Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 12, 42-48Original Article

PROPHYLACTIC EFFICACY OF GLYCOSIDES RICH STANDARDIZED FENUGREEK SEED EXTRACT ON EXPERIMENTAL RENAL INTERSTITIAL FIBROSIS IN MICE

PRASAD THAKURDESAI1*, ROHINI PUJARI2

1*Department of Scientific Affairs. 1 Rahul Residency, Off Salunke Vihar Road, Kondhwa-411048, Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2Department of Pharmacology, Dr. Vishwanath Karad MIT World Peace University, Kothrud, Pune, India

*Corresponding author: Prasad Thakurdesai; *Email: prasad@indusbiotech.com

Received: 28 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 15 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study investigated the effects of glycosides-rich standardized fenugreek seed extract (SFSE-G) in a mouse model of “unilateral ureteral obstruction” (UUO)-induced renal fibrosis.

Methods: UUO was performed in 32 female mice (C57BL/6 strain) and randomized into groups of eight mice each. A separate group of eight mice (sham control) underwent sham operation with no UUO surgery. Mice were orally administered vehicle (distilled water) or SFSE-G at doses of 30, 60, or 100 mg/kg twice daily for 13 days. Various biochemical, histological, and gene expression-related measurements were conducted on day 14 after euthanasia, and body weights were measured daily.

Results: Subacute oral administration of SFSE-G showed dose-dependent significance (p<0.05, P<0.01) to reduce UUO-induced elevation of blood urea nitrogen levels and attenuated histopathological changes, including tubular injury and collagen deposition. Quantitative PCR revealed that SFSE-G downregulated oxidative stress-and fibrosis-related gene expression of markers such as “α-smooth muscle action”, “nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2”, and “heme oxygenase-1”. Although SFSE-G-treated mice showed a downward trend against UUO-induced increases in hydroxyproline content and gene expression of “transforming growth factor-β1” and tissue inhibitor of collagen type 1 and metalloproteinase-1, the differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion: SFSE-G exerts fibrosis preventive and renoprotective effects in UUO-induced renal fibrosis, probably by modulating oxidative stress and fibrotic pathways.

Keywords: Fenugreek, Glycosides, Renal interstitial fibrosis, Standardized extract, Unilateral ureteral obstruction

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i12.56661 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

The renal fibrosis is a maladaptive wound-healing response that involves an excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM), a critical component of almost all chronic kidney diseases, leading to permanent organ failure and “end-stage renal disease” (ESRD) [1]. This pathological process results from a progressive replacement of functional parenchyma with scar tissue, which obliterates the standard kidney architecture.

Renal fibrosis, which is characterized by a reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), is associated with several systemic problems, such as fluid overload, persistent hypertension, hyperkalemia and anaemia [2], increased risk of heart diseases, impaired immune function, susceptibility to infection, and neurological disturbances [3]. Therefore, strategies that inhibit or reverse renal fibrosis are essential for optimizing outcomes and for reducing the burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

The primary cause of renal fibrosis can be classified as either obstructive or immune-mediated [4]. Obstructive fibrosis (also known as Renal Interstitial Fibrosis (RIF)) results from persistent urinary tract obstructions, such as nephrolithiasis, whereas immune-mediated fibrosis may develop in response to systemic autoimmune diseases or glomerulonephritis [5]. Regardless of the causes that contribute to myofibroblast activation and ECM accumulation, common fibrogenic pathways involve the “transforming growth factor-beta 1” (TGF-β1), oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [3].

RIF is a key therapeutic target because it can be diagnosed and treated early, and pharmacological interventions to resolve obstruction can prevent renal damage, maintain renal function, and prevent progression to ESRD [2]. Other strategies that target metabolic abnormalities, inflammation, TGF-β1 signalling, oxidative stress, and ECM accumulation are likely to prevent fibrogenesis and improve renal functions [6].

Although current therapeutic approaches predominantly offer supportive care and target symptoms, natural products have been shown to possess a renoprotective potential for prophylaxis [7]. Considering the multifactorial nature of CKD progression and the limitations inherent to current treatments, novel plant-derived natural compounds containing bioactive natural products represent a promising strategy for developing targeted interventions aimed at preventing RIF. These products may serve as either primary or adjunctive therapies to address the physiological targets associated with RIF and mitigate the progression of CKD [8, 9].

The seeds of Fenugreek, Trigonella foenum-graecum Linn (Family: Fabaceae) is extensively used in traditional medicine. Prior research involving animal models with fenugreek seed extracts has indicated positive effects on factors associated with renal fibrosis, including the enhancement of insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism [10], antioxidant properties [11], and preventive effects against kidney stone formation [12, 13].

