Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 12, 22-26Original Article

KNOWLEDGE, PRACTICE AND USABILITY OF TIBETAN HERBAL MEDICINE (SOWA RIGPA): A COMMUNITY BASED SURVEY IN THE SAJONG-KAGYUD AREA, SIKKIM, INDIA

GAYMIT LEPCHA, TIEWLASUBON URIAH KHAR, SONAM BHUTIA*

Department of Pharmacognosy, Government Pharmacy College Sajong, Government of Sikkim (GoS), Sikkim University, Rumtek, Sajong, Gangtok, Sikkim-737135, India

*Corresponding author: Sonam Bhutia; *Email: sonamkzbhutia@gmail.com

Received: 22 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 14 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The objective of present survey was to acquire the Knowledge, Practice, and Usability of Tibetan Herbal Medicine (Sowa Rigpa): A community survey in the Sajong-Kagyud area, Sikkim, India.

Methods: A study was conducted with n=17 out of 322 people from the area. Data were collected using a pre-designed questionnaire, face-to-face interview about demographics, reasons for using Tibetan medicine, and details about its uses.

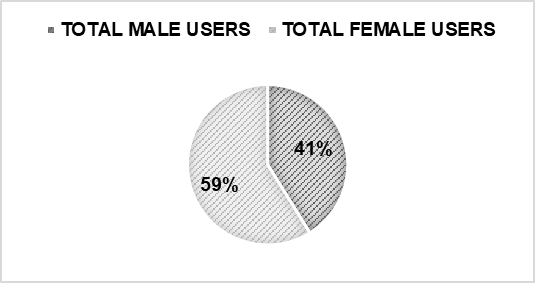

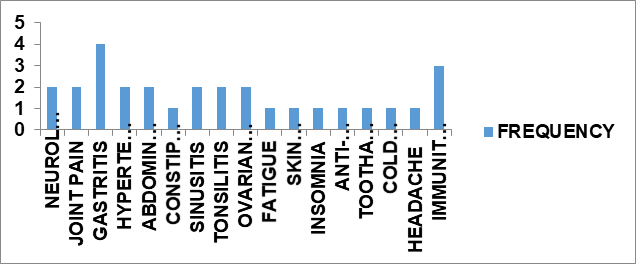

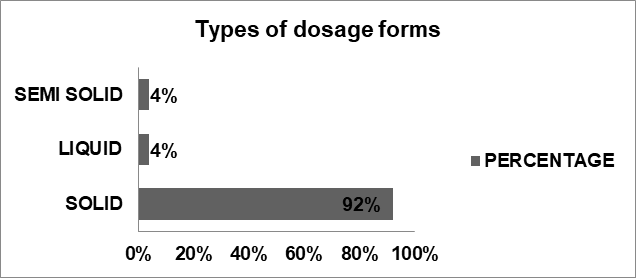

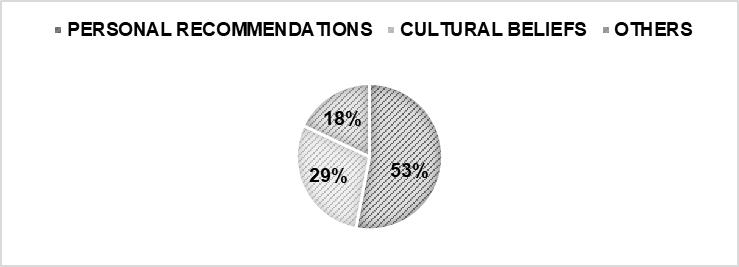

Results: Out of 322 survey respondents, only 17 reported using THM in the selected area. It revealed the total number of users were very low rate of adaptability (17/322=5.3%) only. Mostly used THM were 26 formulations finds in the dominant’s frequencies are widely utilized by different age groups and witnessed gender-wise (male-59% and female-41%) use patterned (fig. 2) and. The age group 41-60 y had the highest number of users, followed by the 20-40 y and above 61 y age groups (table 2). The pre-dominant of THM is in Kagyuk area (65%) than the Sajong (35%) out of n=17. Based on the type of formulations, solid (92%), followed by semi-solid (4%) and liquid (4%). The main reasons for its use include personal recommendation (58%) and cultural beliefs (29%); commonly treated (frequency of usability) (fig. 3) conditions include gastritis (23%), immunity booster (17%), followed by joint pain, neurological pain, tonsilitis, ovarian cyst, sinusitis, hypertension (11%), toothache, insomnia, constipation, anti-inflammatory (5%).

