Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 12, 49-56Original Article

COMPARATIVE EFFICACY OF SACUBITRIL/VALSARTAN VERSUS ACE INHIBITORS OR ARBS IN ACHIEVING TARGET BLOOD PRESSURE AMONG ADULTS WITH HYPERTENSION: A META-ANALYSIS OF RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS

PRANAB DAS

Department of Pharmacology, Pragjyotishpur Medical College and Hospital, Guwahati, Assam, India

*Corresponding author: Pranab Das; *Email: pranabdas2580123@gmail.com

Received: 21 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 07 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the comparative efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in achieving blood pressure (BP) control (<140/90 mmHg) among adults with hypertension.

Methods: A meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing sacubitril/valsartan with ACEIs or ARBs in adult hypertensive patients and reporting the proportion of individuals achieving target BP were included. Four eligible RCTs were identified through systematic searches of PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool, and the certainty of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach. A random-effects model was employed to pool risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: The pooled analysis demonstrated that sacubitril/valsartan was significantly more effective than ACEIs or ARBs in achieving BP control, with a pooled RR of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.14–1.35). Heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 58.2%), and leave-one-out sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results. No significant publication bias was detected through Egger’s regression or funnel plot inspection. The overall certainty of the evidence was rated as moderate.

Conclusion: Sacubitril/valsartan improves the likelihood of achieving target blood pressure levels compared to ACEIs or ARBs in adults with hypertension. These findings support the potential of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) as a more effective therapeutic option in contemporary hypertension management.

Keywords: Sacubitril, Valsartan, ARNI, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, Hypertension, Blood pressure control, Meta-analysis, Randomized controlled trials

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i12.56600 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension remains one of the most prevalent chronic conditions worldwide, affecting an estimated 1.28 billion adults and contributing to significant morbidity and mortality through its strong association with cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal diseases (World Health Organization, 2021) [1]. Despite the availability of effective pharmacological therapies, global blood pressure (BP) control rates remain suboptimal, with fewer than 50% of treated individuals achieving the recommended target of<140/90 mmHg [2]. Poor control is often related to therapeutic resistance, suboptimal adherence, or limitations of existing drug classes [3].

The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) plays a central role in hypertension pathophysiology. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) remain foundational therapies due to their proven efficacy and organ-protective benefits [4]. However, limitations exist, as many patients fail to achieve sustained BP control despite RAAS blockade, highlighting the need for alternative or adjunctive mechanisms [5]. Conventional monotherapy is often inadequate in resistant or high-risk hypertensive populations, necessitating exploration of novel pharmacological strategies [6].

Sacubitril/valsartan, a first-in-class angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), offers a unique dual mechanism: neprilysin inhibition increases levels of natriuretic peptides, bradykinin, and adrenomedullin, leading to vasodilation, natriuresis, and reduced sympathetic drive, while concurrent angiotensin receptor blockade attenuates RAAS-mediated vasoconstriction and sodium retention [7, 8]. This dual action provides synergistic antihypertensive effects beyond conventional RAAS blockade. Several studies have demonstrated that sacubitril/valsartan lowers systolic and diastolic BP more effectively than ACEIs or ARBs alone, with additional benefits on vascular remodelling and left ventricular hypertrophy regression [9, 10].

Emerging evidence suggests potential advantages of sacubitril/valsartan in resistant hypertension and in patients with comorbid conditions such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease [11, 12]. Preclinical and clinical studies highlight its favourable hemodynamic profile, safety, and tolerability compared to established antihypertensive drugs, though cost and long-term data remain considerations [13, 14]. Almost each fifth adult individual coming in contact with the health system was found hypertensive, reinforcing the need for early detection and timely intervention [15]. Some research paper reinforce that sacubitril/valsartan demonstrates superior BP-lowering efficacy and broader cardiovascular protective effects compared with standard antihypertensives, supporting the rationale for further comparative evaluation [16].

Given the high global burden of uncontrolled hypertension and the limitations of conventional therapies, there is a compelling need to synthesize randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence directly comparing sacubitril/valsartan with ACEIs or ARBs in terms of BP control rates. Such comparative evidence may provide clinicians with stronger guidance on therapeutic sequencing, particularly for resistant hypertensive populations or those with comorbidities. This meta-analysis aims to address this evidence gap by pooling RCT data to quantify the relative efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan versus ACEI/ARB therapy in achieving target BP. Clinically, the findings may support potential revisions in hypertension management strategies and inform guideline recommendations for broader ARNI use. The objective of this research is to quantitatively evaluate whether sacubitril/valsartan improves the likelihood of achieving controlled BP (<140/90 mmHg) compared with ACE inhibitors or ARBs among adults with hypertension.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research question

This meta-analysis addressed the clinical question: Among adult patients with hypertension, does sacubitril/valsartan (ARNI) therapy result in a higher proportion of individuals achieving target blood pressure (BP) control (<140/90 mmHg) compared to treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)?

Study design and reporting standards

The meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines to ensure transparent reporting and methodological rigor [17]. The review protocol was developed prior to study commencement. Risk of bias in included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2) tool [18]. The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach was used to assess the certainty of evidence, when applicable [19].

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis, studies were required to be randomized controlled trials (RCTs) enrolling adult participants aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with hypertension. Eligible populations included individuals with essential hypertension, resistant hypertension, or hypertension coexisting with heart failure. The intervention under investigation had to involve sacubitril/valsartan (ARNI), administered in any clinically approved dosage or formulation. The comparison group must have received either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), as monotherapy or within standard antihypertensive regimens. Studies were required to report a binary outcome measure, specifically, the proportion of patients achieving target blood pressure control defined as<140/90 mmHg during the study follow-up. Only full-text, peer-reviewed articles published in English between January 1, 2018, and August 1, 2025, were considered. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the predefined methodological criteria. Trials employing non-randomized or observational study designs, such as cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies, were not eligible. Studies involving paediatric populations or those that failed to report the primary binary outcome of blood pressure control were also excluded. Additionally, duplicate reports, interim analyses of already included trials, and articles published in languages other than English or not subjected to peer review were excluded from the analysis.

Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic literature search was conducted across four electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search encompassed studies published from the January 1, 2018 of each database up to August 1, 2025. The search strategy was designed to capture all relevant randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan compared to ACE inhibitors or ARBs in achieving blood pressure control in patients with hypertension.

To enhance the sensitivity and specificity of the search, a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords was utilized. The search terms included variations and synonyms of the key concepts: "sacubitril/valsartan", "angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor", "ARNI", "angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor", "ACE inhibitor", "angiotensin receptor blocker", "ARB", "hypertension", and "blood pressure control". These terms were strategically combined using Boolean operators, such as “AND” to ensure the intersection of concepts, “OR” to include synonyms or related terms, and “NOT” to exclude irrelevant records.

For example, a simplified structure of the PubMed search string was as follows: ("sacubitril/valsartan" OR "ARNI" OR "angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor") AND ("ACE inhibitors" OR "angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor" OR "enalapril" OR "lisinopril" OR "ramipril") OR ("ARBs" OR "angiotensin receptor blocker" OR "olmesartan" OR "valsartan" OR "telmisartan") AND ("hypertension" OR "high blood pressure" OR "blood pressure control") AND ("randomized controlled trial" OR "RCT" OR "randomised controlled trial")

To ensure comprehensive coverage, no filters were initially applied to study design or language during the search phase. After retrieval, filters were applied manually during screening to include only randomized controlled trials, published in English, and meeting the defined time frame.

In addition to database searching, the reference lists of all included articles and relevant systematic reviews were manually examined to identify any additional eligible studies not captured in the initial search.

Study selection process

The process of selecting studies was conducted in alignment with the PRISMA 2020 framework, encompassing four key stages: identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion [17]. In the identification phase, records were retrieved through comprehensive searches across multiple electronic databases. Titles and abstracts were then screened to determine their relevance during the subsequent stage. Full-text articles were thoroughly reviewed to assess whether they met the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that satisfied all eligibility requirements were included in the final meta-analysis. Duplicate entries were removed systematically, and justifications for exclusion were documented at each step. Ultimately, four studies were deemed eligible and included, each providing binary outcome data suitable for quantitative synthesis. Title and abstract screening was independently performed by two reviewers, with any disagreements resolved through consensus or, when necessary, arbitration by a third reviewer.

Data extraction process

Two reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized data collection form in Microsoft Excel 365. Extracted variables included study characteristics (study ID, author, year, sample size, follow-up duration), participant demographics, intervention details (ARNI type and dose), comparator details, and binary outcome data (BP control<140/90 mmHg). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or referral to a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the risk ratio (RR) for achieving blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg), comparing sacubitril/valsartan with ACE inhibitors or ARBs. A random-effects model was used for meta-analysis, applying the DerSimonian and Laird method to account for between-study heterogeneity [20]. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for pooled effect sizes. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using the I² statistic, with I²>50% considered substantial [21]. Assessment of publication bias using funnel plots and Egger’s test was conducted [22].

All analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel 365. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the robustness of the pooled estimate. Subgroup analysis was not performed due to the small number of included studies.