Among the various fenugreek seed products, “glycosides-rich standardized fenugreek seed extract” (SFSE-G) has been shown to inhibit TGF-β1 signaling pathways [14], lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines [15], slow the processes of ECM buildup, and kidney fibrosis. The fenugreek glycosides exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by downregulating cytokines and interleukins in prostate tissue remodeling and hyperplasia [3]. SFSE-G has shown anti-fibrotic properties by activating the “nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2” (Nrf2), to decrease inflammation and lung fibrosis in rats induced by bleomycin [16]. Furthermore, SFSE-G provides liver protection by reducing oxidative stress and influencing the expression of the “farnesoid X receptor” (FXR), thereby enhancing bleomycin-induced liver fibrosis [14]. In addition, SFSE-G is characterized by a strong safety profile, as demonstrated by extensive regulatory toxicological assessments [17, 18]. These results suggest that SFSE-G could offer a comprehensive approach to mitigating renal fibrosis, especially of RIF type, and justify further in-depth research.

Therefore, the main objective of the present work is to investigate the potential fibrosis preventive efficacy and the possible mechanism of action of SFSE-G in “Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction” (UUO)-induced RIF in mice because of its high reproducibility, robustness, and ability to replicate key pathological features [19].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All present work were carried out with full compliance with the Animal Use Guidelines set by the Japanese Pharmacological Society. All the protocols were approved (No. SP_MNP050-1208-0) by the “Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee” of Stelic Institute and Co., Tokyo, Japan, a contract research organization. Forty pathogen-free verified female mice (C57BL/6, about 9 w old, weights 20-25 g) were procured from “Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan)”. The mice were maintained for at least 7 d in a controlled environment (23 ± 2 °C temperature, 45 ±10% of relative humidity, 20 ± 4 Pa air pressure, 12h: 12h light/dark cycle).

Materials

The test material, SFSE-G, was a dry powder supplied by Indus Biotech Limited (Pune, India). Distilled water was used to prepare the stock solutions, which were stored at 4 °C for future use. SFSE-G was administered orally via gavage at doses of 30, 60, or 100 mg/kg, two times a day, between 8 am and 9 am and 5pm and 6pm, except on day 0, when it was administered once. Sodium pentobarbital (Sedalphorte®; Saludy Bienestar Animal S. A. de C. V., Mexico) was used for both anesthesia and euthanasia, and Formalin and Schiff’s reagent as “Periodic Acid-Schiff” (PAS) staining was procured from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). Picrosirius red (PSR) solution was obtained from Waldeck GmbH and Co. KG (Münster, Germany). An anticoagulant, Novo-Heparin, was produced from Mochida Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan).

Experimental design

The mice were allocated into five distinct experimental groups, each consisting of eight animals, as outlined below: (A) sham control, in which the surgical procedure was performed without UUO; (B) UUO control, in which mice underwent UUO surgery and received only vehicle treatment. The other 3 groups (C, D, and E) were treated with SFSE-G at doses of 30 mg/kg, 60 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg with UUO and named SFSE-G (30), SFSE (60), and SFSE-G (100), respectively. Body weight (BW) was recorded daily. The treatments were administered 1–4 h before UUO (day 0) and twice daily thereafter from day 1 to day 13.

UUO was induced under anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital using 4-0 silk as previously reported [20, 21]. After closing the peritoneum and skin with stitches, mice were kept in clean cages and monitored until recovery. The sham-operated mice underwent identical surgical exposure without ligation. Postoperatively, animals were returned to clean cages until complete recovery. Seven days after UUO, blood and kidney samples were collected after sacrifice using a sodium pentobarbital overdose.

Effects on kidney function in biochemistry

The effects on kidney function were assessed by plasma biochemistry. Blood was drawn via cardiac puncture under anesthesia and collected in polypropylene tubes with anti-coagulant, Novo-Heparin. The samples were centrifuged (1,000 ×g; 15 min; 4 °C), to separate supernatant, and maintained at -80 °C, until analysis by biochemistry analyser (FUJI DRI-CHEM 700, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) to measure the levels of “plasma creatinine” (CRE) and "blood urea nitrogen" (BUN).

Kidney hydroxyproline (HP) content

The HP content of kidney samples (17-40 mg) and protein concentrations were measured using the alkaline-acid hydrolysis method, and bicinchoninic acid assay methods (kit of “Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA”)as reported previously [21, 22]. HP values were expressed as mg per mg of protein.

Histology

Kidney sections were fixed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and PAS-stained during Schiff’s reagent or PSR-stained with PSR solution as per the manufacturer’s instructions and as reported earlier [20, 21]. The interstitial fibrosis areas of the PSR-stained kidney sections were quantified using bright-field images of the corticomedullary region and captured using a digital camera (“DFC280 model, Leica, Solms, Germany”). PSR-positive areas in five fields per section were measured using the ImageJ software (“National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA”). All slides were coded for analysis.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA extraction reagent (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) was used for RNA extraction from the left kidney as per manufacturer's instructions. The gene expression measurement of Nrf2,“Heme oxygenase-1” (HO-1), “alpha-smooth muscle actin” (α-SMA), TGF-β, “Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1” (TIMP-1) and “Collagen type 1” was accomplished using “Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction” (PCR) for “DICE thermal cycler” (TP800, Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) and “SYBR premix Taq” (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) as per manufacturer’s instructions. The expression level was represented as relative expression by comparison with the reference gene, “glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase” (GAPDH).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses, presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM), were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test for gene expression analysis and the Bonferroni Multiple Comparison Test for the remaining data. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. These analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Base software version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, USA).

