values of 173.90 and 183.40, respectively, are quite high and demonstrate strong yellow effects.

DISCUSSION

The study emphasizes the technology of food that provides sustainable solutions as well as the circular bio-economy, in recognition of the fact that the waste from agriculture can be converted into valuable materials. The yields were mainly influenced by the differences found in the cell walls of plants, leading to a wide gap in the performance of pomegranate peels, mainly due to their high pectin and soluble fibre content, which is characteristic of economic and industrial scaling demand.

Research results from both oil-holding capacity (OHC) tests and water-holding capacity (WHC) tests of the extracts show the wide applicability of these extracts. O-SDF had a WHC of a staggering 2.95 g/g, representing a very high level of water retained, which allows the colourant to be compatible with the food products needing the highest water retention, e. g., the daily meat-processing and baking industry. The OHC tests also revealed good values for the extracts, which for P-SDF was 3.9 g/g, and for O-SDF, 4.9 g/g. In simple terms, this finding means that the two extracts can solve the issue of fine texture and be used as dispersion agents in the case of food products with low-fat content. For instance, a good mouthfeel in food is paramount.

As for polyphenols, even though O-SDF had significantly higher amounts of total phenolic, flavonoid, and tannin compounds, P-SDF displayed more than double the antioxidant activity of O-SDF. This shows that there is a close relationship between the properties where the structure affects activity and vice versa. The reason for the increased level of antioxidants in P-SDF is that some exclusive compounds, like punicalagin, are present.

Colour measurement results show interesting similarities and some differences in the pomegranate and onion peel-soluble fiber. Both samples had a yellow pigment, but the chroma was nearly the same, which shows that the colour intensity was also equal in both samples, but with a different source. Both extracts were firmly categorized into the yellow region of colour and the wheel according to their hue angles, which is in line with their respective yellowness indices. O-SDF would potentially contribute a marginally greater level of yellow pigmentation than P-SDF when used as a food add-in, which is consistent with this slightly higher yellowness index across the same panel. The findings on colour properties, and antioxidant and functional capacities research conducted in this study, suggest potential for these agricultural by-products to be used for food technology applications in a circular bioeconomy context or framework.

This work demonstrates unique aspects from other similar research in that it emphasizes both colour yield potential and functional properties. Hussain et al. investigated extracts of pomegranate peel primarily for their antibacterial nature and not as a food supplement [27], whereas Tunchaiyaphum et al. applied microwave heating for pectin extraction from lime peels without studying colourant uses [28]. The findings of this study are in agreement with the observations made by G. Karthikeyan et al. observed similar findings regarding the free radical scavenging ability of pomegranate peel extract [29]. The pomegranate extract is particularly rich in antioxidants. This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of onion peel and its capacity to retain water and oil, and thus it is preferable to SP Chiew et al., who focused on the phytochemicals, antibacterial, and cytotoxic potential of onion peel [30]. Furthermore, the study's FTIR examination of structural features provides a more in-depth understanding than the simpler extraction techniques used in Venkataramanamma et al.'s work on fruit peel colourants [31]. The study offers more comprehensive information for possible commercial applications than many similar studies, contributing useful data on both functional and sensory qualities.

CONCLUSION

The present study concludes that this domain could be directed toward upscaling the extraction and characterization of SDF from Punica granatum and Allium cepa peels toward sustainable food colourants at an industrial scale. Further research could look into optimizing extraction strategies to increase yield and purity, potential synergies associated with the use of different agricultural waste streams, and stability, sensory, and storage stability studies associated with these natural colourants. This new approach can help in economic improvements and contribute to the solution of the economic problems associated with the generation of waste. The findings in the research also give an example of a sustainable business. The problem of pomegranate and onion peels in terms of waste management comes from their frequent presence as agricultural by-products, with food processors producing more peels as the demand for them increases. Accordingly, the companies that carry out waste management through food ingredient development are hailed as the ones having high environmental and social responsibility. The selling point for these extracts is that they possess the colourant and bioactive compound qualities, thus targeting the growing clean-label food market. Likely, these results will also benefit the nutraceutical and cosmetic industries, where the demand for natural colourants and antioxidants is high and increasing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Assistant Professor Ms. Asmita Bhattacharjee and HOD Dr. Moumita Das, Department of Applied Nutrition and Dietetics, as well as Sister Nivedita University, for providing the necessary infrastructure and support to conduct this research.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Mousumi Das: Investigation, study, validation. Asmita Bhattacharjee: Conceptualization, supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

