Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 12, 27-35Original Article

BIOACTIVE POTENTIAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICINAL PLANT ASPARAGUS SUAVEOLENS: PHYTOCHEMICAL SCREENING, ANTIOXIDANT, AND ANTIBACTERIAL ACTIVITIES

HNE MASHILOANE1, MT OLIVIER2, NS MAPFUMARI3*, SS GOLOLO1

1Department of Biochemistry, School of Science and Technology, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa. 2Department of Chemistry, School of Science and Technology, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa. 3Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa

*Corresponding author: NS Mapfumari; *Email: Sipho.mapfumari@smu.ac.za

Received: 10 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 18 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the phytochemical composition, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities of root extracts of A. suaveolens.

Methods: The roots of A. suaveolens were collected from Bolahlakgomo village in Zebediela subregion, Limpopo province (South Africa) and ground into powder after drying. The ground plant material was extracted sequentially with hexane, dichloromethane (DCM), methanol (MeOH), and water (H2O). The resultant extracts were then subjected to phytochemical screening, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) fingerprinting, and gas chromatography – mass spectrometry (GC–MS) for the detection of different classes of compounds. Antioxidant activity was assessed using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl(DPPH) free radical scavenging, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) scavenging, and ferric chloride (FeCl3)reducing power assays. Antibacterial activity was evaluated against four pathogenic bacterial strains (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus pyogenes) using a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay and TLC-bioautography.

Results: Extraction with methanol yielded the highest extract mass, followed by H2O, DCM, and hexane extracts, indicating predominant extraction of polar compounds. Phytochemical screening of the root extracts revealed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, terpenoids, and other secondary metabolites. TLC fingerprinting confirmed the presence of diverse vanillin-sulfuric acid reagent reactive compounds, while GC–MS. Analysis enabled the identification of phytoconstituents with known antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Water extract showed the strongest antioxidant activity, half maximal effective concentration (EC50) (EC₅₀ = 0.058 mg/ml), surpassing ascorbic acid and BHT, followed by methanol extract (EC₅₀ = 0.152 mg/ml). DCM and methanol extracts exhibited notable antibacterial activity against S. pyogenes (MICs of 0.078 and 0.312 mg/ml, respectively) but were largely inactive against the other tested strains.

Conclusion: This study represents the first report on the phytochemical profile and bioactivities of A. suaveolens roots. The findings demonstrate strong antioxidant potential and selective antibacterial activity that support the plant’s usage in traditional medicine and highlight its potential as a source of natural therapeutic agents. Further studies should focus on isolating bioactive constituents and elucidating their mechanisms of action.

Keywords: Asparagus suaveolens, Phytochemical screening, TLC-bioautography, GC–MS, Antioxidant activity, Antibacterial activity, South African medicinal plants

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i12.56584 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

South Africa is ranked among the top three countries globally in biodiversity, boasting an estimated 22,000–30,000 flowering plant species [1]. This rich biodiversity underpins the widespread use of medicinal plants in Southern Africa, where traditional remedies form a central component of primary healthcare [2–4]. For many rural communities, medicinal plants are the most accessible and affordable treatment options for common illnesses [5]. The pharmacological value of these plants is largely attributed to their secondary metabolites, which include phenolics, alkaloids, terpenoids, saponins, and flavonoids [6, 7]. These compounds have been associated with a wide range of biological activities, such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects [8, 9].

The genus Asparagus (family Asparagaceae) comprises approximately 120 to 300 species distributed globally, with East and Southern Africa recognised as major centres of diversification [10, 11]. Several species within this genus have been documented for their ethnomedicinal uses and pharmacological activities. For example, Asparagus racemosus is widely studied for its adaptogenic, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant properties [12], while Asparagus officinalis has demonstrated antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects [13]. These findings indicate that the genus is a valuable source of bioactive compounds with potential health benefits.

Amongst the genus Asparagus, Asparagus suaveolens is a perennial species indigenous to Southern Africa and is traditionally used by healers to treat urinary tract infections, including gonorrhoea, as well as epilepsy. In addition, it has applications in veterinary medicine for the treatment of livestock ailments [14]. Previous studies have investigated the aerial parts of A. suaveolens and reported the presence of glycosides, flavonoids, and terpenoids, alongside antioxidant and antibacterial properties [15–17]. However, to date, no scientific data exist on the phytochemical composition or biological activities of the roots of this species, despite anecdotal evidence of their use in traditional medicinal preparations.

Plants produce two main categories of metabolites. Primary metabolites are organic compounds that are essential for plant growth, development, and reproduction, such as carbohydrates, amino acids, and lipids. Secondary metabolites, on the other hand, are organic compounds that are not directly involved in primary metabolic processes but play crucial roles in ecological interactions, defence mechanisms, and adaptation. These include alkaloids, phenolics, tannins, saponins, and terpenoids, which have frequently been shown to exhibit potent pharmacological effects [7, 9].

In recent decades, there has been growing interest in the scientific validation of medicinal plants to identify novel therapeutic agents and natural product-based drug leads [18]. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities are of particular importance, given the global health burden posed by oxidative stress-related diseases and the rapid emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens [6, 19, 20]. Studies conducted on other Asparagus species suggest that this genus could be a valuable source of such bioactive compounds, yet the root extracts of A. suaveolens have never been investigated.

The aim of this study was therefore to characterise the phytochemical profile of A. suaveolens root extracts and to evaluate their antioxidant and antibacterial activities using qualitative and quantitative assays. This work represents the first report on the biological properties of A. suaveolens roots and contributes to the pharmacological validation of its traditional medicinal use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant extract preparation (collection and identification of the plant material)

To ensure authenticity of the plant material and compliance with biodiversity regulations, accurately identified roots of A. suaveolens were obtained for chemical and biological analyses. The roots were collected with the assistance of an Indigenous knowledge practitioner in Bolahlakgomo village (Zebediela) (24.451218° S; 29.326738° E), Lepelle-Nkumpi Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa, in accordance with environmental regulations. The identity of the plant species was authenticated by the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), Pretoria Herbarium, where the voucher specimen was deposited (PREART 0001903).

The roots were washed with deionised H2O, cut into smaller pieces, and dried at room temperature in the Department of Chemistry Laboratory using a Retsch Cutting Mill SM 100 (Germany) until completely dry. The dried material was ground multiple times into a fine powder. One kilogram of powdered material was subjected to cold maceration extraction by sequentially soaking in 3000 ml each of hexane, DCM, methanol, and H2O. Extractions were carried out using an OrbiShake Platform Shaker (Labotec, Model 261, 8 kg, 400 × 300, USA) at 117 rpm for 24 h at room temperature.