RESULTS

Effects on BW, Kidney weight (KW) and relative KW

There were no significant changes in BW across all groups at the time of sacrifice, indicating that UUO surgery or SFSE-G treatment did not significantly affect overall animal health or body mass (table 1). No significant signs of toxicity, morbidity, or mortality were observed in any group during daily monitoring of clinical signs and behavior.

On the day of sacrifice, UUO control group showed a significant increase in KW and relative KW (ratio of KW to BW) as compared to Sham control. However, SFSE-G treatment did not show significant effects on UUO-induced changes in KW or Relative KW compared to the UUO control (Table 1).

Table 1: Effect of SFSE-G on wights and biochemical analysis

| Sham control | UUO control | SFSE-G (30) | SFSE-G (60) | SFSE-G (100) | |

| BW (g) | 19.90±0.20 | 19.20±0.40 | 19.30±0.20 | 19.30±0.40 | 19.60±0.40 |

| KW (mg) | 123.0±4.00 | 293.0±27.0### | 309.00±20.0 | 301.0±40.0 | 280.00±23.0 |

| Relative KW | 6.16±0.16 | 15.36±1.56### | 16.06±1.04 | 15.68±2.10 | 14.31±1.06 |

| CRE (mg/dl) | 0.10±0.00 | 0.10±0.00 | 0.10±0.00 | 0.10±0.00 | 0.10±0.00 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 21.60±1.30 | 37.30±1.80### | 33.50±1.30 | 31.60±1.50* | 30.30±1.40** |

| HP (µg/mg of TP) | 1.47±0.08 | 5.27±0.24### | 5.24±0.30 | 4.56±0.53 | 5.24±0.29 |

n=8, fig. in parentheses show dose in mg/kg. Data shown as mean±SEM, analyzed by One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test. ns-not significant, ###P<0.001 (vs. Sham control), *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (vs. UUO control). BW: Body weight; KW: Kidney weight; CRE: Plasma creatinine; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; HP: Kidney hydroxyproline; TP: Total protein

Effects on kidney function

As shown in , plasma CRE levels remained unchanged across all groups, including Sham, UUO control, and SFSE-G-treated groups. However, BUN levels were significantly higher in the UUO control than in the Sham Control (P<0.001). SFSE-G (at 60 and 100 mg/kg, but not at 30 mg/kg) significantly (P<0.05, and P<0.001, respectively) reduced the elevated BUN levels (vs. UUO control), indicating its beneficial effect on renal function table 1.

Effects on HP content

Kidney HP content, a direct biochemical marker of collagen deposition and fibrosis, increased significantly (P<0.001) in UUO control vs. Sham Control). While SFSE-G treatment at all doses showed a trend towards the prevention of UUO-induced elevated HP content, the differences from UUO control values were not statistically significant ().

