Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 11, 10-14Review Article

A CLINICAL OVERVIEW ON URINARY TRACT INFECTION: RISK FACTORS, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT APPROACHES

VANKODOTH SIREESHA1, GANDLA KUMARA SWAMY2*

1Department of Pharmacy Practice, Chaitanya (Deemed to be University), Gandipet, Himayathnagar (vil), Hyderabad-500075, Telangana, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutical sciences, Chaitanya (Deemed to be University), Gandipet, Himayathnagar (vil), Hyderabad 500075, Telangana, India

*Corresponding author: Gandla Kumara Swamy; *Email: drkumaraswamygandla@gmail.com

Received: 14 Jul 2025, Revised and Accepted: 02 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) refer to the colonization and infection of the urinary tract by microorganisms. It is one of the most prevalent infectious diseases in hospitals and the general population, with nearly 10% of individuals suffering from UTI at some point in their lives. UTIs are most common in people between the ages of 16 and 64, and 50% of women worldwide are predicted to get them at least once in their lives. Gram-negative bacteria (GNBs) account for over 95% of all UTIs, with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Proteus, Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, and others being the most common causative agents for UTIs. Since bacteria are the primary cause of UTIs, the increase in antibiotic resistance, particularly multidrug-resistant (MDR) uropathogens, poses significant challenges to treatment. Treatment of MDR UTIs requires careful selection of antibiotics, with options like fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and fluoroquinolones, which are commonly employed. This review examines the risk factors, pathophysiology, management, and current treatment options for UTIs and MDR UTIs, highlighting the global impact of antibiotic resistance and the urgent need for effective management strategies to combat this growing public health concern. Clinicians have limited access to effective antibiotic treatments for treating these illnesses. Early detection and adequate empirical therapy are crucial steps in controlling these organisms, since they have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Urological, Multidrug resistance, Antibiotic resistance, Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, Urethritis, Microbiome uncomplicated

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i11.57197 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, urinary tract infections (UTIs) remain one of the most common infectious diseases encountered in both community and healthcare settings, affecting millions of people annually and posing a substantial public-health burden [1]. Urinary tract infections primarily arise from structural abnormalities of the urinary tract and functional disorders, such as inadequate bladder emptying. Men, women, children, and older adults can all be afflicted by these illnesses; however, the prevalence, clinical course, and risk factors frequently differ by sex and age [2].