The resulting extracts were filtered through grade 3 Whatman filter paper (240 mm, Boeco, Germany) and concentrated using a Stuart rotary evaporator (RE 400, Cole-Parmer Ltd., Stone, Staffordshire, UK). Concentrated extracts were transferred into pre-weighed beakers and dried at room temperature under a stream of air.

Analysis of secondary metabolites within the root extracts of A. suaveolens

This analysis was conducted to identify the phytochemical classes that potentially contribute to the observed antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Various phytochemical analyses were conducted using standard methods with minor modifications, as reported and published by [21-23]. The analysis conducted in this study was to check for the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, tannins, and terpenoids.

Test for alkaloid

Aqueous hydrochloric acid was prepared by dissolving 0.1 ml of hydrochloric acid in 8 ml of distilled H2O, and distilled H2O was added until a 10 ml volume was reached. About 1 g of each extract was stirred with 5 ml of aqueous hydrochloric acid before being filtered. Then, 1 ml of filtrate was placed in two test tubes, six drops of Dragendorff’s reagent were added, and an orange-red precipitate indicated the presence of alkaloids.

Test for flavonoids

This was achieved by adding 10 ml of distilled H2O and 5 ml of dilute ammonia solution to 0.5 g of root extracts, followed by 1 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid. The presence of yellow colouration indicated the presence of flavonoids.

Test for glycosides

Ferric chloride was used, where 1 ml of glacial acetic acid and two drops of ferric chloride solution were added to 5 ml of each extract, followed by the addition of 1 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid. The presence of glycosides is indicated by a brown ring.

Test for saponins

To check for the presence of saponins, 5 ml of distilled H2O was added to 5 ml of root extract and shaken vigorously. A stable foam/froth was taken as a positive indication for the presence of saponins.

Test for steroids

To check for the presence of steroids, 1 ml of chloroform was added to 1 ml of plant extract. Thereafter, three drops of concentrated sulphuric acid were added to the mixture. The appearance of a brown ring was taken as an indication of the presence of steroids.

Ferric chloride tannins test

For this test, aliquots of 10 ml were boiled at 70 C in 5 ml deionised H2O before being filtered. Two drops of ferric chloride were added, and the formation of a blue-black colour was taken as an indication of the presence of tannins.

Terpenoids test

This test was carried out by adding 2 ml of chloroform and 3 ml of sulphuric acid to 200 mg of root extracts. The formation of a reddish-brown colouration was taken as a positive indication for the presence of terpenoids.

Phenol test

The ferric chloride test was used, where 2 ml of distilled H2O and four drops of ten percent ferric chloride were added to 1 ml of plant extract. Formation of a blueish-green colour in the test tube was taken as an indication of the presence of phenols in the plant extract.

Coumarin test

The sodium hydroxide test was followed, in which 1 ml of 10%sodium hydroxide was added to 1 ml of the extract. An immediate appearance of a yellow colour was taken as a positive indication of the presence of coumarins in the plant extract.

Quinone test

To check the presence of quinones, 1 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid was slowly added to 1 ml of the extract. Positive indication of the presence of quinones was observed by the appearance of a red colour.

Biological activity of plant extracts (Bioautographic antioxidant, DPPH, hydrogen peroxide scavenging and reducing power assay)

These assays were performed to assess the extracts’ antioxidant potential through multiple mechanisms, enabling correlation between phytochemical content and bioactivity. The TLC chromatographic technique was used to conduct the bioautography assay based on the method primarily reported by Masoko, as well as Siddeeg and their colleagues [24], with some modifications. Solvent systems with different polarities were prepared by mixing different solvents at different ratios, which included ethyl acetate, methanol, and H2O (EMW) (40/5.5/5, v/v/v); benzene, ethanol, and ammonia (BEA) (45/5/0.5, v/v/v); and finally, chloroform, ethyl acetate and formic acid (CEF) (25/2/5, v/v/v). Each of the prepared solvent systems was poured into the thin-layer chromatography tanks. Approximately 100µl of the extract (125 mg/ml) was spotted on TLC plates (Macherey-Nagel, Pre-coated TLC sheets ALUGRAM, silica gel 60 UV245, 20 cm x 20 cm, Germany) and placed in the tanks and closed to maintain optimal conditions. The plates were then allowed to develop until the solvent front had reached at least 80% of the plate before being taken out and allowed to dry. About 0.2%solution of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was prepared by dissolving 0.2g of DPPH in 100 ml of methanol. Vanillin-sulphuric solution was prepared by dissolving 0.1g of vanillin in 28 ml of methanol and 1 ml of sulphuric acid. Thereafter, the dried TLC plates were sprayed with a 0.2% solution of DPPH free radical and vanillin-sulphuric solution.

Evaluation of antioxidant activity

DPPH free radical scavenging assay

The DPPH assay was selected for its sensitivity and reproducibility in measuring the free radical scavenging ability of plant extracts, reflecting potential antioxidant efficacy in biological systems. The antioxidant activity of the extracts was evaluated through the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging assay as described by [25] with minor modifications. Briefly, a fresh methanolic solution of DPPH (0.8 mmol) was prepared, and 1 ml of various concentrations of extracts (2-10 mg/ml) was mixed with 1 ml of the DPPH solution. The mixture was vortexed and left to stand for 30 min, and then the absorbance was measured at 517 nm against the blank DPPH solution. Ascorbic acid and Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) were used as standards.

Ferric chloride reducing power assay

This assay was included to determine the electron-donating capacity of the extracts, which complements radical scavenging tests by targeting metal ion reduction pathways involved in oxidative stress. The reducing power ability of the plant extracts was evaluated using the protocol as described by [26, 29] with ascorbic acid and butylhydroxytoluene (BHT) as the standard. A stock solution of 1% potassium ferricyanide was prepared by dissolving 100 mg potassium ferricyanide in 8 ml of distilled water, and then distilled water was added to a total of10 ml. Sodium phosphate buffer was prepared by dissolving 0.93g Sodium dihydrogen phosphate and 1.73g Sodium hydrogen phosphate. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was prepared by dissolving 1g of TCA in 8 ml of distilled water. Distilled water was added until the volume reached 10 ml. In carrying out the assay, 1.0 ml of various concentrations of plant extracts (2-10 mg/ml) was mixed with 2.5 ml of potassium ferricyanide and 2.5 ml of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6). The mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 30 min, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 2.5 ml TCA, which was then followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Two millilitres of ferric chloride solution was added to distilled H2O until a volume of 10 ml was reached. The upper layer (2.5 ml) was mixed with 2.5 ml of deionised water and 0.5 ml of ferric chloride. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm against the blank, and the reducing power ability of the sample was determined by an increase in the absorbance of the sample.