Effects on kidney during histology

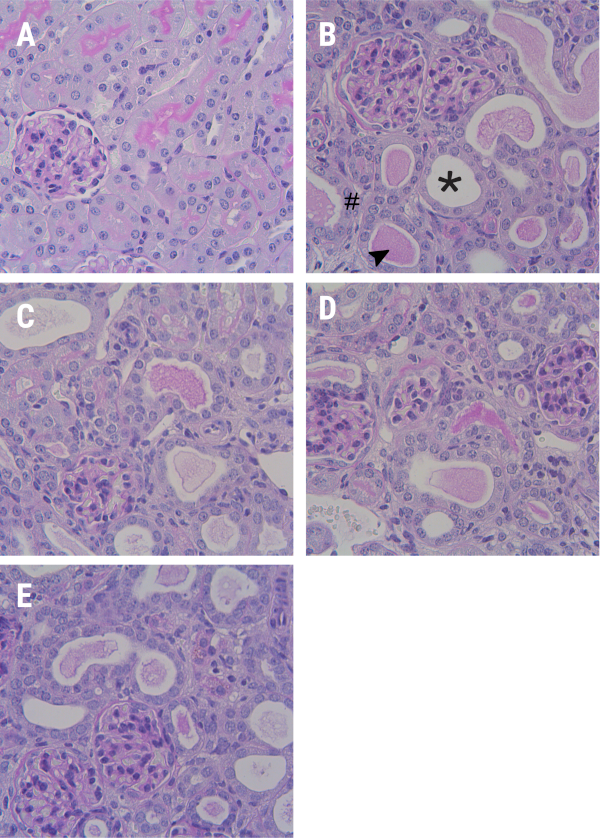

Histopathological examination of the kidney sections provided visual evidence of the effects of the treatments. showed sample photomicrographs of PAS-stained kidney sections and revealed that the UUO control group (fig. 1B) exhibited significant tubular dilation (shown as (* asterisk), atrophy, (shown as # hash) and intratubular cast formation (shown as arrow heads), in both the cortical and medullary regions (but not in the glomeruli), indicating severe renal damage. However, the sham control group (fig. 1A) showed a normal morphology. The kidney samples of the SFSE-E-treated groups (fig. 1C to fig. 1E) showed a reduced extent of these pathological changes in one sample from SFSE-G (30 and 60 mg/kg each) and two samples of SFSE-G (100 mg/kg) groups, suggesting protective effects on tubular morphology against UUO (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Representative images of kidney sections (cortices) stained with Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) (A) Sham Control group, showing normal morphology; (B) UUO Control group, showing tubular dilation (* asterisk), atrophy (# hash), and intratubular cast formation (arrowheads, ). (C-E) SFSE-G (30, 60, and 100 mg/kg)-treated groups showed less damage. UUO, Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction, Stain: PAS, Magnification: 400X

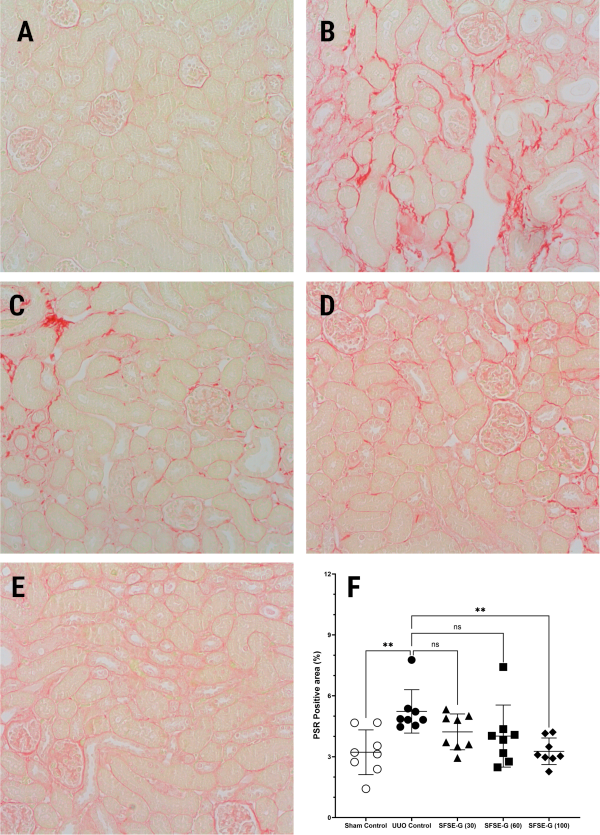

Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections stained with PSR () demonstrated extensive collagen deposition (stained as intense red color) in the tubulointerstitial sections of kidneys from of UUO control (fig. 2B) (but not from Sham Control (fig. 2A), confirming the development of significant RIF. SFSE-G treatment resulted in dose-dependent protection, with visibly less collagen deposition (vs. UUO control), suggesting a fibrosis-preventive potential (fig. 2C to fig. 2E).

The % PSR-positive area (fig. 2F) served as a quantitative measure to evaluate the level of fibrosis in kidney specimens. The PSR-positive area (%) of kidney samples from UUO control (5.23±0.38) was significantly (P<0.01) more vs. Sham Control (3.22±0.39), confirming collagen deposition. Treatment with SFSE-G (30 and 60 mg/kg) showed reduced values (4.23±0.31 and 4.02±0.54, respectively) of the PSR-positive area (%) as compared to that of UUO control, although statistical significance was not reached. However, kidney samples of mice from the SFSE-G (100 mg/kg) treated group showed PSR-positive area (%) of 3.27±0.23, which was significantly less (P<0.01) than that of UUO control (fig. 2F).

Effects on gene expression during qPCR

The mRNA expression (relative to GAPDH) of Nrf2, HO-1, α-SMA, TGF-β, TIMP-1, and collagen type 1 in kidney samples from the UUO control group was significantly upregulated (vs. sham control) (Table 2). Significant downregulation of mRNA expression (relative to GAPDH) of Nrf2 by SFSE-G (30 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg), HO-1 by SFSE-G (60 mg/kg), and α-SMA by SFSE-G (60 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) was observed. However, the reduction in mRNA expression (relative to GAPDH) of TGF-β, TIMP-1 and Collagen Type 1 in SFSE-G-treated group was not found to be statistically significant compared to that of UUO control (Table 2).