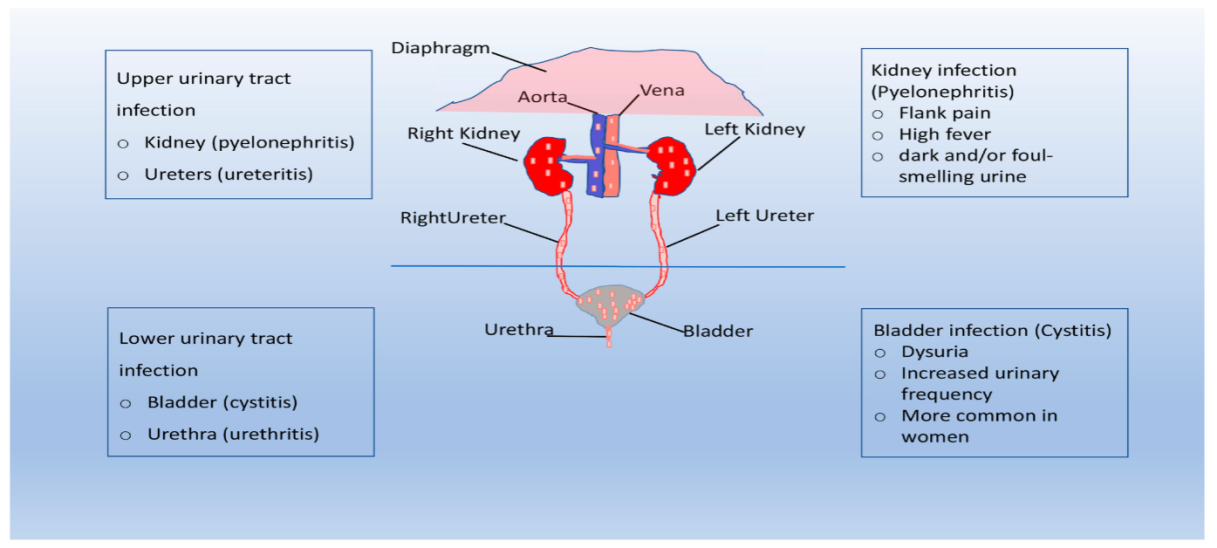

The term urinary tract infection refers to the colonization and infection of urinary tract structures by microorganisms [3]. Infection occurs when bacteria, often originating from the bowel or external environment, enter the urethra and ascend into the urinary tract. The urethra serves as both an opening for urine flow and a potential entry point for bacteria. Typically, urination flushes out these bacteria before they can reach deeper urinary structures. However, if bacteria successfully reach the bladder and evade elimination, colonization and infection develop. Anatomical factors, particularly in women due to a shorter urethra and its proximity to the rectum and vagina, make it easier for bacteria to enter the bladder before being removed by urination. This largely explains why urinary tract infections are more frequent in women than in men [2]. Additional influences include hormonal and microbiome factors [4]. UTIs are divided into three categories: Urethritis (urethral infection), Cystitis (urinary bladder infection), and Pyelonephritis (renal infection). They can be characterized as simple or complex and categorized as uncomplicated or complicated for treatment purposes [3]. An estimated 150 million people are impacted annually, with a yearly incidence of 3% for males and 12.6% for women. Germs that cause common diseases are increasing their resistance to antibiotics globally. Most UTIs can be treated effectively with medication, though recurrent and occasionally severe infections may occur [5].

Etiology

Urinary tract infections are caused mainly by bacteria, with current evaluations estimating that 90–95% of UTIs are caused by bacteria; however, fungi and sometimes some viruses have also been known to cause UTIs [6]. The germs that cause more than 85% of UTIs come from the vagina or gut. Rectal and perineal bacteria colonizing the urogenital tract are the main cause of almost all UTIs. The majority of UTIs are caused by Gram-negative bacteria, with the most common organisms being Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and other Enterococcus or Staphylococcus species. Simple cystitis and pyelonephritis are primarily caused by Escherichia coli, followed by other Enterobacteriaceae species, such as Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Gram-positive pathogens such as Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Enterococcus faecalis [7], and a few simple UTIs are caused by blood-borne bacteria. The most common causes of uncomplicated UTIs are E. Coli and potentially Klebsiella. A greater variety of organisms are typically responsible for complicated UTIs, which is important because certain antibiotic regimens differ due to the rise in multidrug resistance [8].

Clinical manifestations

UTIs often have no symptoms. When present, symptoms may include a strong urge to urinate, burning during urination, frequent small urinations, cloudy or strong-smelling urine, and sometimes blood-tinged urine. Women may feel pelvic discomfort [9].