Conclusion: This survey highlights the important role of THM, showing low rate of user adaptability (5.3%) and the need for further research to understand barriers to adoption.

Keywords: Tibetan medicine, Sowa rigpa, Sikkim, Tibetan herbal medicine, Survey, Sajong-kagyud

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i12.56611 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Sowa Rigpa is a traditional medical system that has been practiced for over 2,500 y [1]. Sowa Rigpa is also known as "Science of healing," "Amchi medicine," or Tibetan medicine. It is a comprehensive medical system that has been an integral part of the cultural heritage of the Himalayan regions, including Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal, and parts of India. Rooted in Buddhist philosophy and practices, Sowa Rigpa reflects a synthesis of medical knowledge from ancient India, China, and Persia [2]. The foundational texts of Sowa Rigpa, such as the "Gyud-Zhi" (Four Tantras), provide extensive insights into its theoretical and practical aspects [3]. The fundamental scriptures of Sowa Rigpa are credited to Yuthok Yonten Gonpo the Younger, who lived in the 12th century. The most important of these works is the "Gyuzhi" or "Four Tantras," which provides a thorough framework for both theoretical and practical aspects of Tibetan medicine. The "Four Tantras" provide diagnostic methods and therapeutic practices, focusing on the balance of the three physiological humors: wind, bile, and phlegm [4]. Sowa Rigpa's diagnostic methods are precise and holistic, encompassing pulse reading, urine tests, and in-depth patient interviews to establish the patient's physical, mental, and spiritual health. Treatments are equally extensive, encompassing dietary and lifestyle changes, herbal medicines, and spiritual practices like as meditation and prayer. This holistic approach emphasizes the interdependence of the mind, body, and spirit in promoting health and well-being [5]. Sowa Rigpa's voyage to Sikkim-India, began in earnest around the mid-twentieth century. The Chinese conquest of Tibet in the 1950s led many Tibetan lamas and medical practitioners to escape their homeland, seeking sanctuary in neighboring countries such as India, Nepal, and Bhutan. These exiles brought with them not only their religious and cultural practices, but also medical knowledge. In Sikkim, these Tibetan practitioners settled in the early 1960s and founded many Kagyud monasteries in the Sajong-Kagyud area, Buddhist community area, practice and provide medical facilities to ensure the preservation and continuance of Sowa Rigpa [6, 7]. The Indian government recognized the value of Sowa Rigpa and formally recognized it as a traditional medicinal system. This accreditation aided the integration of Sowa Rigpa into India's national healthcare framework, allowing it to coexist with other traditional medicinal systems such as Ayurveda and Unani. Sowa Rigpa is now taught at numerous Indian institutions, notably the Central University of Tibetan Studies in Sarnath and the Men-Tsee-Khang (Tibetan medicinal and Astro Institute) in Dharamshala, ensuring that this old medicinal practice lives on [8].

The Namgyal Institute of Tibetology (NIT) is a significant organization in Sikkim that has been instrumental in protecting and advancing Sowa Rigpa literature and practices. The institute, which was founded in 1958 in Sikkim's capital city of Gangtok, is a leading hub for studies on Tibetan medicine and culture. A vast collection of Tibetan writings, including rare and old manuscripts pertaining to Sowa Rigpa, is kept at the NIT. In order to guarantee the preservation of traditional knowledge for upcoming generations, the institute also carries out research and provides practitioner training programs [9]. Working together, traditional practitioners and modern scholars have been able to better comprehend Tibetan medicine in a contemporary setting because of NIT. Its initiatives have made a substantial contribution to Sowa Rigpa's widespread acceptance as an effective medical system [10]. This present survey study aims to acquire the Knowledge, Practice, and Usability of Tibetan Herbal Medicine (Sowa Rigpa): A Community-Based Survey in the Sajong-Kagyud Area, Sikkim, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The main purpose of the survey was to find out the use of Tibetan medicine in the region Sajong–Kagyud, Gangtok Sikkim". The study was conducted in the Sajong-kagyud area Gangtok, Sikkim. This location was selected based on specific criteria relevant to the research, such as demographic characteristics, accessibility, and relevance to the study objectives [11, 12]. The inclusion criteria were not set as such, it was randomized screening, at least individual must reside in the study area and must be above 14 y. Individuals below the age of 14, frequently migrating people, some people did not response to the questions, who do not understand the local language, people who have not used the Tibetan medicines for past 2 y were excluded from the study to focus on the adult demographic. Further, study was narrowed based on those were taking the Tibetan medicines or not.