Fig. 2: Representative images of kidney sections (corticomedullary area) stained with picro-sirius red (PSR) (A) Sham control group showing normal morphology, (B) UUO Control group showing extensive collagen deposition (more intense red color) in the tubulointerstitial region. (C–E) SFSE-G (30, 60, and 100 mg/kg)-treated groups, showing a lower extent of deposition. UUO: Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction, Stain: PSR, Magnification: 400X

Table 2: Effect of SFSE-G on relative gene expression levels in kidney tissues

| Protein | Relative expression to GAPDH (Mean±SEM) | ||||

| Sham control | UUO control | SFSE-G (30) | SFSE-G (60) | SFSE-G (100) | |

| Nrf2 | 1.00±0.03 | 3.02±0.09### | 2.48±0.14* | 3.31±0.16* | 3.08±0.31 |

| HO-1 | 1.00±0.06 | 3.20±0.21### | 3.41±0.53 | 4.93±0.47** | 4.54±0.81 |

| α-SMA | 1.00±0.05 | 16.56±1.20### | 13.62±2.78 | 12.39±1.21* | 11.13±1.64* |

| TGF-β | 1.00±0.05 | 15.50±0.96### | 12.64±1.01 | 15.92±1.38 | 12.89±1.72 |

| TIMP-1 | 1.00±0.14 | 816.30±74.68### | 543.90±82.22 | 647.10±75.60 | 609.00±96.81 |

| Collagen type 1 | 1.00±0.05 | 22.19±1.86### | 20.10±2.30 | 27.03±2.85 | 21.37±3.02 |

n=8, fig. in parentheses show dose in mg/kg. Data shown as mean±SEM, analyzed by separate Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA followed by Mann-Whiney ‘U’ test.### P<0.001 (vs. Sham control).* P<0.05, ** P<0.01 (vs. UUO control), Nrf2: “Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2”; HO-1: “Heme oxygenase-1”; α-SMA: “alpha 2, smooth muscle actin”, aorta; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; TIMP-1: Tissue inhibitor of “metalloproteinase 1”; Collagen Type 1: “collagen, type I, alpha 2 chain”; GAPDH: “Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase”.

DISCUSSION

This study explored the protective effects against kidney damage and the prevention of fibrosis offered by SFSE-G, a standardized extract rich in glycosides from fenugreek seeds, in a mouse model of RIF caused by UUO, which mimics many pathological features in the progression of human CKD [23]. Therefore, RIF with fibroblast activation, my fibroblast differentiation, and profibrotic cytokine signaling have emerged as critical targets for therapeutic intervention. The findings of this study indicate the successful prevention of UUO-induced fibrotic changes, like elevated BUN levels, increased kidney weight, and significant histopathological changes, including tubular injury and extensive collagen deposition, by subacute oral administration of SFSE-G. These beneficial effects were further supported by gene expression modulation of key genes related to oxidative stress, inflammation, my fibroblast activation, and fibrosis, such as Nrf2, HO-1, and α-SMA.

The present study utilized UUO, a critical and extensively studied experimental model, to induce and mimic the progression of obstructive nephropathy and subsequent kidney damage observed in humans [19]. The UUO model involves ligation of one ureter, which triggers a series of events, including tubular atrophy, interstitial inflammation, oxidative stress, and ECM deposition, ultimately leading to RIF [24, 25]. The mechanism involves physical blockage of the ureter, leading to hydro nephrosis and a cascade of detrimental cellular and molecular events within the kidney [19].

Body weight is intricately linked to CKD and related disorders, such as RIF [26]. The study results did not show any significant changes in body weight across groups, suggesting that neither UUO nor SFSE-G treatment substantially affected the overall health of the animals. Furthermore, it also showed the absence of notable toxicity, morbidity, and mortality with SFSE-G treatment in UUO-induced mice. The results indicated that SFSE-G prevented UUO-induced changes in KW or relative KW, indicating its beneficial effects in mitigating obstructive injury. An increase in kidney weight often reflects adaptive hypertrophy due to the compensatory mechanism in response to renal injury, particularly in UUO, which can initiate a cascade of pathological changes, including inflammation and dysregulated ECM production, contributing significantly to RIF [27]. An increase in relative KW can imply maladaptive changes that might forecast deteriorating kidney function, especially in the context of chronic obstruction, where ongoing injury and inflammation are present [28]. However, the SFSE-G did not significantly affect KW or relative KW in this study.

Elevated CRE levels reflect impaired renal clearance in the context of human fibrosis. However, in early-stage renal damage in animals, such as in UUO model, plasma CRE levels may not increase significantly, due to the compensatory function of the contralateral kidney [29] as seen in the present study. BUN levels in the UUO control group were markedly increased, suggesting compromised renal function, nitrogen-related waste buildup, and reduced renal excretion [30]. In UUO, progressive RIF, nephron loss, and reduced renal perfusion, resulted in the accumulation of urea and other nitrogenous chemicals in the blood [31]. Treatment with SFSE-G significantly reduced BUN levels, indicating its protective effects against renal dysfunction by preserving nephron function.