1. Gupta N, Poddar K, Sarkar D, Kumari N, Padhan B, Sarkar A. Fruit waste management by pigment production and utilization of residual as bioadsorbent. J Environ Manage. 2019 Aug 15;244:138-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.055, PMID 31121500.

2. Singh R, Das R, Sangwan S, Rohatgi B, Khanam R, Peera SK. Utilisation of agro-industrial waste for sustainable green production: a review. Environmental Sustainability. 2021;4(4):619-36. doi: 10.1007/s42398-021-00200-x.

3. Cortez R, Luna Vital DA, Margulis D, Gonzalez De Mejia E. Natural pigments: stabilization methods of anthocyanins for food applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2017;16(1):180-98. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12244, PMID 33371542.

4. Fernandes AC, Mateus N, De Freitas V. Polyphenol dietary fiber conjugates from fruits and vegetables: nature and biological fate in a food and nutrition perspective. Foods. 2023 Mar 1;12(5):1052. doi: 10.3390/foods12051052, PMID 36900569.

5. Akhtar S, Ismail T, Fraternale D, Sestili P. Pomegranate peel and peel extracts: chemistry and food features. Food Chem. 2015 May 1;174:417-25. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.035, PMID 25529700.

6. Ranjitha J, Bhuvaneshwari G, Terdal D, Kavya K. Nutritional composition of fresh pomegranate peel powder. Int J Chem Stud. 2018 Jun 8;6(4):692-6.

7. Yoshimura M, Watanabe Y, Kasai K, Yamakoshi J, Koga T. Inhibitory effect of an ellagic acid-rich pomegranate extract on tyrosinase activity and ultraviolet-induced pigmentation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005 Jan 1;69(12):2368-73. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2368, PMID 16377895.

8. Tito A, Colantuono A, Pirone L, Pedone E, Intartaglia D, Giamundo G. A pomegranate peel extract as inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Spike binding to human ACE2 (in vitro): a promising source of novel antiviral drugs. bioRxiv. 2020 Dec 1. doi: 10.1101/2020.12.01.406116.

9. Moghadam M, Salami M, Mohammadian M, Khodadadi M, Emam Djomeh Z. Development of antioxidant edible films based on mung bean protein enriched with pomegranate peel. Food Hydrocoll. 2020 Jul;104:105735. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105735.

10. Griffiths G, Trueman L, Crowther T, Thomas B, Smith B. Onions a global benefit to health. Phytother Res. 2002 Oct 30;16(7):603-15. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1222, PMID 12410539.

11. Kumar M, Barbhai MD, Hasan M, Punia S, Dhumal S, Radha RN. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peels: a review on bioactive compounds and biomedical activities. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Feb;146:112498. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112498, PMID 34953395.

12. Mallor C, Thomas B. Resource allocation and the origin of flavour precursors in onion bulbs. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2008;83(2):191-8. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2008.11512369.

13. Mphahlele RR, Fawole OA, Makunga NP, Opara UL. Effect of drying on the bioactive compounds antioxidant, antibacterial and antityrosinase activities of pomegranate peel. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:143. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1132-y, PMID 27229852.

14. Xiong M, Feng M, Chen Y, Li S, Fang Z, Wang L. Comparison on structure properties and functions of pomegranate peel soluble dietary fiber extracted by different methods. Food Chem X. 2023 Oct 30;19:100827. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100827, PMID 37780339.