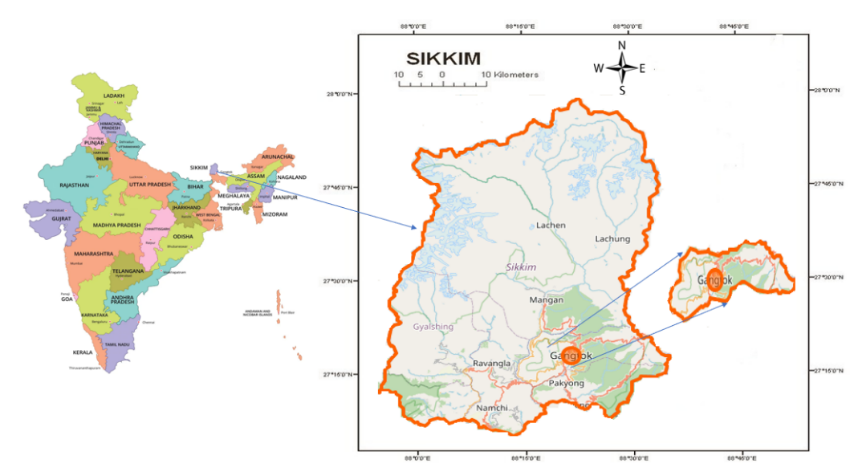

Fig. 1: Area of study

Selection of location

The study was conducted in the Sajong-kagyud area Gangtok, Sikkim. This location was selected based on specific criteria relevant to the research, traditional relationship-Buddhist community area, other are such as demographic characteristics, accessibility, and relevance to the study objectives.

Population and its sampling

The total population were 1997 individuals residing in this Gram Panchayat Unit region. From this population, a sample of 322 individuals was selected [13]. It revealed the total number of user (n=17), very low rate of adaptability of THM (17/322 = 5.3%) in the selected area. Individuals below the age of 14, frequently migrating people, some people did not response to the questions, who do not understand the local language, people who have not used the Tibetan medicines for past 2 y were excluded from the study to focus on the adult demographic. It was a six-month short survey which was done fulfill the Bachelor of Pharmacy project of 8th semester under Pharmacy Council of India education regulation. We obtained the institutional acknowledgement letter for conducting this survey study, Meno No./GPC/2025, and dated May 13th Sept, 2025 and Panchayat approval letter dated: 15.05.2024 as well as verbal consent was taken from the participants and included in the supplementary document.

Statistics and collection of data

The questionnaire for data collection was self-developed with some modification [14, 15]. The questionnaire was prepared in English language and questions were asked in English as well as the regional language (Nepali). The collected data were presented in a tabular and graphical presentations by using Microsoft excel 2013 application within the manuscript. For the inclusion of better data presentation, we have used Microsoft Excell 2023 64-Bit Edition, 15.0.5603.1000, was released on November 07, 2023 for the creation of graphs and tables within the manuscript.