Risk factors

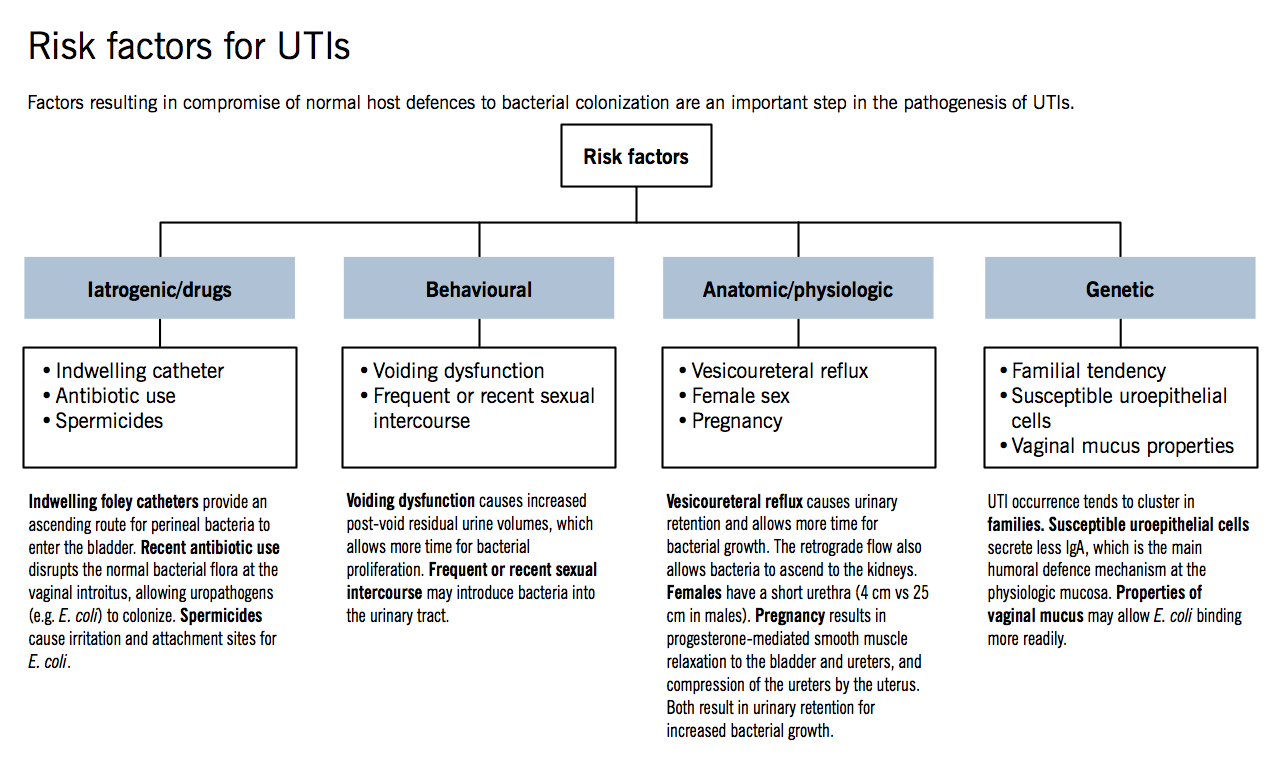

The various clinical conditions that accompany UTIs vary in their severity and place of origin. The risk of UTI is influenced by a wide range of intrinsic and acquired factors such as female sex, vesicoureteral reflux, frequent sexual activity, enlarged prostate gland, urine retention, family history, spermicide use, vaginal infection, obesity, and vulvovaginal atrophy [10, 11]. Patients with diabetes, indwelling catheters, immunocompromised individuals, those receiving residential care, and patients who are immobile due to medical restrictions, such as stroke, may also colonize with Bacteria and Candida [12]. Recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs) in women are influenced by an interplay of anatomical, hormonal, genetic, behavioral, and structural factors, which were explained in fig. 1. In postmenopausal women, estrogen deficiency thins the vaginal and urinary epithelium, diminishes protective lactobacilli, and compromises local immune barriers, thereby increasing susceptibility to rUTIs, they are also linked to incontinence, cystocele postvoidal residual urine 13, 14].

Behavioural factors

The biggest factors that contribute to women's recurrent UTIs are behavioural variables. The frequency of sexual activity is one such behaviour that makes UTIs more likely to recur in young women. The usage of spermicides and other forms of contraception, as well as other post-intercourse behaviours, are important contributors to UTIs. Even inappropriate use of tampons, menstrual hygiene, underwear material, and perineal washing practices all raise the chance of developing UTIs [15]. Previous use of antibiotics within the last three months was a significant independent predictor of resistant infections among risk factors for drug-resistant UTIs (community-acquired or hospital-acquired), along with diabetes mellitus, older age, and recurrent UTIs [16].

Genetic factors

Genetic factors linked to a higher risk of UTIs include polymorphisms in innate immune system-related genes, such as TLR4, CXCR1, CXCR2, TGF-β, and VEGF. These genes can influence the body's response to bacterial invasion in the urinary tract, and changes in these genes can result in a compromised immune response, which increases the risk of UTIs [17].

Age and gender

People of every age group are affected by UTIs, and they become more common in both sexes as they become older. The incidence of UTIs declines in middle age but then rises again in older persons. Women are more prone than men to lower UTIs due to the short urethra and the urethral openings near proximity to the anus and vagina, which are believed to be bacterial reservoirs [18]. The biggest risk factor for postmenopausal women is estrogen insufficiency [19]. Estrogen deficiency, especially postmenopausal levels, is linked to reduced bladder epithelial proliferation, diminished antimicrobial peptides, and vaginal mucosal atrophy, including fewer lactobacilli and higher pH, all of which elevate the risk of UPEC colonization [20].