RESULTS

Study selection and sample characteristics

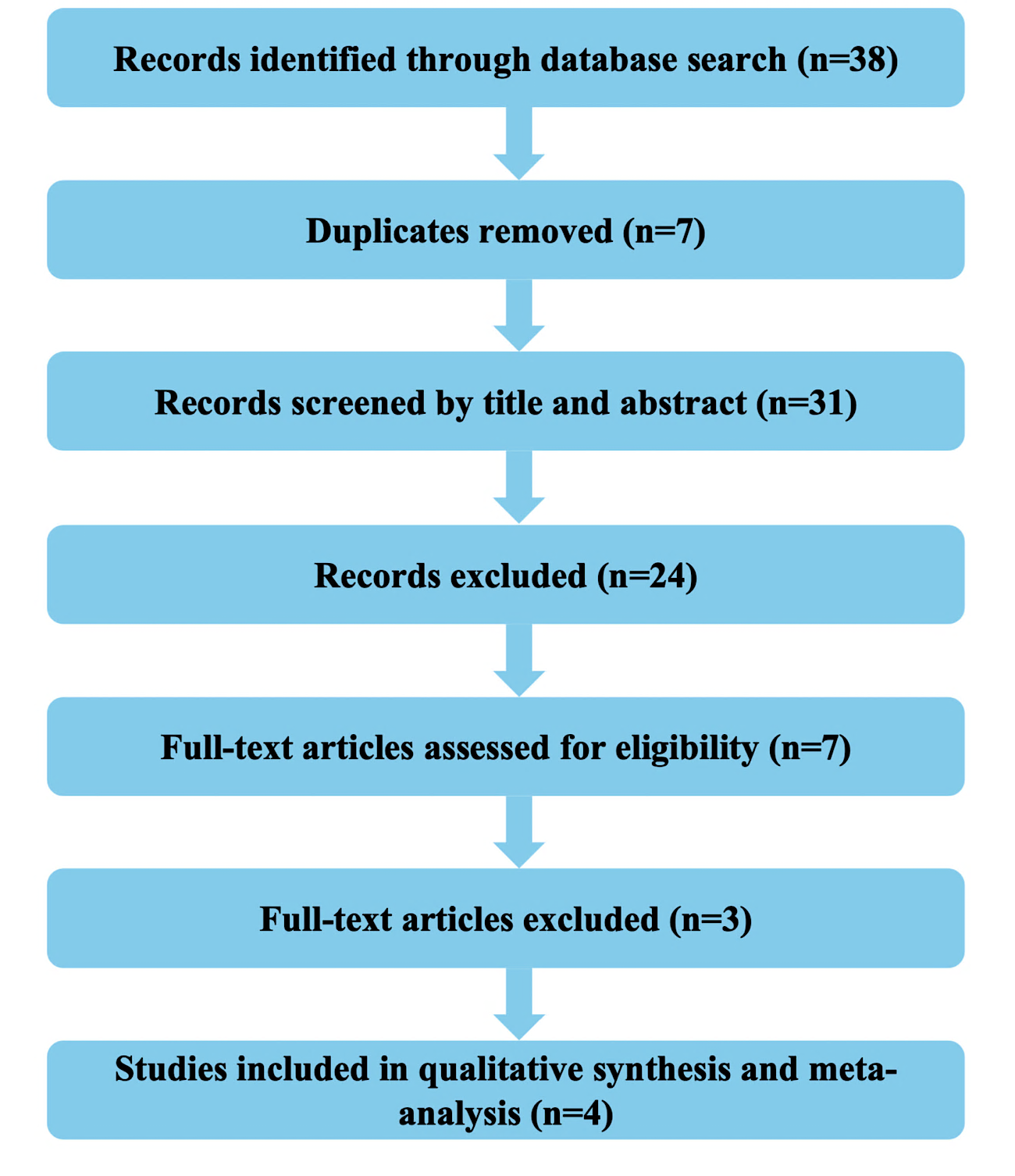

A total of 38 records were retrieved through systematic searches of electronic databases. Following the removal of 7 duplicate entries, 31 unique records were subjected to title and abstract screening. Of these, 24 studies were excluded for not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria based on their titles and abstracts. The remaining 7 articles were reviewed in full text for eligibility. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3 full-text articles were excluded due to insufficient outcome data or non-randomized design. Consequently, 4 randomized controlled trials metal eligibility requirements and were included in both the qualitative synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. The full study selection process is illustrated in table 1 and fig. 1, structured according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [18].

Table 1: PRISMA summary table

| Stage | Frequency (n) |

| Records identified through database searching | 38 |

| Duplicates removed | 7 |

| Records screened | 31 |

| Records excluded | 24 |

| Full-text articles assessed for eligibility | 7 |

| Full-text articles excluded | 3 |

| Studies included in qualitative and quantitative synthesis | 4 |

Fig. 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Study characteristics

Details of study attributes which were included in this research are displayed in table 2.

Meta-analysis findings

The effect estimates derived from the various included studies in the meta-analysis are summarised below in table 3.

Table 2: Characteristics of included randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

| Study ID | First author (Year) | Study design | Population | Intervention (Arni) | Comparator (ACEI or ARB) | Intervention dose | Comparator dose | Primary outcome | Proportion of patients achieving target outcome in intervention group* | Proportion of patients achieving target outcome in comparator group* | Duration (weeks) |

| S1 | Huo et al. (2019) | RCT, double-blind | Asian adults with mild–moderate hypertension | Sacubitril/valsartan | Olmesartan | 200 mg OD | 20 mg OD | BP control<140/90 mmHg | 256/477 | 235/481 | 8 |

| S2 | Jackson et al. (2021) | RCT post hoc analysis | Adults with HFpEF and resistant hypertension | Sacubitril/valsartan | Background ARB (Valsartan) | 97/103 mg BID | 160 mg BID (both arms) | BP control<140/90 mmHg | 163/340 | 127/370 | 16 |

| S3 | Rakugi et al. (2022) | RCT, Phase III, double-blind | Japanese adults with mild-moderate hypertension | Sacubitril/valsartan | Olmesartan | 200 mg OD | 20 mg OD | BP control<140/90 mmHg | 170/387 | 128/389 | 8 |

| S4 | Cheung et al. (2018) | RCT, Phase III, multi-center | Adults with essential hypertension | Sacubitril/valsartan | Olmesartan | 200 mg OD | 20 mg OD | BP control<140/90 mmHg | 76/188 | 52/187 | 8 |

*Proportion of patients achieving target outcome in intervention group = Sample size of intervention group showing the desired outcome/Total sample size of intervention group. **Proportion of patients achieving target outcome in Comparator group = Sample size of comparator group showing the desired outcome/Total sample size of comparator group.

Table 3: Summary of effect estimates for included studies in the meta-analysis

| Study ID | RR (Risk Ratio) | Log(RR) | SE (Standard Error) | Lower 95% confidence interval (Individual study) | Upper 95% confidence interval (Individual study) | Weight | Weighted Log (RR) | Pooled RR | SE of pooled Log(RR) | Lower 95% confidence interval (Meta-analysis) | Upper 95% confidence interval (Meta-analysis) |

| S1 | 1.09849681 | 0.09394271 | 0.06313581 | 0.97063626 | 1.24320025 | 250.869828 | 23.5673914 | 1.24 | 0.04329272 | 1.1386821 | 1.34929064 |

| S2 | 1.39671144 | 0.3341205 | 0.09146095 | 1.16749104 | 1.67093604 | 119.544213 | 39.9421724 | ||||

| S3 | 1.3349887 | 0.28892282 | 0.09241309 | 1.11381734 | 1.60007817 | 117.093557 | 33.8310012 | ||||

| S4 | 1.45376432 | 0.37415628 | 0.14738359 | 1.08902679 | 1.94065997 | 46.0364431 | 17.2248241 |

RR: Risk Ratio; SE: Standard Error; CI: Confidence Interval.