15. Wang S, Fang Y, Xu Y, Zhu B, Piao J, Zhu L. The effects of different extraction methods on physicochemical functional and physiological properties of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber from Rubus chingiiHu. fruits. J Funct Foods. 2022 Jun;93:105081. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105081.

16. Perez Pirotto C, Moraga G, Quiles A, Hernando I, Cozzano S, Arcia P. Techno functional characterization of green extracted soluble fibre from orange by product. LWT. 2022 Aug 16;166:113765. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113765.

17. Ray S, Saha SK, Raychaudhuri U, Chakraborty R. Preparation of okra incorporated dhokla and subsequent analysis of nutrition antioxidant color moisture and sensory profile. Food Measure. 2017;11(2):639-50. doi: 10.1007/s11694-016-9433-x.

18. Tonutare T, Moor U, Szajdak L. Strawberry anthocyanin determination by pH differential spectroscopic method how to get true results? Acta Sci Pol Hortorum Cultus. 2014;13(3):35-47.

19. Kumar S, Kumar D, Manjusha, Saroha K, Singh N, Vashishta B. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. methanolic fruit extract. Acta Pharm. 2008;58(2):215-20. doi: 10.2478/v10007-008-0008-1, PMID 18515231.

20. Plakantonaki S, Roussis I, Bilalis D, Priniotakis G. Dietary fiber from plant-based food wastes: a comprehensive approach to cereal fruit and vegetable waste valorization. Processes. 2023;11(5):1580. doi: 10.3390/pr11051580.

21. Sutharut J, Sudarat J. Total anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity of germinated coloured rice. Int Food Res J. 2012;19(1):215-21.

22. Sreejayan N, Rao MN. Free radical scavenging activity of curcuminoids. Arzneimittelforschung. 1996;46(2):169-71. PMID 8720307.

23. Mohammad TA. Determination of polyphenolic content and free radical scavenging activity of Flemingia strobilifera. Adv Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;10:89-95.

24. Granato D, Masson ML. Instrumental color and sensory acceptance of soy-based emulsions: a response surface approach. Ciênc Tecnol Aliment. 2010;30(4):1090-6. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612010000400039.

25. Pathare PB, Opara UL, Al Said FA. Colour measurement and analysis in fresh and processed foods: a review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013;6(1):36-60. doi: 10.1007/s11947-012-0867-9.

26. Rhim JW, Wu Y, Weller CL, Schnepf M. Physical characteristics of a composite film of soy protein isolate and propylene glycol alginate. J Food Sci. 1999;64(1):149-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1999.tb09880.x.

27. Tunchaiyaphum S, Eshtiaghi MN, Yoswathana N. Extraction of bioactive compounds from mango peels using green technology. Int J Chem Eng Appl. 2013;4(4):194-8. doi: 10.7763/IJCEA.2013.V4.293.

28. Hussain A, Albasha F, Siddiqui NA, Husain FM, Kumar A, AlGhamdi KM. Comparative phytochemical and biological assessment of Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel extracts at different growth stages in the Taif region Saudi Arabia. Nat Prod Res. 2024 Dec 27:1-10. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2024.2440931, PMID 39727256.

29. Chiew SP, Thong OM, Yin KB. Phytochemical composition antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of red onion peel extracts prepared using different methods. Int J Integr Biol. 2014;15(2):49-54.

30. Karthikeyan G, Vidya AK. Phytochemical analysis antioxidant and antibacterial activity of pomegranate peel. Res J Life Sci Bioinform Pharm Chem Sci. 2019;5(1):218. doi: 10.26479/2019.0501.22.

31. Venkataramanamma D, Aruna P, Singh RP. Standardization of the conditions for extraction of polyphenols from pomegranate peel. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53(5):2497-503. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2222-z, PMID 27407217.