Hydrogen peroxide scavenging assay

This test was performed to evaluate the extracts’ ability to neutralise hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species contributing to oxidative damage, thus providing a broader assessment of antioxidant potential. The ability of the plant extract to scavenge hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was determined using the protocol as prescribed by [27] with minor modifications. Aliquot of 1 ml of extracts (2-10 mg/ml) were transferred into Eppendorf tubes, 4 ml of 50 mmol phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was added, followed by the addition of 6 ml of H2O2solution. Hydrogen peroxide solution was prepared by dissolving 14µl of 30% hydrogen peroxide in 8 ml of distilled water. Distilled water was added to make a combined volume of 10 ml. The reaction mixture was vortexed, and after 10 min, the absorbance was measured at 230 nm against blank solutions containing plant extracts in phosphate buffer saline without H2O2. Ascorbic acid and BHT were used as the positive control.

Qualitative and quantitative antibacterial activity

These assays were designed to evaluate the extracts’ antibacterial spectrum and potency against clinically relevant Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, allowing the identification of specific targets.

Test organisms

For antibacterial analysis, the following strains purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (South Africa) were used in this study; Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC9721), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC25923), Escherichia coli(ATCC10536) and Streptococcus pyogenes(ATCC19615). These bacterial strains were chosen primarily based on their pathogenicity and subsequently used to evaluate the antimicrobial activities of the extracts. For the maintenance of the bacterial strains, glycerol stock cultures of each organism were prepared and stored at-80 °C until needed.

Antibacterial activity evaluation

Qualitative antibacterial activity assay

The TLC-bioautography approach was chosen to visualise antibacterial activity directly on chromatograms, enabling the linkage between observed bioactivity and specific chemical constituents. The qualitative antibacterial activity assay was performed with minor modifications to the method described by [28]. Briefly, 100 µl** of each extract was loaded onto a TLC plate and developed in a tank containing the benzene, ethyl acetate, and ammonia (BEA) solvent system. The plates were dried and subsequently sprayed with actively growing Streptococcus pyogenes cultures suspended in Mueller–Hinton Broth. They were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a shaking incubator, then sprayed with p-iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT) solution (2 mg/ml). Following a further 1-hour incubation at 37 °C, zones of bacterial growth inhibition were visualised.

MICs against pathogenic bacterial strains assay

The broth microdilution method was employed for its standardisation, reproducibility, and suitability in determining the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of plant extracts. A single colony of each bacterial strain was transferred into sterile Mueller–Hinton broth prepared by dissolving 10.5 g of Mueller–Hinton powder in 500 ml of distilled water. The broth cultures were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a shaking incubator. The bacterial suspension was then adjusted to an optical density (OD₆₀₀) of 0.1 using a microtiter plate reader, and this preparation step was repeated throughout the study to maintain consistency.

The broth dilution assay, as described by [29], was used to determine the MICs of the four plant extracts against the selected pathogens. Stock solutions (10 mg/ml) of each extract were prepared by dissolving 0.1 g in 1% aqueous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). From each stock, 100 µl** was transferred into an Eppendorf tube containing 900 µl** distilled H2O. Subsequently, 100 µl** of Mueller–Hinton broth was dispensed into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Triplicate wells in the first row received 100 µl** of the prepared extract solution, followed by two-fold serial dilutions from row A to H, resulting in final concentrations ranging from 2.5 mg/ml to 0.01 mg/ml; the last 100 µl** from row H was discarded.

Plates included ciprofloxacin (0.0001 mg/ml) as a positive control and 1% DMSO as a negative control. In wells containing standards, 100 µl** broth and 100 µl** of the respective bacterial suspension were added. Serial dilutions were prepared in the same manner, yielding the same concentration range. Once prepared, plates were sealed with adhesive film and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, 40 µl** of p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (INT, 0.20 mg/ml) was added to each well, followed by an additional 1 h incubation at 37 °C. Bacterial growth inhibition was visualised, and the MIC was recorded as the lowest concentration showing no visible growth. All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated to confirm reproducibility.

RESULTS

Extraction for qualitative and quantitative screening results

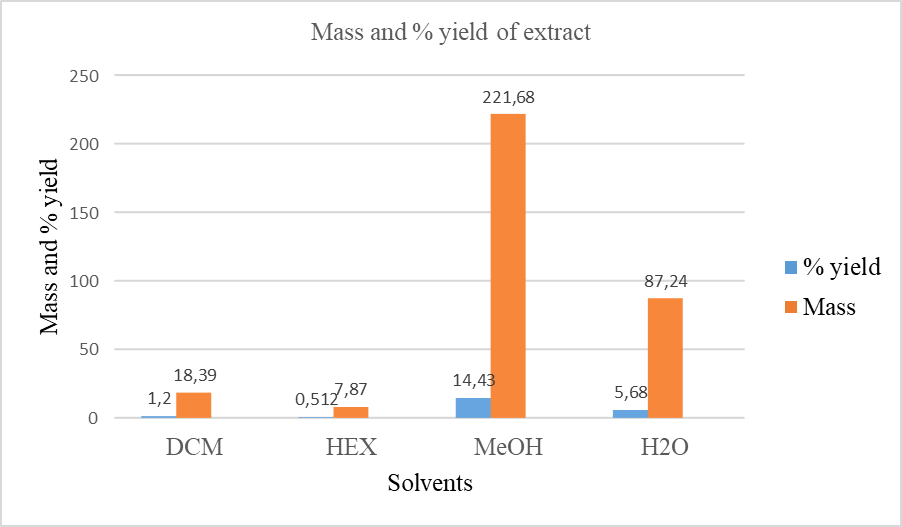

The ground roots of A. suaveolens were sequentially extracted using n-hexane, dichloromethane, methanol, and H2O, and the extraction masses and percentage yields are presented in fig. 1. The highest yield was obtained with methanol, followed by H2O, DCM, and n-hexane.

Qualitative phytochemical analysis results

Phytochemical screening tests results of the roots of A. suaveolens are presented in table 1 below, and they indicate that the plant possesses most of the common phytochemicals.