Table 1: Pre-prepared questionnaires of the survey

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*The questionnaire was initially reviewed by the mentor (guide) to ensure its accuracy and relevance. The survey was then launched and conducted over a period of six months, during which participant responses were collected.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The data collected from the Sajong-Kagyud areas on the usage of Tibetan herbal medicine (Sowa Rigpa) revealed insightful patterns. The survey included 322 participants, selected from a population of 1997. Among these participants, 17 individuals specifically reported using Sowa Rigpa for chronic conditions, such as arthritis, gastritis, joint pains, chronic digestive problems, and neurological problems. It revealed the total number of users were very low rate of adaptability (17/322=5.3%) only. This subset provided detailed insights into their experiences, highlighting various usage patterns, effectiveness, and dosage practices. The demographic details and usage statistics provide a comprehensive overview of the current status and perception of Sowa Rigpa in these regions. The low adaptability in this area may be due to lack of awareness of the THM among the new generation and adults, accessibility is also another factor, belief in modern medicine, lack of awareness from THM practitioners to the new generation/adult. A significant aspect of the data collection involved visiting the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology (NIT) and its Sowa Rigpa clinic. During this visit, we had the opportunity to converse with Amchi (Tibetan Doctor) Zamyang Sherpa, specializing in Tibetan medicine. This interaction provided deeper insights into the practical applications and local acceptance of Sowa Rigpa [16, 17]. As per the previous studies, the Amchi's extensive experience and knowledge greatly enriched the data, highlighting the effectiveness and challenges faced in the broader implementation of these traditional practices. The Amchi helped clarify the uses, benefits, and proper dosages of these medicines, which added valuable context to my findings [18]. Maximum plants which are used in the THM were economically important and are having pharmacological potential, used in many polyherbal formulation too [19, 20]. In Sajong and Kagyud areas, the survey results showed varying degrees of usage across different age groups and genders. Notably, there were more female users compared to males. The age group of 41-60 y had the highest number of users (n=17), indicating a preference for traditional medicine among middle-aged individuals. The findings from the survey, coupled with insights from the visit to the NIT Sowa Rigpa clinic and the Amchi's input, paint a comprehensive picture of the role of Sowa Rigpa in the healthcare practices. If we compare with other Himalayan regions about the THM about Knowledge, Practice, and Usability (KPU), ancient Tibetan medical system uses 103 species-including 181 plants, 7 animals, and 5 minerals, only to cure liver disorders [21]. "Gso ba rig pa" is an accurate phrase for Tibetan medicine, often known as "Amchi medicine" in Nepal. In Nepal, there are four little gso ba rig pa schools. The dry Mustang region of Nepal, which borders Tibet, is where the Lo Kunphen school is situated. The school blends a contemporary curriculum with clinical and academic instruction in Tibetan medicine. In addition to cultivating medicinal plants, practical experience is regarded as an essential component of the training [22, 23]. Another study done in the Ladakh and Lahaul-Spiti region of Indian trans-Himalaya discussed the ingredients used in preparing various ethno-medicines to cure several ailments by Amchis inhabiting. During study, 337 plant species, 38 animal species, and 6 minerals were recorded. Of the 83 Amchis surveyed, 36 percent had students or disciples, mostly their own children. According to the report, it was found that declining of the Tibetan medical system in the study area might be due to the change in socioeconomic trends and the reluctance of the younger generation to pursue a career in Amchi [24, 25]. These finds in terms of user number are similar to ours, case of reduction on user number in Sajong and Kagyud areas can be correlated here. However, many other Himalayan regions are following THM since ages as compared to this locality, might be another reason of low adaptability in the selected area of study.

Table 2: Details of age group (n=17)

| S. No. | Age group | No. of users | No of non–users |

| 1. | 14-19 | 0 | 56 |

| 2. | 20-40 | 7 | 101 |

| 3. | 41-60 | 8 | 113 |

| 4. | 61-80 | 02 | 52 |

Fig. 2: Gender wise use of tibetan medicine (sowa rigpa) (n=17)

Fig. 3: Frequency of usability of tibetan medicine in different disease (n=17)

Table 3: Dosage forms, frequencies, and usability among the people of Sajong-Kagyud area

| S. No. | Name | No. of users | Category | Frequency | Usability |

| Latrae Ngathang | 3 | Granules | 1 Sachet morning 1/2 an hour before meal | Joint pain | |

| Rinched Drangjor Rilang Chenmo | 2 | Pills | New moon 1 pill and full moon 1 pill | Gastritis and spiritual influences | |

| Common Pills | 4 | Pills | Morning: 1 large pill Afternoon: 1 large pill and 1small Night; 3 mediums |

Joint pain, neurological pain | |

| Men Soom | 2 | Granules | 1 Sachet before meal | Gastritis | |

| Sonum Dhunpa | 1 | Liquid | 1-2 drops in cotton and apply in the tooth bd | Toothache | |

| Rinchen Jumar Nyernga | 1 | Pills | New moon 1 pill and full moon 1 pill | Anti-inflammatory, Immunity booster | |

| Common Pills | 1 | Pills | Morning: 3 small pills Afternoon: 3 large and 2 small Night: 2 small and 3 mediums |