Interpretation of table 3

A total of four randomized controlled trials (S1 to S4) were included in the quantitative synthesis assessing the proportion of patients achieving target blood pressure (BP) (<140/90 mmHg) with sacubitril/valsartan compared to ACE inhibitors or ARBs. The meta-analysis yielded a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.24 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.14 to 1.35, indicating a statistically significant improvement in blood pressure control in the sacubitril/valsartan group relative to the comparator group. Individual study estimates showed RRs ranging from 1.10 (S1) to 1.45 (S4). All studies demonstrated point estimates favouring sacubitril/valsartan, with confidence intervals that did not cross the null value (RR = 1), suggesting consistent findings across trials. Study S4 exhibited the largest effect size (RR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.94), while study S1 had the smallest (RR = 1.10; 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.24), though still trending in the same direction. The weights assigned to each study in the random-effects model were proportional to the inverse variance, with study S1 contributing the greatest weight (approximately 251), reflecting its lower standard error and greater precision.

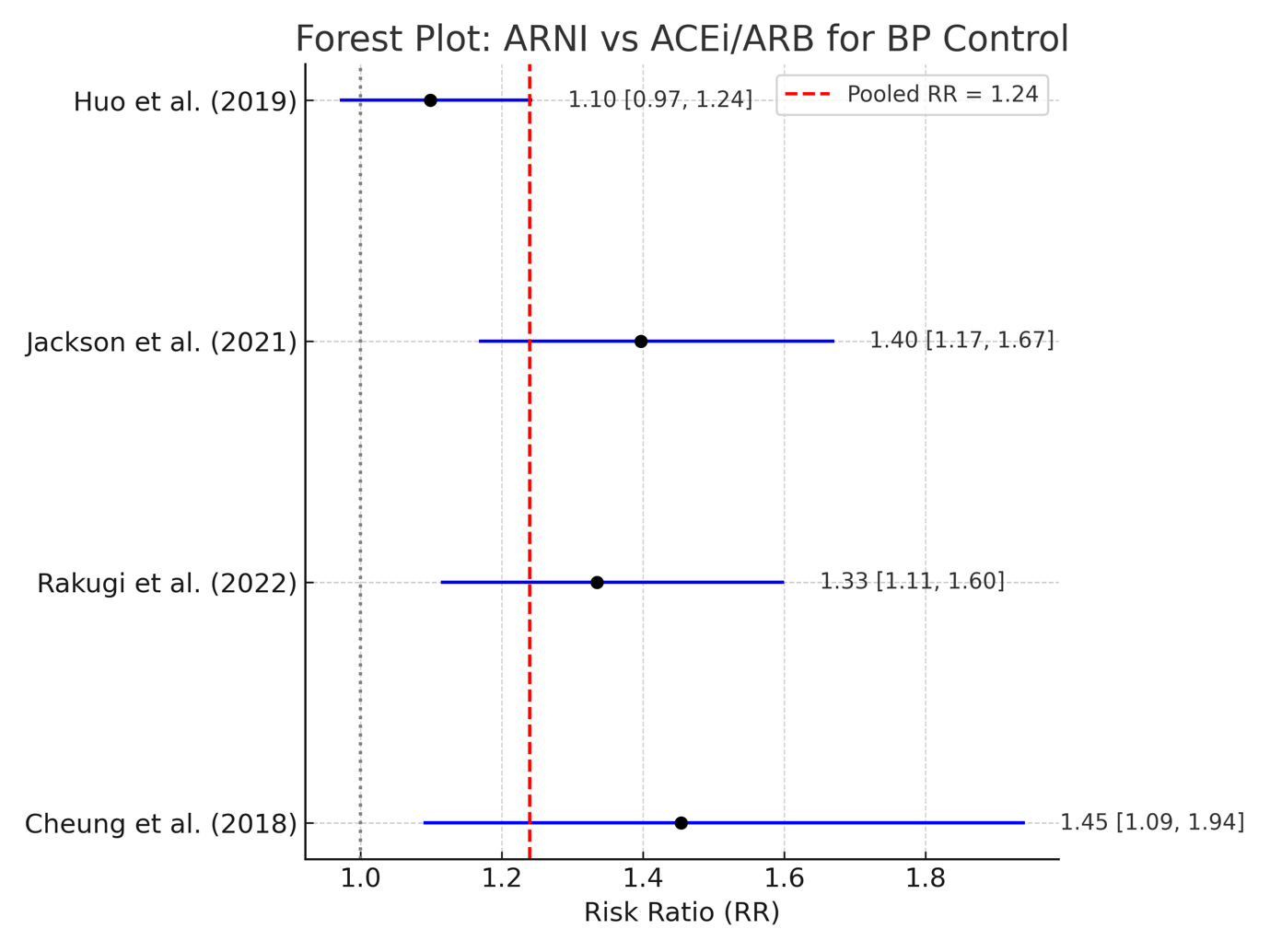

Forest plot

Fig. 2 presents the forest plot illustrating the risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each included randomized controlled trial, as well as the overall pooled estimate derived from the random-effects model.

Fig. 2: Forest plot comparing ARNI versus ACEI/ARB in achieving BP targets (<140/90 mm of Hg) among adults suffering from hypertension (RR = Risk Ratio)

Interpretation of forest plot (fig. 2)

It displays the individual and pooled risk ratios (RRs) for the included randomized controlled trials comparing sacubitril/valsartan to ACE inhibitors or ARBs in achieving target blood pressure control. Each study is represented by a black square (point estimate) and a horizontal line (95% confidence interval), while the vertical dashed red line indicates the overall pooled effect estimate from the random-effects model. Among the included studies, three trials, namely Jackson et al. (2021), Rakugi et al. (2022), and Cheung et al. (2018) demonstrated statistically significant improvements in blood pressure control with sacubitril/valsartan, as their confidence intervals did not cross the line of no effect (RR = 1). Specifically, the highest effect was observed in Cheung et al. (2018) (RR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.09–1.94), followed closely by Jackson et al. (2021) (RR = 1.40; 95% CI: 1.17–1.67) and Rakugi et al. (2022) (RR = 1.33; 95% CI: 1.11–1.60). Although Huo et al. (2019) reported a risk ratio favouring sacubitril/valsartan (RR = 1.10), the 95% confidence interval (0.97–1.24) included the null value, suggesting the result was not statistically significant. The pooled risk ratio was 1.24, indicating a 24% higher likelihood of achieving blood pressure control in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan compared to those receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs. This overall effect was statistically significant, as the 95% confidence interval ranged from 1.14 to 1.35, entirely above 1.0. These findings support the superior efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan over traditional RAAS inhibitors in promoting blood pressure control among adult hypertensive populations.