Pregnancy-related factors

Urinary tract infections are independently related to pregnancy. Notably, both pregnant and non-pregnant women of reproductive age have an identical likelihood of developing UTI [21]. In pregnant women, streptococcus bacteriuria is a sign of colonization of the vaginal tract result in UTIs at serious risk. Pregnancy-related UTIs have also been linked to older age, a woman's lower socioeconomic status, Urinary tract anatomical anomalies, diabetes, and sickle cell disease [22].

Catheterization

There is a strong correlation between the length of catheterization and biofilm formation underscores the increased risk of UTIs and bacteriuria with prolonged catheter use [23].

Fig. 1: Risk factors for UTIs

Pathophysiology

Worldwide, the most common hospital-acquired infection and the most common bacterial infection in humans are urinary tract infections [24]. UTIs begin when uropathogens that survive in the gut and invade the urethra and subsequently the bladder by using certain adhesions, as shown in fig. 2 [25]. The bacteria begin to proliferate and create toxins and enzymes that can help in their survival if the host's inflammatory response is unable to completely eliminate them. If the pathogens are able to pass through the kidney epithelial barrier, bladder compromise follows infection by uropathogens, which happens with catheterization. A common occurrence is the accumulation of fibrinogen on the catheter as a result of the potent immunological reaction that is induced by catheterization. On expressing fibrinogen-binding proteins, uropathogens attach themselves to the catheter. Additionally, bacteria multiply because of biofilm protection, and if the infection is ignored, it may develop into bacteraemia and pyelonephritis. Uropathogens have developed a variety of techniques to cling to and penetrate the tissue of the host, and their efficiency is intimately linked to the expansion of UTIs [26]. In the early stages, the infection might not seem worrisome, but it could go considerably worse if there are aggravating factors [27, 28]. The development of UTI is complicated by biofilms, catheters, and urinary stasis brought on by blockage.

Diagnosis

In order to identify UTI, the following symptoms must be present such as dysuria, frequency, or urgency i) Analysis of urine: pyuria+bacteriuria±hematuria±nitrites ii) urine culture (straight-cath or clean-catch midstream), and iii) if: at least 103 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml for men, and at least 105 CFU/ml for women. There are several techniques for detecting UTIs, including phenotypical biochemistry and culture identification strategies, which are regarded to be slow due to the length of time it takes for bacteria to grow. There are also quick methods like PCR and immunoassay, with some drawbacks such as sensitivity, antigen concentrations, and seroconversion time. The gold standard technique is quantitative urine culture; however, it requires about 24 h to get results, and an additional 24 h are required for testing for antibiotic resistance. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy is the most recent way for detecting UTIs. This is a rapid diagnostic method that uses the spectra of bacterial strains found in urine samples [29]. A complete urine examination is an important step in diagnosing urinary tract infections (UTIs). Dipstick tests such as Multistix provide quick results by detecting leukocyte esterase, nitrite, blood, and protein. While dipsticks are useful for rapid screening, their accuracy varies, and urine culture remains the gold standard for confirmation. In case of recurrent UTIs, Ultrasound and CT scan are used to examine the kidneys and bladder for any abnormalities [30].

Fig. 2: Shows the colonization of bacteria in UTIs

Treatment

The Antibiotics that are used to treat urinary tract infections are fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides. Amoxicillin/clavulanate, Cefixime, Cefprozil, levofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, and nalidixic acid are other commonly used antibiotics for bacterial UTIs. The rate of morbidity and mortality from bacterial infections has dropped since the introduction of antibiotics. However, these uropathogens have become more resistant to antibiotics in recent years. Amoxicillin was once used as a first-line treatment for UTIs; however, it is no longer advised because of the increasing prevalence of E. coli resistance. Fluoroquinolones, Cephalosporins, and Aminoglycosides were found to have the highest resistance rates among uropathogens [31]. However, research has identified trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as an antibiotic with greater cure rates. Understanding the mode of action of antibiotics is necessary to create effective treatment [32]. Antibacterial agents eliminate or inhibit bacteria through distinct mechanisms: β-lactams (e. g., ampicillin, amoxiclav) disrupt peptidoglycan cross-linking, compromising cell wall integrity; fluoroquinolones impede DNA replication by targeting DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV; aminoglycosides selectively bind the 30S ribosomal subunit, causing mistranslation and defective proteins; while co-trimoxazole interrupts folate synthesis by dual inhibition of dihydropteroate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase, blocking critical nucleotide and amino acid production for bacterial growth [33].