As shown in table 1, the hexane extract of A. suaveolens contained all the evaluated phytochemicals except coumarins. Alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, steroids, and tannins were weakly present, whereas terpenoids were strongly present. In the dichloromethane (DCM) extract, only glycosides (weak) and terpenoids (moderate) were detected; all other phytochemicals were absent.

The methanol extract contained alkaloids, coumarins, flavonoids, glycosides, steroids, and terpenoids at weak levels, while phenols and tannins were present at moderate levels. Saponins were absent from this extract. In the water extract, flavonoids, glycosides, and tannins were weakly present, phenols, saponins, and terpenoids were moderately present, and alkaloids, coumarins, and steroids were not detected.

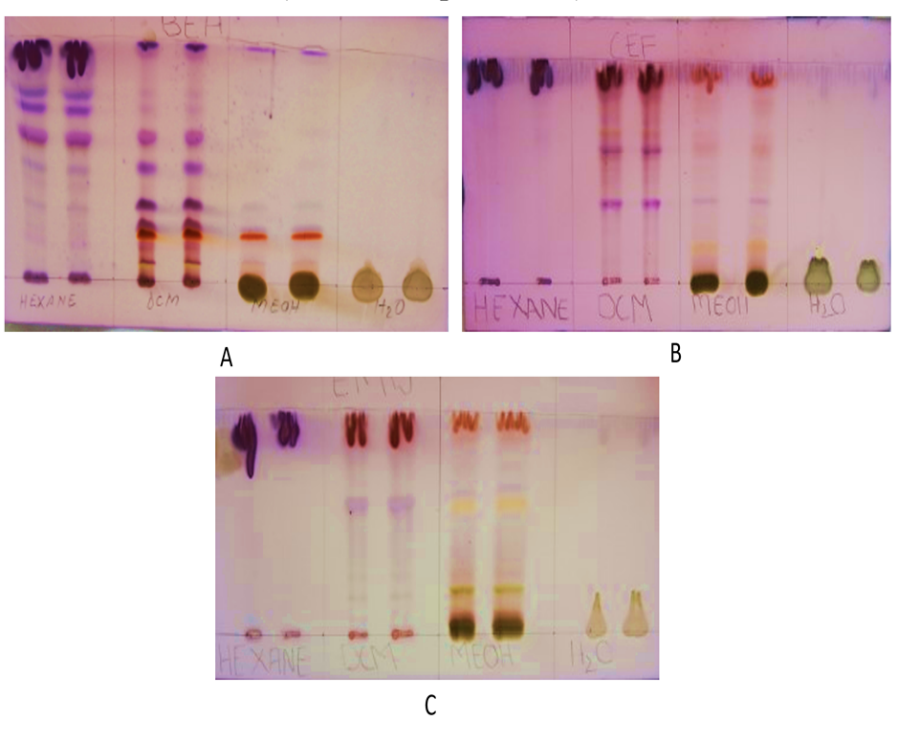

TLC fingerprinting of vanillin-sulfuric acid reagent reactive compounds

The plant extracts were subjected to TLC fingerprinting for vanillin-sulfuric acid reagent reactive compounds as a form of phytochemical composition characterisation, and the results are shown in fig. 2. The different colours seen on the chromatogram represent compound bands and provide evidence of the detection of the presence of different classes of compounds within the plant extracts.

Fig. 1: Extraction yields (%, w/w; Mass, mg) from the roots of Asparagus suaveolens using solvents of different polarities (HEX: n-hexane, DCM: dichloromethane, MeOH: methanol and H2O: water)

Table 1: Qualitative phytochemical screening of Asparagus suaveolens root extracts

| Phytochemical group | n-Hexane | Dichloromethane | Methanol | Water |

| Alkaloids | + | - | + | - |

| Coumarins | - | - | + | - |

| Flavonoids | + | - | + | + |

| Glycosides | + | + | + | + |

| Phenols | + | - | ++ | ++ |

| Resins | + | - | ++ | +++ |

| Saponins | + | - | - | ++ |

| Starch | + | - | ++ | +++ |

| Steroids | + | - | + | - |

| Tannins | + | - | ++ | + |

| Terpenoids | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

(-: Absence,+: weakly present,++: moderately present,+++: strongly present)

Fig. 2: TLC fingerprinting of vanillin-sulfuric acid reagent reactive compounds present in different plant extracts. TLC chromatograms were developed using different solvent systems (A: BEA, B: CEF and C: EMW), and different colours indicate different classes of compounds).

Thin-layer fingerprinting of the extract revealed 46 different bands across the 4 extracts when resolved using 3 different mobile systems. On the least polar extracts, the hexane extracts as per fig. 3 above and the table below, 9 bands were detected, implying at least 9 different compounds or classes of phytochemical compounds. The Rf values of the different bands range from 0.31 to 0.94. The dichloromethane extract, on the other hand, revealed the largest number of bands with 18 bands at Rf values that range from 0.08 to 0.97, across the 3 solvent systems. On the polar extracts, methanol has the greatest number of bands at 15, while the water extract only revealed 2 bands.

Table 2: Rf values of vanillin-sulphuric acid reagent reactive components within the root extracts of Asparagus suaveolens depicted from TLC chromatograms

| Components | BEA No. of spots | Rf values | CEF No. of spots | Rf values | EMW No. of spots | Rf values |

| Hexane | 6 | 0.31 0.45 0.57 0.69 0.76 0.92 |

2 | 0.940 0.941 |

1 | 0.910 |

| Dichloromethane | 9 | 0.080 0.120 0.093 0.200 0.240 0.310 0.470 0.600 0.970 |

6 | 0.360 0.590 0.670 0.740 0.830 0.930 |

3 | 0.160 0.560 0.920 |

| Methanol | 5 | 0.093 0.200 0.230 0.310 0.970 |

6 | 0.160 0.370 0.490 0.610 0.810 0.930 |

4 | 0.090 0.200 0.586 0.957 |

| Water | 1 | 0.043 | 1 | 0.058 |

As shown in fig. 3, the hexane extract of A. suaveolens produced six distinct spots when developed in BEA (benzene: ethanol: ammonia) with Rf values of 0.31, 0.45, 0.57, 0.69, 0.76, and 0.92. Using CEF (chloroform: ethyl acetate: formic acid), only two closely related spots were detected (Rf 0.940 and 0.941), while EMW (ethanol: methanol: water) yielded a single spot at Rf 0. 910. The dichloromethane (DCM) extract displayed the highest number of resolved spots across the three solvent systems. BEA development produced nine spots (Rf 0.080, 0.120, 0.093, 0.200, 0.240, 0.310, 0.470, 0.600, and 0.970), CEF produced six (Rf 0.360, 0.590, 0.670, 0.740, 0.830, and 0.930), and EMW yielded three (Rf 0.160, 0.560, and 0.920).