Publication bias assessment

Table 4 shows Egger’s regression test assessing small-study effects among trials included in the meta-analysis of ARNI versus ACEI/ARB for target BP achievement. The slope (β₁) and intercept (β₀) were derived using precision as the independent variable and standardized effect size as the dependent variable.

Table 4: Egger’s regression test for publication bias assessment

| Study ID | Log(RR) | SE (Standard error) | Inverse SE (Precision) | Standardized effect size | β₁ (Slope) | β₀ (Intercept) | SE of β₀ (Intercept) | t-value | df | p-value |

| S1 | 0.09394271 | 0.06313581 | 15.8388708 | 1.48794644 | -0.1293083 | 4.13617177 | 1.75269412 | 2.35989367 | 2 | 0.14223096 |

| S2 | 0.3341205 | 0.09146095 | 10.9336276 | 3.65314915 | ||||||

| S3 | 0.28892282 | 0.09241309 | 10.8209776 | 3.12642742 | ||||||

| S4 | 0.37415628 | 0.14738359 | 6.78501607 | 2.53865634 |

Interpretation of Egger’s regression test (table 4)

Egger’s regression test was performed to statistically evaluate the presence of small-study effects, which may indicate publication bias. The regression analysis was based on the association between the standardized effect sizes and the inverse of their standard errors (a measure of study precision). In this analysis, the intercept (β₀) was estimated at 4.14 with a standard error of 1.75, yielding a t-value of 2.36 and degrees of freedom (df) = 2. The corresponding p-value was 0.14 (p-value is>0.05), indicating that the result did not reach statistical significance. As a result, there is no strong evidence of publication bias among the included studies, since the intercept deviates from zero non-significantly. Although the intercept is slightly elevated, the wide confidence interval and non-significant p-value suggest that asymmetry in the funnel plot (if present) may be due to chance rather than systematic bias. These findings support the reliability of the pooled effect estimate and indicate that the observed treatment effect is unlikely to be substantially influenced by selective reporting or small-study effects.

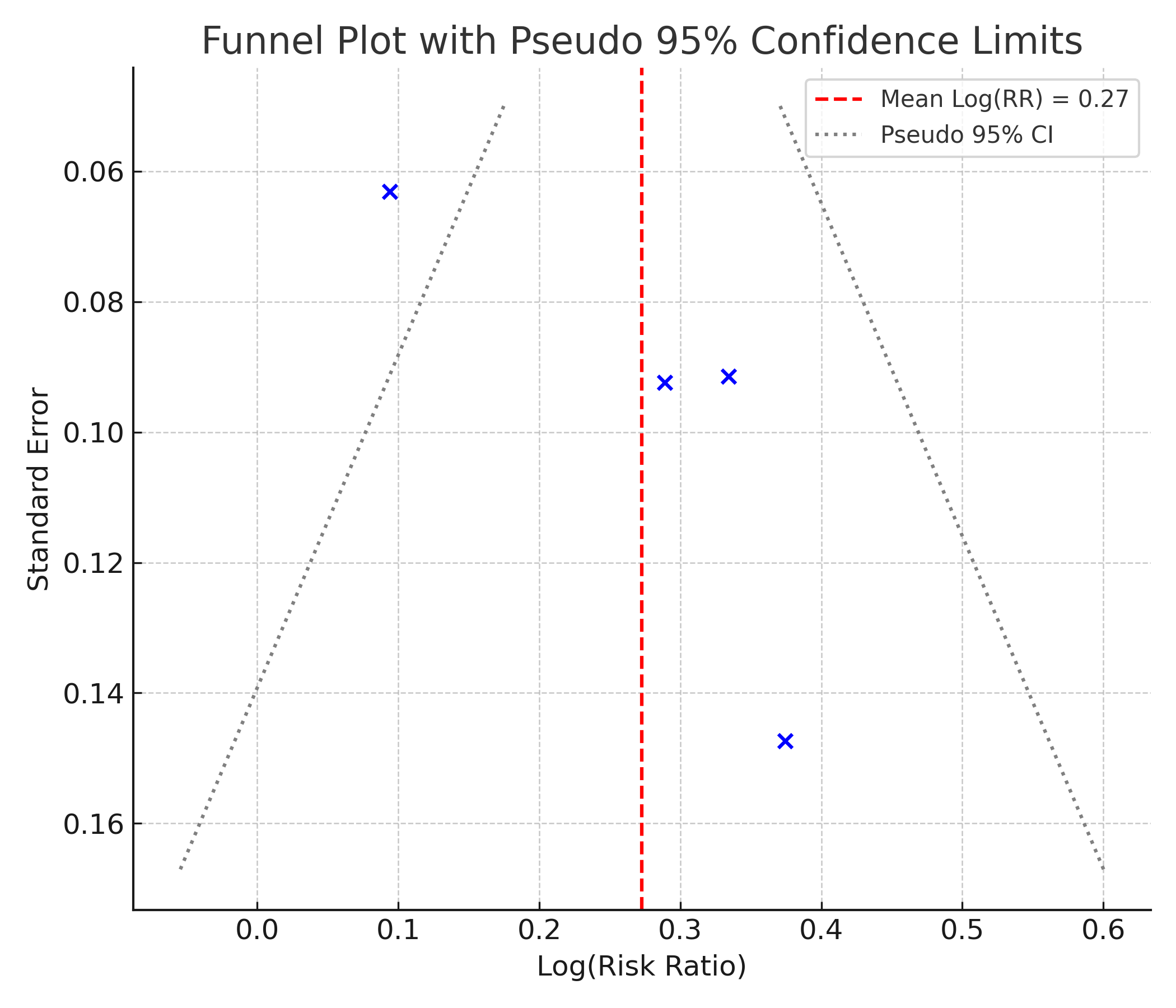

Fig. 3 shows the funnel plot assessment of the meta-analysis.