E. Coli is the primary cause of uncomplicated UTIs, although multi-resistant uropathogens are more common in complicated UTIs, which have a wider range of bacteria. Conversely, uncomplicated UTIs also show rising rates of resistance, such as to co-trimoxazole, amino pencillins, and fluoroquinolones. The empirical treatment must take this fact into account.

Table 1 shows the aetiology, clinical presentations, treatment options, and management of UTI based on the type of infection.

Table 1: Treatment for UTI based on the type of infection

| Type of infection | Symptoms | Treatment |

Uncomplicated cystitis Common organisms: E. coli Other organisms: Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella, pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus. |

|

1st line

2ndline

|

Complicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis Common organisms: E. Coli Other Organisms: Proteus spp.,Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

|

1st line**

|

*Avoid nitrofurantoin if early pyelonephritis is suspected. Avoid if CrCl<30 ml/min OR in patients older than 65 due to renal clearance. ** If local E. coli resistance exceeds 10%, ceftriaxone 1g IM should be used (1 dose) prior to initiating oral therapy [34].

Treatment for recurrent urinary tract infection

Recurrent urinary tract infections (RUTIs), commonly affecting younger sexually active and post-menopausal women, are managed by distinguishing between infrequent episodes (fewer than two to three per year) and frequent recurrences (more than three per year). Infrequent episodes are treated acutely as separate infections. For frequent RUTIs, after considering risks and benefits, long-term prophylaxis is an effective strategy for recurrence prevention, using agents such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, or cephalosporins (e.g., cephalexin), typically for 6–12 mo. Intermittent (e.g., post-coital) prophylaxis or continuous low-dose regimens can be similarly effective. At any time during prophylaxis, symptomatic breakthrough infections should be treated with a full therapeutic antibiotic course [35].

A urine culture with ≥105 colony-forming units/ml and no specific UTI symptoms is known as asymptomatic bacteriuria, as it usually resolves on its own without treatment [36]. As antibiotic treatment may contribute to the development of bacterial resistance, asymptomatic UTIs should only be treated in specific cases, such as pregnant women, neutropenic patients, and those undergoing genitourinary surgery. Symptomatic UTIs, however, are often treated with antibiotics, which might alter intestinal and vaginal microbiota and increase the risk factors for drug-resistant bacteria proliferating [37].

Novel antibiotics for multidrug-resistant (MDR) urinary tract infection (UTI)

Symptomatic UTI patients are usually treated with antibiotics, which can result in the formation of multidrug-resistant microorganisms and a long-term change in the normal vaginal and gastrointestinal tract microbiota. UTIs are a leading cause of sepsis and bacteremia in older adults and frequently result in hospitalization for infection. The enzymes known as extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), which are commonly responsible for UTIs, are produced by Escherichia coli and other bacteria. Simultaneous antibiotic resistance is common because the same plasmids that carry ESBL genes often encode resistance to multiple antibiotics. As a result, multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms are increasingly responsible for UTIs, increasing the chances of treatment failure in both community-acquired and healthcare-associated illnesses [38]. Recent advances in antibiotic development have expanded options for treating complicated and multidrug-resistant urinary tract infections (UTIs). Novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations such as cefepime–zidebactam, cefepime–enmetazobactam, ceftazidime–avibactam, and cefepime–taniborbactam show strong activity against resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Cefiderocol, a siderophore cephalosporin, has proven effective in Phase III trials, while pivmecillinam has recently been FDA-approved as an oral agent for uncomplicated UTIs. Gepotidacin, another newly approved oral drug, offers a novel dual-target mechanism against bacterial DNA replication. Traditional agents like nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole remain effective for uncomplicated cases, while fosfomycin continues to be useful in recurrent and resistant infections [39].

Prevention of UTIs

Lifestyle modifications play a crucial role in preventing and managing UTIs. Dietary changes such as staying hydrated, urinating when needed, and avoiding sugary and acidic foods can help prevent UTIs. Practicing good hygiene, exercising regularly, and managing stress may also decrease the risk of getting a UTI. Additionally, increasing cranberry consumption has been shown to be beneficial in preventing UTIs. By incorporating these lifestyle modifications, individuals can reduce their risk of developing UTIs and manage symptoms more effectively [40].