Kidney HP level, a marker of fibrosis and collagen accumulation, showed significant increase in UUO control group, indicating severe fibrotic changes. Excessive ECM deposition, particularly collagen deposition, is a hallmark of progressive tubulointerstitial damage in RIF and CKD. Elevated HP levels reflect the severity of fibrotic remodeling, contributing to nephron loss, decreased filtration, and ultimately, end-stage renal dysfunction. Even though statistical significance is absent, the trend towards reduced HP content following SFSE-G treatment suggests a potential anti-fibrotic effect. The potential anti-fibrotic efficacy of SFSE-G in preserving renal tissue integrity and slowing the progression of RIF is substantiated by the histological results of this study, which show that SFSE-G confers structural protection and exerts a meaningful fibrosis-preventive effect.

Histopathological changes in tubular architecture and ECM accumulation are hallmark features of RIF and CKD progression [32]. Tubular atrophy and RIF impair nephron function and reduce filtration capacity, leading to irreversible damage and progression [33]. PSR staining is the gold standard method for evaluating collagen deposition and reflects the severity of fibrotic transformation in the renal parenchyma [34]. In our study, histological analysis using PAS staining revealed marked tubular injury, indicated by dilation, atrophy, and intratubular cast formation in the UUO control group, whereas SFSE-G treatment demonstrated visible protection against these structural damages. PSR staining is widely used to quantify the extent of fibrillar collagen deposition, especially types I and III, indicating renal fibrogenesis in tubulointerstitial fibrosis [35]. In this study, SFSE-G treatment resulted in dose-dependent prevention of UUO-induced increases in collagen deposition and fibrotic areas, achieving statistical significance at the 100 mg/kg dose, indicating protection from renal fibrogenesis. Collagen buildup is associated with the activation of myofibroblasts and the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, both of which play a crucial role in the progression of fibrosis. The possible molecular pathways underlying the anti-fibrotic efficacy of SFSE-G might be the inhibition of key profibrotic pathways, such as myofibroblast activation and TGF-β signaling.

The UUO control group exhibited significant upregulation in renal mRNA expression of Nrf2, HO-1, α-SMA, TGF-β, and collagen type 1, TIMP-1 indicating stimulation of oxidative stress and fibrotic signaling pathways after UUO induction, as previously reported [36]. In RIF, TGF-β acts as a central profibrotic cytokine driving fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation and collagen synthesis [23], while α-SMA and collagen type 1 are direct markers of fibrogenic activation [37]. TIMP-1 impedes matrix degradation, contributes to ECM accumulation, exacerbating fibrosis[38]. Nrf2 and HO-1, though typically cytoprotective, can be upregulated in response to UUO, which can induce oxidative stress and tissue injury [39]. Treatment with SFSE-G significantly downregulated Nrf2, HO-1, and α-SMA, suggesting its dual action in reducing fibrotic and oxidative stress responses.

The significant downregulation of α-SMA, a myofibroblast activation marker, indicates reduced fibroblast transdifferentiation, which is a central event in tubulointerstitial fibrosis [40]. However, the role of the TGF-β/Smad signaling cascade, which is pivotal in driving ECM production and collagen accumulation, cannot be ruled out because the observed downward trends for TGF-β and collagen type I expression preserve the renal architecture. The reduced PSR-positive area in histology also supports the hypothesis of the prevention of collagen deposition by SFSE-G. In addition, SFSE-G treatment caused a significant downregulation of Nrf2 and HO-1 gene expression at low doses, suggesting its capacity to reduce oxidative stress burden and provide renoprotective and fibrosis preventive action.

CONCLUSION

The present study demonstrated the fibrosis-preventive efficacy of subacute oral administration of SESE-G in UUO, an animal model of RIF, through the modulation of fibrotic and oxidative stress pathways. Further studies, such as well-designed clinical trials and comprehensive molecular mechanism studies, are needed to develop SFSE-G as a targeted intervention for RIF in CKD management.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the Stelic Institute and Co., Tokyo, Japan, for research services.

FUNDING

This study was funded by Indus Biotech Limited (Pune, India).

ABBREVIATIONS

α-SMA-alpha-smooth muscle actin, ANOVA-Analysis of variance, BCA-Bicinchoninic acid assay, BUN-blood urea nitrogen, BW-body weights, CKD-chronic kidney disease, CRE-plasma creatinine, ECM-extracellular matrix, ESRD-end-stage renal disease, FXR-farnesoid X receptor, GADPH-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GFR-glomerular filtration rate, HO-1-Heme oxygenase-1, HP-hydroxyproline, IL-1β-Interleukin-1 beta, IL6-Interleukin 6, KW-kidney weight, Nrf2-Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, PAS-Periodic Acid-Schiff, PCR-Polymerase Chain Reaction; PSR-Picrosirius red; qPCR-Quantitative PCR; RNA-Ribonucleic acid; SEM-standard error of means, SFSE-G-glycosides rich standardized fenugreek seeds extract, TGF-β-transforming growth factor-beta 1, TIMP-1-Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1, TNF-α-Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha, UUO-unilateral ureteral obstruction

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

PT were involved in the conception and design of the study, project supervision, and manuscript reviewing, and approving. RP was involved in administration, writing, reviewing, and approving the manuscript. All authors have significantly and directly contributed intellectually to the project and have approved the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

This study was supported by Indus Biotech Limited, Pune, India, but had no role in the collection and analysis of data.