Fig. 3: Funnel plot assessing publication bias among the included studies comparing ARNI versus ACEI/ARB for BP target attainment. The vertical red dashed line represents the pooled log(RR), and the blue dashed lines indicate pseudo 95% confidence limits.

Interpretation of funnel plot (fig. 3)

The funnel plot displays a roughly symmetrical distribution of studies around the pooled Log (RR) estimate (indicated by the red dashed line). The data points do not appear to cluster asymmetrically to one side, and there is no clear pattern of small studies (with larger SE) showing extreme effect sizes. This visual impression supports the result of Egger’s test, suggesting no significant publication bias. The absence of asymmetry implies that smaller studies are not selectively missing from either side of the plot, which is an indicator of balanced evidence within the included trials.

Risk of bias assessment

Table 5 shows the Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment of the meta-analysis.

Table 5: Domain-based risk of bias assessment for the included randomized controlled trials

| Study ID | Domain 1 Judgment | Domain 2 Judgment | Domain 3 Judgment | Domain 4 Judgment | Domain 5 Judgment | Overall RoB | Justification |

| S1 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Well-randomized double-blind RCT; minimal missing data; BP measured objectively; outcomes prespecified. |

| S2 | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Post hoc subgroup analysis from PARAGON-HF; original trial well-designed, but risk of selective reporting and subgroup bias. |

| S3 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Industry-sponsored phase III double-blind trial with prespecified outcomes and robust randomization; low attrition. |

| S4 | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Small sample, pilot design; unclear randomization sequence details; otherwise robust blinding and outcome assessment. |

Interpretation of RoB assessment (table 5)

The risk of bias for the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was evaluated across multiple domains using a domain-based approach. Among the four studies assessed, two (S1 and S3) demonstrated consistently low risk of bias across all evaluated domains. Study S1 was a well-conducted, double-blind, randomized controlled trial with minimal missing data and objective measurement of blood pressure, and it followed a prespecified analysis plan. Similarly, Study S3, an industry-sponsored phase III double-blind trial, exhibited strong methodological rigor with adequate randomization, prespecified outcomes, and low levels of attrition. In contrast, Studies S2 and S4 were rated as having some concerns in specific domains. Study S2, a post hoc subgroup analysis derived from the PARAGON-HF trial, raised potential concerns regarding selective reporting and the validity of subgroup-specific conclusions, despite the overall high quality of the parent trial. Study S4, which employed a pilot design with a relatively small sample size, had an unclear randomization process. However, it maintained appropriate blinding and outcome measurement protocols, which helped to mitigate some bias concerns. Overall, while the majority of the included studies were rated as low risk, two studies exhibited moderate methodological limitations that warrant cautious interpretation of their findings.

Heterogeneity assessment

Table 6 presents the results of heterogeneity analysis using Cochrane’s Q and the I² statistic within the meta-analysis.

Interpretation of heterogeneity assessment (table 6)

Statistical heterogeneity across the included studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q statistic and the I² statistic. The Q value was 7.18 with 3 degrees of freedom, corresponding to the number of studies minus one. While the Q statistic suggests the presence of variability beyond chance, its significance is limited in small meta-analyses due to low power. The I² statistic was 58.2%, indicating moderate to substantial heterogeneity among the included trials. According to conventional thresholds, I² values between 50% and 75% suggest that more than half of the total variability in effect estimates may be attributed to true differences across studies rather than random error. This level of heterogeneity justifies the use of a random-effects model for meta-analysis and suggests that some clinical or methodological variability may be influencing the observed outcomes. Potential sources of heterogeneity may include differences in study populations, intervention protocols, or trial designs.

Table 6: Heterogeneity assessment of included randomized controlled trials

| Study ID | ((Log RR-pooled log RR)^2)*weight | Cochran's Q statistic | Degrees of freedom (df) | I2 statistic |

| S1 | 3.659796243 | 7.17872346 | 3 | 58.2098403 |

| S2 | 1.704129189 | |||

| S3 | 0.644632437 | |||

| S4 | 1.170165592 |

Table 7: Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis of included studies

| Removed study ID | Pooled Log(RR) | Q statistic | I² value (%) |

| S1 | 0.32191828 | 6.59005527 | 69.6512409 |

| S2 | 0.18024939 | 4.98251971 | 59.8596671 |

| S3 | 0.19386311 | 6.35283945 | 68.5180144 |

| S4 | 0.19966984 | 5.89805649 | 66.0905248 |

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed to assess how the exclusion of each individual study affected the overall pooled estimate and the degree of heterogeneity, as shown in table 7.