CONCLUSION

Urinary tract infections are prevalent and serious medical illness that impacts millions of people globally. The majority of UTIs are caused by Gram-negative bacteria, with Escherichia coli being the most common species. Understanding the risk factors, pathophysiology, and treatment options is crucial for effective management. A comprehensive approach, including accurate diagnosis, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and lifestyle modifications, can help prevent and treat UTIs. The vast variations in resistance patterns across different geographic locations and healthcare environments make empirical treatment techniques more challenging. Commonly used antibiotics like fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides have seen their effectiveness severely weakened by the emergence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), plasmid-mediated resistance, and other resistance mechanisms like decreased permeability and enzymatic inactivation. Ongoing research and advancements in pharmacogenomics and antimicrobial stewardship hold promise for improving UTI treatment outcomes.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Author 1 and 2 contributed equally to the conception. Author 1 and 3 contributed equally to the literature review and writing of the manuscript. Author 1 and 3 were responsible for the initial draft and author 1 and 2 revised and finalized the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version for submission.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Medina M, Castillo Pino E. An introduction to the epidemiology and burden of urinary tract infections. Ther Adv Urol. 2019;11:1756287219832172. doi: 10.1177/1756287219832172, PMID 31105774.

Mancuso G, Midiri A, Gerace E, Marra M, Zummo S, Biondo C. Urinary tract infections: the current scenario and future prospects. Pathogens. 2023;12(4):623. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12040623, PMID 37111509.

Patel HB, Soni ST, Bhagyalaxmi A, Patel NM. Causative agents of urinary tract infections and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns at a referral center in Western India: an audit to help clinicians prevent antibiotic misuse. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(1):154-9. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_203_18, PMID 30911498.

Sujith S, Solomon AP, Rayappan JB. Comprehensive insights into UTIs: from pathophysiology to precision diagnosis and management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1402941. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1402941, PMID 39380727.

Jhang JF, Kuo HC. Recent advances in recurrent urinary tract infection from pathogenesis and biomarkers to prevention. Tzu Chi Med J. 2017;29(3):131-7. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_53_17, PMID 28974905.

Flores Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(5):269-84. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432, PMID 25853778.

Mazzariol A, Bazaj A, Cornaglia G. Multi-drug-resistant gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections: a review. J Chemother. 2017;29Suppl1:2-9. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2017.1380395, PMID 29271736.

Bono MJ, Reygaert WC, Leslie SW. Urinary tract infection. In: Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Stat Pearls. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470195. [Last accessed on 01 Sep 2025].

Mayo Clinic. Urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic Publications; 2022. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/urinary-tract-infection/symptoms-causes/syc-20353447. [Last accessed on 01 Sep 2025].

Craven BC, Alavinia SM, Gajewski JB, Parmar R, Disher S, Ethans K. Conception and development of urinary tract infection indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-High Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42Suppl1:205-14. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2019.1647928, PMID 31573440.

Wiley Z, Jacob JT, Burd EM. Targeting asymptomatic bacteriuria in antimicrobial stewardship: the role of the microbiology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(5):e00518-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00518-18, PMID 32051261.

Sabih A, Leslie SW. Complicated urinary tract infections. In: Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. StatPearls. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436013. [Last accessed on 01 Sep 2025].

Brauner H, Parras C, Nyberg L. Overcoming challenges in the management of recurrent urinary tract infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;7(3):e00016-2019. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.BAI-0016-2019.

Huang ES, Halusha L, Shulruf I. Genetic predisposition and host defense deficiencies increase recurrent UTI risk in women. Eur Urol. 2022;60:181-94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.01.015.

Moore EE, Hawes SE, Scholes D, Boyko EJ, Hughes JP, Fihn SD. Sexual intercourse and risk of symptomatic urinary tract infection in post-menopausal women. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):595-9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0535-y, PMID 18266044.

Xu X, Huang P, Cui X, Li X, Sun J, Ji Q. Effects of dietary coated lysozyme on the growth performance antioxidant activity immunity and gut health of weaned piglets. Antibiotics. 2022;11(11):1470. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111470, PMID 36358125.

Godaly G, Ambite I, Svanborg C. Innate immunity and genetic determinants of urinary tract infection susceptibility. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000127, PMID 25539411.