The methanol extract produced fewer spots than the other solvents. Under BEA, five spots were detected (Rf 0.093, 0.200, 0.230, 0.310, and 0.970); under CEF, six spots (Rf 0.160, 0.370, 0.490, 0.610, 0.810, and 0.930); and under EMW, four spots (Rf 0.090, 0.200, 0.586, and 0.957). The water extract yielded the fewest spots overall, with only one spot in CEF (Rf 0.043) and one in EMW (Rf 0.058). These TLC fingerprinting results demonstrate varying degrees of compound separation and solvent polarity preferences among extracts, reflecting the chemical complexity of A. suaveolens. The vanillin–sulphuric acid staining confirmed the presence of reactive compounds in all solvent extracts.

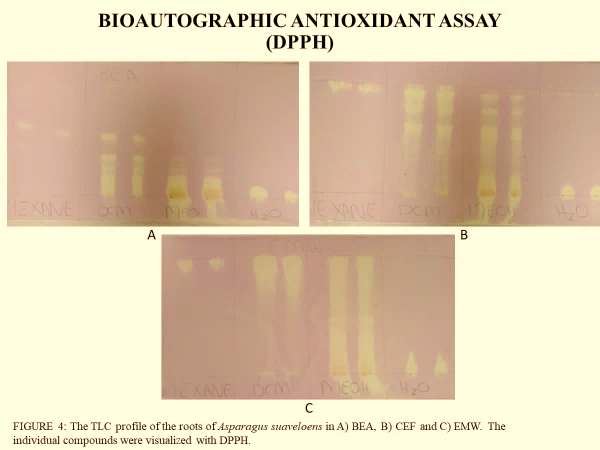

Fig. 3: The TLC fingerprinting of the compounds with free radical scavenging activity within the root extracts of Asparagus suaveolens. (The discolouration of the reddish-purplish DPPH to a yellowish colour denotes free radical scavenging activity for potential antioxidant properties).

Table 3: Rf values of DPPH-reactive components within the root extracts of Asparagus suaveolens depicted from TLC chromatograms

| Components | BEA No. of spots | Rf values | CEF No. of spots | Rf values | EMW No. of spots | Rf values |

| Hexane | 1 | 0.933 | 1 | 0.921 | 1 | 0.940 |

| Dichloromethane | 4 | 0.173 0.387 0.493 0.840 |

5 | 0.293 0.627 0.787 0.907 0.973 |

1 | 0.868 |

| Methanol | 1 | 0.122 | 4 | 0.640 0.693 0.813 0.907 |

3 | 0.088 0.191 0.912 |

| Water | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

(ND: no bands detected)

The assessment of antioxidant activity in different extracts, based on their DPPH reactivity, is presented in table 2. The results indicate distinct variations in the number and intensity of DPPH-reactive bands among the extracts. The hexane extract exhibited only three DPPH-reactive bands, with retention factor (Rf) values of 0.933, 0.921, and 0.940, suggesting the presence of a limited number of antioxidant compounds in this fraction.

In contrast, the dichloromethane extract displayed a significantly higher number of DPPH-reactive bands, with ten bands detected at Rf values ranging from 0.173 to 0.973. This indicates a broader diversity of antioxidant compounds in the dichloromethane fraction. Similarly, the methanol extract demonstrated eight DPPH-reactive bands, with Rf values spanning from 0.122 to 0.912, suggesting a relatively high antioxidant potential, though slightly lower than that of the dichloromethane extract.