Hypertension | |

| Trulthang | 1 | Coarse powder | 1 Sachet twice a day when needed | Cold and flu and headache, Immunity booster | |

| Men Nee | 2 | Powder | 1 Sachet morning 1/2 hour before meal | Abdominal pain | |

| Nyigug Sumthang | 1 | Granules | 1 Sachet every morning | Relieves insomnia | |

| Common Pills | 1 | Pills | Morning: 3 small and 3 large Afternoon: 3 small Night: 4 large |

Abdominal pain | |

| Rinchen Tsajor Chenmon | 1 | Pills | New moon 1 pill and full moon 1 pill | Gastritis | |

| Common Pills | 2 | Pills | Morning: 1 small and 2 mediums Afternoon: small 2 Night: 3 small and 1 large |

Gastritis | |

| Rinched Ratna Samphel | 1 | Pills | New moon 1 pill and full moon 1 pill | Neurological pain and spiritual influences | |

| Saab Gay | 1 | Cream | Apply one time both in morning and night | Skin rashes immunity booster |

|

| Sheche Drukpa | 2 | Pills | 3 Pills crushed and taken with warm water an hour before meal | Constipation | |

| Tobmen Chudue Gyatso | 1 | Granules | 1 Sachet before bed | Fatigue | |

| Men Chik | 2 | Granules | 1 Sachet 1/2 an hour before meal | Hypertension | |

| Gurkum Chupsum | 1 | Pills | 2 Pills after meal | Sinusitis | |

| Dorab | 1 | Pills | 2 Pills evening,30 min after meal | Sinusitis | |

| Olsey Nyernga | 1 | Pills | 2 Pills afternoon before meal | Ovarian cyst | |

| Garuda-5 | 1 | Pills | 2 Pills after dinner | Tonsilitis | |

| Gurgum-13 | 1 | Granules | 2 Pills afternoon | Tonsilitis | |

| Dasel Chenmo | 1 | Pills | 1 Pills in the morning after meal | Gastritis | |

| Ruta-6 | 1 | Pills | 2 Pills take on empty stomach | Gastritis | |

| Yukhung | 1 | Pills | 2 Pills after dinner | Ovarian cyst |

NOTE: Common pills mentioned above are of various types for different diseases and are provided by the Amchi (Tibetan doctor) based on their diagnosis. Unlike modern medicines, which are often packed in blisters or bottles, these pills are placed in moisture-resistant pouch of various sizes, such as small, medium, and large, and labeled with Tibetan names. The above showing information involved the many individuals are using multiple formulations. The numbers (e. g., "3 users" for Latrae Ngathang) can be considered as 3 instances of use reported by 17 people.

Fig. 4: Types of dosage form and percentage use

Fig. 5: Factors influencing the adoption and acceptance of THM

Table 4: Use of tibetan medicine in area sajong-kagyud (n=17)

| Area | Frequency | Percentage |

| Sajong | 6 | 35% |

| Kagyud | 11 | 65% |

CONCLUSION

This survey concludes that THM in a particular area of study showing low rate of user adaptability (17/322=5.3%) and the need for further research gap to understand barriers for adoption. In nutshell, this study highlights the significant role of THM (Sowa Rigpa) in the area for prominent healthcare practice in the future can be considered.

FUNDING

Nil

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

THM: Tibetan Herbal Medicines, NIT: Namgyal Institute of Tibetology

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

SB and TUK, responsible for Selection of this survey work. SB and GL, involved in major data collection from the field visit, face-to-face interview, and cross-sectional study from the selected area. S. B and TUK, responsible for the guiding the work till the completion and GL and SB, contributed for drafting, designing, formatting, referencing of this survey article and communicating with esteemed journal having good reputation in the scientific fields. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Gurmet P. Sowa-Rigpa: Himalayan art of healing. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2004 Apr;3(2):212-8.

Kloos S. The pharmaceutical assemblage: rethinking Sowa Rigpa and the herbal pharmaceutical industry in Asia. Curr Anthropol. 2017 Dec 1;58(6):693-717. doi: 10.1086/693896.

Takkinen J. Medicine in India and Tibet–reflections on buddhism and nature. Stud Orient Electron. 2011;109:151-62.