Sujith S, Solomon AP, Rayappan JB. Comprehensive insights into UTIs: from pathophysiology to precision diagnosis and management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14(1):1402941. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1402941, PMID 39380727.

Aydin A, Ahmed K, Zaman I, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(6):795-804. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2569-5, PMID 25410372.

Engelsoy U, Svensson MA, Demirel I. Estradiol alters the virulence traits of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:682626. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.682626, PMID 34354683.

Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, Colgan R, De Muri GP, Drekonja D. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(10):e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121, PMID 30895288.

Matuszkiewicz Rowinska J, Malyszko J, Wieliczko M. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy: old and new unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic problems. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11(1):67-77. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.39202, PMID 25861291.

Gambrill B, Pertusati F, Hughes SF, Shergill I, Prokopovich P. Materials-based incidence of urinary catheter-associated urinary tract infections and the causative micro-organisms: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2024;24(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s12894-024-01565-x, PMID 39215290.

McLellan LK, Hunstad DA. Urinary tract infection: pathogenesis and outlook. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(11):946-57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.09.003, PMID 27692880.

Mancuso G, Midiri A, Gerace E, Marra M, Zummo S, Biondo C. Urinary tract infections: the current scenario and future prospects. Pathogens. 2023;12(4):623. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12040623, PMID 37111509.

Lewis AJ, Richards AC, Mulvey MA. Invasion of host cells and tissues by uropathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(6):359-81. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0026-2016, PMID 28087946.

Zagaglia C, Ammendolia MG, Maurizi L, Nicoletti M, Longhi C. Urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains-new strategies for an old pathogen. Microorganisms. 2022;10(7):1425. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071425, PMID 35889146.

Storme O, Tiran Saucedo J, Garcia Mora A, Dehesa Davila M, Naber KG. Risk factors and predisposing conditions for urinary tract infection. Ther Adv Urol. 2019;11:1756287218814382. doi: 10.1177/1756287218814382, PMID 31105772.

Premasiri WR, Chen Y, Williamson PM, Bandarage DC, Pyles C, Ziegler LD. Rapid urinary tract infection diagnostics by surface enhanced raman spectroscopy (SERS): identification and antibiotic susceptibilities. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(11):3043-54. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0244-7, PMID 28235996.

Gurung R, Adhikari S, Adhikari N, Sapkota S, Rana JC, Dhungel B. Efficacy of urine dipstick test in diagnosing urinary tract infection and detection of the blaCTX-M gene among ESBL-producing Escherichia coli. Diseases. 2021;9(3):59. doi: 10.3390/diseases9030059, PMID 34562966.

Li X, Fan H, Zi H, Hu H, Li B, Huang J. Global and regional burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in urinary tract infections in 2019. J Clin Med. 2022;11(10):2817. doi: 10.3390/jcm11102817, PMID 35628941.

Kaur R, Kaur R. Symptoms risk factors, diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1154):803-12. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139090, PMID 33234708.

Zheng P, Hu X, Wang L. Design and synthesis of novel antimicrobial agents. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1184502.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654, PMID 33433946.

Albert X, Huertas I, Pereiro II, Sanfelix J, Gosalbes V, Perrota C. Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2004(3):CD001209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001209.pub2, PMID 15266443.

Luu T, Albarillo FS. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: prevalence diagnosis, management and current antimicrobial stewardship implementations. Am J Med. 2022;135(8):e236-44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.03.015, PMID 35367448.

Mestrovic T, Matijasic M, Peric M, Cipcic Paljetak H, Baresic A, Verbanac D. The role of gut vaginal and urinary microbiome in urinary tract infections: from bench to bedside. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;11(1):7. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11010007, PMID 33375202.

Madrazo M, Esparcia A, Lopez Cruz I, Alberola J, Piles L, Viana A. Clinical impact of multidrug resistant bacteria in older hospitalized patients with community acquired urinary tract infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1232. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06939-2, PMID 34876045.

Rodriguez Bano J, Gutierrez Gutierrez B, Machuca I, Pascual A. Treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase Amp C and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31(2):e00079-17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00079-17, PMID 29444952.

Jangid H, Chauhan A, Sharma V, Singh S, Choudhary R. Cranberry-derived bioactives for the prevention and management of recurrent urinary tract infections. Front Nutr. 2025;8:1502720. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1502720.