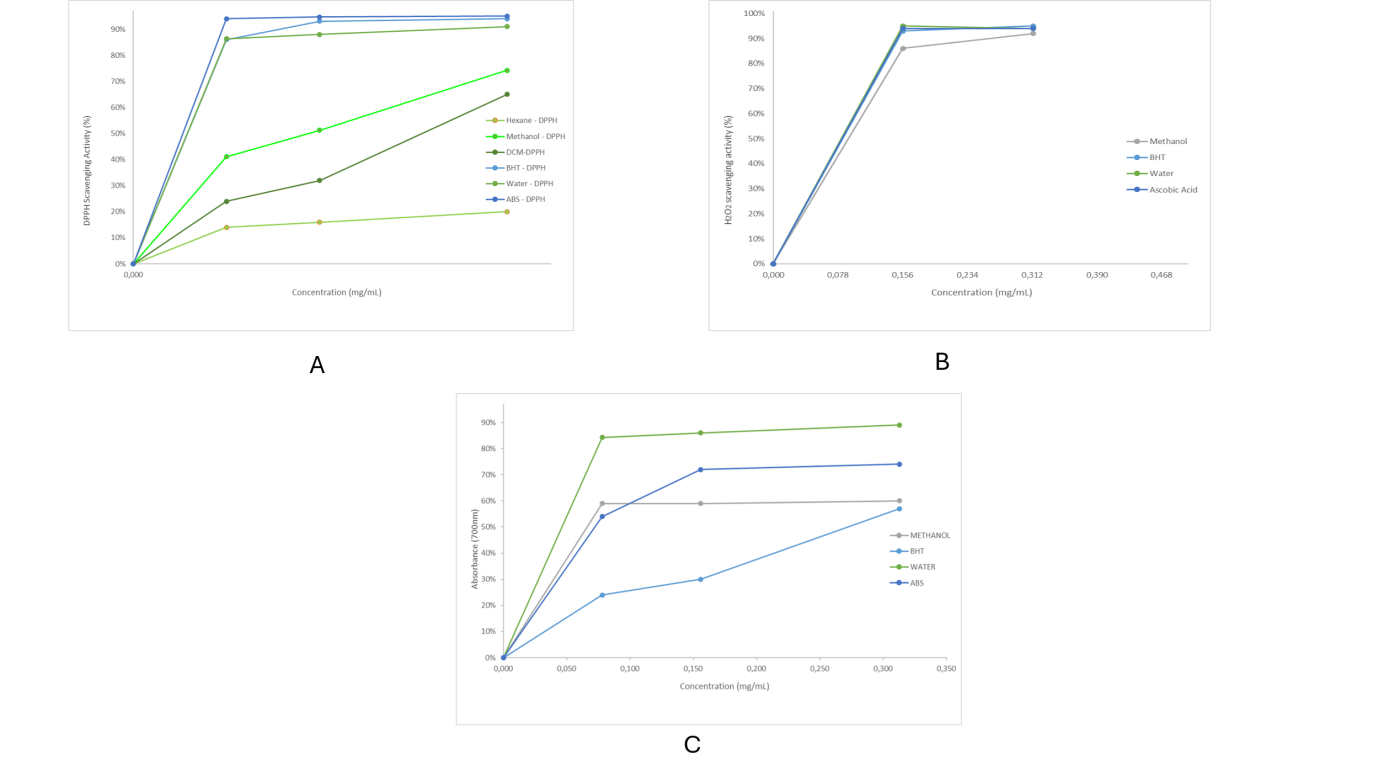

Quantitative evaluation of antioxidant activity

Quantitative evaluation for antioxidant activity through the DPPH, FRAP and H2O2 assay shown in fig. 4 (A, for DPPH inhibition; B, for H2O2 inhibition and C for reducing power ability of the extracts).

Fig. 4: Qualitative evaluation of antioxidant activity of root extracts of A. suaveolens. (A: DPPH inhibition activity; B: H2O2 inhibition activity; C: Reducing power ability of the roots of A. suaveolens, indicating the free radical scavenging ability of the extracts

Table 4: EC50 values (mg/ml) of Asparagus suaveolens in DPPH scavenging, hydrogen peroxide and reducing power assays

| Fractions/Standards | DPPH (EC50) | Hydrogen peroxide (EC50) | Reducing power (EC50) | Average (EC50) |

| Ascorbic acid | 0,410 | 0,084 | 0,071 | 0,188d |

| BHT | 0,045 | 0,084 | 0,272 | 0.134b |

| DCM | 0,245 | Nd | Nd | 0,245e |

| Hexane | >0.313 | Nd | Nd | >0.313f |

| Methanol | 0,147 | 0,090 | 0,220 | 0,152c |

| Water | 0,045 | 0,084 | 0,046 | 0,058a |

(Nd: no data, a: lowest EC50, b: second lowest EC50, c: third lowest EC50, d: third highest EC50, e: second highest EC50, f: highest EC50)

The half maximal effective concentration (EC50)

The EC50 values were determined from the inhibition plots in fig. 4 and the values shown in table 4. The root water extract of A. suaveolens had the lowest average EC50 amongst the extracts, which was also lower than those of the used standards, followed by the methanol extract, which was comparable with those of the standard reagents. The non-polar extracts, hexane and DCM, showed higher EC50 values.

Antibacterial activity, determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The results indicated higher recorded MIC values (above 1 mg/ml) by the extracts against most of the selected test organisms, except in the case of S. pyogenes, where the DCM and the MeOH extracts showed lower MIC values of 0.078 and 0.312 mg/ml, respectively. The growth inhibitory activity of the DCM and the MeOH extracts against S. pyogenes was confirmed through bioautography antibacterial activity analysis, as shown in fig. 6. Clear zones of growth inhibition were visible on the TLC chromatogram.

TLC bioautographic screening of the root extracts of A. suaveolens for antibacterial activity

The TLC bio-autography of the root extracts of A. suaveolens was conducted using four bacterial strains (two g-positive and two g-negative). The results indicate growth inhibition zones against Streptococcus pyogenes from the DCM and MeOH root extracts of A. suaveolens, as shown in fig. 5.

Fig. 5: TLC bioautography antibacterial activity analysis showing growth inhibition against Streptococcus pyogenes from the DCM and the MeOH root extracts of Asparagus suaveolens. (circled area shows clear zones on the chromatogram that depict growth inhibition of the bacterial strains by compound(s) within the extract)

DISCUSSION

The present study provides the first scientific report on the phytochemical composition, antioxidant potential, and antibacterial activity of Asparagus suaveolens root extracts. Extraction yields varied considerably among solvents, with methanol producing the highest yield, followed by water, dichloromethane, and hexane. This pattern indicates that the majority of extractable constituents in the roots are polar in nature, a finding consistent with previous reports on other medicinal plants where polar solvents have been shown to extract higher quantities of secondary metabolites [30-32]. The predominance of polar constituents in A. suaveolens roots suggests that traditional preparations using aqueous decoctions may be effective in extracting bioactive compounds.

Phytochemical screening revealed the presence of diverse classes of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, tannins, steroids, and terpenoids, many of which are associated with well-documented pharmacological activities. Alkaloids have been reported to exhibit antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [9, 33-35], while flavonoids and phenolics are recognised as potent antioxidants with anti-inflammatory potential [36-38]. The strong presence of terpenoids in the hexane extract and moderate to strong levels of phenolics in methanol and water extracts are in agreement with findings from previous studies on the phytochemical analysis of related Asparagus species, such as A. officinalis and A. racemosus, which were shown to possess a rich array of bioactive phytochemicals [12, 13].

TLC fingerprinting was used to profile the phytochemical composition of the plant extracts, particularly the detection compounds that are reactive to the vanillin-sulphuric acid reagent, and for the detection of compounds with antioxidant properties through the DPPH bioautography procedure. TLC phytochemical characterisation confirmed the chemical diversity of the extracts, with dichloromethane and methanol extracts displaying the highest number of resolved compound bands on the chromatograph, indicating the presence of multiple compounds of varying polarities. The vanillin-sulphuric acid reagent staining revealed distinct colour patterns, suggesting the presence of sugars, phenolics, terpenes, and steroids. TLC DPPH bioautography highlighted bands with free radical scavenging activity, evidenced through the discolouration of the DPPH free radical solution, particularly in the dichloromethane and methanol fractions. Interestingly, although the water extract exhibited no visibly resolved DPPH-reactive compound bands on TLC as the DPPH discolouration occurred only at the sample loading baseline on the TLC plate, quantitative assays demonstrated that it possessed the highest antioxidant capacity, with an EC₅₀ value (0.058 mg/ml) lower than those of ascorbic acid and BHT. This finding suggests that antioxidant compounds in the aqueous extract could be of higher polarity than the mobile phases used in the development of the TLC chromatograms and hence could not be moved through capillary action over the stationary phase to resolve constituent compounds.