Clifford T. Tibetan Buddhist medicine and psychiatry: the diamond healing. Motilal Banarsidass Publ; 1994.

Meyer F. Theory and practive of Tibetan medicine. Oriental medicine: an illustrated guide to the Asian Arts of healing; 1995. p. 108-41.

Parfionovic UM, Dorje G, Meyer F. Tibetan medical paintings: illustrations to the blue beryl treatise of Sangye Gyamtso (1653‑1705). London: Serindia Publications; 1992.

Pordie L. Tibetan medicine in the contemporary world: global politics of medical knowledge and practice. London & New York: Routledge; 2008.

Roy V. Integrating indigenous systems of medicines in the healthcare system in India: need and way forward. In: Sen S, Chakraborty R, editors. Herbal medicine in India: indigenous knowledge, practice innovation and its value. Singapore: Springer; 2019 Sep 11. p. 69-87. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-7248-3_6.

Sharma Y. Art and architecture of the Buddhist monasteries of sikkim: a historical study of continuity and shifts (Doctoral dissertation, Sikkim University). Gangtok: Sikkim University; 2022.

Carlino O. Some aspects of religious spirituality in medicine: an investigation into the dialogue between biomedicine and Tibetan medicine via Christianity and Buddhism. [Master’s thesis]. Venice: Universita Ca Foscari; 2022.

Bhutia KN, Basnett DK, Bhattarai A, Bhutia S. Herbal products sold in Sikkim Himalaya region India: a mini survey. GJMPBU. 2023 Jan 1;18:14. doi: 10.25259/GJMPBU_43_2022.

Tamang M, Pal K, Kumar Rai S, Kalam A, Rehan Ahmad S. Ethnobotanical survey of threatened medicinal plants of West Sikkim. Int J Bot Stud. 2017 Nov;2(6):116-25.

Jamous RM, Sweileh WM, El Deen Abu Taha AS, Zyoud SH. Beliefs about medicines and self-reported adherence among patients with chronic illness: a study in Palestine. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2014 Jul 1;3(3):224-9. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.141615, PMID 25374859.

Loizzo JJ, Blackhall LJ, Rapgay L. Tibetan medicine: a complementary science of optimal health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 Aug;1172(1):218-30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1393.008, PMID 19743556.

Lhamo N, Nebel S. Perceptions and attitudes of Bhutanese people on Sowa Rigpa, traditional Bhutanese medicine: a preliminary study from Thimphu. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011 Jan 10;7(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-3, PMID 21457504.

McGrath WA. Buddhism and medicine in Tibet: origins, ethics and tradition [Doctoral dissertation] University of Virginia; 2017.

Czaja O. The administration of Tibetan precious pills: efficacy in historical and ritual contexts. Asian Med (Leiden). 2015 Oct 3;10(1-2):36-89. doi: 10.1163/15734218-12341350, PMID 27980504.

Besch NF. Tibetan medicine off the roads: modernizing the work of the amchi in spiti. Heidelberg: Ruprecht-Karls-Universitat Heidelberg; 2006. doi: 10.11588/heidok.000078932006.

Nath RA, Kityania SI, Nath DE, Talkudar AD, Sarma GA. An extensive review on medicinal plants in the special context of economic importance. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(2):6-11. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i2.46073.

Athira RN, Thamara K, Kumar SO. Pharmacological potential of polyherbal ayurvedic formulations a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(11):14–20. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i11.45703.

Li Q, Li HJ, Xu T, Du H, Huan Gang CL, Fan G. Natural medicines used in the traditional Tibetan medical system for the treatment of liver diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Jan 30;9:29. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00029, PMID 29441019.

Shankar PR, Paudel R, Giri BR. Healing traditions in Nepal. J Am Assoc Integr Med. 2006 Mar 16.

Craig SR. A crisis of confidence: a comparison between shifts in Tibetan medical education in Nepal and Tibet. In: Schrempf M, editor. Soundings in Tibetan Medicine: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives. Leiden: Brill; 2007. p. 127-54.

Adhikari BS. Sowa-Rigpa: a healthcare practice in Trans-Himalayan region of Ladakh, India. SDRP-JPS. 2017;2(1):45-52. doi: 10.25177/JPS.2.1.3.

Kala CP. Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in the trans-Himalayan region of India. Curr Sci. 2005 Oct 25;89(8):1331-8.