Interpretation of Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (table 7)

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the robustness of the pooled effect size and heterogeneity by sequentially removing each individual study from the meta-analysis. The analysis revealed that the overall pooled log risk ratio (Log[RR]) remained relatively stable, ranging from 0.18 to 0.32, indicating that no single study disproportionately influenced the overall effect estimate. In terms of heterogeneity, the Cochran’s Q statistic varied modestly between 4.98 and 6.59, while the I² statistic fluctuated between 59.9% and 69.7%, suggesting moderate to substantial heterogeneity persisted even after the exclusion of individual studies. The highest I² value was observed when S1 was removed, while the lowest was recorded upon the exclusion of S2. However, no substantial reduction in heterogeneity occurred with the removal of any single study, indicating that heterogeneity is likely driven by cumulative differences across multiple trials rather than an outlier effect from any one study.

GRADE assessment

The certainty of evidence derived from the meta-analysis was evaluated using the GRADE approach, as summarized in table 8.

Table 8: Evaluation of the certainty of evidence regarding BP reduction associated with ARNIvs. ACEI/ARB therapy, based on GRADE criteria

| Outcome | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall certainty level | Justification |

| BP control <140/90 mmHg | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Moderate | Two studies show some RoB concerns (S2, S4); moderate heterogeneity (I² ≈ 58%) without serious indirectness or imprecision; no evidence of small-study/publication bias. |

Interpretation of GRADE assessment (table 8)

The certainty of evidence for the outcome of achieving blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg) was evaluated using the GRADE framework. The overall certainty was rated as moderate. This rating was influenced by two key factors. First, risk of bias was identified in two of the included studies (S2 and S4), where methodological limitations, such as post hoc analyses and small sample sizes, raised some concerns. Second, inconsistency was noted due to moderate heterogeneity (I² ≈ 58%), suggesting variability in treatment effects across studies. However, the certainty of evidence was not downgraded for indirectness, as the study populations, interventions, and outcomes were directly relevant to the research question. Imprecision was also not a concern, given the narrow confidence intervals surrounding the pooled effect estimate. Furthermore, no evidence of publication bias was observed, supported by symmetrical funnel plot patterns and non-significant results from Egger’s test. Taken together, these considerations justify a moderate level of confidence in the pooled findings, indicating that the true effect is likely close to the estimated effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis synthesizes evidence from four randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of sacubitril valsartan with that of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in achieving target blood pressure control in adult patients with hypertension. The pooled risk ratio of 1.24, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 1.14 to 1.35, suggests a statistically and clinically significant advantage of ARNI therapy in improving the likelihood of achieving systolic and diastolic targets under 140/90 mmHg.

The observed superiority of ARNI is mechanistically plausible. Sacubitril/valsartan offers dual pharmacological activity by combining neprilysin inhibition with blockade of the angiotensin II receptor. This unique mechanism augments endogenous natriuretic peptide activity while simultaneously suppressing the vasoconstrictive effects of angiotensin II. Together, these effects promote vasodilation, natriuresis, and inhibition of sympathetic activity, all of which contribute to better hemodynamic regulation and blood pressure control [8].

Notably, our findings align with earlier analysis that have suggested ARNI may provide more consistent antihypertensive effects across various patient subgroups, particularly those with high cardiovascular risk. In a prospective open-label study conducted by Mazza et al., sacubitril valsartan was found to demonstrate favourable efficacy in reducing blood pressure (both systolic and diastolic) compared to control (comprising of ACEI or ARB or beta-blocker or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist), in patients with mild to moderate hypertension [23]. While that analysis primarily focused on surrogate endpoints such as systolic and diastolic reductions in mmHg, our study extends those findings by focusing on a binary clinical outcome, that is, achievement of target BP thresholds, which is more directly linked to guideline-based treatment goals.

Further supporting evidence comes from the PARAGON-HF subgroup analysis by Jackson et al., which specifically evaluated sacubitril valsartan in the context of resistant hypertension among patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). In that post hoc analysis, ARNI therapy was associated with a statistically significant improvement in blood pressure control, particularly among individuals previously unresponsive to conventional RAAS blockade [24]. The findings of our meta-analysis are consistent with this subgroup, reinforcing the value of ARNI not only in standard hypertension management but also in complex comorbid populations.

The heterogeneity across included trials was moderate (I² = 58.2 percent), which is expected given the variability in study populations, follow-up durations, and comparator regimens. Importantly, leave-one-out sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of the pooled effect, indicating that no single study disproportionately influenced the summary estimate. This robustness adds confidence to the overall conclusion.

The risk of bias assessment revealed that two studies (S1 and S3) demonstrated low risk across all domains, while the other two (S2 and S4) had some concerns, primarily related to subgroup analysis and unclear randomization procedures. However, these limitations did not substantially affect the overall findings, as supported by the GRADE assessment, which rated the certainty of evidence as moderate.

Publication bias was also unlikely to have influenced the results. Both Egger’s regression test and the symmetrical funnel plot suggested the absence of small study effects. This strengthens the credibility of the pooled estimate and supports the validity of the evidence synthesis.

This meta-analysis has several strengths that contribute to the reliability and relevance of its findings. First, it focused exclusively on randomized controlled trials, the highest standard of clinical evidence, which minimizes the potential for confounding and selection bias. Second, the analysis applied rigorous methodological standards, including adherence to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, use of the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool for risk of bias assessment, and the GRADE framework for evaluating certainty of evidence. Third, the primary outcome, which was the achievement of target blood pressure, was clinically meaningful, providing a patient-centred endpoint rather than relying solely on numerical reductions in systolic or diastolic values. Finally, sensitivity and publication bias assessments were conducted to confirm the robustness and reliability of the pooled results.

Despite its strengths, the meta-analysis is not without limitations. The most prominent limitation is the small number of included studies. Only four randomized controlled trials met the inclusion criteria, primarily because few trials reported the proportion of patients achieving target blood pressure. Most existing trials presented continuous blood pressure outcomes, such as reductions in systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure, without converting these data into binary outcomes. As a result, potentially eligible studies were excluded, which may limit the comprehensiveness of the analysis. Additionally, moderate heterogeneity was observed, which could reflect variations in trial design, population characteristics, or intervention protocols. The relatively short follow-up durations in the included trials may also restrict the generalizability of findings to long-term outcomes.