REFERENCES

Huang R, Fu P, Ma L. Kidney fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):129. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01379-7, PMID 36932062.

Yan MT, Chao CT, Lin SH. Chronic kidney disease: strategies to retard progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(18):10084. doi: 10.3390/ijms221810084, PMID 34576247.

Antar SA, Ashour NA, Marawan ME, Al Karmalawy AA. Fibrosis: types, effects markers mechanisms for disease progression and its relation with oxidative stress immunity and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):4004. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044004, PMID 36835428.

Imig JD, Ryan MJ. Immune and inflammatory role in renal disease. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(2):957-76. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120028, PMID 23720336.

Ma L, Liu D, Yu Y, Li Z, Wang Q. Immune-mediated renal injury in diabetic kidney disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1587806. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1587806, PMID 40534883.

Kalantar Zadeh K, Bellizzi V, Piccoli GB, Shi Y, Lim SK, Riaz S. Caring for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: dietary options and conservative care instead of maintenance dialysis. J Ren Nutr. 2023;33(4):508-19. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2023.02.002, PMID 36796502.

Yaribeygi H, Simental Mendia LE, Butler AE, Sahebkar A. Protective effects of plant-derived natural products on renal complications. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(8):12161-72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27950, PMID 30536823.

Mohany M, Ahmed MM, Al Rejaie SS. Molecular mechanistic pathways targeted by natural antioxidants in the prevention and treatment of chronic kidney disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;11(1):15. doi: 10.3390/antiox11010015, PMID 35052518.

Zhou Z, Qiao Y, Zhao Y, Chen X, Li J, Zhang H. Natural products: potential drugs for the treatment of renal fibrosis. Chin Med. 2022;17(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13020-022-00646-z, PMID 35978370.

Fakhr L, Chehregosha F, Zarezadeh M, Chaboksafar M, Tarighat Esfanjani A. Effects of fenugreek supplementation on the components of metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Pharmacol Res. 2023;187:106594. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106594, PMID 36470549.

Kim MJ, Sinam IS, Siddique Z, Jeon JH, Lee IK. The link between mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia: an update focusing on the role of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4. Diabetes Metab J. 2023;47(2):153-63. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2022.0305, PMID 36635027.

Laroubi A, Touhami M, Farouk L, Zrara I, Aboufatima R, Benharref A. Prophylaxis effect of Trigonella foenum graecum L. seeds on renal stone formation in rats. Phytother Res. 2007;21(10):921-5. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2190, PMID 17582593.

Ahsan SK, Tariq M, Ageel AM, Al Yahya MA, Shah AH. Effect of Trigonella foenum graecum and Ammi majus on calcium oxalate urolithiasis in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1989;26(3):249-54. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90097-4, PMID 2615405.

Kandhare AD, Bodhankar SL, Mohan V, Thakurdesai PA. Glycosides based standardized fenugreek seed extract ameliorates bleomycin induced liver fibrosis in rats via modulation of endogenous enzymes. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2017;9(3):185-94. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.214688, PMID 28979073.

Kandhare AD, Bhaskaran S, Bodhankar SL. Potential of fenugreek in management of fibrotic disorders. In: Ghosh D, Thakurdesai P, editors. Fenugreek: traditional and modern medicinal uses. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2022. p. 307-19. doi: 10.1201/9781003082767-23.

Kandhare AD, Bodhankar SL, Mohan V, Thakurdesai PA. Effect of glycosides based standardized fenugreek seed extract in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats: decisive role of Bax, Nrf2, NF-κB, Muc5ac, TNF-α and IL-1β. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;237:151-65. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.06.019, PMID 26093215.

Deshpande PO, Mohan V, Pore MP, Gumaste S, Thakurdesai PA. Prenatal developmental toxicity study of glycosides-based standardized fenugreek seed extract in rats. Pharmacogn Mag. 2017;13(49) Suppl 1:S135-41. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.203978, PMID 28479738.

Deshpande P, Mohan V, Thakurdesai P. Preclinical safety assessment of glycosides-based standardized fenugreek seeds extract: acute subchronic toxicity and mutagenicity studies. J App Pharm Sci. 2016;6(9):179-88. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2016.60927.