The strong antioxidant activity of the water extract could be attributed to phenolic compounds detected, given that phenolic compounds are known to act as hydrogen donors and radical scavengers [39-41]. Methanol extracts also demonstrated notable antioxidant activity (EC₅₀ = 0.152 mg/ml), which can be linked to the combined presence of phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins. In contrast, hexane and dichloromethane extracts showed relatively weaker antioxidant activity, which may be explained by their lower phenolic content and the predominance of non-polar compounds such as terpenoids that typically contribute less to free radical scavenging properties [42].

Antibacterial assaying revealed that most of the evaluated A. suaveolens root extracts exhibited high MIC values (>1 mg/ml) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli, indicating lower activity strength. However, both dichloromethane and methanol extracts demonstrated profound inhibitory effects against Streptococcus pyogenes, with MIC values of 0.078 and 0.312 mg/ml, respectively. These MIC values fall within the range considered promising for crude plant extracts [29]. TLC-bioautography confirmed these findings by showing clear growth inhibition zones on chromatograms corresponding to specific compounds in these extracts. The selective antibacterial activity against S. pyogenes suggests that the active constituents are likely semi-polar and optimally extracted by intermediate polarity solvents such as dichloromethane and methanol.

The lack of broad-spectrum antibacterial activity may be due to the narrow antimicrobial spectrum of the active compounds present in A. suaveolens roots. This selectivity, however, can be advantageous for targeted applications, as it may limit disruption of beneficial microbiota and reduce the risk of resistance development compared to broad-spectrum agents. Comparable results have been reported for other medicinal plants where selective activity against Gram-positive bacteria was observed, often attributed to differences in cell wall structure and permeability between Gram-positive and Gram-negative species [19].

Overall, the findings from this study not only validate some aspects of the traditional use of A. suaveolens but also highlight its potential as a source of bioactive compounds with strong antioxidant and selective antibacterial properties. The novel demonstration of antibacterial activity against S. pyogenes is particularly significant, as this pathogen is associated with a range of human diseases, including pharyngitis, skin infections, and invasive conditions. Future work should focus on bioassay-guided fractionation to isolate and structurally characterise the active compounds, as well as on mechanistic studies to elucidate their modes of action. Additionally, assessing cytotoxicity and in vivo efficacy will be critical for determining the therapeutic potential of these root-derived extracts.

CONCLUSION

This study presents the first comprehensive evaluation of the phytochemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and antibacterial activity of Asparagus suaveolens root extracts. The results demonstrated that the roots are rich in diverse secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, steroids, and terpenoids, with polar solvents, particularly methanol and water, yielding the highest extract quantities. Quantitative assays revealed that the water extract exhibited exceptional antioxidant activity, surpassing that of standard synthetic and natural antioxidants, while methanol also showed notable activity. Antibacterial analysis indicated selective but significant activity of the dichloromethane and methanol extracts against Streptococcus pyogenes, findings that were further validated through TLC-bioautography.

These results not only provide scientific validation for certain traditional uses of A. suaveolens but also highlight its potential as a source of natural antioxidant agents and selective antibacterial compounds. The novelty of demonstrating root-derived activity against S. pyogenes offers a foundation for further pharmacological exploration. Future research should focus on isolating and characterising the bioactive constituents, investigating their mechanisms of action, and assessing their safety and efficacy in biological systems. By advancing our understanding of the medicinal potential of A. suaveolens, this work contributes to the broader effort of developing plant-based therapeutic agents from South Africa’s rich botanical resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Department of Biochemistry at Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences for their valuable contribution to this study, and the Department of Chemistry at Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University for allowing the study to be conducted in their lab.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

HNE Mashiloane designed and conducted the study, collected the data, performed formal analyses, and drafted the initial manuscript. MT Olivier and SS Gololo served as supervisors; they conceptualised the study, provided methodological guidance, and contributed to data analysis and critical revision of the manuscript. NS Mapfumari contributed to data analysis, coordinated and integrated manuscript sections, critically revised the text, and is the corresponding author responsible for submission and communication with the journal. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Street RA, Prinsloo G. Commercially important medicinal plants of South Africa: a review. J Chem. 2013;2013(1):205048. doi: 10.1155/2013/205048.

Vasisht K, Kumar V. Compendium of medicinal and aromatic plants of Africa. Trieste, Italy: ICS-UNIDO; 2004.

Van Wyk BE. A broad review of commercially important southern African medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119(3):342-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.05.029, PMID 18577439.

Shirinda H, Leonard C, Candy G, Van Vuuren S. Antimicrobial activity and toxicity profile of selected southern African medicinal plants against neglected gut pathogens. S Afr J Sci. 2019;115(11/12):1-10. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2019/6199.

Tilburt JC, Kaptchuk TJ. Herbal medicine research and global health: an ethical analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(8):594-9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.042820, PMID 18797616.

Salehi B, Martorell M, Arbiser JL, Sureda A, Martins N, Maurya PK. Antioxidants: positive or negative actors. Biomolecules. 2018;8(4):124. doi: 10.3390/biom8040124, PMID 30366441.

Pagare S, Bhatia M, Tripathi N, Pagare S, Bansal YK. Secondary metabolites of plants and their role: overview. Curr Trends Biotechnol Pharm. 2015;9(3):293-304. doi: 10.5958/2249‑0035.2015.00016.9.

Jain C, Khatana S, Vijayvergia R. Bioactivity of secondary metabolites of various plants: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2019;10(2):494-504. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.10(2).494-04.

Thawabteh A, Juma S, Bader M, Karaman D, Scrano L, Bufo SA. The biological activity of natural alkaloids against herbivores cancerous cells and pathogens. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11(11):656. doi: 10.3390/toxins11110656, PMID 31717922.

Norup MF, Petersen G, Burrows S, Bouchenak Khelladi Y, Leebens Mack J, Pires JC. Evolution of asparagus L. (Asparagaceae): out-of-South-Africa and multiple origins of sexual dimorphism. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;92:25-44. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.06.002, PMID 26079131.

Boubetra K, Amirouche N, Amirouche R. Comparative morphological and cytogenetic study of five Asparagus (Asparagaceae) species from Algeria, including the endemic A. altissimus Munby. Turk J Bot. 2017;41(6):588-99. doi: 10.3906/bot-1612-63.

Shevale UL, Mundrawale AS, Yadav SR, Chavan JJ, Jamdade CB, Patil DB. Phytochemical and antimicrobial studies on asparagus racemosus. World J Pharm Res. 2015;4(9):1805-10.