Future research should aim to standardize the reporting of hypertension outcomes, including both absolute blood pressure reductions and the proportion of patients reaching predefined treatment goals. Large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials with diverse populations and longer follow-up durations are needed to strengthen the evidence base. Moreover, head-to-head comparisons between sacubitril/valsartan and different classes of antihypertensives should be encouraged to identify patient subgroups that benefit the most from angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor therapy. Clinically, the findings of this meta-analysis suggest that sacubitril/valsartan may offer superior efficacy in helping patients achieve guideline-recommended blood pressure targets, potentially leading to better cardiovascular outcomes if applied more broadly in routine practice.

CONCLUSION

This meta-analysis demonstrated that sacubitril/valsartan (ARNI) therapy is significantly more effective than ACE inhibitors or ARBs in achieving blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg) among adult patients with hypertension. The pooled evidence, drawn from randomized controlled trials, supports a 24% higher likelihood of attaining target blood pressure levels with ARNI treatment. The findings remained consistent across sensitivity analysis and were not influenced by publication bias or single-study effects. Despite moderate heterogeneity and minor methodological concerns in two included studies, the overall certainty of evidence was graded as moderate. These results underscore the clinical potential of ARNI as a superior antihypertensive agent and provide a compelling rationale for its consideration in treatment guidelines for hypertension, particularly in patients who may benefit from more robust blood pressure control.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author sincerely acknowledges the valuable contributions of the original researchers whose studies were included in this meta-analysis. Appreciation and gratitude is also extended to the reviewers for their thoughtful critiques and insightful feedback, which significantly enhanced the quality and clarity of the final manuscript.

FUNDING

No external funding was received for the design, execution, analysis, or publication of this research.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Pranab Das was solely responsible for the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the manuscript. The author affirms full accountabilities for all aspects of the work and ensures its accuracy and integrity. This manuscript complies with the authorship criteria defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Hypertension. In: Geneva: WHO; 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension.

Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(4):223-37. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2, PMID 32024986.

Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and control of hypertension: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(11):1278-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.008, PMID 30190007.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb CD. A guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2017;71(6):e13-5. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065, PMID 29133356.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339, PMID 30165516.

Burnier M, Egan BM. Adherence in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1124-40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313220, PMID 30920917.

McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR. Angiotensin neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993-1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077, PMID 25176015.

Kario K, Williams B. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors for hypertension hemodynamic effects and relevance to hypertensive heart disease. Hypertens Res. 2022 Jul;45(7):1097-110. doi: 10.1038/s41440-022-00923-2, PMID 35501475.

Kario K, Sun N, Chiang FT, Supasyndh O, Baek SH, Inubushi Molessa A. Efficacy and safety of LCZ696 a first-in-class ARNI, in Asian patients with hypertension: a randomized double-blind study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43(9):1012-21. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0482-9, PMID 24446062.

Kolte D. Transcatheter edge-to-edge tricuspid valve repair for functional tricuspid regurgitation: does aetiology matter. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(9):1126-8. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1588, PMID 31407846.

Xie B, Gao Q, Wang Y, Du J, He Y. Effect of sacubitril valsartan on left ventricular remodeling and NT-proBNP in patients with heart failure complicated with hypertension and reduced ejection fraction. Am J Transl Res. 2024 May 15;16(5):1935-44. doi: 10.62347/KHQW5375, PMID 38883372.

Gu J, Noe A, Chandra P, Al Fayoumi S, Ligueros Saylan M, Sarangapani R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of LCZ696, a novel dual-acting angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi). J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(4):401-14. doi: 10.1177/0091270009343932, PMID 19934029.

Mishra S, Patel CJ, Patel MM. Development and validation of stability indicating chromatographic method for simultaneous estimation of sacubitril and valsartan in pharmaceutical dosage form. Int J App Pharm. 2017;9(5):1-8. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2017v9i5.19139.

Modi JK, Yadav M. Efficacy and safety of angiotensin receptor blockers in stage 1 hypertension: a hospital-based observational study. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2025;18(7):236-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2025.v18i7.54944.

Pandey D, Guleri SK, Sinha U, Pandey S, Tiwari S. Paradigmatic age shift of hypertension disease: a study among young adults. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(4):44-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i4.47564.

Pandey D, Guleri SK, Sinha U, Pandey S, Tiwari S. Paradigmatic age shift of hypertension disease: a study among young adults. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(4):44-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i4.47564.

Sharma S, Kumar Singh SK, Baranwal PK, Singh DK, Kale V. A cross-sectional study to estimate the prevalence of hypertension in urban field practice area of medical college in metropolitan city of India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(9):98-101. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i9.45926.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71, PMID 33782057.

Sterne JA, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019 Aug 28;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898, PMID 31462531.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso Coello P. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD, PMID 18436948.

Der Simonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2, PMID 3802833.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557, PMID 12958120.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629, PMID 9310563.

Mazza A, Townsend DM, Torin G, Schiavon L, Camerotto A, Rigatelli G. The role of sacubitril/valsartan in the treatment of chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in hypertensive patients with comorbidities: from clinical trials to real-world settings. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020 Oct 1;130:110596. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110596, PMID 34321170.

Gao J, Zhang X, Xu M, Deng S, Chen X. The efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan compared with ACEI/ARB in the treatment of heart failure following acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Aug 4;14:1237210. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1237210, PMID 37601056.

Jackson AM, Jhund PS, Anand IS, Dungen HD, Lam CS, Lefkowitz MP. Sacubitril valsartan as a treatment for apparent resistant hypertension in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 21;42(36):3741-52. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab499, PMID 34392331.