Norregaard R, Mutsaers HA, Frokiær J, Kwon TH. Obstructive nephropathy and molecular pathophysiology of renal interstitial fibrosis. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(4):2827-72. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2022, PMID 37440209.

Sunami R, Sugiyama H, Wang DH, Kobayashi M, Maeshima Y, Yamasaki Y. Acatalasemia sensitizes renal tubular epithelial cells to apoptosis and exacerbates renal fibrosis after unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286(6):F1030-8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00266.2003, PMID 14722014.

Lefebvre E, Moyle G, Reshef R, Richman LP, Thompson M, Hong F. Antifibrotic effects of the dual CCR2/CCR5 antagonist cenicriviroc in animal models of liver and kidney fibrosis. PLOS One. 2016;11(6):e0158156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158156, PMID 27347680.

Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150(1):76-85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7, PMID 3843705.

Panizo S, Martinez Arias L, Alonso Montes C, Cannata P, Martin Carro B, Fernandez Martin JL. Fibrosis in chronic kidney disease: pathogenesis and consequences. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(1):408. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010408, PMID 33401711.

Zhao HY, Li HY, Jin J, Jin JZ, Zhang LY, Xuan MY. L-carnitine treatment attenuates renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36 Suppl 1:S180-95. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2019.413, PMID 32942841.

Jiang YJ, Jin J, Nan QY, Ding J, Cui S, Xuan MY. Coenzyme Q10 attenuates renal fibrosis by inhibiting RIP1-RIP3-MLKL-mediated necroinflammation via Wnt3α/β-catenin/GSK-3β signaling in unilateral ureteral obstruction. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;108:108868. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108868, PMID 35636077.

Nawaz S, Chinnadurai R, Al Chalabi S, Evans P, Kalra PA, Syed AA. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: a current review. Obes Sci Pract. 2023;9(2):61-74. doi: 10.1002/osp4.629, PMID 37034567.

Rojas Canales DM, Li JY, Makuei L, Gleadle JM. Compensatory renal hypertrophy following nephrectomy: when and how. Nephrology (Carlton). 2019;24(12):1225-32. doi: 10.1111/nep.13578, PMID 30809888.

Shen R, Xu F, Liu L, Mao H, Ren J. Unilateral ureteral obstruction model for investigating kidney interstitial fibrosis. J Vis Exp. 2025;(218):e67897. doi: 10.3791/67897, PMID 40354230.

Hammad FT. The long-term renal effects of short periods of unilateral ureteral obstruction. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2022;14(2):60-72. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1163-2, PMID 35619661.

Arifianto D, Adji D, Sutrisno B, Rickiawan N. Renal histopathology blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels of rats with unilateral ureteral obstruction. IJVS. 2020;1(1):1-9. doi: 10.22146/ijvs.v1i1.55183.

Arifianto B, Rickyawan D. Interplay of renal histopathology blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels in rats with unilateral ureteral obstruction: a comprehensive analysis. The American Journal of Veterinary Sciences and Wildlife Discovery. 2024;6(1):10-4. doi: 10.37547/tajvswd/Volume06Issue01-03.

Bulow RD, Boor P. Extracellular matrix in kidney fibrosis: more than just a scaffold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2019;67(9):643-61. doi: 10.1369/0022155419849388, PMID 31116062.

Schnaper HW. The tubulointerstitial pathophysiology of progressive kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(2):107-16. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.11.011, PMID 28284376.

Yakupova EI, Abramicheva PA, Bocharnikov AD, Andrianova NV, Plotnikov EY. Biomarkers of the end stage renal disease progression: beyond the GFR. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2023;88(10):1622-44. doi: 10.1134/S0006297923100164, PMID 38105029.

Chevalier RL, Forbes MS, Thornhill BA. Ureteral obstruction as a model of renal interstitial fibrosis and obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;75(11):1145-52. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.86, PMID 19340094.

Martinez Klimova E, Aparicio Trejo OE, Tapia E, Pedraza Chaverri J. Unilateral ureteral obstruction as a model to investigate fibrosis attenuating treatments. Biomolecules. 2019;9(4):141. doi: 10.3390/biom9040141, PMID 30965656.

Hijmans RS, Rasmussen DG, Yazdani S, Navis G, Van Goor H, Karsdal MA. Urinary collagen degradation products as early markers of progressive renal fibrosis. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1163-2, PMID 28320405.

La Russa A, Serra R, Faga T, Crugliano G, Bonelli A, Coppolino G. Kidney fibrosis and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2024;29(5):192. doi: 10.31083/j.fbl2905192, PMID 38812325.

Uddin MJ, Kim EH, Hannan MA, Ha H. Pharmacotherapy against oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease: promising small molecule natural products targeting nrf2-ho-1 signaling. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(2):258. doi: 10.3390/antiox10020258, PMID 33562389.

Grande MT, Lopez Novoa JM. Fibroblast activation and myofibroblast generation in obstructive nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(6):319-28. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.74, PMID 19474827.