Begum A, Sindhu K, Giri K, Umera F, Gauthami G, Kumar JV. Pharmacognostical and physico-chemical evaluation of Indian Asparagus officinalis Linn family Lamiaceae. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2017;9(3):327-36. doi: 10.25258/phyto.v9i2.8083.

Dold AP, Cocks ML. Traditional veterinary medicine in the Alice district of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa: research in action. S Afr J Sci. 2001;97(9):375-9.

Jayawickreme KP, Janaka KV, Subasinghe SA. Unknowing ingestion of Brugmansia suaveolens leaves presenting with signs of anticholinergic toxicity: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):322. doi: 10.1186/s13256-019-2250-1, PMID 31665073.

Daemane ME, Cilliers SS, Bezuidenhout H. Classification and description of the vegetation in the Spitskop area in the proposed Highveld National Park, North West Province, South Africa. Koedoe. 2012;54(1):1-7. doi: 10.4102/koedoe.v54i1.1020.

Sobhy Y, Mady M, Mina S, Abo Zeid Y. Phytochemical and pharmacological values of two major constituents of asparagus species and their nano formulations: a review. J Adv Pharm Res. 2022;6(3):94-106. doi: 10.21608/aprh.2022.141715.1176.

Jain C, Khatana S, Vijayvergia R. Bioactivity of secondary metabolites of various plants: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2019;10(2):494-504. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.10(2).494-04.

Kowalska Krochmal B, Dudek Wicher R. The minimum inhibitory concentration of antibiotics: methods, interpretation clinical relevance. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):165. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020165, PMID 33557078.

Gomes EC, Silva AN, De Oliveira MR. Oxidants, antioxidants and the beneficial roles of exercise-induced production of reactive species. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:756132. doi: 10.1155/2012/756132, PMID 22701757.

Abdu M, Saad MG, Shafik HM. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activities of some green algae from Egypt. J Med Plants Stud. 2019;7(3):12-6.

Mukul DS, Kumar DA, Mokhtar DE, Pandey DS, Singh DS. Diagnostic dilemma in temporomandibular joint tuberculosis: a case report. IJMSCI. 2017;4(4):2856-58. doi: 10.18535/ijmsci/v4i4.09.

Usman H, Abdulrahman FI, Usman A. Qualitative phytochemical screening and in vitro antimicrobial effects of methanol stem bark extract of Ficus thonningii (Moraceae). Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(3):289-95. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v6i3.57178, PMID 20448855.

Siddeeg A, Al Kehayez NM, Abu Hiamed HA, Al Sanea EA, Al Farga AM. Mode of action and determination of antioxidant activity in the dietary sources: an overview. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(3):1633-44. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.064, PMID 33732049.

Abu F, Mat Taib CN, Mohd Moklas MA, Mohd Akhir S. Antioxidant properties of crude extract, partition extract and fermented medium of dendrobium sabin flower. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:2907219. doi: 10.1155/2017/2907219, PMID 28761496.

Vasyliev GS, Vorobyova VI, Linyucheva OV. Evaluation of reducing ability and antioxidant activity of fruit pomace extracts by spectrophotometric and electrochemical methods. J Anal Methods Chem. 2020;2020:8869436. doi: 10.1155/2020/8869436, PMID 33489417.

Pleh A, Mahmutovic L, Hromic Jahjefendic A. Evaluation of phytochemical antioxidant levels by hydrogen peroxide scavenging assay. Bioeng Stud. 2021;2(1):1-10. doi: 10.37868/bes.v2i1.id178.

Suleiman MM, Mc Gaw LI, Naidoo V, Eloff JN. Detection of antimicrobial compounds by bioautography of different extracts of leaves of selected South African tree species. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7(1):64-78. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i1.57221.

Itumeleng TB, Idowu JA, Abdullahi AY, Sekelwa C. Antibacterial antiquorum sensing antibiofilm activities and chemical profiling of selected South African medicinal plants against multi-drug resistant bacteria. J Med Plants Res. 2022;16(2):52-65. doi: 10.5897/JMPR2021.7192.

Hostettmann K, Wolfender JL. The search for biologically active secondary metabolites. Pestic Sci. 1997;51(4):471-82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9063(199712)51:4<471::AID-PS662>3.0.CO;2-S.

Schugerl K. Extraction of primary and secondary metabolites. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2005;92:1-48. doi: 10.1007/b98920, PMID 15791931.

Jones WP, Kinghorn AD. Extraction of plant secondary metabolites. In: Cannell RJ, editor. Natural products isolation. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006. p. 323-51.

Matsuura HN, Fett Neto AG. Plant alkaloids: main features, toxicity and mechanisms of action. In: Gopalakrishnakone P, editor. Plant toxins. Berlin: Springer; 2015. p. 1-15. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6728-7_2-1.

Ziegler J, Facchini PJ. Alkaloid biosynthesis: metabolism and trafficking. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:735-69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092730, PMID 18251710.

Dusemund B, Nowak N, Sommerfeld C, Lindtner O, Schafer B, Lampen A. Risk assessment of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in food of plant and animal origin. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;115:63-72. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.03.005, PMID 29524571.

Falcone Ferreyra ML, Rius SP, Casati P. Flavonoids: biosynthesis, biological functions and biotechnological applications. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:222. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00222, PMID 23060891.

Grotewold E. The science of flavonoids. New York: Springer; 2006.

Hodek P. Flavonoids. In: Anzenbacher P, Zanger UM, editors. Metabolism of drugs and other xenobiotics. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Press; 2012. p. 543-82. doi: 10.1002/9783527630905.ch20.

Irshad M, Zafaryab MD, Singh M, Rizvi MM. Comparative analysis of the antioxidant activity of Cassia fistula extracts. Int J Med Chem. 2012;2012:157125. doi: 10.1155/2012/157125, PMID 25374682.

Pereira DM, Valentao P, Pereira JA, Andrade PB. Phenolics: from chemistry to biology. Molecules. 2009;14(6):2202-11. doi: 10.3390/molecules14062202.

Ozcan T, Akpinar Bayizit A, Yilmaz Ersan L, Delikanli B. Phenolics in human health. Int J Chem Eng Appl. 2014;5(5):393-6. doi: 10.7763/IJCEA.2014.V5.416.

Noda Y, Asada C, Sasaki C, Nakamura Y. Effects of hydrothermal methods such as steam explosion and microwave irradiation on extraction of water-soluble antioxidant materials from garlic husk. Waste Biomass Valor. 2019;10(11):3397-402. doi: 10.1007/s12649-018-0353-3.